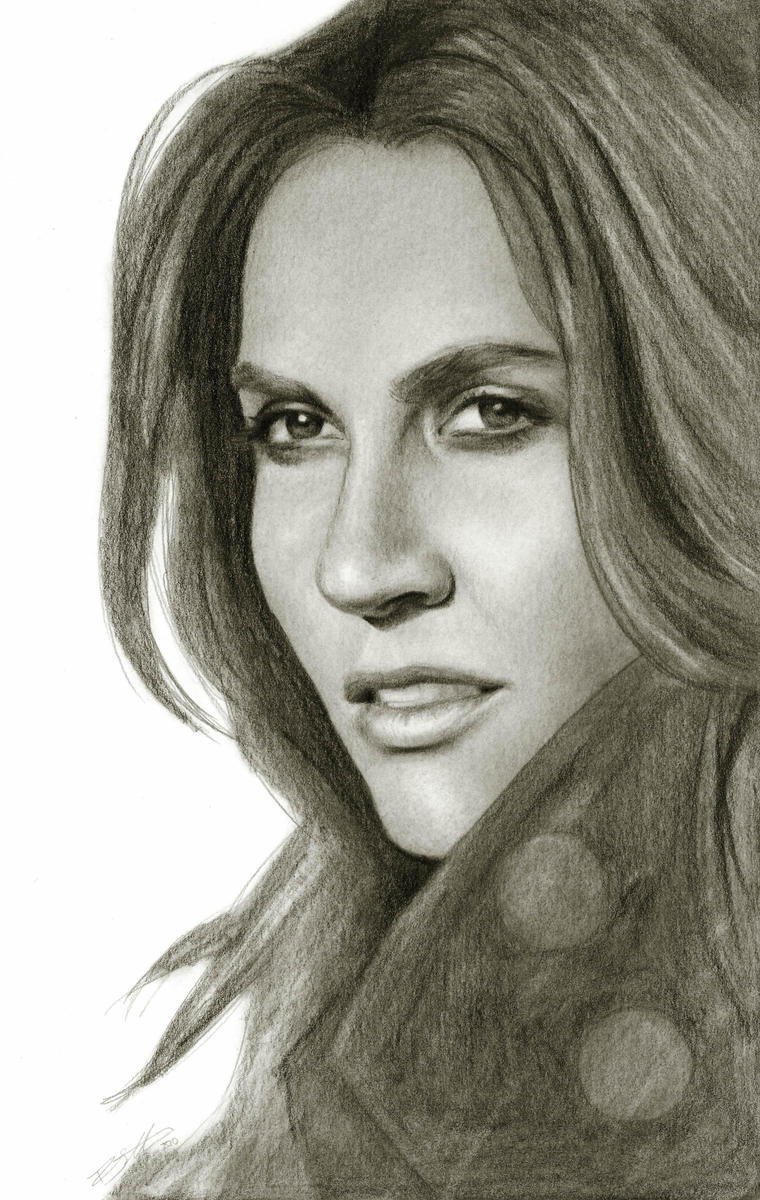

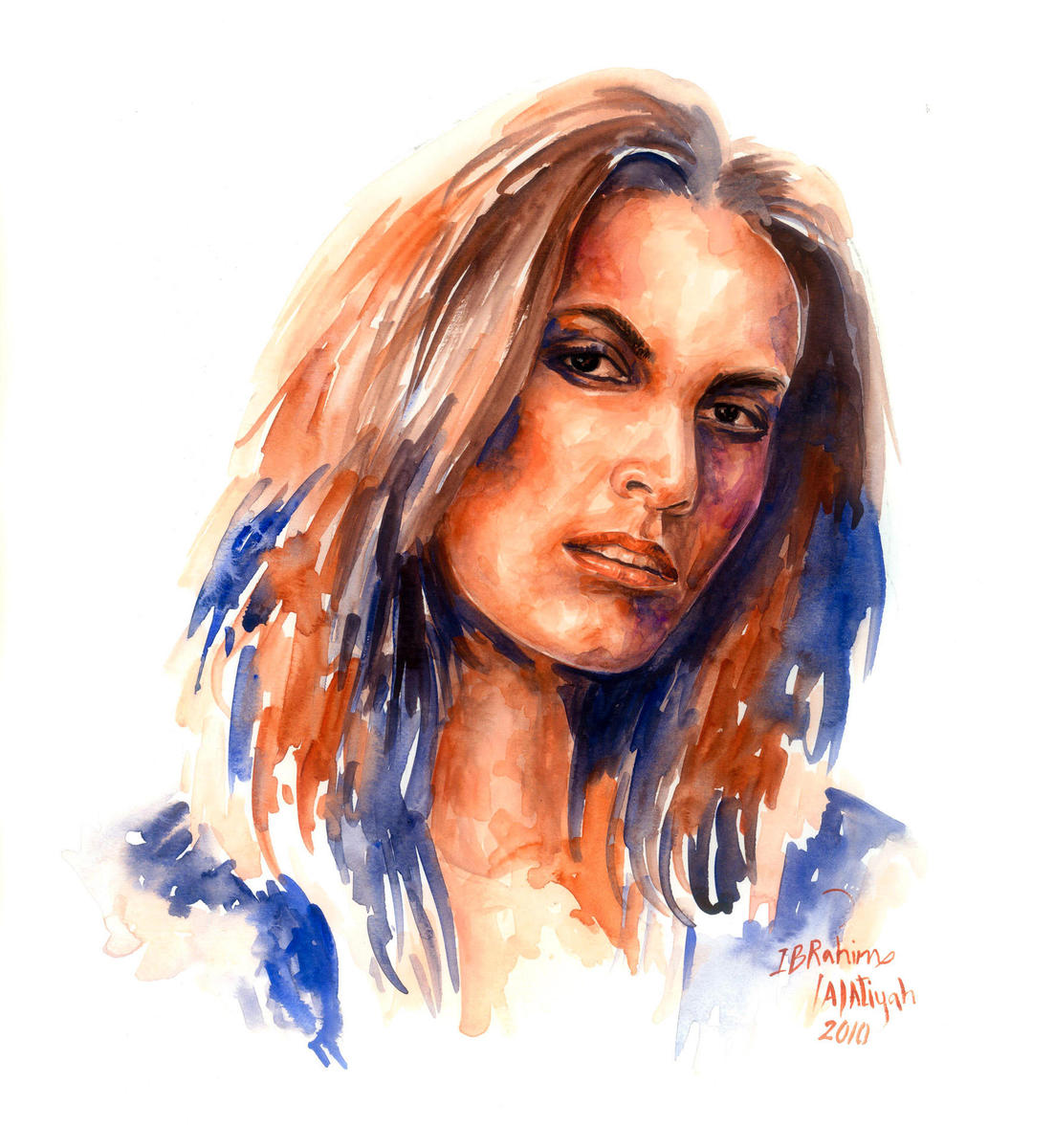

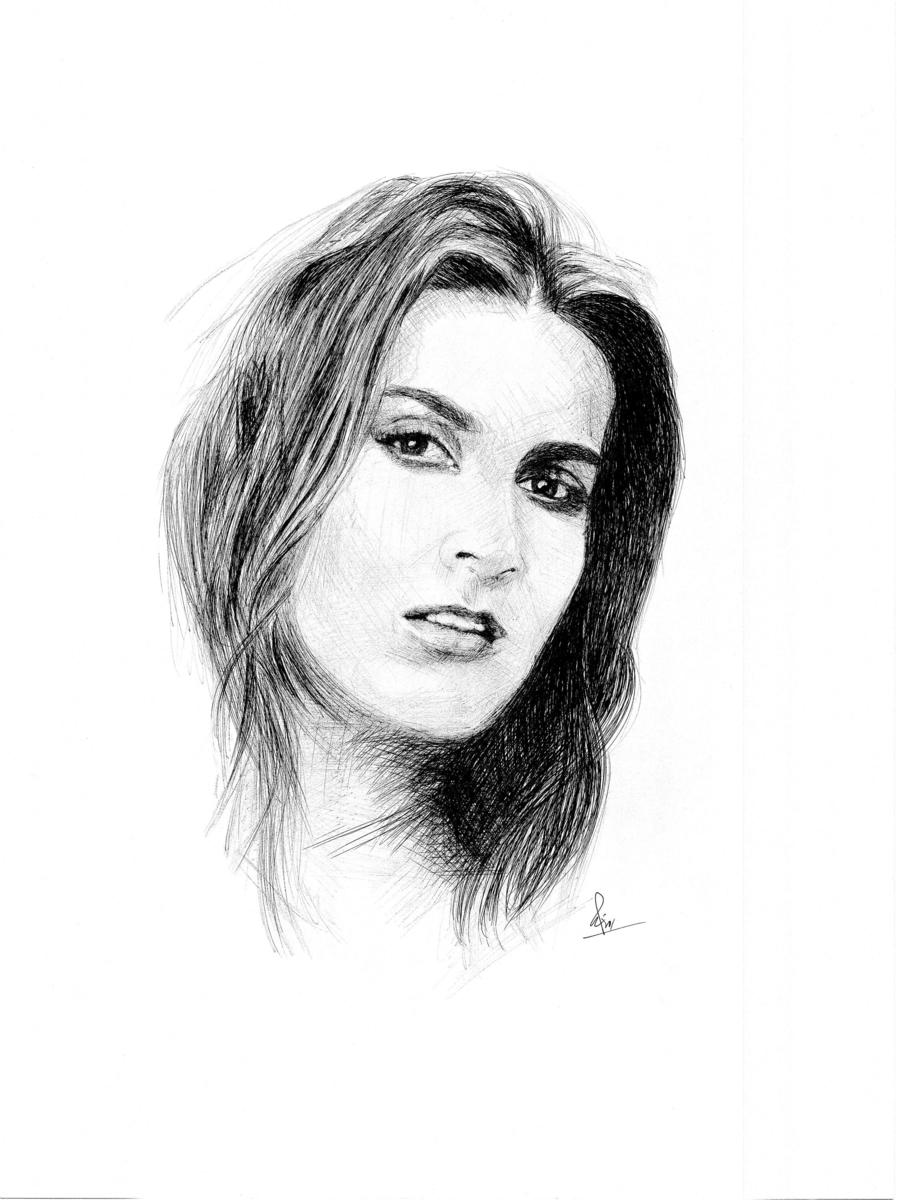

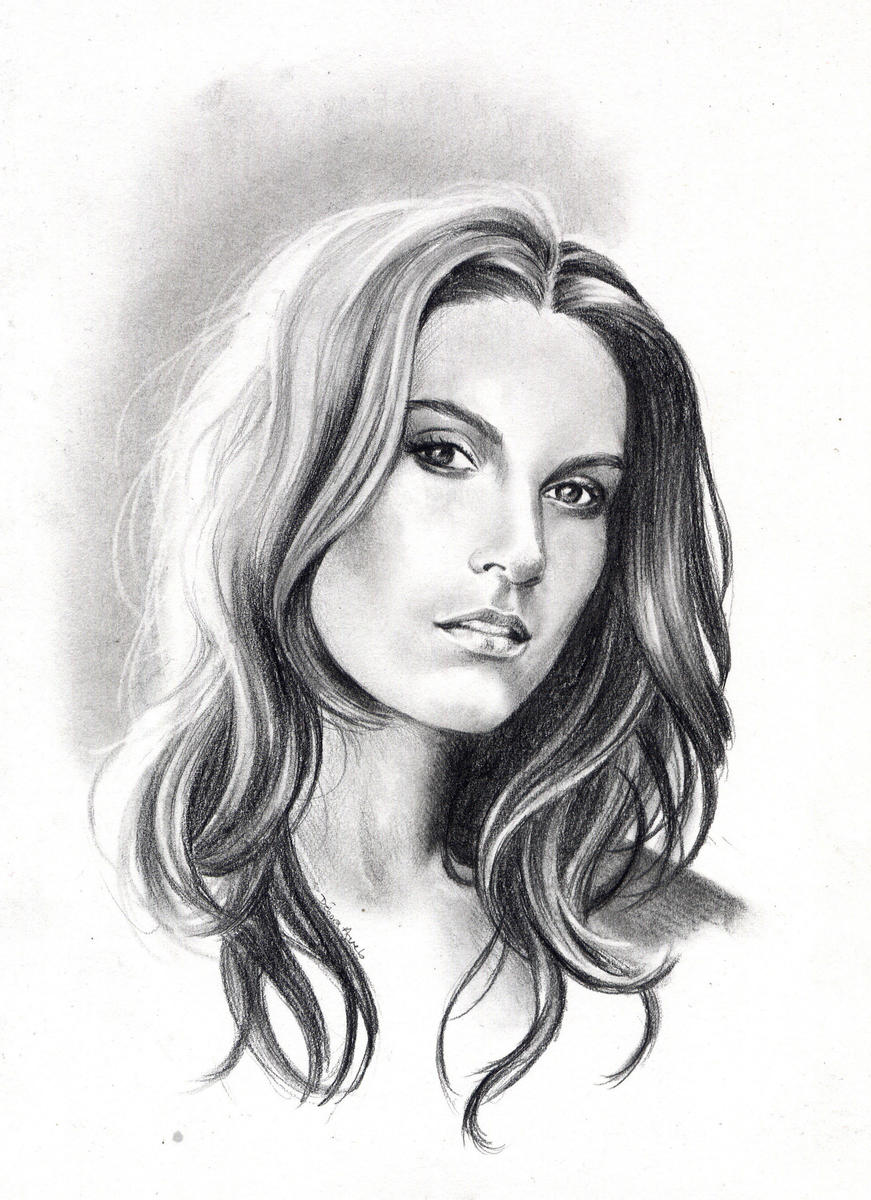

Most every aspiring beauty queen hopes for world peace. Nazanin Afshin-Jam is more specific. Winner of the 2003 Miss World Canada competition and runner-up for Miss World 2003, the singer-model-actress has used her fame and fortune to underwrite a program of humanitarian activism that has seen her traveling the globe — helping tsunami victims in India and Sri Lanka, aiding fistula patients in Ethiopia, raising awareness about bear-bile farming in China.

But Afshin-Jam is best known, outside of Canada at least, as the founder and president of Stop Child Executions, an NGO that opposes the death penalty for children and has fought to publicize the cases of more than 140 minors on death row in Iran. (In Iran, boys are eligible for the death penalty at fifteen; girls, at nine.) Stop Child Executions grew out of the campaign to save the life of Nazanin Mahabad Fatehi, an Iranian girl sentenced to hang in 2005 for stabbing a man who had tried to rape her and her fifteen-year-old niece in a park west of Tehran. An international media blitz led by Afshin-Jam culminated in January 2007, when the court reversed Fatehi’s conviction.

Afshin-Jam’s interest in Iran is personal. Born in Tehran at the height of the Islamic revolution to politically active parents, she and her family fled to Canada. She has been a harsh critic of the Islamic Republic; in 2008 she organized the “Ahmadinejad’s Wall of Shame” rally to protest the Iranian president’s address to the United Nations General Assembly. “Someday,” the title track from her 2007 debut album, is a disarmingly catchy four-minute pop-orchestral assault on the “regressive revolution,” complete with a truly epic music video.

