New York

Haris Epaminonda: Projects 96

Museum of Modern Art

November 17, 2011–February 20, 2012

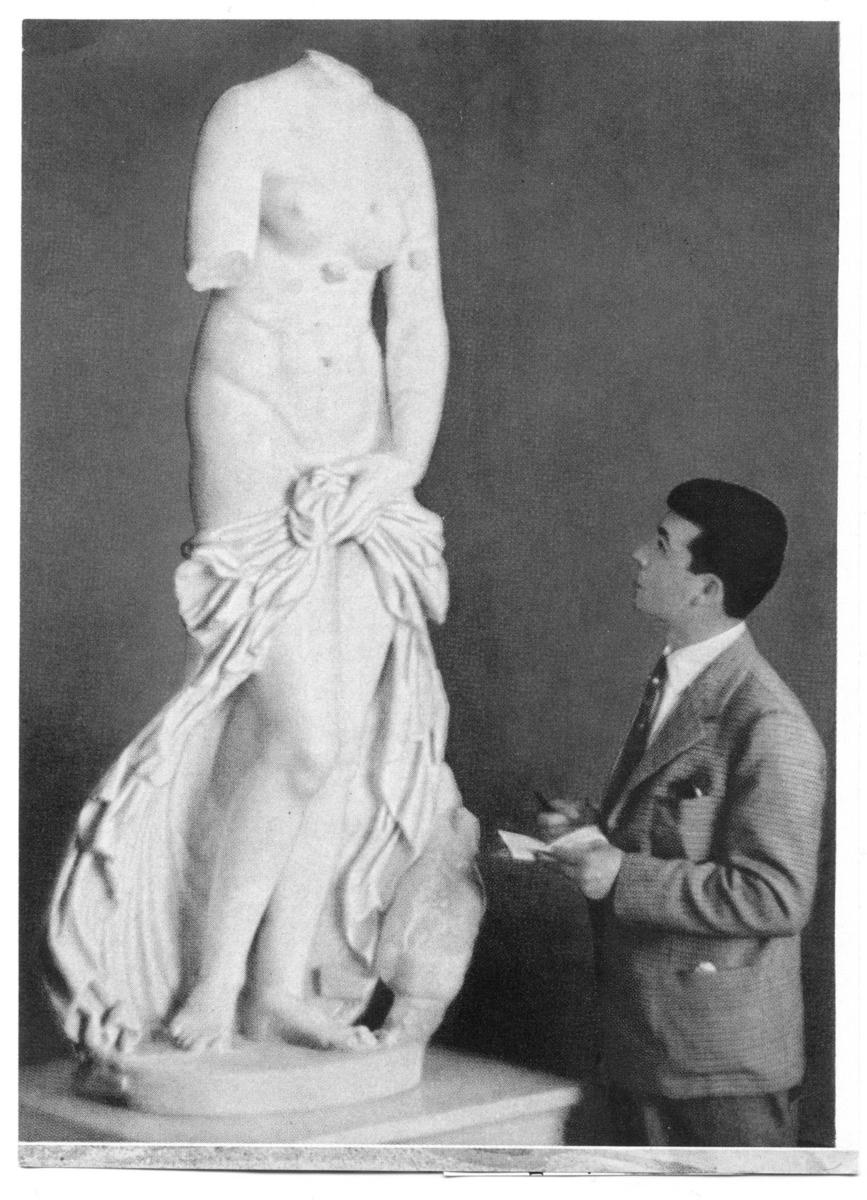

A long-gone museological universe framed in a postcard: amid intarsioed marbles, a lady in a red cashmere sweater, pearl necklace, and earrings, looks up at a massive sculpture of two figures, a lunging male and a defenseless female. It might be a perilous lift in an ice-skating competition, if not for the lion at their feet. The man, bearded and old, clasps the naked young woman to his hip, suspending her in midair as she throws her arms up, alarmed or thrilled. It is Bernini’s Abduction of Persephone at the Galleria Borghese in Rome, and on either side of the sculpture there are medallions set into the wall of the museum with white figures posed in a classical fashion. In a glass cube, another tinted postcard: whoever he is, he is too young to be married to the lady in the red sweater, though he may well be from the same Roman drawing room. He stares up at a headless Venus gathering her robes with one hand held just at the height of her crotch, such that her knees and thighs are revealed and the cloth forms a wide shell around her lower form. He is taking notes, like me. Behind him a sheet of white paper, larger, framed in fine lustrous wood.

