Monira Al Qadiri is a visual artist and promulgator of seriously mad visions of petrochemical grandeur, identity, and delusion. In the 2000s, she did a PhD in intermedia art at Tokyo University of the Arts, where her research on the aesthetics of Middle Eastern melancholy generated work on “The Beautiful Sadness” and ‘The Tragedy of Self.’ Today her sculpture, films, and performances express an approach to gender, heritage, and time that is at once playfully conceptual and conceptually playful. With her sister, the artist and musician Fatima Al Qadiri, she belongs to the collective art entity GCC. Her most recent exhibition, ‘The Craft’ (at Gasworks, London and Sursock Museum, Beirut), explores Cold War culture’s fiery twilight.

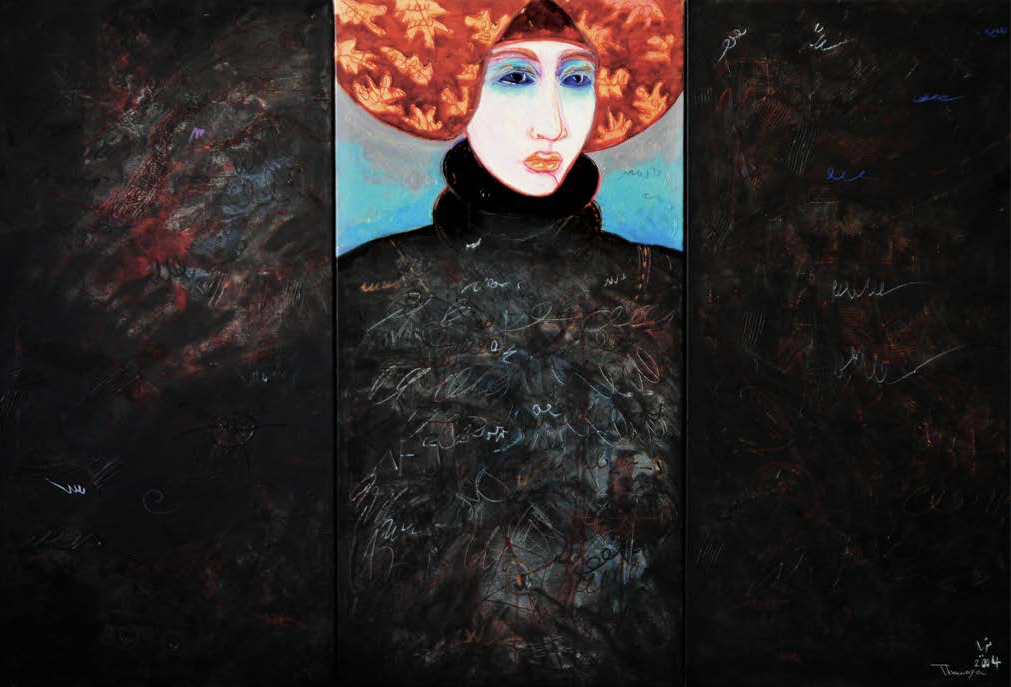

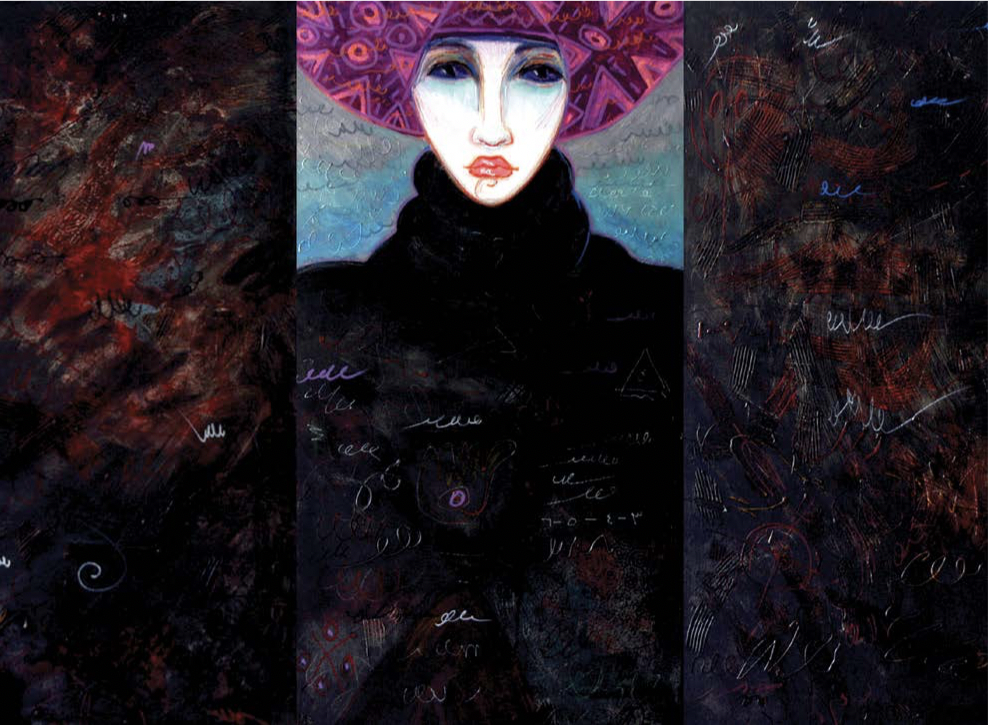

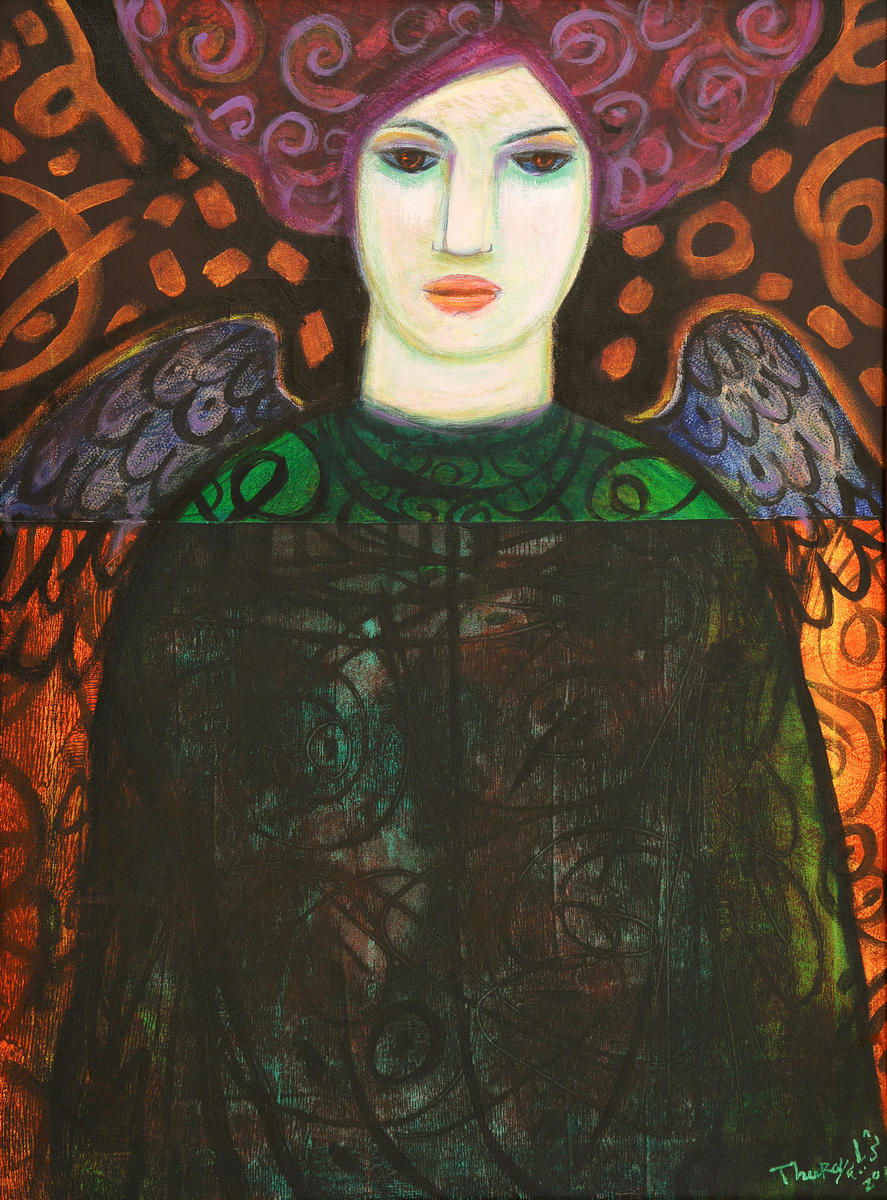

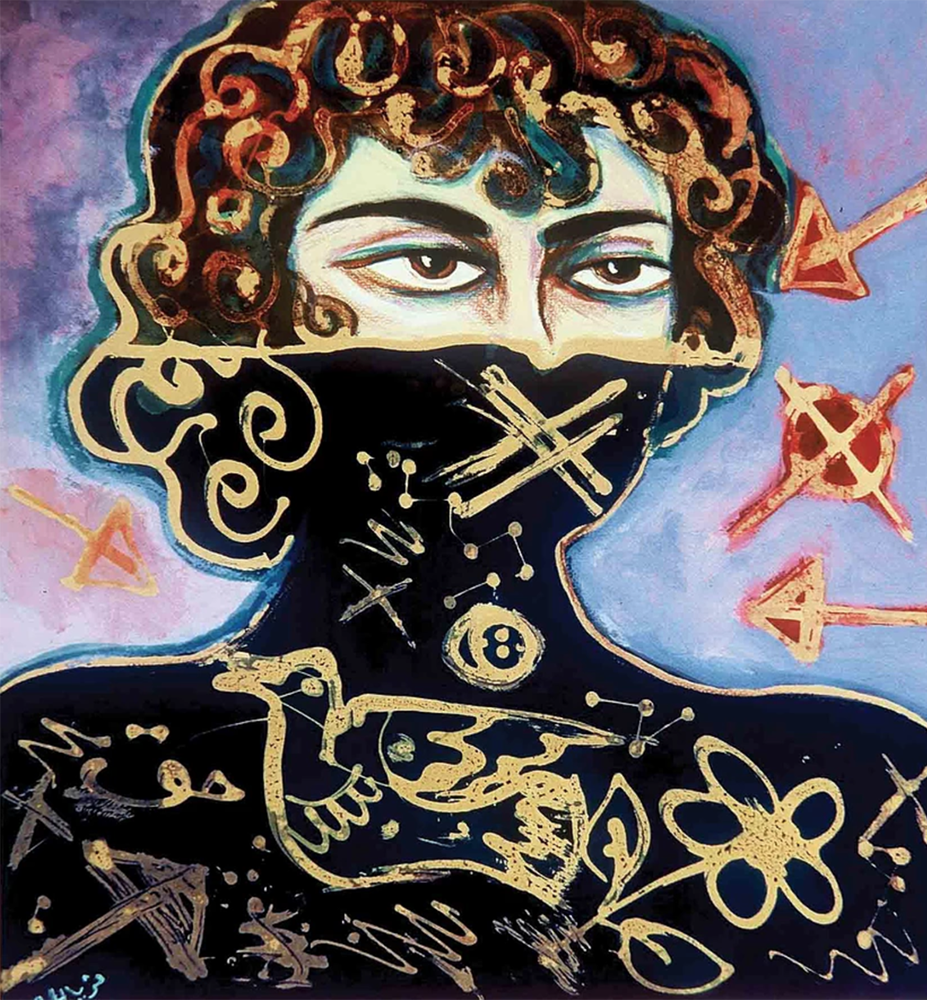

Monira’s mother, Thuraya Al-Baqsami, is also a visual artist, with a career that spans five decades and three continents. Educated in Cairo and Moscow, where she obtained a Masters in illustration from the Surikov Institute, her work has long engaged with poetics and politics, feminism and the feminine. Al-Baqsami is also a journalist, activist, and fiction writer whose publications include novels, children’s books, and short story collections, including, most recently, A Fish Riding a Bicycle (2015).