No stuffed bra, Afshin-Jam has studied international relations and politics at the University of British Columbia and at the Paris Institute of Political Studies; she’s currently working on a master’s. She flies airplanes as a hobby, and achieved the highest rank in the Royal Canadian Air Cadets: warrant officer first class.

Lisa Farjam: I was wondering if I could ask you first about your leaving Iran during the revolution. How much do you remember about that time?

Nazanin Afshin-Jam: I’m sure my family having to escape Iran shaped me in some way, but I can’t say that I remember the chaos or anything surrounding it. Because I was only a year old, but probably on a subconscious level, it affected me. I mean, of course, moving to Canada and asking my family questions about why our family had to be separated from my extended family: my grandmother, my aunts and uncles. You know, you don’t understand as a kid, why. So, little by little, as my family told me stories about Iran, maybe in some sense it made me start to understand that things are not always fair in life and that there are injustices. But I’ve always been sensitive to other people’s pain — if any of my friends or family were hurting in some way, whether it was physical from falling or just being sad or upset. To this day, when my girlfriends break up with a boyfriend or just… I internalize it, I can feel it my own stomach, in my own heart. That’s part of why I want to help people so desperately, to take that pain away in some way.

LF: Do you feel connected to being an Iranian? I was born in New York, and I didn’t feel connected to the Iranian part of me until I went there when I was thirteen. But you’ve never been back, I take it? Do you feel very connected, or do you feel kind of estranged from that part of your heritage?

NAJ: I feel half and half. I feel very much Iranian, and I also feel very much Canadian. Iranian in the sense that growing up in an Iranian family, you kind of inherit the culture just through osmosis — the way Iranians think and translate and feel, the poetry. It’s almost in our blood. I guess what separates me from my Canadian friends is the real connection with family, and that’s something that I’m really grateful to our culture for. That deep sense of unity… it being really important to stick together, to work things out, as a family. In some sense it can be really annoying, of course, but I really cherish it. And, you know, the strong push toward education and higher learning. That’s definitely, I think, an Iranian trait. So in that sense, yes, I’m very Persian. As a child, I guess I was more Canadianized, just because you adopt whatever’s around you, but as I grew up and as I thirsted to learn about our culture, I became more Iranian.

LF: Yes, of course.

NAJ: And, you know, there weren’t many “ethnic people” in my classes at school, especially when I was younger, so I had to prove myself. When I started acting, too, there were agents who tried to get me to change my name — “It’s too hard, no one will ever remember it.” But I stuck it out. My parents were very supportive of me, very loving. And very open. They didn’t push me… I know a lot of Persian families where the children are forced to become a doctor or a lawyer or an engineer, whereas my family said, “Follow your heart, do what you like.”

Later, when I started working on human rights cases, I became more in contact with, you know, lawyers and human rights activists, the general public. I started receiving thousands of emails a year from Iranians, sharing stories with me, the hardships of daily life, asking for help in some cases. My Persian was never really great, but it’s gotten a little bit better because the work I’ve been doing.

LF: How has your life changed since the success of the Help Nazanin Fatehi campaign?

NAJ: After Nazanin was freed, I thought, “Okay, she’s good, I can go work on some other issue now.” But literally the next day I was contacted by other people struggling in Iran, family members of jailed children, asking me for help. And I had this sense, almost, of responsibility now, that people were looking to me to help them with this cause. I looked online for organizations that focused on child executions, and I couldn’t find anything. Of course, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch will do urgent action responses and the like, but there wasn’t anything that concentrated on this particular issue. So Stop Child Execution was born, and I basically recruited volunteers, people that had been involved in the Help Nazanin Fatehi campaign, and asked them to join me. That’s kind of how it started, four or five years ago.

