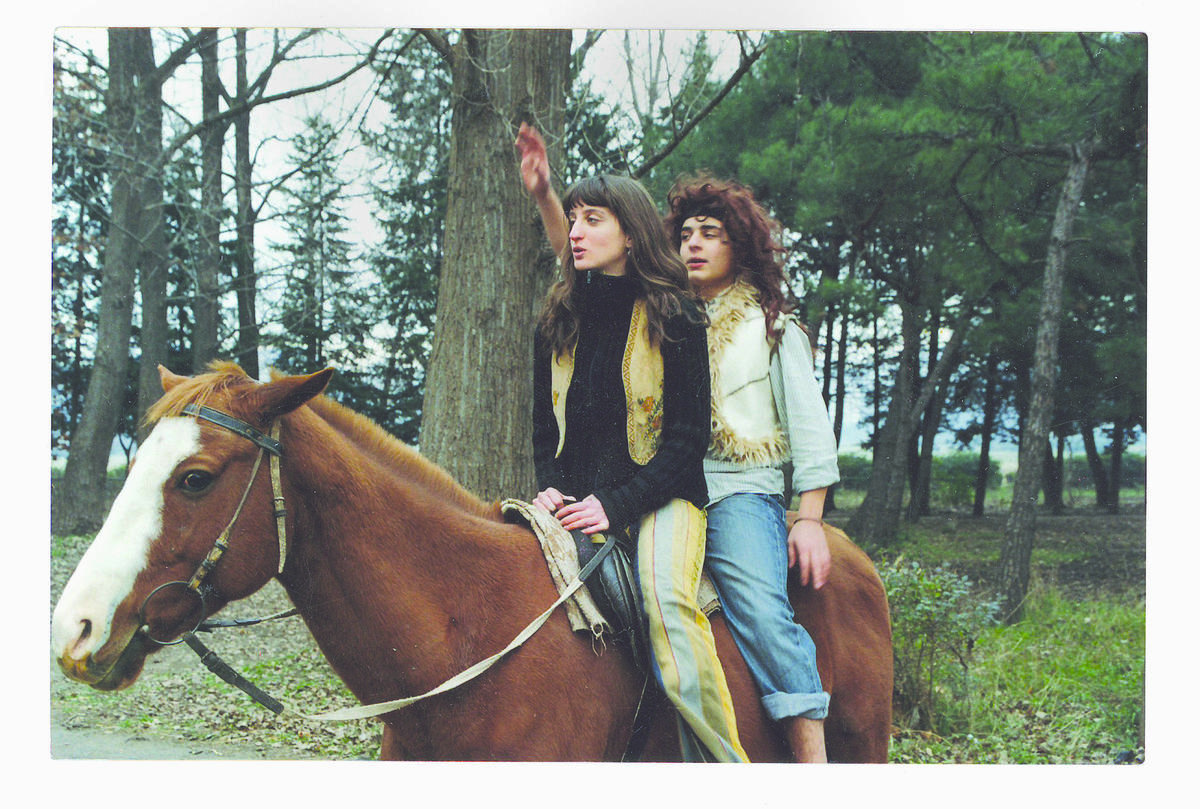

Anna and Lisa are identical twins; one is an art student, the other is studying to be a journalist. With friends they have started to re-make — frame by frame — the 1970’s cult American musical “Hair.” Here, they discuss hippiedom and the new free love in the post-Soviet Republic of Georgia with Bidoun.

Bidoun: Why did you choose this particular film? Do you sense that it’s relevant to cultural changes taking place in Georgia?

Anna: We had all watched the film numerous times from childhood on; for some reason it was always on television. Growing up, I had always loved it, but didn’t realize what it meant or symbolized. To me, these people were just having a really good time. Then two years ago it was on television again, and I realized how amazing it was that people lived like that, that their life didn’t solely revolve around going to university and then coming home. The next day my friends and I found a tape of the movie somewhere and watched it together over and over. It started to feel as if it was our experience, as if these people were our friends — it became our thing. You have to understand that here, there is nothing for kids our age to do but get married or get high.

Lisa: Then a friend, Ketevan, who studies in Paris, bought a book of the movie’s lyrics and dialogues, and we started memorizing it. The idea of a remake came about spontaneously. Most of us go to the Academy of Fine Arts and decided to fool around — get all our grandmother’s clothes out, put makeup on, lip-sync, and shoot. Then one of us started to learn an editing program. Although we work hard and are totally dedicated, the project is still informal .

Bidoun: A film production company offered to fund, distribute, and promote your project. Why did you refuse the help?

L: Because it’s not about any of that. It’s about having fun, about making the film the way that those characters live, about using whatever money we have in our pockets the day we shoot and not having anyone tell us what to do. Also, they assumed it was a parody, and offered to collaborate on a series of remakes. But our project is not a parody — we love Hair.

Bidoun: How many are you?

L: There are four or five main players, but about twenty or twentyfive people ended up being seduced by the project. They mostly heard about the shooting days and showed up in torn jeans, messy hair and so on because they knew they could get away with it on the shoot. When we first started the project, the number one question was whether any boys would get involved. Because most boys have so many complexes and are so restrained, we never thought we would find any who would be willing to dance around in wigs and think about the notion of freedom. But surprisingly we found a few boys who didn’t want to spend their lives playing with guns, showing off weird knife tricks, and looking for a fight.

Bidoun: The remake seems to have created a space where no rules apply and there are no repercussions. People can come to the shoot, go crazy, and go home safely. It makes me think of S&M clubs in the West.

A: Yes. Our parents and their friends have heard about the movie and like the idea of it — for some reason—so it’s less of a stigma.

L: The sole reason we do this stuff is to have a good time. There is nothing to do around here. Go to a café, have a coffee, smoke a cigarette — it’s so boring. We don’t go to clubs because I always feel tense that someone is going to offend someone and start a fight. We barely leave the house unless there is something really important going on, like a birthday or a funeral. We save our energy for the shoots and the summer rock festival.

Bidoun: Why don’t you go all the way and live like the hippies did back then?

A: Well, probably because we are not really as free as they were, and the time is completely different. Also, Georgians have so much ingrained respect for family. Once, as I watched Hair for the tenth time, I caught myself thinking, “Okay, it’s awesome that they wander around aimlessly all day, but don’t they want to go home and sit down for a minute? Go have tea with their grandmother?” We are all so busy with our lives. We don’t have much free time. They were protesting; what do we have to protest? We only want to say that we have no way to have a good time, and that’s why we do it: to be young and have fun. We have such a great laugh making our costumes, scouting locations, taking photographs, and discussing the results from the shoots.

L: Our goal is to make a tape of the finished version and distribute it all around the city, so that the very people that ridicule us can see how much fun we were having while they spent their time being cool or acting like gangsters.

Bidoun: During and after Perestroika, Hollywood gangster films such as Scarface or The Godfather were considered iconic in Georgia. These movies emblematized chaotic times in a way that Georgian youth really related to. It made sense for them to romanticize violence, wear black, make money illegally, and produce more violence. Now, instead of gelled hair and shiny black leather shoes, I see kids in colors and beads and Converse sneakers. It seems like what was going on in the West in the 1960s or the ’70s is happening here now, but in a much less radical manner. We don’t hold quite the same opinions of sexual liberation and drugs.

A: No, we are all for free love, but more in theory than in practice. As for drug use, you have to understand that drugs in our context mean heroin or subotex. And for us, it’s the lamest thing for a person to do. So, no, drugs don’t hold any prestige with us. It’s the other values, of love and friendship and comradeship, that attract us.