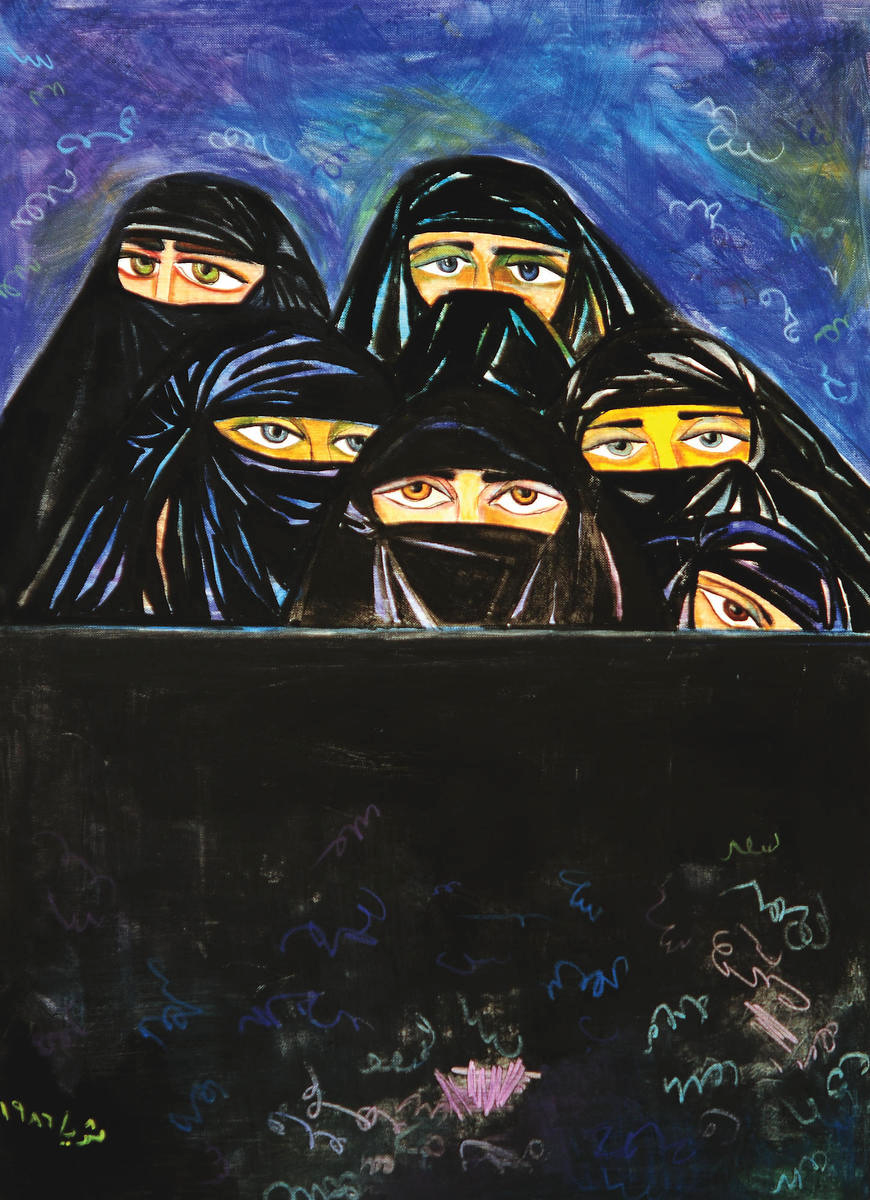

In October 2017, the Sharjah Art Museum presented ‘Lasting Impressions,’ the largest-to-date exhibition of Al-Baqsami’s works, curated by her daughter Monira.

In late January of this year, at Bidoun’s behest, the two of them sat down together to discuss their shared and discordant interests, including communist Russia, capitalist Japan, the female form, and life during wartime.

Monira Al Qadiri: Recently I made this film, The Craft (2017), in which you were secretly conspiring with aliens behind our backs — behind the backs of your children, that is. It is fiction, of course, although Fatima and I actually dreamed this when we were kids. And you’ve always been painting turquoise-green people in your work. We grew up surrounded by these characters, and these characters do resemble aliens some of the time. And all of this had definite consequences for our future development. [Laughs] So I wanted to start by asking you to talk about where all this came from — about your real connections with this world of science fiction.

Thuraya Al-Baqsami: I grew up in the 1950s and 60s, so the space race was a big deal for us. I remember watching the moon landing on TV at home — it was awe-inspiring. But I should say that when I was younger, I believed that I was visited by spaceships.

MAQ: By UFOs?!

TAB: I don’t know if this was real or my eyes playing tricks on me — and I mean, it was all over the news at the time, these stories of spaceships and abductions — but one night when I was sitting with my neighbor on the roof of our house, studying for exams, we both saw a spaceship hovering right above us.

MAQ: What did it look like?

TAB: It was round, with lots of lights. It spun and spun and disappeared. Then, on another occasion, we were at a chalet by the sea, sitting on the beach, when we saw another one spin around in the sky and then disappear. It was almost a dream come true!

MAQ: You used to dream about UFOs?

TAB: I daydreamed about them all the time. Remember, I was at an adolescent age, so I used to always dream that a spaceship would come down and abduct me to the planet Mars.

MAQ: Mom! [Laughs]

TAB: But I wanted to go. In the dream, after the green man took me back to his planet, I met the Martian prince, who I would marry and make a family with. Then when I came back to Earth, everybody would discover that I was now a Martian princess.

MAQ: A princess by marriage. Okay, so this prince — what did he look like? I am picturing Alain Delon, or…?

TAB: No, I imagined him more like Omar Sharif or Abdel Halim Hafez. Or Cliff Richard.

MAQ: Cliff Richard?!

TAB: Oh yes, he was very handsome in Summer Holiday.

MAQ: I’ve never heard you mention him before. What about Iranian pop stars, like Vigen?

TAB: No, they weren’t part of my agenda at the time. There weren’t any Iranian films in Kuwait. I do remember seeing Indian movies, though. I loved Mother India.

MAQ: Did you see a lot of movies growing up?

TAB: I used to go to the movies a lot with my sisters and brothers. Anyway, the movie stars I liked at the time were mostly the Egyptians, Cliff Richard. From the Beatles, I liked Paul.

MAQ: And your Martian prince looked like a movie star.

TAB: Yes… or sometimes like the boy next door, who I used to fancy. Though I only liked him because he played tennis.

MAQ: Oh why!? Because it was posh?

TAB: Not really, no. It was because when I would come back from school on the bus I’d always see him in his short shorts. He was tall and handsome, and he held a tennis racket in his hand — I was really attracted to that demeanor. [Laughs] So much so that I bought my own racket and I would play alone against the wall behind our garden all day. Sometimes I’d go outside with my racket and short tennis shorts… I wanted him to notice that there was someone else in our neighborhood who played tennis.

MAQ: Didn’t you write a short story about the Martian prince when you were fifteen?

TAB: Yes. It was called “The Bride of Mars.” At the time there was a weekly women’s magazine called Usrati (My Family) that had a section for letters from readers. I sent them an article about men with multiple wives — my relative had married a woman whose uncle had married four women simultaneously, and I saw up close how much they hated each other. They were fighting all the time, and it really affected me. They published it. I sent them more articles, which they published, as well. Since my writing was getting good reviews, I felt encouraged to send them my Martian story. I’d written it out carefully in longhand — it took up a whole notebook. I was so excited. At the time I was weak in Arabic grammar and syntax in general, but I felt that I could be a good writer.

MAQ: You are a great writer.

TAB: So I sent them the story. And I waited. And then finally the editor wrote back to say that I had a good imagination, but that my Arabic was so poor that Sibawayh, the great systematizer of Arabic grammar, was turning in his grave. And then he published his letter to me in the magazine!

MAQ: Oh no! You must have been shocked.

TAB: Of course! I cried so much. I asked him to return my notebook, but he never did. I wish I could read it now and discover all the linguistic crimes I committed that made the guy turn in his grave.

MAQ: I wish I could read that now, too. I love how space was a source of inspiration for you, the way it has been for me, as well.

