Alexandria

Alexandria Contemporary Arts Forum

Various venues

April 18–May 8, 2010

Omar Moustafa’s 12 Minutes of Spectacle opened with a young man — the artist himself, we soon learned — moving about frantically in Pull and Bear, a popular Spanish boutique. The video, minimally constructed, featured the artist systematically browsing rack after rack of the stuff of generic youth fashion. A young man’s voice was heard reading excerpts from Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle in affected, school-learned English. Moustafa’s first work to date, the piece captured the essence and primary concern of the recent group show in which it appeared. Curated by artist Mohamed Nabil and held at the Alexandria Contemporary Arts Forum, the show’s theme and central concern seemed to be the young artist as wayward consumer.

Ahmed Nagy’s two-channel work Random Systematic Research aimed to “find the soul” of the shopping mall, or so said the exhibition’s curator. One screen revealed a slideshow of trade buildings and symbols of the capital economy worldwide, while the other screen showed the artist browsing through Wiki hotlinks informing us as to the nature and amount of energy that shopping malls exude. Three of the artist’s friends could be overheard having a muffled conversation about the various approaches they each take to shopping. The complete work was a needlessly didactic exploration of the relationship between the shared ethos of globalized information technology, hyperlinked data, market economies, and the everyday consumer experience.

Aya Tarek’s wall mural of superman, larger than life, exemplified the advertising pop aesthetic one typically associates with shopping malls. The work was big, bold, and beautiful — evocative of KitKat billboards on the Cairo-Alex highway. It was clear and direct — appropriating a visual language already available and widely in use — and meticulously made.