The present is a wonderful place if you are patient, and if someone like Haris Epaminonda has collected a few dozen things for you to consider in a space of whiteness, with color and silence. Perhaps you will remember a visit to a museum when you were seven in Greece. Or in Rome, or Detroit, or Berlin, when your mother, or Epaminonda’s mother, was seven. The show fills one with longing for a time when a museum, its walls, floors, and speaking chambers, weren’t jammed with explanations. Epaminonda has recreated the chance encounter between a person looking and the object or place being seen, through the lace or grid of a particular moment in history — one in which the mystery and chasm between different ages, between you and things, tends to be left intact. You see everything as though in a movie, or in the film of memory. Built into the experience is a pre-nostalgia achieved by seemingly minor technical peculiarities — captions without images and images without captions — unthinkable in any museum context now, except possibly in rare treasure houses such as the Archeological Museum of Corfu, which Epaminonda’s show reminded me of, where the unobtrusive low-tech modesty of a setting can be the most effective backdrop for, say, a dazzling Gorgon relief. One might dedicate the Frank Sinatra song “My Funny Valentine,” to the idiosyncratic museum: “Your looks are laughable / Unphotographable / Yet you’re my favorite work of art… Is your figure less than Greek? / Is your mouth a little weak / When you open it to speak? / Are you smart? / But don’t change a hair for me / Not if you care for me.”

