The artist Rokni Haerizadeh has been known to depict weddings, funerals, banquets, and beheadings. The setting for these often overly elaborate and coded ceremonies has been, variously, decadent and corrupt nineteenth-century Iran, the dingy margins of the contemporary European city, or even the glittering metropolis of Dubai, where Haerizadeh has made his home since 2009.

For his latest project, the thirty-three-year-old artist turns his attentions to the pomp and gaudy gaiety of last spring’s British royal wedding, starring Prince William and his pretty field hockey-playing bride, Kate Middleton. Despite the royal family’s best attempts to suggest the event would be a democratic affair (they declared it the “people’s wedding” and invited some homeless people, too) the ceremony was, of course, a spectacle that brought the country to a screeching halt as millions turned to their televisions to witness the rich in their pyramids take part in an elaborately arcane, if not outright feudal tradition.

Haerizadeh, whose last animation work took as its subject another televised affair, the Iranian street demonstrations of 2009, filmed the wedding, all three hours of it, at home. After editing the already pixelated royal footage to a cut of roughly ten minutes, Haerizadeh broke up the ten minutes into thousands of frames (twelve thousand to be precise), printed each frame on A4 paper, and marked the surfaces with gesso, watercolor, and ink. When the sheets are all sewn together, the work will represent an unlikely, if not maudlin, take on this exploding piñata of privilege.

