Miami

The Art of Aggression

The Moore Space

April 14–July 1, 2005

Countless historical examples exist of artists responding to acts of aggression. From Edouard Manet’s late nineteenth century drawings and paintings of the Franco-Prussian War to Picasso’s powerful, huge Guernica to Warhol’s pop reproductions of race riots, artists have been drawn to violence in everyday culture as well as to the political environment and public policies that instigate and encourage such aggression.

A recent exhibition in Miami at the Moore Space showed work that references such art historical precedents. The curators of the show appear to be evoking the German philosopher Herbert Marcuse’s concept of formalism’s connection to beauty as political critique; Marcuse offered that because art is an idealization, it is often at odds with the subject matter it represents and therefore has the ability to break down “established reality,” finally making the fictive world of art form a new reality. Upon viewing The Art of Aggression, however, with few exceptions, one questions the ability of most of the work presented to hold such ambitious transformative powers, or to create the room for nuanced realities, for that matter.

Mark Lombardi exhibits exhaustive drawings of flow charts connecting the corrupt and questionable dots between terrorists, arms dealers, the US government and even the Bush family’s private companies. While Lombardi’s conceptual narratives read like a Vanity Fair investigative report on the infuriating injustices of who is getting rich off the spoils of war, the strongest illustration to such a story is told in the massive human cost of war. The curators claim “that form or beauty is an important tool in political art” and that Lombardi’s work has the ability to “overturn our expectations about reality and illusion.” A pressing question comes to mind here regarding this work specifically and the exhibition in general: Is it really likely that anyone who voluntarily goes to an alternative art space to see a show called The Art of Aggression is going to have their perceptions changed as to the role the US plays as an aggressor in the world? And is that the point at all?