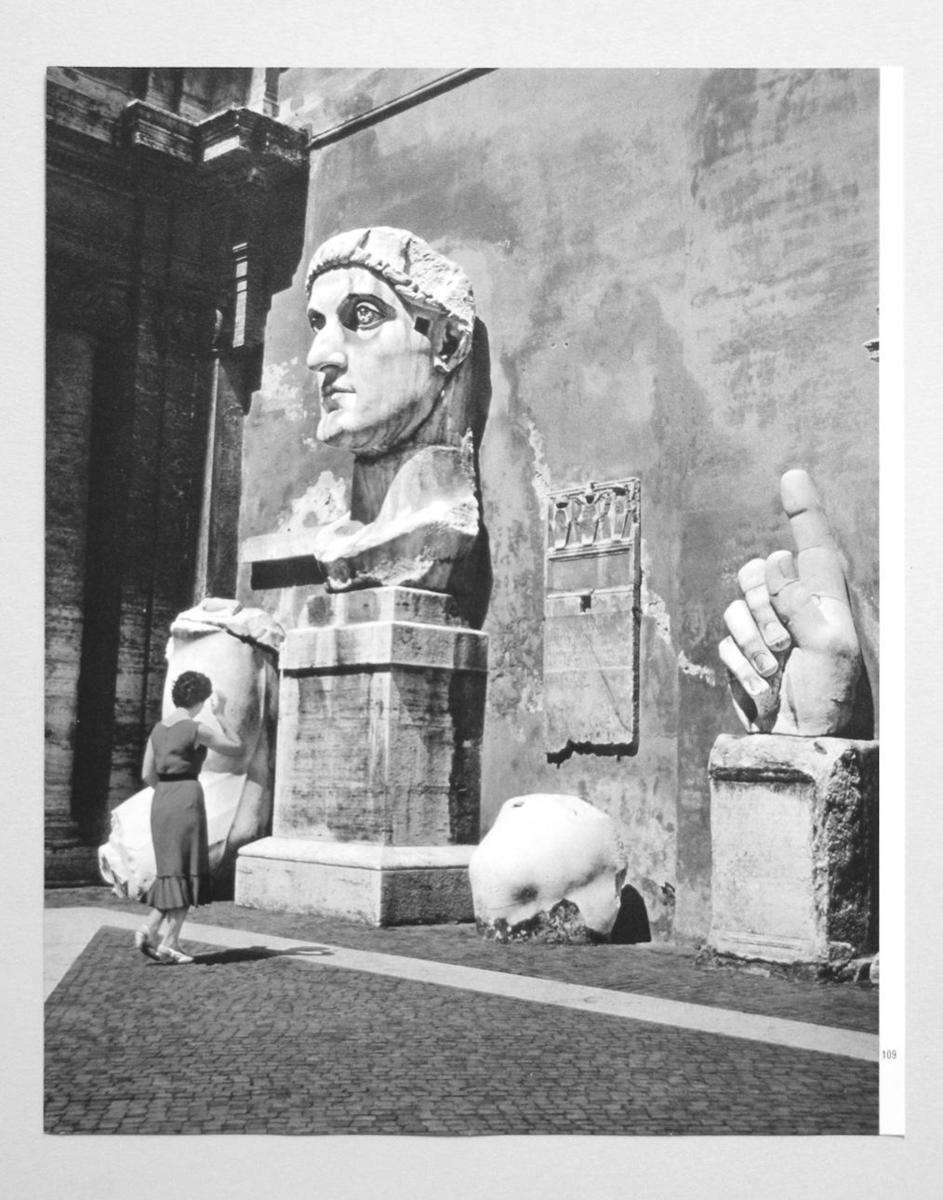

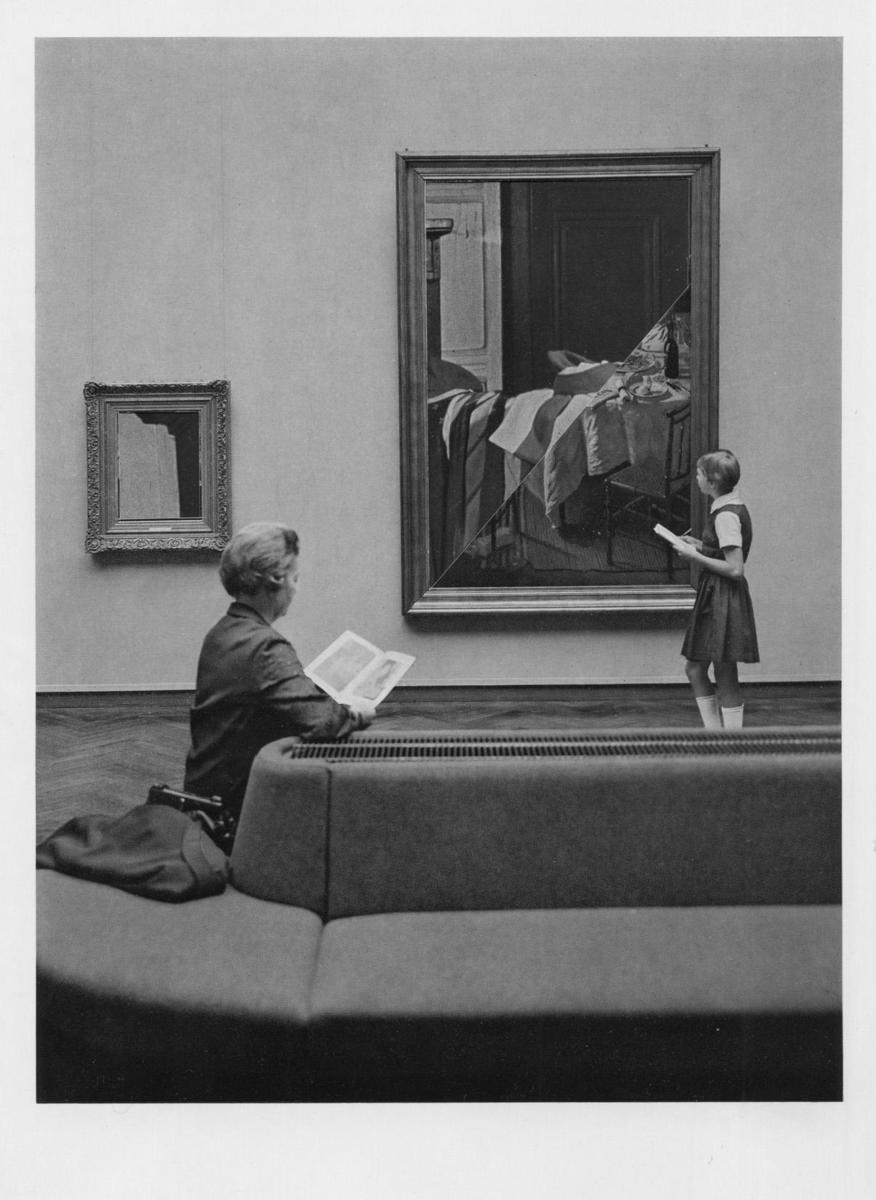

The show unfolds quietly, unobtrusively. There is a black wall. An interruption. A white wall. A passage. On the right, entering the gallery, I’d encountered an image of someone who might have been a friend of my mother’s, in a red dress, gazing at a large marble head. Next to it is the monumental hand of the colossus of Emperor Constantine. Two right hands were found, oddly, each with an upraised index finger as high as the technicolor woman. That is what happens in the subtle regime of viewing Epaminonda imposes: everything is within her museum, an arrangement of artifacts and representations of same, with the atmosphere of a Cabinet of Wonder. Another postcard: more well-to-do figures gazing at art, now amid powder-blue walls. A little girl in a pinafore and white blouse, a lady in a Mercedes-seat-blue suit sitting on a couch. They are looking at a painting diagonally split into two uneven triangles — rather, two paintings joined, an old stove and a draped cloth that hangs down in folds.

Now the space opens out onto a proper gallery whose walls are white with a tall white niche built in. The museum floors are mottled gray, as though waiting for some liquid to be spilled on them that they might then render invisible. On a tallish white plinth is a thunderous turquoise urn. Wavering over a part of its wide belly is a looping brush mark of darker blue, like an acrobatic plane’s signature in the sky. In the white niche, nothing happens.

After an empty corner, a four-sided slim bronze pipe rises from the floor and travels into the wall. On a short octagonal column stands a small celadon green urn. I can see into its shadowy mouth. Above, a smiling warrior. He has perfect Greek features and his hair, long tidy dreadlocks, is draped over his shoulders. Now a short white flight of unclimbable stairs resting against the wall ends beneath a tiny open arch with a small white ceramic vase standing in it, through which I catch a blurred glimpse of the red polo and black hair of a man, a live man, walking by on the other side.