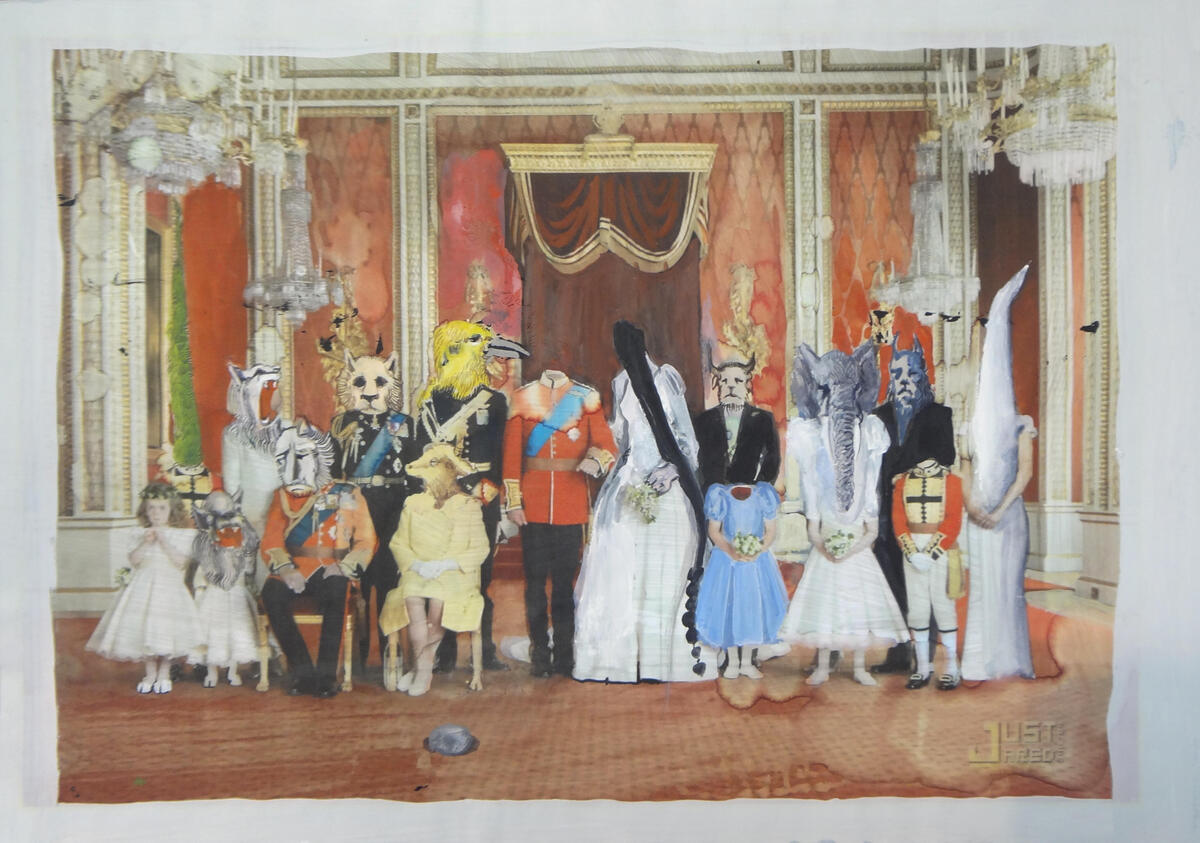

In one still from this work in progress, we see the familiar image of Mr. Middleton escorting his daughter in a grand procession. Her head is all but absent (so is his), and from her neck’s empty socket trails a set of little black balls that look like sex toys. The train of her bridal gown has morphed into an oversize human ear; and, from either side, what appears to be a river of blood emerges. In another still, a presiding priest’s entire face is absent, and has been replaced by a set of garish gaping jaws. Guards mounted atop horses are rendered as menacing centaurs. A state portrait of the royal family brings together a sad elephant, a horse, a toucan, a lion, and, of course, another headless apparition. That Mohammad-Reza Shajarian’s melancholy song “The Reign of Winter” — which narrates a man walking alone through the dead night of winter — is playing softly throughout, only adds to the creepy dissonance of what would otherwise be a carnival of good vibes.

This is not the first time that Haerizadeh has used animals in his work, as the anthropomorphic mode is a common one in many of his studies of human behavior — situations he sometimes refers to as “urban fairytales.” In Fictionville, exhibited at the Sharjah Biennial in 2011, televised images of heroic Iranian protests were modified to depict gazelles, giraffes, and other animals running hysterically through Tehran streets. Riot police were rendered as demons. Protesters were hapless clowns. The work’s title riffed on a storied Iranian avant-garde play written during the rule of the Shah, Shahre Ghese (or “City of Tales”), in which an allegorical animal land serves as a stand-in for some of the more trenchant political realities of the day.

Of course, you might say that Haerizadeh is interested in revisiting some of the more iconic moments of recent history. This is true. And yet still, these are intimate, absurd, and completely alternative readings of these histories. Psychological portraits are privileged over sweeping, official narratives. The trumpeter, the second cousin twice-removed, the accidental bystander — the real story resides in each of them. In this way, it is not entirely surprising that the artist was close to the late Iranian modernist sculptor Bahman Mohasses, who was similarly invested in the queer interior lives of people on the margins.

In conversation about the piece, Haerizadeh turns, somewhat surprisingly, to the storied Crystal Palace — erected to house marvels of the Industrial Revolution in London’s Hyde Park for the Great Exhibition of 1851. Assembled within the Palace’s bounds were endless markers of progress and travel: daguerreotypes, stereoscopes, a miniature scale model of New York City, a polar bear, dozens of dioramas, and all manner of manufacturing eclectica. Built improbably with endless sheets of glass and iron, the palace was hailed many times over as the very first manifestation of modern architecture in the world. Its blazing collapse some eighty-five years later, in 1936, marked a dramatic end to a structure that consolidated within its bounds the history of the British empire, the birth of global commercial culture, and the curious arc of bloated national aspirations.

Not unlike the shimmering Crystal Palace, the royal wedding shines like a beacon to the world, communicating, at best, history, sophistication, and tradition. Its choreography is a sort of architecture in and of itself, providing the scaffolding for the dissemination of beloved and berated national myths. And while it has not yet burned to the ground, Haerizadeh’s darkly comic and absurdly pixelated animation seems to point to a day in which yet another peculiar ritual might just crack into a million tragic pieces.