Dubai

Roads Were Open/Roads Were Closed: On How We Perceive Conflict

The Third Line

September 6–October 2, 2008

“Frankly, I don’t know why I’m in this show,” said Fouad Elkoury, at a panel discussion to launch Roads Were Open / Roads Were Closed: On How We Perceive Conflict. He had a playful glint in his eye as he spoke, but his comment nonetheless laid bare the fraught nature of such an unwieldy theme as “conflict.”

Of course, the artists in this show — Elkoury, Tarek Al Ghoussein, Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, and Laila Shawa — are presumably all too familiar with their work being positioned in relation to questions of war, particularly given the proliferation of international group shows on or about conflict in Lebanon and the wider Arab world (a recent example was the Centre Pompidou’s The Anxious). Plainly, curator Haig Aivazian had set himself a formidable task: to present this work in Dubai in all its complexity without reducing or creating an uncritical normalization of the theme.

Supplementing the exhibition with a film series (which included Hadjithomas and Joreige’s A Perfect Day, Annemarie Jacir’s like twenty impossibles, and Ghassan Salhab’s Beyrouth Fantome), as well as a series of talks, was one strategy. Aivazian crafted a space in which to ponder the multiple meanings that could be engendered by the rubric of conflict. In an accompanying essay, he described how the exhibition aimed to lend itself to a diversity of experiences, by setting out to examine the way cities at war become cities in flux and experiential in nature; the artists, he wrote, “look[ed] to address the politics of accumulation and distribution of information as well as the complexities of how we live and perceive trauma, and how we come to piece together our memories of it.”

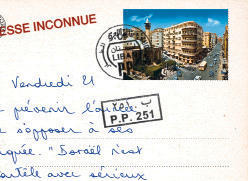

The exhibition went some way toward achieving its aims. Elkoury’s On War and Love, a daily diary set during the 2006 war in Lebanon, hung opposite Hadjithomas and Joreige’s Latent Images, a set of contact sheets that, instead of images, displayed precise photographer’s notes describing each image in rolls of undeveloped film. Latent Images was a part of the artists’ ongoing project Wonder Beirut, which includes a series of postcard images of the city, ostensibly taken before the civil war by the (fictional) photographer Abdallah Farah and gradually disfigured and burnt to reflect the mounting destruction of the city.

The contact sheets formed an intimate narrative arc. Covering the period 1997–2007, they took in national events (demonstrations, the 2006 war, the death of journalist Samir Kassir) as well as the purely personal. They were dryly melancholic and witty, relating the end of an affair through billboards advertising cheesy albums, for example. Wholly absorbing yet at the same time oblique, they seemed to propose a test of visual memory or imagined recall.

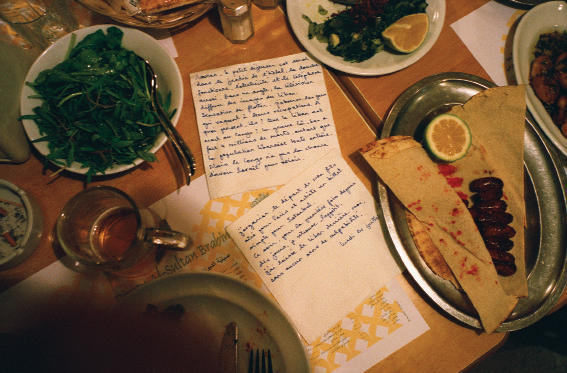

Elkoury’s diary was more personal and direct, albeit with the same mix of sadness and droll humor. Its images began in Beirut on July 13, the eve of war, and continued to Amman and then Istanbul, where Elkoury met his girlfriend. Gradually his doomed relationship appeared to subsume the daily goings-on of the war. Each entry was written on a photograph or series of images, occasionally as a caption but more often on the images themselves, following the line of a bombed bridge, a bare arm, a window, and the icing on a cake, for example. Together they formed a meticulous yet playful storyboard, intimate and full of pain, yet never mawkish.

While in previous work Elkoury had set stills to film (in Letters to Francine, for example), here he reversed the process. The artist worked as a documentary photographer during and after the civil war, and it was tempting to see this work as the end of an affair with Lebanon as well as with Elkoury’s girlfriend. But the glibness of that reading would have obscured the work’s play on narrative, hindsight, and the layering of perception and memory.

Elkoury appeared to rely as much for news of the war on dinner party discussion and taxi drivers’ opinions; Hadjithomas and Joreige’s photographer documented events but wove in minute observations and his own personal narrative.

Tarek Al Ghoussein’s large-format photographs of walls, taken in the UAE, implicitly referred to his Palestinian background and the Wall. The images were explicitly constructed and performed and exactingly composed and printed. He built tension by focusing on his subject — the finality of the concrete, the heaviness of the barrier — and then dragging attention away from it, by studying the detritus of construction in the foreground or positioning himself alongside or between the walls.

For the most part, the exhibition succeeded in walking the familiar high wire, but there were occasional tumbles. In addition to three images from Ghoussein’s B Series (of walls) was one from the A Series, with the artist wearing a kaffiyeh next to some industrial gravel pits; it jarred in this context. Likewise jarring was Laila Shawa’s one-liner, Weapons of Mass Destruction (2002), an oversize slingshot of a wooden branch and taut industrial elastic, about to ping a boulder.

Roads Were Open was the kind of inquiry that would be ambitious in a museum, let alone in a commercial gallery. In the absence of any public arts buildings in Dubai, galleries like Third Line attempt to fill the discursive gap with organized debates, reading clubs, and film nights. Curators willing to engage with difficult themes — curators in general — are few and far between, and their determination should be lauded.