Visionary musician Brian Eno long ago predicted that pop will eat itself — that the relentless appetite for new expressions of the old emotional themes demand that pop will regurgitate every sound, signature and hook in its fifty-year-old repertoire. Yet Eno failed to spot that pop would spend the new millennium dining out on a broadening international cuisine with a distinctly eastern flavor (and we don’t mean the Spice Girls).

Consider the cultural and semiotic blur at work in the following vignette: In 2004, Virginian hip hop producer Tim “Timbaland” Mosely — widely regarded as the world’s most influential hit-maker alongside Los Angeles’s Dr Dre and Pharrell Williams of NER*D — visited London on a promo tour. At his request he was escorted round Southall, the principally Anglo-Indian borough at London’s western edge, by Jay Sean, Rishi Rich and Juggy D, local heroes whose fusion of transatlantic R&B and subcontinental Indian sounds have made them MTV stars in both the UK and India. Tim flexed £3,000 worth of plastic on CDs of Indian desi and bhangra recommended by the trio of crisply-attired rude-bhoys, with a view to widening his palette of sample material.

Resembling absolutely nothing from pop’s back catalogue, Timbaland’s 2001 production “Get UR Freek On” for Missy Elliot blew pop apart. Its ruthlessly spare combination of sitar, dhol and rap sounded unnervingly futuristic and alien, yet simultaneously ancient. “Get UR Freek On” duly left critics open-mouthed, searching ineffectually for comparatives. Meanwhile, precisely no one in the vicinity of a dance floor experienced any uncertainty: It rocked.

The Virginian producer wasn’t working in isolation. In 2002, Dr Dre delivered a global smash with Truth Hurts’ “Addictive,” featuring a sample of the deified Bollywood singer Lata Mangeshkar. In the depths of New York’s hip hop underground, Erick Sermon’s club banger “React” lifted liberally from an unnamed Bollywood sample, both tracks resulted not just in dance floor meltdown but costly legal settlements.

But après Tim, le déluge, because where hip hop producers now lead, pop inevitably follows. Continuing the music business’s standard practice of blanding-out and repackaging the innovations of marginal, generally black musicians, we channel-hop MTV to see pop attempting the dance of the seven veils in a variety of jiggy modes.

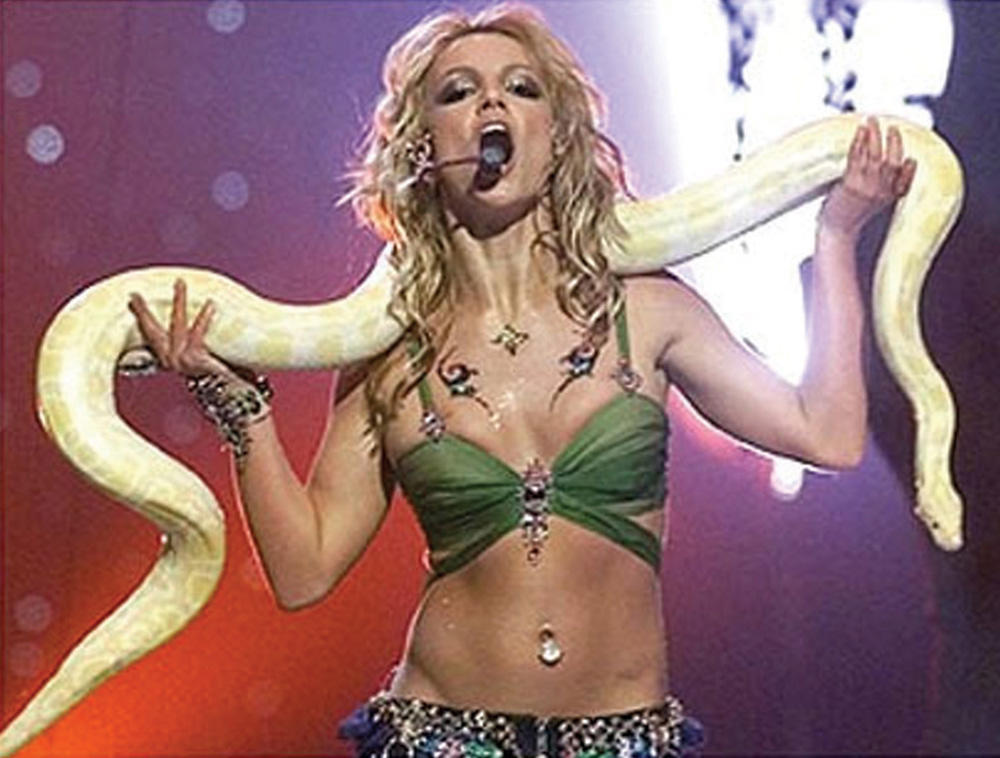

This is often a clear case of stylistic tourism conceptualized in the laboratory of pop demographics — in particular Britney Spears’s sexless belly dance to “I’m A Slave 4 U,” or Holly Valance’s borrowing of the Turkish snake-charm melody of “Simarik” with her “Kiss Kiss.” More marketing maneuvers than genuine fusions, it’s a safe bet Britney’s next outing will have precisely nothing to do with Middle Eastern culture, and it also speaks volumes that the Valance’s career has petered out into obsolescence.

