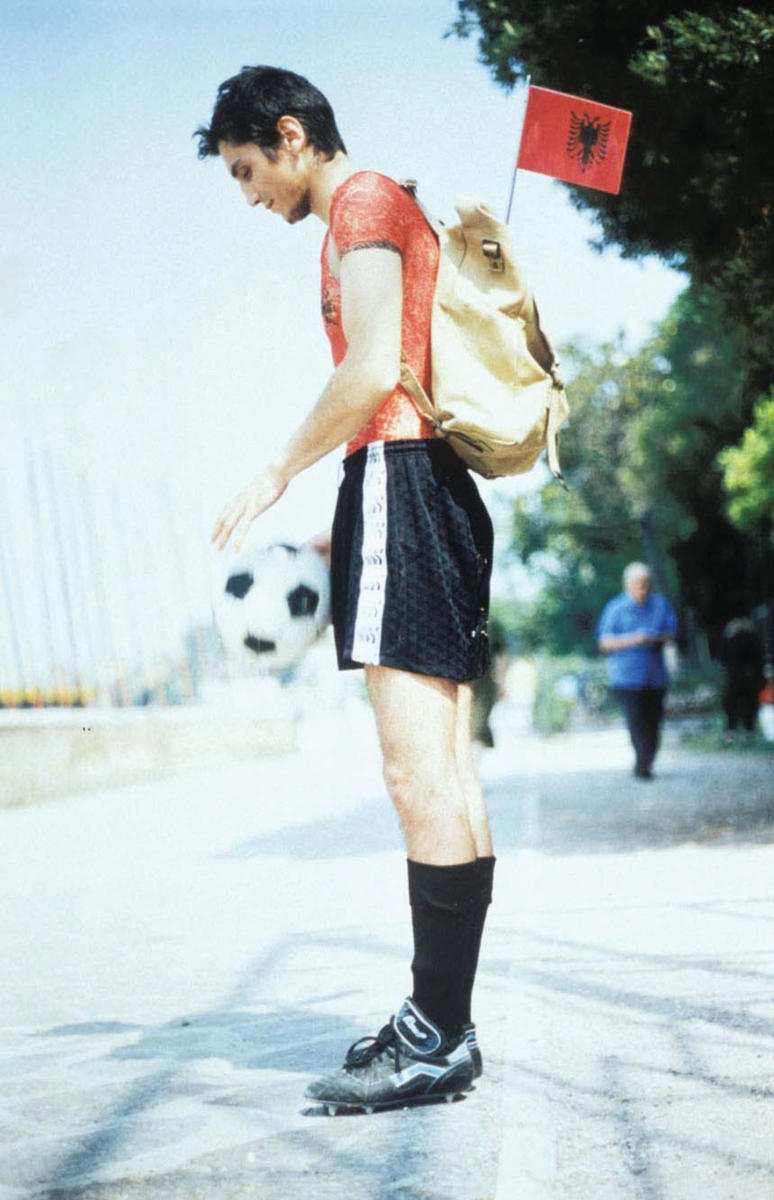

In the summer of 1997, dressed in the black shorts, cleats, and red jersey of the Albanian national soccer team, carrying a ball and sporting a backpack outfitted with a little Albanian flag and a radio broadcasting a soccer match between Italy and Portugal, a young Kosovar Albanian artist named Sislej Xhafa roamed the grounds of the 47th Venice Biennale asking other visitors to play soccer with him. That year, the teeny Balkan republic of Albania was not among the countries represented in Venice — despite the fact that only the Adriatic Sea separates them. Xhafa had decided to change that, transforming himself into an artwork he would later call the Clandestine Albanian Pavilion, an unassuming performance that raised difficult questions about the countries invited to such rarified events and why those that are not, are not. Why, for example, does Luxembourg — with fewer than 500,000 inhabitants — warrant a pavilion, when India — with more than a billion — does not? And who gets to decide?

