London

Rosalind Nashashibi

Institute of Contemporary Arts

September 10–November 1, 2009

When photographer Jeff Wall said that experience and evaluation are richer responses than the gestures of understanding and interpretation, he was probably talking at least in part about intuition. Such wisdom comes in handy when thinking about Rosalind Nashahibi’s art. The London-based artist’s 16mm films frequently reference the visual and material codes of cinema, while operating from within the medium in a manner that manages to mimic human experience: In the same way that the mind leaps from one thought to another, from one association to another, so, too, do this artist’s works.

Such leaping was evident in Footnote (2008), one of the shorter works featured in Nashashibi’s solo show at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts. In laying bare the mechanics of film and of imagination more generally — the jumps, cuts, leaps, and translations — Nashashibi literally staged a simile. She filmed Helke Bayrle (whom she had also used in an earlier work, Bachelor Machines Part 2 (2007) with her husband artist Thomas Bayrle, as part of a reenactment of an Alexander Kluge film) sitting up in bed reading a book. Each time Helke’s gaze dropped down to the page to read a footnote, we cut to the static image of a green ceramic garden frog on the edge of a stone pond. These two images looped continuously, with the only difference between sequences being the blue, red, and green filters that colored the screen. It was a simple manifestation of the random jumps and associations of any thought process, and formally toyed with the staccato visual possibilities of the film reel.

The meeting of the ordinary and the quasi-mythical ran throughout Nashashibi’s five films and two sets of photographic works on show. The meeting was most apparent in Jack Straw’s Castle (2009), arguably the least accomplished and engaging of the works. The seventeen-minute, 16mm film, set in a London forest-park, felt more like one hundred seventy minutes of staged footage lacking, at least for this viewer, any interesting references or associations — except perhaps for the shots of charcoal drawings and oil paintings of half-animal, half-human mythological creatures. In the literal, demonstrative way in which Nashashibi employed them, they seemed — perhaps a bit strenuously — to allude to the “dream space” of cinema. This is also in turn how they lost their peculiarity.