TAB: It was so inspiring. Even in my paintings at the time, I was drawing these aliens. They were very thin, like skeletons, with spiky hair and big eyes, walking on the moon. These were my obsessions.

MAQ: We have two of those paintings on old photographic slides at home — one with two people looking up at a rocket launch, and another with a woman and a man walking on what looks like another planet.

TAB: That’s me and my habibi.

MAQ: Your Martian habibi! [Laughs]

TAB: You know, in my life I didn’t have any love stories or relationships. At the time, our society didn’t allow romance at all. The only thing left for me was to dream and fantasize.

MAQ: But your need to run away from here, where did that come from? I know I felt an intense desire to escape this place, growing up in Kuwait.

TAB: I wasn’t really thinking about running away. I just wanted to have a romantic experience. I was a daydreamer. I was living inside a dream all the time.

MAQ: I was an avid daydreamer, too.

TAB: I wanted a love like the one I saw in the movies — someone to caress and hug me. This imaginary boyfriend, who was a collage of all the stars I liked at the time, was my escape. I wanted to find a warm bosom somewhere.

MAQ: And the bosom you found in the end was my father’s. [Laughs] Who did look a little bit like Omar Sharif! In any case, I find it interesting that there are so few images of men in your work. I can think of maybe a dozen paintings with male figures, including your habibi. Why is that?

TAB: Well, there was a period where I was painting men all the time. When I was a student in Moscow, my professor just disliked the female form in general. He never hired female models — they didn’t keep their appointments, he claimed — so for three years all the models we painted were men. Particular kinds of men — I tried drawing my husband once and the professor said he wasn’t interesting enough, not “model material.” [Laughter] And after that whole experience I was so bored and frankly traumatized, I felt as if I was suffering whenever I had to paint men. I vowed never to do it again.

MAQ: Where are those paintings? I feel like I’ve never seen them.

TAB: You wouldn’t have. I didn’t bring them back with us. I gave them away as gifts.

MAQ: You’re such a hoarder. You keep everything! I wonder, is this part of why you hate painting people from real life? Most of your subjects are imaginary…

TAB: Well, sometimes when I see a face and I feel affected by it, it appears in a painting at some point later. Or earlier — strangely enough, I made paintings when I was younger that turned out to look like my daughter Ghadir when she was grown up.

MAQ: Yes! I’ve noticed that. It’s crazy.

TAB: Starting from when I was fifteen — long before I had a child. How did I paint this person who looks so much like my daughter!? It’s a mystery. I always liked to paint this one girl with big eyes and long curly hair. It was as if I could see the future. Though as you know my sixth sense is very strong — maybe it works retroactively.

MAQ: You were haunted by your future.

TAB: I should say though that it’s not just that I found it painful to paint men — I’ve always liked painting women. I see in women beautiful aesthetic features that are just not visually apparent to me in men. The curves in her body, her psychological makeup, her expressions… I find it impossible to see these things in men. A man is like a wall. He’s flat. He’s not interesting.

MAQ: He doesn’t have curves! [Laughs]

TAB: Yes, that’s important. For me women are not just shapes, they are also a theme. For a long time, I was — and still am — a feminist. I was protesting for women’s rights in my life and in my work, talking about the oppression of women, discussing women’s issues like divorce and separation, and so on. So I see the drama that Arab and Middle Eastern women face in my own life and in the lives of people around me, and it enthralls me. There are so many things women are not supposed to talk about. So many taboos! Everything she says and does is judged. So I would vent my frustrations by exploring the female form.

MAQ: Your work is very political. Sometimes subtly so.

TAB: During the war, the woman was the national emblem, the symbol of Kuwait. Woman can signify so many diverse subjects — I showed her as a mother, as a lover, as an oppressed figure, as an abandoned body… For example: in my painting, Flying Desire (1985), an abandoned woman seeks love from a man who is frozen in front of her like a statue. He is punishing her with his silence. In a lot of my work I show the push and pull of desire between men and women, the aversion as well. Some of these one experiences in one’s own life or sees in the lives of others.

MAQ: So the women represent you at times and other people at times, but also fictional or imaginary characters?

TAB: Yes… but the matter of fact is that ninety percent of the time, she represents me.

MAQ: Oh really? I didn’t know that.

TAB: It’s true in my writings, as well. I can’t write honestly or paint honestly if that expression doesn’t represent me in some way. My philosophy is: Be honest with your creation. Show us something you’ve experienced with honesty. It’s not narcissism; for me it represents the real truth of the artist.

MAQ: I like the idea of describing one’s work as a self-portrait, even when you borrow fictional characters to represent yourself. The soul is yours. I feel the same way about my practice — those sculptures of drill bits that I make — the monumental one in Alien Technology (2014), as well as the smaller ones in the Spectrum series (2016) — are really self-portraits. They evoke my cultural heritage as a child of the oil… [Laughs]

TAB: I know that those works are very personal — about family history, the gulf between you and your generation and your grandfather, who was a singer on pearl-diving boats.

MAQ: I have to admit, though, that I felt oppressed by all your women. Growing up, it was women, women, everywhere. We were three sisters with no brothers, and all your paintings, and both you and my father were so very much into women’s rights — we had an overdose of women in the household. [Laughs] Our whole lives revolved around them. Such that this thing called “a man” became very exotic. I wanted to get to know him. For many years, I even wanted to become him! I’ve regained some of my lost femininity since then, but I confess that still find masculinity to be more interesting. And I still find men to be beautiful, from my point of view.

TAB: To be honest, I was worried about you when you were younger, but I left you to do what you felt like doing.

MAQ: You were probably the most liberal mother in all Kuwait! As your daughters, we were able to exercise our freedoms completely, without any restrictions. This was a good thing for us, but people in the outside world thought we were crazy. And that you were crazy, to let your kids do whatever they wanted in this super-liberal atmosphere. Didn’t you find yourself pressured to conform, sometimes? How did you become such a free spirit?

TAB: It’s because I came from a liberal family, myself. My father and mother gave us our full freedoms. They never asked us where we went or who we saw or talked to. They let us wear whatever we wanted, go wherever we wanted… so we wore miniskirts and went to concerts and did everything we liked. We would do sleep-overs and they never said anything.

MAQ: This must have been very unusual, no?

TAB: I mean, it should also be said that my mother was very young and she had six children, so there was no way she could supervise every little thing we were getting up to. And my father was tending to his business all day, so by the time he got back from work he was too tired to lecture anybody on anything. The nice thing about him was that he was a great storyteller.

But still, most of Kuwaiti society — let’s say sixty or seventy percent — were living a life like this at the time. In the 1960s and 70s, Kuwait had the most liberal population in the region. Bahrain was pretty good, too. Oman.

MAQ: I remember you telling me once about an Omani couple who lived near you when you were growing up, two married men, and that that was kind of normal at the time.