There are more than 160 children on death row in Iran now, with a handful of other cases in four other countries. So the day-to-day work is raising awareness by writing articles or visiting different government officials. I’m going to be participating in a TED [Technology, Entertainment, Design] event in Vancouver. We create mini-documentaries, organize rallies and speeches — you know, just regular NGO things. So that’s taken up quite a bit of time, but my heart isn’t just set on the case of child execution. It goes beyond. That’s why I concentrate a lot on general human rights abuses taking place in Iran, especially when it comes to women’s rights. That’s a particular interest of mine. And, again, not just Iran. I’ve also campaigned on behalf of people in China and Burma. Darfur. Wherever I’m needed, basically — if somebody asks me, I try to make time to help. And if I’m really passionate about something, I’ll go for it. A few years ago, I campaigned with my sister to try to help the bears in China who are being caged and having their bile extracted for China’s traditional medicine. They’re under horrid conditions, with catheters placed into their gall bladders to get this unnecessary bile.

So just anywhere, really, I try to help. Most recently, I guess you could say my heart was even more set on seeing a free and democratic Iran in the near future, because that’s really the root of the problem in terms of these other human rights abuses.

LF: Inshallah one day, soon…

NAJ: Yes!

LF: And I think it’s just brilliant how you use the Miss Canada title and Miss World runner-up to your advantage in this way. Can you feel the impact of those titles? Did you gain legitimacy? Do you feel that it affected how you were able to approach people? Did you feel that it changed things in any way?

NAJ: Certainly for me it helped. It was kind of a strategy. I had been working with the Red Cross for a while, and I was reaching people, but I just knew that I had to reach more people. And as soon as I won those titles, doors just opened. The media would listen to what I had to say much more. It’s a sad reflection on society today, but it’s just the reality. It made people just listen extra-hard. And you know, it was a blessing and a curse at the same time. You know, stereotypically people think of beauty-pageant contestants as ditzes, just interested in glitz and glamour, waving and smiling. People don’t realize that pageants have evolved with the times and that there are certainly people entering these competitions that really want to make a difference in their communities and societies. So I think once people learned what my aims and ambitions were, they changed their minds, but I almost had to prove myself double-time.

LF: Was there any backlash to all that?

NAJ: At the beginning I did get some negative emails, mostly from western countries like Canada and the US, that said, “By entering these competitions, you’re promoting the exploitation of women.” But you know, it really does matter what pageant you enter. Miss World’s motto was “Beauty with a purpose,” and their whole aim was to raise money for children’s charities, so I chose that pageant to pursue, and it worked to my benefit and to the benefit of a lot of people who were needy. So, yeah, I don’t regret it.

LF: I imagine you must have had to lean quite a bit on your family for financial support when you made the move to become a human rights activist — fundraising is such an enormous task. I’m sure it’s an ongoing daily battle.

NAJ: It is. It’s a major concern. I mean, to put on a rally, it takes thousands of dollars. To fly somewhere to speak to people costs money. And at the beginning, I was borrowing a lot from friends and family, and they were very generous. I had savings, too, from my days as a model. But those reserves are gone now, and I have to think about the next step. I’ve never really had a real fundraiser before. There was this one lady in Chicago who put on our first fundraiser just out of the kindness of her heart — we raised a few thousand dollars there. But Stop Child Executions and the Nazanin Fatehi campaign have been almost entirely staffed by volunteers. Now it’s come to a point where if I want to do more interesting things with the organization, we’ll have to raise money. I’ve gone back to school, too! Which costs money. I mean, we’ve managed to get by, and I’m sure a lot of NGOs are in this position. But knock on wood, we’re okay.

LF: Are you going to school full time?

NAJ: Yes, I’m doing my master’s in diplomacy with a concentration in international conflict management. I mean, it’s an online program, so I’m able to do it from wherever I am — I do a lot of reading on airplanes, writing essays when I can find the time. But it’s taking up most of my time.

LF: Did you begin your modeling career with the idea of saving money for some higher purpose?

NAJ: I started modeling at the end of my high school years, when I started university. I was basically raising money for my education.

LF: Again with the higher purpose!

NAJ: Yes!