Born in Cairo in 1913, Albert Cossery wrote eight novels in sixty years, all of which celebrate his philosophy of laziness and boast a cast of hedonists, vagrants, anarchists, and thieves. Written in 1999, Les couleurs de l'infamie was Cossery’s last novel before his death at the age of 94 in 2008.

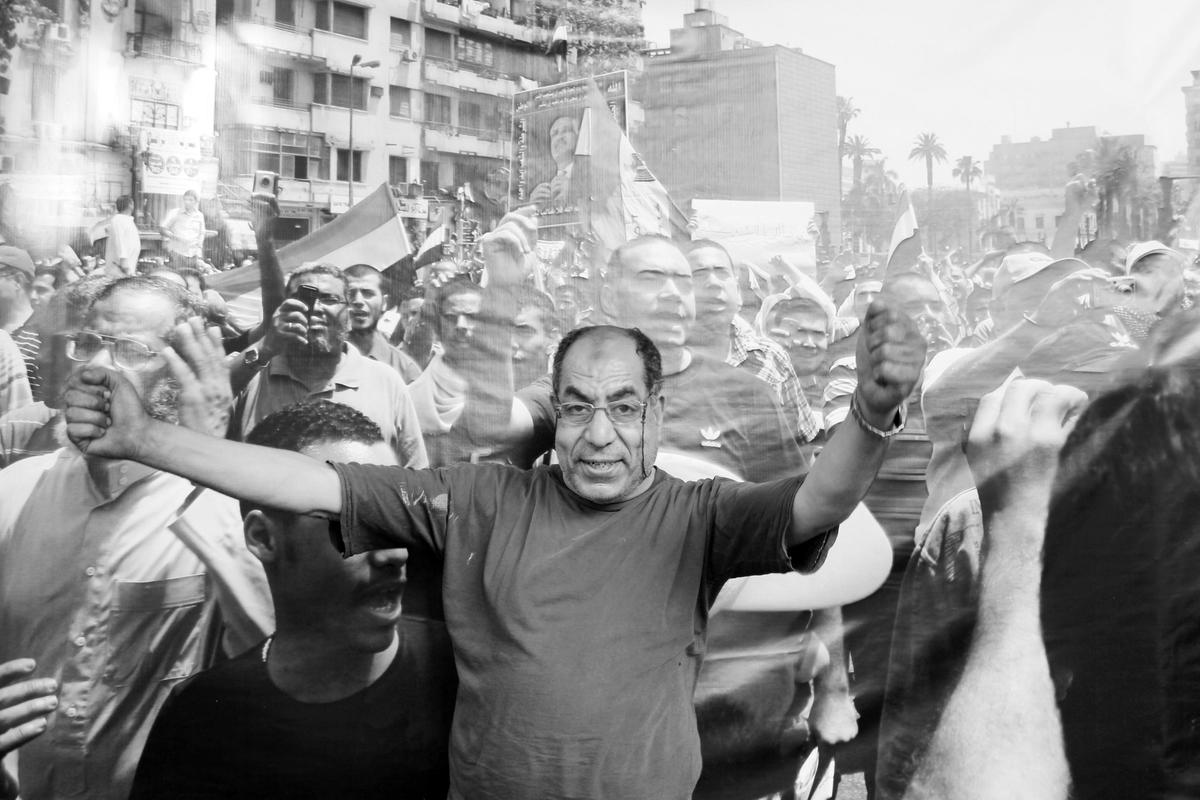

The human multitude meandering along the torn-up sidewalks of the ancient city of Al Qahira at the nonchalant pace of summer seemed to be dealing serenely, even somewhat cynically, with the steady, irreversible decay of its surroundings. It was as if all these people, stoically strolling beneath the incandescent avalanche of a molten sun, were, in their tireless wanderings, benignly colluding with some invisible enemy eating away at the foundations and buildings of the erstwhile resplendent capital. Immune to drama and devastation, this crowd swept along a remarkable variety of characters pacified by their idleness: workmen without jobs; craftsmen without customers; intellectuals disillusioned with fame; civil servants forced from their offices for want of chairs; university graduates sagging beneath the weight of their futile knowledge; and finally those inveterate scoffers, philosophers in love with their tranquility and shade, who believed that the spectacular deterioration of their city had been expressly created to hone their critical faculties. Hordes of migrants had come from every province with preposterous illusions about the prosperity of a capital that had become a hive of activity and they had latched on to the local population, forming an appallingly picturesque pack of urban nomads. In this riotous atmosphere, cars sped by like driverless machines heedless of traffic lights, transforming any vague notion a pedestrian might harbor of crossing the street into an act of suicide. Along the thoroughfares neglected by city maintenance, apartment buildings doomed to imminent collapse (whose landlords had long banished from their minds any pride of ownership) displayed, on balconies and terraces converted into make-shift lodgings, the multihued rags of their destitution hung out like flags of victory. The dilapidation of these dwellings brought to mind an image of future tombs and gave the impression, in this country awash with tourist attractions, that all these pending ruins had over time come to be prized as antiques and were therefore not to be touched. In some places water from a burst sewer pipe caused a pool as wide as a river to form, where flies pullulated and from which wafted the effluvia of unspeakable stenches. Naked and unashamed, children entertained themselves by splashing about in this putrid water, sole antidote to the heat. The streetcars overflowed with clusters of people as if it were a day of revolution, and dug out at a snail’s pace a pathway through the rails obstructed by the pressing mass of a populace that had long ago gained expertise in strategies for survival. Resolutely circumventing every obstacle, every pitfall in its path, this populace, discouraged by nothing and with no particular goal in mind, continued its journey through the twists and turns of a city plagued by decrepitude, amid screeching horns, dust, pot-holes and waste, without showing the least sign of hostility or protest; the awareness of simply being alive seemed to obliterate any other thought. Every now and then the voices of the muezzins at the mosque entrances could be heard emanating from loudspeakers, like a murmuring from the beyond.