TAB: Yes. I was visiting this family once and their neighbors were two Omani men who lived together as a couple, one dressed like a woman, the other like a man. I was extremely curious about the world and so I asked my friends what was happening, and they told me this was normal in Omani society. Basra was famous for this kind of thing, too. Effeminate men were called farkh (chick). Sometimes they would accompany musical groups as dancers or participate in zar (exorcism) ceremonies. They would dance at weddings. This was all over the region — it had been there for centuries. Even lesbianism had been pretty common in palaces and courts. People didn’t see homosexuality as this ugly aberration, they saw it as part of human nature. People would often be seen in romantic situations with the same gender.

MAQ: Things are so much worse now.

TAB: I remember going to a wedding in Iraq when I was younger, in the city of Karbala, and there was a famous singer who had this green cloth tied around her head, which was a signal that she didn’t have a girlfriend and she was on the lookout for one. People thought this was okay. Everybody was much more open than they are now.

MAQ: So what happened? Because I feel that ideas about gender and the segregation of men and women in our generation were much, much harsher than it was in yours.

TAB: Absolutely, yes. Nowadays people get thrown straight into prison. I can pinpoint the change to the early 1980s.

MAQ: The years of the Islamic awakening.

TAB: That’s right.

MAQ: Which you managed to miss! It must have been so shocking, when you returned home after so many years abroad — in Cairo, Moscow, Kinshasa, and Dakar — to discover that your family had become extremely religious?

TAB: It’s true. When I left in 1972, everyone was in miniskirts, and when I came back in 1984 there was no skin showing at all! It was all fabric from head-to-toe. The women were like wrapped mummies walking around.

MAQ: Was that hard for you? Were you criticized for not changing along with everyone else?

TAB: Of course. I became the black ugly duckling, with her hair still out and everything. The black sheep in the family. I’m the only one who didn’t cover.

MAQ: Maybe you were lucky to have been away while everyone else was becoming more conservative.

TAB: I was lucky to miss that. But I was also lucky to have a husband who didn’t want me to be like that. He told me, “I would never accept it if you did that to yourself.”

MAQ: Did you ever, even once, fancy the idea of becoming conservative?

TAB: No way! Whenever it’s forty degrees Celsius outside and I imagine myself covered in fabric… it’s impossible to imagine doing that to myself. Absolutely impossible.

MAQ: [Laughs] You’re always so practical!

TAB: Maybe in Moscow, when it’s forty below. [Laughs] Of course, at the time I was also young and in good shape. I refused the veil because I wanted to show my beauty to the world. I’m an artist — why should I hide it all behind a ton of fabric? Like a walking barrel or something.

MAQ: Your femininity is very important to you. Why is that?

TAB: Femininity is a woman’s soul. I believe that when a woman loses that aura, a part of her dies. Even if she’s eighty years old, if she still exudes her femininity, that gives her power — it gives her strength. It’s not about makeup or a nice hairdo or what she’s wearing, it’s something deep inside, like a… green space. I feel like there’s a forest inside me, full of vegetation. Like a bowl of tabbouleh.

MAQ: [Laughs]

TAB: It’s this feeling of greenery that keeps me going. Even though I’m sixty-seven years old, I still feel like I’m fifteen. I don’t feel my age. Of course, there’s been a lot of life experiences, but most of the time I still feel like that mischievous fifteen-year-old girl, holding the tennis racket and waiting for her neighbor to show up.

MAQ: I wanted to ask you about that period you spent in the USSR. You were there for quite a while …

TAB: Seven years.

MAB: Right. I guess I wonder how formative it might have been for you? I know of course that your husband — my father — was a communist at the time…

TAB: Well, he wasn’t a real communist. He loved the ideology behind it, but he never, for example, belonged to a political party.

MAQ: But political parties were illegal in Kuwait, anyway.

TAB: During the time that we were in Moscow, all the communist student bodies were there. This was when the Saudi communist party was announced. The Bahraini communist party was there. Of course, the Syrians and the Lebanese were allowed to form parties anyway, so it was normal for them. The Palestinians were there, as was the Rakah party from Israel. But it’s true, there wasn’t a formal Kuwaiti communist party. They called themselves progressives and were quite flexible: one day they would like Mao, one day Marx, one day Ho Chi Minh, one day Salvador Allende. They were fascinated by all of these icons at once.

MAQ: So it seems fair to say at least that he had very communist leanings? [Laughs] Like a lot of people at the time. Of course, as your daughter I remember the great story of how, when my father was courting you, he sent you a book which you initially mistook for a romance novel…

TAB: Das Kapital. It was a total disaster. I was a university student in Cairo at the time, and he was the head of the student union in Kuwait. We met when he came to oversee the elections for the Kuwaiti student union chapter in Cairo. I was running for the position, and he let me win, of course. [Laughs] I mean, we were both attracted to each other, but we were not expressing it at all. So then when he gave me the book, I was ecstatic — I spent the whole night reading through it, and I didn’t understand a word. The next time I saw him, I asked him to explain what the book was about, and he told me, “This is so I can educate you, as my comrade.” I couldn’t believe it. Where’s the love? He said, “You’re looking for a romance novel?” So then he gave me a copy of Gibran Khalil Gibran. And even that… there just wasn’t enough romance in it. Maybe he should have given me Nizar Qabbani or something.

MAQ: [Laughs] So then you fell in love. How did he convince you to drop everything in your life and follow him to Moscow?

TAB: Well, as I was telling you, ever since my teenage years I had been looking for love. But I was very shy. If I liked someone, I would rather kill myself than tell them. In my daydream I would marry them one day and then divorce them the next and marry someone else. I was very funny that way. And I was still very young at the time.

MAQ: You should have been a comedian. Even your idea of romance is funny.

TAB: So then your father came along and he was the only person who knew how to get to me. He made me feel like a woman. He was very good with words and he chatted me up the right way. He buried me with all the letters he sent!

MAQ: What did he write? Were they love letters?

TAB: They were love letters… but written in a very Marxist language. Always references to comrades; very communist overtones. But anyway, he was my prince in shining armor. He told me that he loved me. That’s how I saw it.

MAQ: And then he abducted you to Russia. [Laughs]

TAB: Honestly, I was prepared to follow him to hell if he asked me to. [Laughter] I’d finally found my love, and that was all I cared about.

MAQ: So what was it like when you arrived in Moscow? What were your first impressions?

TAB: That first day in Moscow I cried like crazy the whole day. They were going to separate us. There was no space in the married dorms, so I was supposed to live with a female Iraqi student while he lived with an Afghan male student, and we were only allowed to see each other on the weekends. He would have to make an appointment with the Afghani guy to leave the room. I said, “I didn’t leave my life so I could come and live here alone in this frozen hell and see my husband once a week.”

