It seems that “unconventional” hairstyles are this season’s taboo in the Islamic Republic. “Football clubs have been ordered to stop players with long, messy hair, ponytails, hair bands and certain kinds of beard, or they will be fined and banned from playing,” warned Iran’s Football Federation in November.

Unconventional beards reference a host of Iranian variations on the goatee (bozi). The professori, the thicker traditional version and the diplomat, a sculpted matrix of thin lines from lip to chin, are both under fire: last year the Tehran passport office stopped accepting either, demanding either a full beard or no beard at all in official pictures. Photo studios opposite the office digitally erase offending beardlets on request, producing computer images which the authorities then accept. Less inventive travelers head, glassy eyed, for the barber downstairs. Goatees have also become the bête noire in official advertising. A new cartoon advert on Tehran’s highways warns of the dangers of driving and mobile phones. It sketches a fast-living young gun wearing the shades and studied diplomat of North Tehran coffeeshop cruisers: he shouts into his mobile as he ploughs into an angelic, veiled, young girl.

But despite being unorthodox, renegade beardlets now outnumber the beard on Tehran’s streets and new regulations are unlikely to have much affect. Recent restrictions are testimony to a conservative attempt to shore up revolutionary self-presentation, long on the defensive. In 1979, the full beard became the flag-bearing reversal of the smooth-cheeked pahlavi model and Ayatollah Khomeini himself underlined Islamic fiqh against shaving. But after less than a decade of pre-eminence, the beard’s crown began to slip, and creative razor work has been undermining its position ever since.

The Pahlavi era was marked by a clean-cut reorientation westwards, sandwiched between two eras of hairier clerical influence. Reza Shah banned chadors in 1936 and endorsed shaving in his drive to “modernize” Iran, dragging his country towards Europe and brow beating it into gender desegregation. Until then, smooth cheeks had been a passing stage, the ephemeral beauty of the ghilman, heaven’s lithe cupbearer, on the road to clerically mandated, bearded adulthood. Amongst the elite, the tide had been flowing towards the European prettyboy since the turn of the century, but with Reza Shah’s injunction the Iranian male lost a potent emblem of manhood, and the mustache drooped under the pressure to fulfill the beard’s former role.

Though today a dying breed among Iran’s youth, for the older generation and in northwest Iran, mustaches have maintained their past significance. “By the hair of my mustache” remains a binding pledge for Kurds and Lors. A Qomi Ayatollah was handed a hair from a Kurd’s mustache, carefully plucked and filed in a plastic wallet, as surety for a loan of 50,000 Tuman ($44). A year later the Kurd returned with the money, to the Ayatollah’s surprise and pleasure. His smile faded, however, when the Kurd adamantly demanded the return of his hair. A panicked rummage through drawers and cupboards finally yielded the item, and the Kurd departed, his honor satisfied.

The Islamic Revolution tipped the balance back in favor of the beard. A bushy beard bore the double hallmarks of Islam and the Red Revolutionary. Fidel Castro, whose own beard has for so long been the object of tragic-comic CIA machinations — exploding cigars and depilatory dust attacks top the list of intrigues — became a favorite of the new establishment. But aside from its philosophical symbolism, beards soon signaled adherence to the new regime, and became an employment and university prerequisite. Iranian Communists maintained their uniform of short hair, thick mustaches and spectacles for the first few years of the revolution. But by 1981 their tokens were fading, sinking into the sea of conformist beards as they came under attack.

Wall paintings are odes to the beard’s glory days. Memorials to martyrs throughout Iranian cities almost exclusively feature men with beards or at least a heavy tah-rish, the revolutionary stubble that is still favored by soldiers and intelligence agents, most often meticulously painted a moldy green in murals. The unbearded portrait signals youth, full growth denied by death. The beardless martyr sacrifices his manhood for the revolution, and the celestial lights, fields of flowers, beckoning sunsets, invoke once again the ghilman.

But from the end of the Iran-Iraq war in 1988, beards of ordinary Iranians started thinning. In 1997, President Mohammad Khatami’s suave beard and pressed clothes accompanied an easing of social regulations and altered “the rougher the better” principle that had lived on in establishment corridors. It was the beginning of the end. Clerics trimmed their manes, and stubble started fading from government ministries. For the first time, long-haired boys found themselves un-harassed in universities. Today, dread locks remain a pipe dream but on the streets of the capital, but shaved patterns of the hip-hop generation are taking their tentative first steps.

