London

Group Material: A History of Irritated Material

Raven Row

February 25–May 2, 2010

The late Félix González-Torres used to call Group Material (GM), the New York–based artist-activist collective of which he was a core member for some time, “the best-kept secret in the art world.” Although the group participated in two Whitney Biennials, Documenta 8, and major shows at Dia Art Foundation and P.S. 1 Contemporary Art Center, their legacy seemed, for a long while, subject to critical amnesia.

It’s difficult to understand this lapse now, given the biennial circuit’s recent tendency toward activism and community-orientated dialogues; GM’s strategies can be seen echoing through (or repeated in) everything from What, How & for Whom’s Istanbul Biennial to the work of Yael Bartana, Lara Almarcegui, Sharon Hayes, and Harrell Fletcher. It was always González-Torres’s hope that GM would produce a book; with the publication of Show and Tell: A Chronicle of Group Material, this hope has been marvelously, if belatedly, fulfilled. Published by London’s Four Corners Books, it comprises comprehensive documentation of the almost fifty projects the group carried out between 1979 and 1996, when founding member Julie Ault, who edited Show and Tell, brought it to an end.

“How is culture made, and who is it for?” This was the question that GM repeatedly posed. Fiercely self-reliant and community-based, theirs was an insistent effort to reshape the relationship between those who produce depictions of the world and those who view and consume them. The activism of the 1960s was the foundation for their interpretative enactments, but the overall project was — as core member Doug Ashford notes in his essay here — formed in the early 80s, a period of attempted historic erasure during which the progressive economic and cultural changes of the 60s were under fire. Reading Show and Tell, it’s as though Group Material — with its focus on US foreign policy, AIDS awareness, and the other central issues of the culture wars — existed a world away from the excesses of New York–based contemporaries like Julian Schnabel. The icy-cold gaze the Pictures artists threw over the operations of consumerism wasn’t so far removed, but rather than appropriating sleek advertising, Group Material’s output — which spanned billboards, public forums, and magazine inserts — consciously resembled the forms of the political vanguard.

A key early influence for Group Material was the teaching of Joseph Kosuth, under whom Tim Rollins and many other early members studied at the School of Visual Arts in the mid-70s. Kosuth, among others, called for an art-making of direct engagement with communities and individuals. In his essay “What Was to be Done?” Rollins writes, “This was work that actually transformed the situation that was the impetus for the work.” This was political art that was not about politics, not about representation or reportage, but about dialogue, and made in concert with the community.

In November 1980, the Village Voice reported that Group Material’s opening show — a survey of cultural activism titled, in typically deadpan fashion, ‘Inaugural Exhibition’ — was so successful that they had “already earned the enmity of New Wave artists far and wide.” But this early success was also fraught; just two months later, minutes from their weekly meetings have Rollins calling for the group to be split into two autonomous bodies. An unexpected pleasure of Show and Tell, actually, is the inclusion of careful minutes from the group’s meetings, which were required in order for GM to be legally registered as a nonprofit.

Looking through the publication, it’s hard not to remark upon the irony that, despite the group’s professed wariness toward institutions, their internal workings were required to mimic those of institutional bureaucracy. (Perhaps this was the inevitable outcome of attempting to make artwork comparable to the apparatus of democracy.) Ashford spoke of the collective’s “anarchic exchange”; for anarchists, they were well organized.

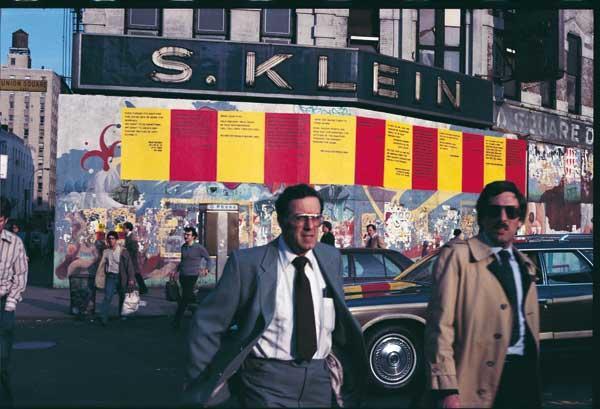

In 1983 they abandoned their storefront at 244 East 13th Street in order to function nomadically, turning their attention away from fixed exhibitions to utilize different distribution models and public spaces. This comprised renting billboards and ad space on subway cars, paying for inserts in the New York Times, and taking exhibitions to the street — “all refusals of established frameworks for the organization of art,” according to Ashford. This focus on dispersal and direct communication, rather than on autonomous art objects, meant that for a long time there was no official Group Material archive. Their output wasn’t maintained in any special or careful way; shows were documented but weren’t intended to last.

The publication of Show and Tell is an important corrective to that and marks the second half of the group’s careful self-institutionalization. In the summer of 2008, Ault had gathered what she calls the “physical traces of Group Material” and taken them to the Downtown Collection at the Fales Library of New York University. Her own collection was augmented by donations from other members, particularly Ashford, of material that had hitherto remained scattered since the group’s decentralization in 1983. Ault acknowledges that, stored under beds or forgotten in the backs of closets, this was always an idiosyncratic archive, necessarily incomplete and always expressive of individual members’ habits. When members left the group — as many did, including Rollins, who departed in 1987 to pursue K.O.S. (Kids of Survival, an afterschool group he ran in the Bronx) — material was often not turned over. Elsewhere the absences were more final; five of the twenty core members are now dead.

The Downtown Collection is a good home for projects not intended to last. It was founded in 1993, with a focus on New York downtown culture, by Marvin Taylor, who regards archives as “false evidence.” The gaps, he thinks, are where the good stuff is. Ault intended this institutionalization of the GM archive to trigger an opening up, rather than to signal a closing of the casket. It’s open to all, for whatever purpose, including reproduction rights.

While Ault intends this archive to be available for use and reworking, the collective’s temporal, context-specific practice means that there are obvious limitations on recreating installations from the archive. The past and its contingencies are irretrievable; as Ault puts it, “Contexts cannot be replicated. It is impossible to reproduce the climate of circumstance and perception and understanding for events.” Collaborations often went way beyond the immediate circle of the group, and this social aspect of production would necessarily be removed, leaving only the physical side of the process. A small presentation of Group Material’s work recently at Raven Row in London — as part of ‘A History of Irritated Material’ — was, in this sense, a rare thing. Curated by Lars Bang Larsen, the show positioned itself as an archive of sorts and marked a telling shift in GM’s canonization. Their intentionally ephemeral collaborative activism is now carefully maintained and is in the early stages of being placed alongside the archives of other once-marginalized fellow travelers (other artists in the show included Sture Johannesson, Lygia Clark, and the Moscow collective Inspection Medical Hermeneutics). This is a good thing.

González-Torres’s AIDS-related death in the fall of 1996 cast a shadow over Group Material. Ault and Ashford, who had for some time worried that their relevance was faltering, brought operations to a close. But they remain more than relevant. As Ashford writes, “Today’s ascendant culture of war and its accompanying economic collapse bring home many of the state-designed public fictions initiated in the 1980s.” In a recent talk at Raven Row, Ault wondered aloud, “What tense is the archive in?” The answer, as Show and Tell demonstrates, is surely the future.