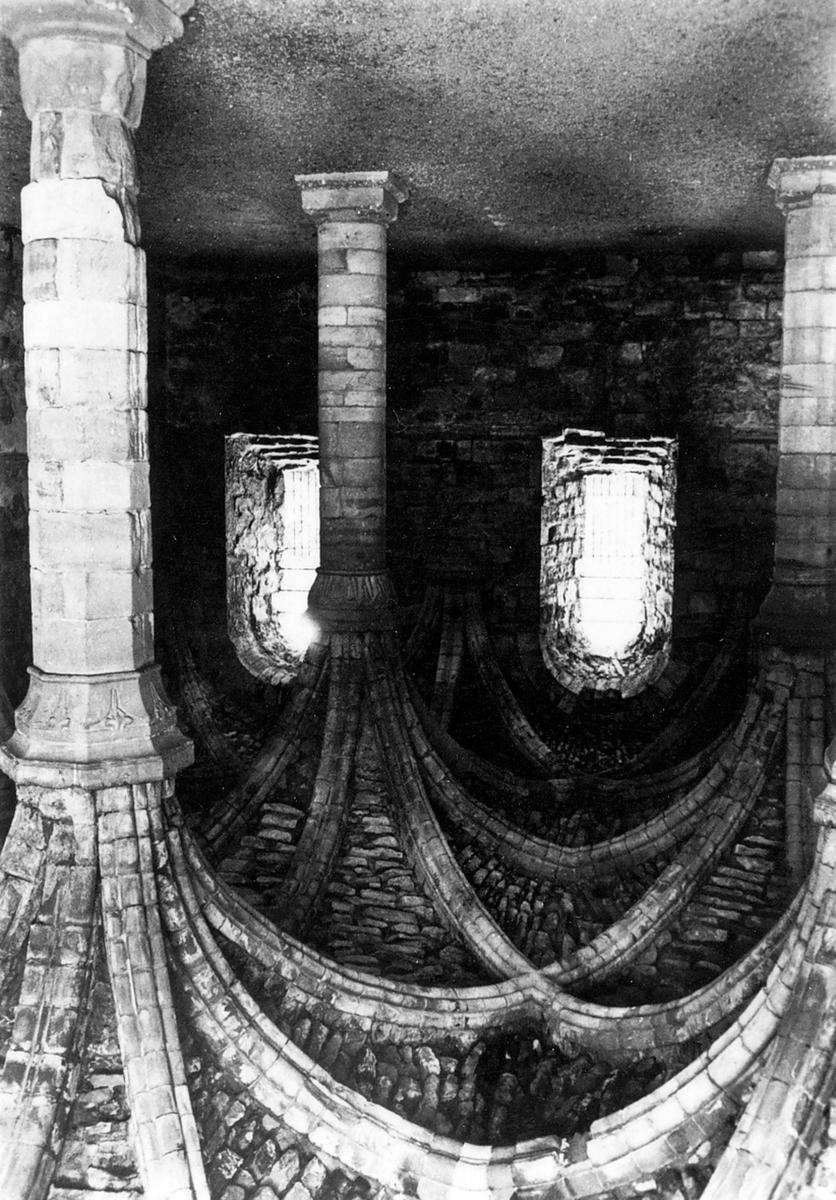

Where Nashashibi’s use of the old and the contemporary, the ordinary and the mysterious, was most effective was in a series of black and white photographs called Abbeys (2006). Despite being easy to miss in the corridor en route from the lower to the upper galleries, these four relatively large prints of abbeys — close-ups of arches, pillars, and cloisters — appeared either to be hung upside down or to picture inverted reflections, as on a lake. Though at times they may have appeared gratuitously anthropomorphic, resembling gaping mouths, it was their cold mystery, uncanny positioning, and the feeling that hanging that way, they were bound to fall and crumble down to earth, that was most intriguing. The photographs pushed viewers to engage with the medium and the object anew.

Despite a general tepidity and unevenness throughout the exhibition, Nashashibi had her moments. In the muffled, 16mm projection Eyeballing (2005), for example, we witnessed how the banal and the everyday can take on hidden meanings, how the simple can be complex, and how the accidental can be made purposeful. In the urban landscape of New York, Nashashibi stood at some distance and filmed policemen chatting and coming in and out of NYPD headquarters. These shots were interspersed with seemingly innocent, steady shots of pairs of windows, public water fountains, playground structures, pearl earrings and a necklace in a shop window, and large waterfront binoculars, all presumably chosen for their (again) anthropomorphic facial elements — all had eyes and mouths. Like the policemen, these city fixtures watch and survey us, even when we are least aware of it.

Finally, the cinematic borrowing that Nashashibi accomplished in The Prisoner (2008) was striking, making for a remarkable piece. Inspired by Chantal Akerman’s obsessive and haunting film La Captive (2000) — a tale of suspicious love that ends tragically — and named after the fifth volume of Proust’s novel In Search of Lost Time, the twin-screen projection of the same reel being shared between two projectors enacted an entrapment. We followed a blonde woman dressed in black as she hurried through the concrete mazes and structures of London’s Southbank Centre. On the adjacent “screen” we saw the very same scene with a few seconds’ delay, the time it took for the film to feed into the second projector. The sonic accompaniment was a dramatic Rachmaninoff composition and the sound of clicking heels. Caught in the reels — as though following herself from one projection to the next — the actress was a prisoner of cinema and of neurotic love. We found ourselves equally caught up in this cyclical, seductive loop. Still, this work may very well mark the extent of the show’s seduction of visitors, mostly safe as it was. Nashashibi’s solo show begs the question of whether being merely referential and safely metaphorical within a cocoon of quirky, tried and true (and impressive) tropes is sufficient to produce engaging and engaged artwork.