MAQ: [Laughs] So he did ask you to go to hell…

TAB: So then the housing committee came back and told us that we were in luck — an Iraqi couple had been arrested by Saddam Hussein’s forces, so we could have their room.

MAQ: Wow, that’s dark!

TAB: Yes, truly. But we were happy we could live together.

MAQ: Was it difficult for you to suddenly find yourself in this heavily communist milieu? My father was extremely into it and had read every book on the topic, I know. But you were a total outsider. How did you get by? Did you become a believer at some point? I mean, seven years is a long time. You had to at least pretend that you were interested, didn’t you?

TAB: It was impossible for me to be a real follower. I was only interested in the man — my husband. But at university, we had to do exams in dialectical materialism, communist theory. So I did have to perform all the time. But then my fake performances were so good, I would get the best grades without reading the books at all.

MAQ: [Laughs] Of course you did. I mean, you’re a great poet.

TAB: I made up so many convincing stories! They couldn’t believe that a girl from such a deeply capitalist country as Kuwait could say these things. I still remember my communist theory exams, which were very important — you basically weren’t allowed to graduate without passing them — I was standing there in front of these six ancient communist dinosaurs and I said, “Poor communism, capitalism always tries to wash its bones away, but its bones are hard, like a dinosaur’s — they can withstand anything.” And they said bravo! and gave me the highest grade.

MAQ: I can’t believe you got away with it. [Laughs]

TAB: But — and this was what I wanted to express in my novel, In the Time of the Red Crescent — most of the students who went to Moscow believing in communism returned home as ultra-capitalists.

MAQ: Like my father…

TAB: Yes.

MAQ: You know, I had the opposite experience. Living in Japan for ten years — such a hyper-capitalist society — I became so anti-capitalist you couldn’t believe. Capitalism was so ugly and harsh on people; I started thinking that communism was so much more beautiful and ethical. But then your experience living in a communist country was not always so beautiful. There were so many restrictions — so many ways to get into trouble, if not arrested. As a woman, especially.

TAB: As a pregnant woman. My experience of giving birth in Moscow was very severe. Once I entered the hospital, I was not allowed to have contact with any person from the outside, not even my own husband. We were forced to write letters to each other. He couldn’t see the baby; it wasn’t allowed, because he might bring microbes in, according to them. I was forced to remove my shoes, clothes, everything that was from “outside” and not sterile. Then at night they would take our slippers away so that we wouldn’t try to jump out the window and escape from the hospital.

MAQ: It sounds like a prison.

TAB: Exactly! I was hungry all the time. The food they gave us was ugly hospital food. One day I managed to get word to my husband to send me a chicken. Just cook a chicken any way he could and stuff the pieces into an envelope, scribble some Arabic on it, and tell the hospital administration that this package had been mailed to me from Kuwait. And it worked! When they brought me the package, I waited for the nurses to leave before I tore it open. It was really badly cooked, but I felt like a lion devouring a gazelle!

MAQ: [Laughs] My father is a terrible cook.

TAB: It’s true. He can only really make tea and wash dishes. [Laughs] Of course, I was a bad cook, too. Even so, the other patients in the ward were envious of me. I told them that my mother had sent me a chicken from Kuwait, and they said, “Next time, have her send you a turkey so there’s enough for all of us.”

MAQ: [Laughs] That’s so funny. But it sounds awful.

TAB: It was very harsh. They wouldn’t let me use a pen and paper! I wanted to write and to draw but they took everything away.

MAQ: Why would they do that? Did they think you were going to kill yourself with a pen?

TAB: I have no idea! They would just bring the baby over to us to breastfeed and then take it back. We weren’t allowed to sit with our own babies. Can you imagine?

MAQ: How did you pass the time?

TAB: Well, so there was this cleaning medicine, like mercurochrome but green. One day I took a bottle and started drawing all over my body with it — I used a cotton bud and I drew trees and birds and all sorts of things, from top to bottom. Only afterward did I find out that it didn’t wash off. [Laughs] So then when it was time for my medical checkup, I was trying to cover myself up. The doctor and I were both pulling at the covers — he wanted to know what I was hiding. When he finally pulled it off he shouted, “What is this?” I told him that I was an artist, and that if he didn’t give me a pen and paper I was going to do this same thing to all the other patients in the ward. I threatened to turn all the women into my canvas!

MAQ: They must have thought you’d completely lost your mind!

TAB: The very next day they brought me pens and paper and begged me not to paint on anybody else!

MAQ: [Laughs] And then when they finally let you out, they put you in a camp in the middle of nowhere, right?

TAB: That was actually before I gave birth. The doctor insisted that my baby wasn’t getting enough oxygen. She said I had to go to a pregnant women’s retreat in a forest so that the baby could get more fresh air. Mind you, it was forty below zero outside. This camp had been used by the astronaut Valentina Tereshkova, but I wasn’t planning to give birth to an astronaut! Why should I go?

MAQ: [Laughs] Where was this camp again? Siberia?

TAB: No, it was a forest outside of Moscow, quite far out from the city. In the middle of the forest there was this health center, and the building was made of wood. And the guy in charge of the heating was always drunk on vodka and fast asleep. So, the heating wasn’t working, it’s minus forty outside… I would sleep in my full winter getup — my shoes, hat, and fur coat — but I still froze and shivered all night long. The food was terrible, no salt or anything. But that was fine — I could handle all of that, but the thing I couldn’t stand was that they insisted on taking me out to walk in the forest for three hours every day so the baby could “get oxygen.”

MAQ: You were going to die of cold!

TAB: I was crying. I tried to tell them that I came from the desert, that I’m not used to this kind of weather. I can’t walk in the forest for thirty minutes, let alone three hours. They were not sympathetic. At one point they took me to another part of the forest and showed me something they called marji, where old people would dunk themselves in ice water after a sauna. It was supposed to be a joke, I guess — they said, “If you don’t stop your nagging, we’ll dunk you into this ice water, too.” I was so upset that later that night that I collected my things and ran away in the middle of the night like a criminal. I found my way to the train and went back to the dorm in Moscow. A few hours later, the police showed up. They thought I’d gotten lost in the forest and some wolf had eaten me.

MAQ: [Laughs] Oh, dear. Were there many women in Moscow with you?

TAB: There were some. The Iraqi artist Afifa Alelby was studying with me. But — this is funny, actually — I had become the head of the Kuwaiti student union in Moscow while I was pregnant with your sister Ghadir, my first child, and at one point I participated in a women’s youth conference in Kazakhstan, which was part of the Soviet Union then. All of the other members of the union were men. And your father was my secretary.

MAQ: [Laughs] Magnificent! What were the Arab students in Moscow in the 1970s like?