The words “Central Asian Beluchistan Prayer-Carpet” appear beneath an absent image. A tenderly chipped stand, like a screen in a fireplace. An image of columns, the ruins of a temple. Blue sky. On the other side of the arched opening, a huddle of clay pots. An image of broken columns in an overgrown field and a framed absence next to it. A framed black-and-white picture of the interior of a church is on the floor, along with other framed pictures. A large dark urn, mottled by time. The guard in the gallery is from the Dominican Republic; he speaks a little Greek, Portuguese, Japanese, or Italian to visitors, according to their nationality. He loves the work, he tells me. “I live in a Greek community. I want to learn the language.”

I enter the big dark room where there are three screens: one shows palm trees, the air quivering around them; another frames the Acropolis, with rocks in the foreground; the third shows sculptural objects against a red or a green background — images from antiquity, a Chinese vase, a perfume bottle, a statuette of a boy with startled eyes — in reproductions from a more recent antiquity, the 1950s perhaps, against magenta or purple or sea-green backgrounds, everything touchingly drab and real like a place you have already visited and wouldn’t mind going back to. Never the same combination of images — a solution to the dilemmas of editing. One can sit back and absorb every possible alternative without having to choose one, cut out all others, or decide which might be best. And yet the same image differs according to what came before it — the vase after the boy or the boy after the bottle. On the soundtrack, gongs, bells, the subdued snorting of an animal, flutes. The images are grainy. On one screen a book reveals first a flying elephant, then a girl with a high, high forehead and cheeks like little balloons, the pages turned by an unseen hand. From the carpeted floor of the darkened room, I watch the changing images of stills and the unmoving Acropolis in the dancing multicolored specks of air on film, as riveting as the temple itself.