Other instances, like Shakira’s “Eyes Like Yours,” reveal greater depth and substance to the Orientalist flirtation. The singer’s own background — she was born half-Lebanese and grew up in Colombia — describes Latin culture’s ancient proximity to the Moorish Maghreb.

But it’s ultimately far more rewarding to look at the more marginal “weathervane” artists to see where pop’s New Orientalism comes from and what it signifies. The Chemical Brothers, for example, returned to critical favor with a sample from Casablanca Berber singer Najat Aatabou’s “Just Tell Me The Truth” on their “Galvanise” single. What’s clear is that following the flirtation with Indian sounds, the New Orientalism is leading producers further afield, to North Africa and the Middle East, unlocking new thrills from “world music,” the formerly vogue category rendered meaninglessly obsolete in the age of global connectivity.

We know how West African spirituals and swamp blues eventually morphed into Led Zeppelin, Chic and The Strokes once Elvis, Eddie Cochrane and The Beatles had translated it for the benef it of a white western market. Britney’s belly dance is the latest chapter in rock and roll’s primordial but ongoing fusion of western lyrical melody and the African narrative rhythm. It is a signifier of the times. As Led Zep’s Jimmy Page (on “Kashmir”) and George Harrison (“Within You, Without You”) proved long ago, whenever rock and pop run out of ideas the instinct is to turn east towards rhythmic mystique and deeply veiled exoticism.

In 2005, there are other reasons for pop’s widening scope of acquisitive vision. Principally, sample sources for contemporary hip hop and R&B — James Brown, Funkadelic and Rick James — have long since run dry. Popular music is an industry that manufactures novelty, and the clever producer is less concerned with tapping into new markets than forging sounds that distinguish his from his competitors.

Secondly, the dominant music biz powerbases of New York, London and Los Angeles — vanguards of new music precisely because they’re home to sharply contrasting cultural and ethnic mixes — are being challenged by other centers, in particular the dancehall infrastructure of Kingston, Jamaica, where ferocious inter-studio competition to create the hypest “riddim” (instrumental track) ensures that at any moment up to a hundred versions of what’s effectively the same song by different singers are doing the rounds.

Kingston’s recent breakout success was producer Steven “Lenky” Marsden’s “Diwali” riddim: a loop from an obscure desi record that formed the basis of Lumidee’s “Never Leave,” Sean Paul’s “Get Busy” and Wayne Wonder’s “No Letting Go” — all major international hits. Kingston’s affection for Middle Eastern sounds is abundantly apparent in current “hero riddims” like “Egyptian,” “Kasablanca,” “Middle East,” “Bollywood” and “Coolie Dance”; the latter is the basis for Nina Sky’s UK hit “Move Ya Body.” And while there’s no doubting veteran R&B dude R Kelly’s understanding of the appeal of the “Baghdad” riddim he used on “Snake,” there’s also the suspicion his affinity with the Middle East is roughly as well developed as his sense of sexual etiquette.

Nevertheless, the East-West trade in sounds signatures also works both ways, opening up new markets, fusions and scenes. Would “Mundian Te Bach Ke” — the Euro-wide desi/hip hop hit sampling the theme from “Knight Rider” — have been such a smash if its author, Punjabi MC, had named himself Coventry MC in honor of his UK home rather than his cultural rooting? “We try to make our music more appealing to non-Asians,” says British-born Juggy “Jagwinder Dhaliwal” D. “Punjabi music has been around for years, but it took Dre and Timbaland to use influences before it became cool. That gave us the opportunity to say, ‘we’ve been doing this for years.’ Hence a number twelve last year, a crossover Punjabi/R&B track. And people loved it.”

“People from Iran spread through to north India and there’s a degree of spread in the music,” adds DJ Nihal, the host of BBC Radio 1’s groundbreaking evening show with a wide-open brief to cover the best in Anglo-Asian and Middle Eastern fusions. “We will play Arabic beats on our show, and we were approached recently to do Anglo-Asian mixes of Rachid Taha. There are very close ties between Rai and Bhangra — they’re both folk music which deal with very similar themes.” Other outposts beneath the global pop radar continue to innovate, and the “Diwali” experience reveals how fusions of Rai and hip hop in France, such as Cheb Mami’s “Parisien Du Nord,” or traditional Turkish music and house in Germany like MC Sultan’s “Der Bauch,” have the potential to hit big.

Being cyclical, faddish and disposable is a necessary element of pop’s appeal, and it’s arguably a matter of time before not just big, but also credible hits with a Middle Eastern root enter the MTV pop stratosphere. In London today, the smart money is on Rouge — an all-girl trio with Arabic, Iranian and Anglo-Indian membership — and on MIA, twenty-three-year-old Sri Lankan Mia Arulpragasm, whose fusion of Breakbeats, Dancehall, Desi, Hip hop and Brazilian “Baile funk” could only have happened in London, but equally could not exist without a cross-cultural mishmash between New York, Rio and Colombo.

It may ultimately be pointless attaching any kind of Orientalist dialectic to pop music. Unlike literature or conceptual art, pop music is meant to be danced to rather than deconstructed. It really is that simple. All it asks you to do is leave your mind on the bookshelf for three minutes and believe. For now, as music’s tectonic plates shift and grind into new shapes and sounds, it is succeeding spectacularly.