TAB: It was a mix of people, really. The first year we were all together in the same place — the foundational language course was in its own building, part of it classrooms and the other part the dormitory. The students were from all over. Some had been sent by their political parties, some by their governments. The government-sponsored students basically worked as spies, gathering intelligence on the party-affiliated students. They would write reports for their embassies, so that when a guy they were spying on went back to his country, he’d get arrested on arrival. At the time the north Yemenis were spying on the south Yemenis, while the Syrian Baathists were spying on the Syrian communists. Every faction would be spying on the other one.

MAQ: So the intelligence agents and communists were all mixed together.

TAB: We had military people, too. [Laughs] I mean, it was a foundational language institute, so there were people from all different kinds of backgrounds. It was a funny situation.

MAQ: I guess it was clear who was a spy and who wasn’t, then?

TAB: Oh sure, we all knew who was doing what. The government students were tujjar shanta.

MAQ: “Bag merchants”? What does that mean?

TAB: Their bedrooms were like supermarkets. They would sell shaving kits, toothpaste, blue jeans — anything that wasn’t available in communist Russia. We were mostly interested in the condoms. Russian condoms were such bad quality! They always had holes in them. The Arab married couples would get pregnant quickly from using the bad Russian condoms. These people made rockets fly into space, but they couldn’t make a reliable condom!

MAQ: [Laughs] Amazing.

TAB: There were so many contradictions. Arab students got drunk a lot. They acted like they’d never seen the stuff before, partying until all hours. And of course, so much was lost in translation. At the end of the year they asked all of us to sing a national song at this event. The Syrians were a big group — ten students who were very tall, just mustachioed and really macho — and they started singing their national anthem, “Biladi, biladi, biladi” (my country). Suddenly the Russians stood up in protest! It turns out that biladi meant “prostitute” in Russian, so it was as if they were singing “whore, whore, whore.”

MAQ: [Laughs] Actually, I wanted to ask you about this question of translation and miscommunication. How did you end up getting integrated into Russian society? Was it difficult to get people to accept you? I know when I lived in Japan, I felt like an extraterrestrial who had arrived from another planet. I was so isolated. But I ended up being able to exploit my alienness for my personal gain. [Laughs] I would amplify the exotic factor in people’s minds to make things more fun for both of us. I mean they were really naive — if I said I owned a hundred oil fields and rode to school on a camel, they would believe me totally. But what was it like for you, navigating into Russian society?

TAB: We didn’t really begin to integrate until after that first year, when we entered university and started getting to know Russian students. If we seemed exotic to them, it was mostly because of our stuff. Whenever we were outside, people were always staring at what we were wearing — our shoes, our jeans, especially. They would chase after us, trying to get us to sell them our jeans right then and there. Sometimes I would say, “Are you seriously thinking I’m gonna go home in my undies?” [Laughs] But of course, you know, by the end I had very deep ties to Russian friends. It was strange to discover how oriental they were — even more than us! Their traditions and rituals, their very close families. They were very conservative. They would never accept a woman having extra marital relationships, for example.

MAQ: Even though officially they were atheist communists?

TAB: They were still very religious people, in reality. They pretended they were liberated, but they were not.

MAQ: I mean, they were still selling religious icons everywhere, right?

TAB: Yes, though that was mostly for tourists. There was a group of Russian students with me at university who were professionals at making imitation icon paintings, which they would sell on the sly. I was inspired by them to make my own icons.

MAQ: Didn’t it seem ill-fitting for you to do that, especially since you were Muslim?

TAB: Not at all! For one thing, most of the artists I knew who made icons weren’t actually believers. And I was completely in love with church art, anyway. I’d studied Andrei Rublev, all the gothic masters. The art of the Russian Orthodox church was very different from the Roman Catholic church — it was very abstract. Andrei Rublev was an abstract painter to me. I really loved the lines they used, the sense of dynamic movement. I wasn’t that interested in the subject matter — I just liked visiting churches to look at the icon paintings. It stayed with me. For example, my solo show in 1996 was based on icons. The Kuwaiti newspapers accused me of being a Christian convert!

MAQ: There were all these things that you’d carried with you from your days in Russia, which they didn’t understand…

TAB: This world still lives inside me. All of my paintings of angels, my writings about angels… Even, when I was thirteen or fourteen, I was always dreaming about angels. I felt they were living inside me. The wings, they’ve always been there somehow. I like this world and I don’t want to get rid of it.

MAQ: But in our society, when you paint a figure it’s as if you’re giving a soul to that being. Even for your generation, from a religious perspective, it was seen to be wrong.

TAB: I remember one time when I was young, I took a coconut and I made eyes and hair and a mouth for it and I placed it on top of the television. My grandfather cautioned me that when Judgement Day comes, I’ll have to give a soul to this “sculpture” that I’d made. But that was only because it was three-dimensional. Paintings were fine. Because the Shiites in Iran and elsewhere loved to paint their imams and saints all the time, it was considered okay. The story of Hassan and Hussein had to be illustrated in so many different ways just to get through to people, you know? And then the poetry of Saadi and Hafez and Omar Khayyam. And all the miniatures.

MAQ: So you’re saying that it was only in the Gulf region that figurative art was considered bad.

TAB: No, actually — even here, into the 1970s, it was fine, too. A lot of local artists would paint figures. It was the norm. But then by the middle of the 1980s those figurative artists started disappearing. Soon they were painting fruits and flower pots.

MAQ: [Laughs]

TAB: And then after that, it became pure calligraphy. Now when you ask them why, they will say that painting figures is haram. A friend of mine continued painting figures, but only from the back — he would hide their faces, because that was the forbidden part.

MAQ: It’d be funny if it weren’t so sad. It reminds me of my project Muhawwil, about the faceless figures in Kuwaiti public art.

TAB: Basically when the real fundamentalist religious wave arrived, Kuwait lost a lot of really good artists. But I think they were foolish to stop.

MAQ: I guess the last big thing I wanted to ask you about is Iraq. I know you went a number of times, both personally and professionally. Do you remember the first time you went?

TAB: I was five years old. We went to Najaf, which is a whole town that is basically just a cemetery. The biggest cemetery in the Middle East. My aunt had just passed away and she was being buried there, so the whole family was paying a visit to her grave. It was my first time in a cemetery with dead people and graves, so I started imagining things about ghosts and monsters… and then suddenly I slipped and found that I was inside an open hole. It was an old abandoned grave! I had fallen on top of a skeleton — I was staring at him and he was staring back at me. The hole was so deep I couldn’t get out, so I was screaming and crying until my mother realized I’d wandered off and came back to find me.

MAQ: You must have been so scared!

TAB: It was horrible. But then the first time I went as an artist was in 1970. That was a great trip. I was a member of the new arts association in Kuwait and they had nominated me to participate in an exhibition in Baghdad. My father said I was too young to travel alone — I was only eighteen — so he came with me. I went to Mosul for the first time and saw all the ruins. The art scene in Iraq was really something back then. I went to all the galleries and shows.