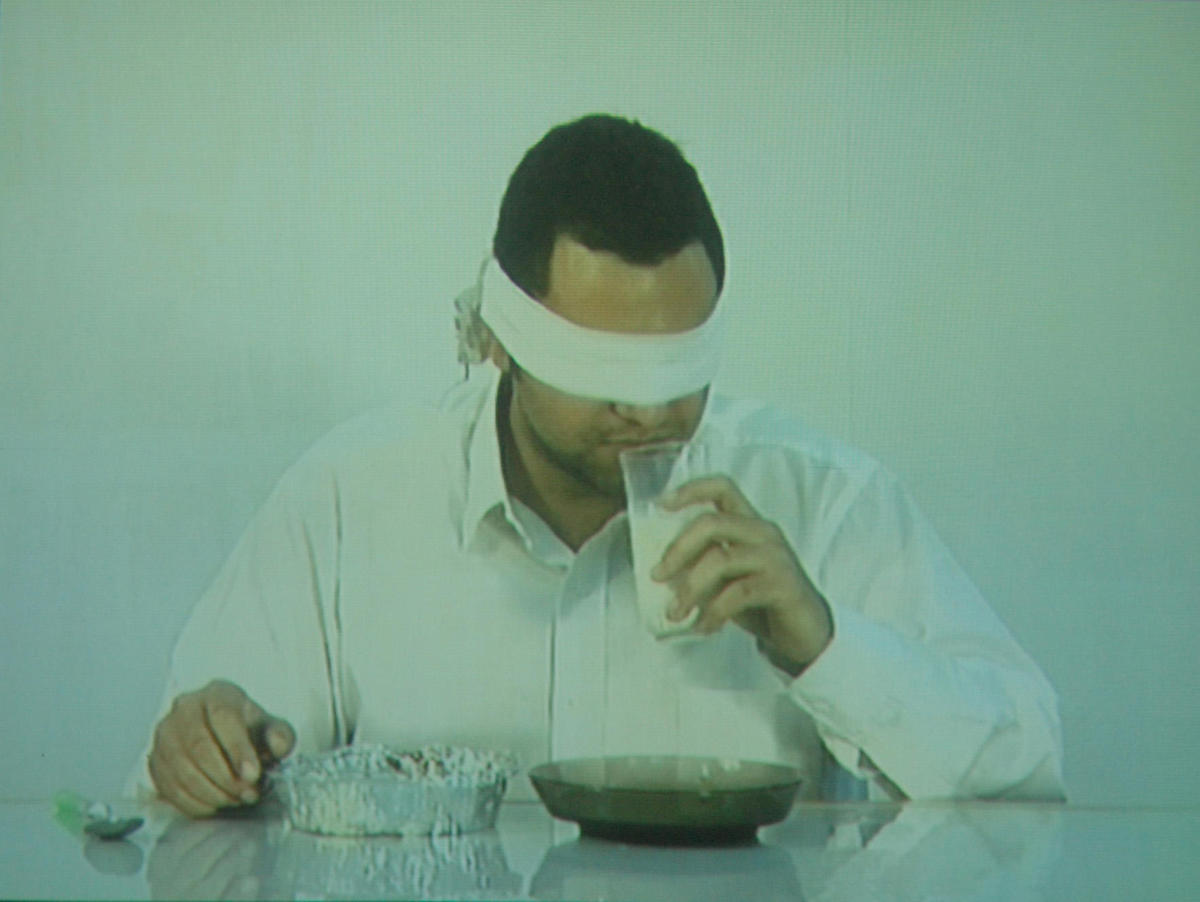

Mohamed Nabil’s own twenty-minute video Five Meals centered on a blindfolded man eating five different fast-food meals and reflecting between bites on the cultural origin of the meals he was having. The work became all the more interesting when the artist explained that the actor’s fee was reduced every time he accidentally uttered a place name that could indicate the provenance of the food.

In the corner of the same room as Nabil’s piece, an unspectacular display of photographs and printed advertisements evoked Egypt’s decaying European department store culture of the 1950s and ’60s, a culture that predated the American-style mega-malls mushrooming around Cairo and Alexandria. The work, I was told, was a collective effort by the artists to create a research display of sorts. Flipping through an album of newspaper cutouts, I lingered over an illustration of a little boy and girl kissing, an advert for the recently facelifted Omar Effendi (originally Orosdi Bak, founded in 1856 by an Austro-Hungarian army officer). The eclectic arrangement advertised one-pound-ten-piaster flights from the capital to Alexandria, and displayed Hanneaux wrapping paper, the type any sensible Egyptian grandmother would keep to line her drawers.

The collectively gathered snippets of material, grandly titled In the Sixties We Trust, provided an apt narrative to changes in consumer culture in Egypt. In his curatorial statement, Nabil stated that this collection brought into context “the prevalent mechanisms of production and consumption of the Sixties, the resonance of which carries into certain areas of our daily lives.” Since the 1990s, government efforts have pushed for the privatization of many of the one-hundred-plus year-old department stores. Those ventures, we learned from the broadly contextualizing gesture, are also slowly giving a facelift to vintage-style stores, turning them into contemporary shopping outlets.

Mohamed Mansour’s series of untitled photographs — taken in and inside the vacant parking lot after hours at the Carrefour City Center on the outskirts of Alexandria — was the only work that inverted the idea of shopping malls as the mini-cosmos of a contemporary culture of excess. It simply revealed the mall to be what it most fundamentally is: a physical public space. In this way, the images offered points for contemplation amidst the other, often frenetic, works on display. At their best, the individual photographs were strongly reminiscent of Candida Höfer’s pictures of interiors, in their attempt to capture the peculiar psychology of the architecture and social space. Mansour’s photos made apparent the universality of the phenomenological and psychological experience of that particular architectural space and mall culture at large.

In the end, Nabil’s ‘Shopping Malls’ exhibition yielded a handful of pleasant movements, some perhaps intentional, others not. Critiques of consumer culture aren’t breaking news, nor are they particular to Egypt; but it was in those moments when the particularity of Egypt was laid bare — or alternatively, when the zeitgeist of consumerism was extended into the realm of arts production — that this exhibition of younger artists was most interesting. In shifting from “artists as producers” to “artists as consumers,” the show escaped the realm of the one-liner and, miraculously, made itself the subject of the very critique it was putting forth.