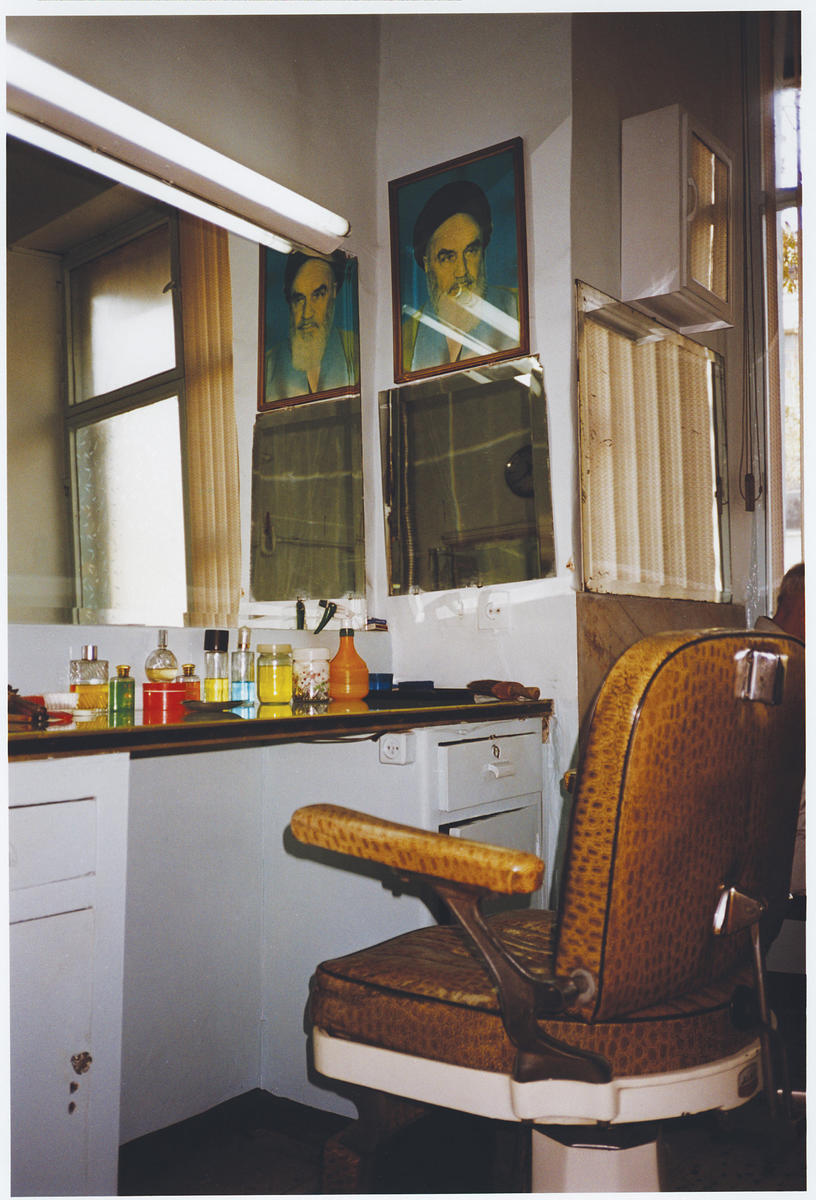

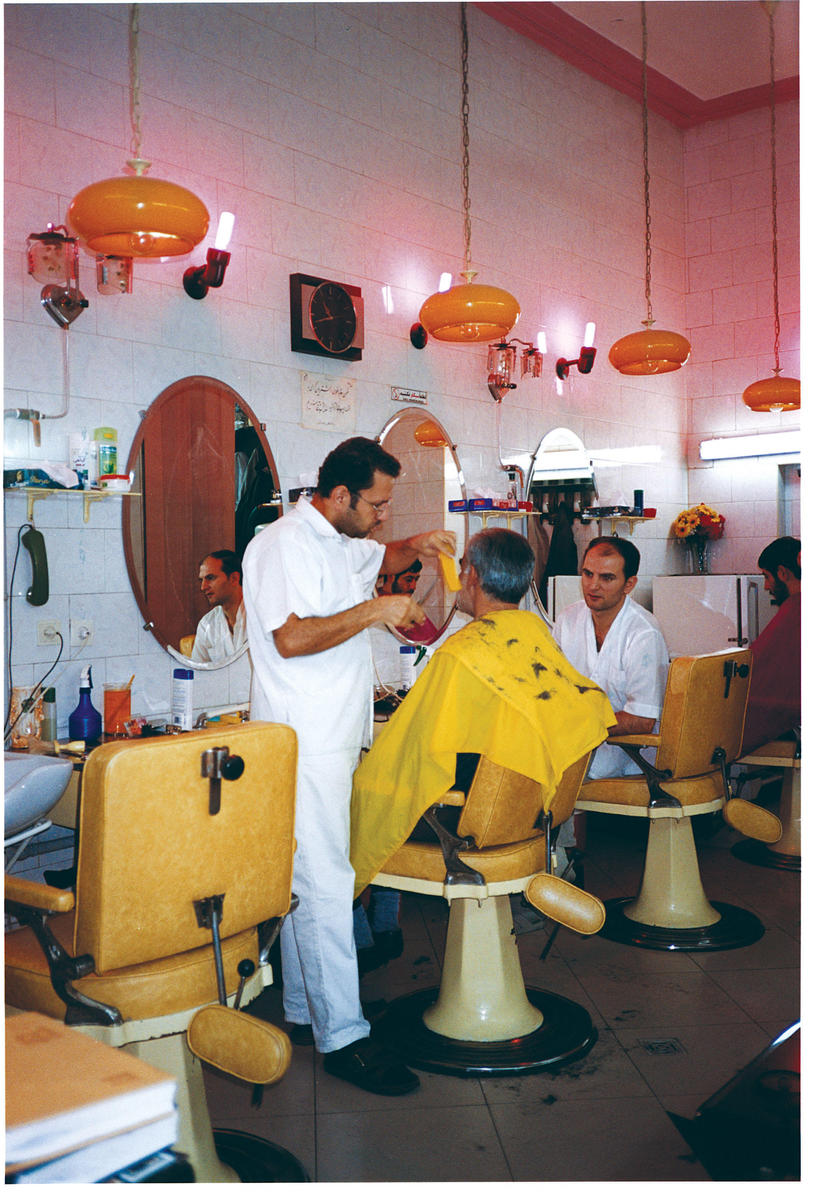

Ahmad, proprietor of Mootah, “Tehran’s best barber,” pioneers these new styles. His salon is tucked away upstairs from a quiet mall near Shariati, a major Tehran boulevard. High maintenance males bask in the warmth of hair dryers, admire their highlights and pat down implants on leather padded swivel chairs. Foreign styles have long influenced Iranian barber techniques, and satellite-beamed international football is today’s strongest influence. Ahmad charted the history of “the West” on Iranian hair for me one day, from Elvis and the Beatles to “the Beckam” and the “del Piero.” My name, Cornelie, it turns out, is the Iranian version of John Travolta’s Grease bonce, a dinosaur still lurking in “the provinces.” While the Duran Duran posht boland (mullet) lingers on it’s the plain, shaved staple of western offices that’s gaining ground.

And today, as the razor calls siren-like even to news readers and policemen, the beard is scrabbling for a role within the official message of the establishment. While a bearded renaissance, has been gaining ground on the margins for the past few years among artists, poets and musicians, the style is an emblematic world away from its revolutionary counterpart. Their long beards, long hair and long mustaches have a separate history, rooted in both the Sufi Dervish and the hippy in an ironic to-and-fro of East and West. In a twist of fate, this style was in fashion in the late seventh and eighth century: it announced opposition to laws laid down by Arab invaders bringing Islam and shaved upper lips to the land of the Aryans. The revolutionary beard, once the sign of conformity, is confronted by a rival contender.

But as the once-ubiquitous revolutionary model becomes sidelined, styles that formerly signaled opposition are becoming just another form of self-expression. In the relative freedom of modern Iran, men have abandoned the fanfare of the great historical volte-face, and are sounding the death knell for the facial icons of Iran’s recent past. The disappearance of these traditional symbols of manhood flags the demise of the Iranian uber-male in favor of the cherub-cheeked international everyman.