MAQ: At that time, it was much more advanced than Kuwait.

TAB: Of course. The art scene in Iraq was extremely advanced and diverse.

MAQ: Much later you participated in the Baghdad biennial, right? What year was that?

TAB: It was called the Saddam Biennial of Humanist Art, that was the official name. I was in it twice, actually. The first time was in 1986. I had a painting in the show and I flew there to attend.

MAQ: Humanist art!?

TAB: Yes. There were intelligence agents everywhere. At one point I got sick and went to see the doctor at the hotel. When I entered the room there was a big hairy man sleeping on the patient’s bed next to the doctor. I objected — who is this man here with us? The doctor said not to worry. I insisted that we do our visit in private, so he examined me in the bathroom. Then the guy got up. He claimed to be the doctor’s driver. Obviously, he was just mukhabarat.

MAQ: This was in the mid-1980s, when Iraq was very much at war with Iran. How did it feel, being in Baghdad at that time?

TAB: I was very confused. It was so different from my earlier visits. It was a huge event — there were artists from every corner of the globe represented in the biennial — but so many of the works were just portraits of Saddam. Artists were glorifying him like a hero or a god; there were images where he looked like a prophet, with a halo around his head. I felt that what was going on was extremely unhealthy.

MAQ: So then you were supposed to be in 1990 biennial, right? Which was canceled after Iraq invaded Kuwait in August of that year… ?

TAB: Yes. I had already sent work to be included in that one, and I was planning on attending the exhibition when it opened in October. But by that time there was no biennial — there was a massacre. The funny thing is that when I went to Iraq during the war to visit relatives who’d been imprisoned there — buses were arranged for this kind of thing — I stopped by the Saddam Center for the Arts and got my paintings back.

MAQ: Was it strange for you… I just keep wondering what it must have been like, coming back to Kuwait in the middle of the Iran–Iraq War, with your family background. People in your extended family were perhaps much more on the side of Iran, even as the Gulf states, including Kuwait, were all sided with Iraq. Wasn’t it a dilemma?

TAB: At the time, we were very conscious that what was happening was the fault of the system, not the people. So those like me who had Iranian roots didn’t blame the Iraqi people. It was the fascist military system that was acting this way. It was a real human tragedy. At the time I wrote articles — albeit “masked,” in a way — saying that war was bad, that what was happening was dangerous, that children were dying. I wanted to convey the message that in war no one wins, that there are victims on all sides.

MAQ: Kuwait was very pro-Saddam at the time.

TAB: There were still the remnants of Pan-Arabism at play, sectarianism — you know, is it the Persian Gulf or the Arabian Gulf? A lot of people in the region were dreaming of Iran’s demise as their ultimate goal. They were arming Iraq. Then the fat cat had too much to eat and turned around and bit them…

MAQ: You lived the entirety of the first Gulf War in Kuwait, and you’ve engaged with that period very clearly in your art and your writing since. But I know there are things that happened to you that nobody’s actually heard before. I only found out about them much later, when we were growing up — I mean Fatima and I were really young at the time, so our experience of the war was completely different; we were oblivious to what was actually going on. Our lives felt like a video game at times. But didn’t you once have an experience that was more like a James Bond movie? Something about a bank vault and a heist, or…?

TAB: Yes, it was totally James Bond-esque. My brother was a business man and he had entrusted some of his prized possessions to a bank before the war, which included slabs of solid gold, his wife’s diamond wedding jewelry… just a lot of expensive stuff. So he had asked a woman who worked at the bank, someone that he trusted, to give me the keys to the vault. The plan was for me to open it, as his family member, and then give her what was inside so she could smuggle the goods out to Jordan and then on to him in London. This was extremely risky, because the bank was full of Iraqi soldiers. They had seized all of the assets inside — nobody could actually reach the vault. But this woman knew someone who was able to bribe an Iraqi officer to let us in — just to check to make sure that everything was still there, of course. [Laughs] This was such a dangerous situation for me to be in. If the soldiers discovered that I was trying to smuggle valuables out of the bank, they would have executed me on the spot! Me and everyone who was with me. But I did it. I went in there and got the gold and stuffed it into the bag and left the building. I was sweating so much I felt like a bag of chicken soup.

MAQ: How terrifying!

TAB: But I have another story that’s even scarier. In the first months after the invasion, there was an American journalist named Caryle Murphy who was working for the Washington Post. People were hiding her in one of the houses around the area. Basically, we collected photos and documents for her and she would send them back to the US, I don’t know how. So, the American press was getting coverage from inside Kuwait and the Iraqis were scratching their heads, because all media had been totally banned. My husband was a member of the resistance, and he was tasked with doing this collection of press coverage. He had a camera that he would use to shoot photos of soldiers, tanks, weapons depots — you name it, it was in that camera. So one day I’m driving and I get stopped at an Iraqi Army checkpoint — there were like twenty of them in every area — and the soldier asked me for my ID, so I opened the glove box to get it for him and my husband’s camera was just sitting there.

MAQ: Oh my God. You had no idea?

TAB: And you have to understand — there was a decree that if they found you with a camera, the punishment was death. Maybe if the film was empty they would let you off, but if there were images in it… So I’m just staring. I remember that at that moment, there was a French song playing on the cassette player.

The soldier asked me about the camera. My mind was racing. I told him I had been taking pictures of my daughter’s birthday party earlier that day and then accidentally left the camera in the car.

“Yes,” he said, “but you know this is forbidden. It can get you into a lot of trouble.”

Then he asked me what this music was that was playing. It was a love song, I said. I told him I’d been dreaming of going to Paris. And then I told him, sweetly, “One day, I’ll take you there with me.”

MAQ: What?! Really?

TAB: Yes. I transformed into a sexy Egyptian actress. It was the only way I could think of to survive that moment. He said that his dream was to go to London. I said, “I speak English, I speak French — whatever you want. I can show you places all around the world.” He said, “What about your husband, your children…” I said, “I’ll leave them for you.”

MAQ: Oh my God.

TAB: I said that! I told him that he was young and handsome and that I’d follow him to the ends of the Earth. When this war was all over, I’d take him on a European tour. We’d stay at the fanciest hotels, eat the best food. He could see all of his favorite cities. Gradually, I could see his eyes sparkling — he was getting into the mood.

Finally, he said, “Okay, keep the camera. Hide it so nobody executes you. If I show it to the other police officers, you’ll be hanged on the spot — and then they’ll burn your house down for good measure. But you are a beautiful soul, and you gave me a dream. It’s a promise, right?”

“Yes, I promise,” I said. “When this war is over, I’ll come find you and take you to Paris.”

And then, as if by magic, he let me go. When I got home I cried my eyes out and screamed at your father for putting me in that position. They were gonna execute me if I didn’t know how to sweet talk!