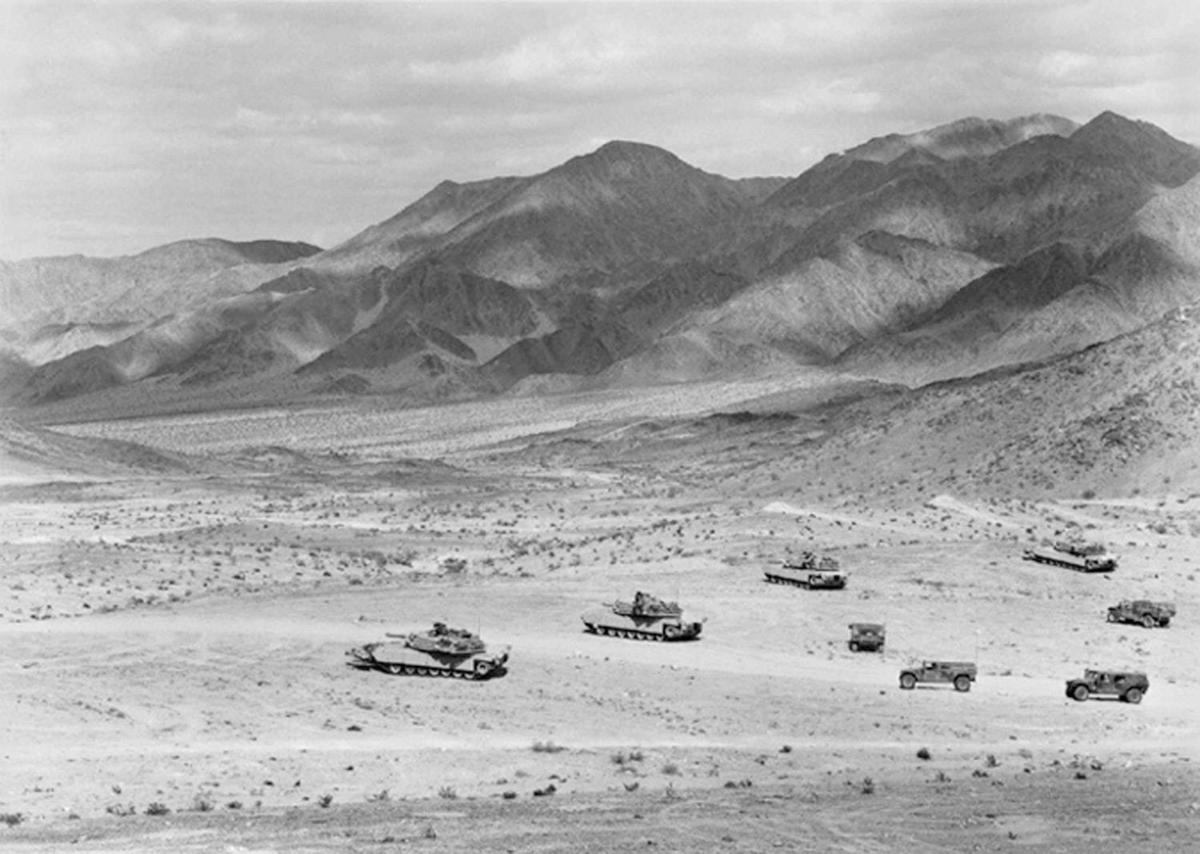

The primary focus of the exhibition is an entire room dedicated to sketches and watercolors from the Iraq war by New York–based artist Steve Mumford. Given press credentials by the online art magazine Artnet.com, Mumford made four trips to Iraq in 2003 and 2004 to chronicle military and civilian life in the US occupied region. Baghdad Journal, an account of his time spent in Iraq, first made an appearance on Artnet.com via images depicting American soldiers on the frontline and Iraqi citizens trying to maintain some semblance of normality in the middle of a war zone. The resulting work oddly recreates the feeling one has when looking at courtroom sketches. The weight of the reality for both soldiers and Iraqis is removed by virtue of the renderings, given that our already (over) trained eyes are exposed to more real, graphic images in the daily mass media. Inspired by Winslow Homer’s Civil War paintings, the fact that the artist went into a war zone with such anachronistic tools as pencil, watercolors and paper is nevertheless of particular interest in an age of digital reproduction.

The only other painting in the exhibition is a single canvas by New York–based Wayne Gonzales, depicting a stylized representation of the Pentagon. With its army green background and silver Lichtenstein-style dots (in this case photographic pixels) organized in a geometric abstract manner to form the likeness of the icon of American military power, the painting seems more an object of pure beauty than a demonstration of outright aggression. It is of interest here that Gonzales takes photographs found in newspapers and the mass media renders the images in paint, while the rest of the artists in the exhibition choose to employ the more immediate mediums of film and video. While the images are at times powerful, as in the case of Mary Ellen Mark’s intimate black and white photograph of an amputee laying down with his fiancée, missing leg exposed, or even compositionally stunning as in the case of Martha Rosler’s photographic collages juxtaposing the American comforts of a luxurious kitchen with an image of torture from Abu Ghraib, the aggression in these images seems to fall short of the effect of the daily images we receive via the media. Nevertheless, Rosler does manage to create a jarring, if not slightly hackneyed, juxtaposition.

The work in this show that comes closest to grandiose transformative ambitions is one that is not so overtly political, but rather, shows a simply human side of conflict. Palestinian-born artist Emily Jacir’s video Crossing Surd features the artist carrying a video camera at foot level in her bag as she crosses a border zone. The weather is cold and damp, the people looking as depressing as the gray sky. We can hear her boots struggling through the mud that is supposed to be a road. This is the realism of form and beauty that the early modernists such as Manet strove to representing in their work — as a means of transforming the current reality. The video is simple, the landscape is neither staged nor dressed, the people, unscripted and not cast for the part, rendering it absolutely “real.”

In the end, the issues of American involvement and policies in this region are not a matter of black and white — as they tend to be outlined in drawings or documented in photographs in this exhibition — but rather entail many shades of gray. While an important initiative, a more successful exhibition of works could have left a bit more room for nuance, less reductionism and, finally, a privileging of the aforementioned shades of gray.