Clandestine Albanian Pavilion introduced biennale-goers to a constellation of concerns that have suffused this now thirty-seven-year-old artist’s subsequent work. Its mobility and surreptitious, nominally criminal nature (Xhafa had entered the giardini illegally) spoke to the tenuous circumstances of the hundreds of thousands of Albanians who emigrated — often illegally — to the West during the early 1990s. And Xhafa’s decision to appear in the uniform of the Albanian national soccer team highlighted not only the nationalist character of events like the Venice Biennale, but also the degree to which sports and leisure may become stages for political negotiation (witness the intense politicization of the Iraqi soccer team’s exploits in the 2004 Olympics).

In hindsight, it seems entirely appropriate that Xhafa’s performance — the work that first brought him widespread recognition — was predicated on questions of absence and invisibility. Although the Pavilion performance was an artwork, realized in the context of a major international exhibition, it hardly announced its status as such when it was performed. Rather than a young Albanian artist making a political statement through his art, viewers met a young Albanian man (and a fellow visitor to the biennale, at that) cheerfully encouraging their participation in an activity of communal recreation. In a way, the biennale audience’s failure to recognize the work as a work — abetted by the artist’s subterfuge — mirrored the marginalization of Albanian immigrants in Italian society. At the same time, Pavilion provided a potent testimony to the very real impact of immigrants and other “invisible” constituencies on the daily life of their communities.

In the ten years since his Venice debut, Xhafa has developed a body of work that has subtly and consistently drawn attention to the invisible, often unjust, systems that structure our lives. A consummate bricoleur, he eschews allegiance to any one style or medium, pursuing instead a kind of aesthetic realpolitik. Issues are approached obliquely rather than confronted head-on; and while unjust conditions are exposed, solutions are rarely offered. The challenge, as he sees it, is to be provocative without being didactic, to unsettle, not to hector. Only in that way can dialogue remain a real possibility. Xhafa’s work is “political” in that it disrupts the order of things, the allocation of experience — what Jacques Rancière has described as the “distribution of the sensible,” shaped by various forms of policing, both juridical and social. It’s a politics of interruption, upsetting the configuration of forces determining what is visible and what is not, what forms of speech are understood as discourse and which are only perceptible as noise, who is designated as a speaking subject and who is merely spoken to. No matter the circumstances, for this artist, indifference is never an option.

The paradoxical invisibility of Europe’s large (and growing) immigrant communities has been a particular focus of Xhafa’s work. In Elegant Sick Bus, first performed at the 2001 Istanbul Biennial and reenacted more recently in 2006 at Art Basel Miami Beach, a group of men pushed a mirror-plated tour bus through the streets, ostensibly in search of the nearest repair shop or filling station. On one level, the work highlighted what Xhafa calls the “forced hospitality” imposed on local populations by a tourist economy. But the vehicle’s mirrored surface also complicated the conventional directionality of the touristic gaze. As it was pushed through the streets, the bus itself became the spectacle, even as it reflected the image of the local community — including the laborers themselves — back onto itself.

By contrast, Xhafa’s 2002 sculpture Ali Hamadu, a four-and-a-half-meter ebony figure of a briefcase-toting Senegalese businessman clad in a designer suit, depended on the withdrawal of visual information. Ali Hamadu, said Xhafa, had to be exhibited in total darkness — a phenomenal situation in which skin color (not to mention most normative criteria for judging works of art) becomes irrelevant. In this project, Xhafa replaced Elegant Sick Bus’s effect of heightened visibility with an almost purely tactile experience, as the viewer had to blindly probe the darkened hall in search of a statue whose monumentality was perversely matched by its invisibility.

On June 21, 2000, wearing a sharp black suit, Xhafa (who cuts a handsome, swarthy figure with his ambiguously Mediterranean visage) stood under the arrivals/departures board in the railway station in Ljubljana, Slovenia. Gesticulating wildly with the manic energy of a broker on the trading floor, he called out the train schedule to an audience of bemused and bewildered travelers. Xhafa’s deceptively simple, almost Fluxus-like action — delivered in the context of Manifesta 3 — lent itself to myriad readings, not the least of which was a powerful indictment of the market-driven nature of the “art tourism” that is so ubiquitous today.

Two years later, Xhafa offered Étant donné MD 1946–1966–2002, a clever impromptu reimagining of Marcel Duchamp’s meditation on vision and carnal desire. Having arrived in Pescara to install a work in a group show, Xhafa was struck by the view from one of the gallery’s windows. Abandoning his planned installation, the artist covered the window with blackout paper and in front of it installed a small wall of rustic masonry and a plywood door with a jagged hole punched through it. As viewers, stooping slightly, peered through this aperture and a tiny hole cut in the blackout paper behind it, they discovered — instead of Duchamp’s reclining nude — a sign demarcating a Sisley boutique across the street. Étant donné directed the viewer’s gaze outward, transforming the gallery itself into a frame for the outside world. And by playing on the homophony between his own name and that of the cheesy Euro-fashion label, Xhafa ceded the moral high ground, pointing ambiguously to his own role in an economy that constantly threatens to transform art into the stuff of high-end luxury goods.

For all his Duchampian proclivities, however, Xhafa has perpetually sought ways to redefine and renew the potential of an art engagé. Barely six months prior to installing Étant donné, Xhafa had erected Job Center, a four-meter-high, thirty-meter-long cinderblock wall cutting diagonally across a busy square near the university in the northern Italian city of Torino. A neon sign, installed above an automatic sliding-glass door in the center of the wall, announced in no uncertain terms the edifice’s purported identity as an employment agency. Behind the door, however, was neither job nor center, only the same identical façade reproduced on the other side of the wall. A locally specific temporary intervention in Torino residents’ habitual trajectories through the city, Job Center’s blank façade and generic, bluntly descriptive signage nevertheless effected a crucial shift in register from the particular to the universal, translating into spatial terms the Sisyphean experience of workers caught in a cycle of unemployment and temporary, low-pay wage-labor.

Since leaving Albania in the early 1990s, Xhafa has lived a nomadic existence. Living first in London, then in Italy, and — since the year 2000 — in New York City, he’s become remarkably attuned to the positive as well as the negative aspects of what is blithely referred to as globalization. Despite a geopolitical landscape increasingly resistant to dialogue, Xhafa has maintained an intuitive commitment to the productive force of difference and disagreement. And so last fall, when he was invited to install a “non-commercial” work at the Galerie Michael Neff in Frankfurt, he responded by “installing” a professional locksmith who, for the duration of the exhibition, ground copies of the key to the gallery’s front door and sold them to visitors for ten euros apiece. Xhafa insisted that the normal contents of the gallery (computers, libraries, records, perhaps even other artworks) remain — unguarded — on the premises throughout the month-long exhibition he called MN Unplugged. But what might initially have seemed like a relatively straightforward test of the dealer’s trust quickly revealed a much more complex dynamic.

As a sort of art-world version of prisoner’s dilemma, MN Unplugged pointedly asked us to consider the slippery generation of “value” in the context of an art space. As commercial enterprises, art galleries are dependent on a certain physical infrastructure (read: the gallery itself) in order to carry out their work. Within the terms of MN Unplugged, the artist had to trust both dealer and visitor to acknowledge that the conceptual value of the art trumped the material (and functional) value of the gallery’s commercial infrastructure. In the language of game theory, within the triad of artist, dealer, and visitor, it is the artist who must cooperate and trust both of the other two players to cooperate as well. Consequently, it is the artist whose position is most precarious, for if either of the other players defects (in this case, by breaking the ethical compact initiated by the work), then the attempt to transform a zero-sum game into a non-zero-sum game is lost.

MN Unplugged called forth a notion of politics as a site not of consensus but of conflict, an arena in which cooperation is less the product of universal agreement than of repeated negotiation. The ultimate goal of such a politics is the acknowledgement of the community as a heterogeneous polity in which no constituency is rendered invisible and in which every subject is a speaking subject.

The strength of Xhafa’s work lies in what might be called its politics of perception. In a world where the operations of power are often hidden from view, any form of real political resistance must be rendered visible. As Xhafa’s recent gray-on-gray détournement of that ubiquitous catchphrase of post-9/11 paranoia suggests: If you see something, say something.