More than anything, Ossama enjoyed contemplating the chaos. As he leaned his elbows on the ramp of the elevated tracks that encircled Tahrir Square with their metallic pillars, he was contemplating ideas that flew in the face of the theories propounded by those certified experts who swore that a country’s continued existence was predicated on order. This absurd notion was utterly belied by the spectacle that spread before his eyes. For some time now, he had been using this structure, dreamed up by humanist engineers to shield the miserable pedestrians from the street’s dangers, as a panoramic observation deck to reinforce his profound conviction that the world could go on living indefinitely in disorder and anarchy. And indeed, despite the elaborate free-for-all that dominated the huge square, nothing seemed to alter the population’s mood or its spirited gift for sarcasm. Ossama was convinced that there was nothing more chaotic than war; yet wars lasted for years on end and it even happened that notoriously ignorant generals won battles because shock, by its very nature, is a great producer of miracles. He was thrilled to live among a race of men whose exuberance and loquaciousness could not be spoiled by any iniquitous fate. Rather than fulminating against the problems they faced because of their city’s outrageous decrepitude, they behaved affably and civilly, as if they attached no importance whatsoever to those material inconveniences that could lead to suffering in petty souls. This dignified, noble attitude filled Ossama with wonder, for to him it was a sign of his compatriots’ complete inability to fathom tragedy.

Ossama was a young man, about twenty-three years old who, although not strikingly handsome, nonetheless had the face of a charmer; his dark eyes shone with a glimmer of perpetual amusement, as if everything he saw and heard around him were inevitably comic. He wore with incomparable ease a beige linen suit, a raw silk shirt set off by a bright red tie, and brown suede shoes. This outfit, quite ill-suited to the scorching heat, was not the result of some personal wealth, nor was it due to a taste for show; it was donned solely to reduce the risks inherent to his profession. Ossama was a thief; not a legitimated thief, such as a minister, banker, wheeler-dealer, speculator, or real-estate developer; he was a modest thief with an income that varied, but one whose activities — no doubt because their return was limited — have, always and everywhere, been considered an affront to the moral rules by which the affluent live. Possessed of a practical intelligence that owed nothing to university professors, he had quickly come to learn that by dressing with the same elegance as the licensed robbers of the people, he could elude the mistrustful gaze of a police force for whom every individual who looked as though he lived in poverty was automatically suspect. Everyone knows that the poor will stop at nothing. Since the beginning of time, this has been the only philosophical principle by which the moneyed classes swear. For Ossama, this dubious principle was based on a fallacy because, if the poor really stopped at nothing, they would already be rich like their slanderers. Consequently, if the poor continued to be poor, it was simply because they did not know how to steal. In the days when Ossama had lived his life as an honest citizen accepting poverty as his inevitable lot, he’d had to put up with the wariness his rags aroused in shopkeepers and closed-minded members of the police force. At that time, he had felt so vulnerable that he dared not go near certain city districts where the privileged set led their glittering lives for fear he would be suspected of evil intentions. It was only later—once he’d at last caught on to the truth about this world—that he’d decided to become a thief and, in order to carry out his trade with respectability, had adopted the visible attributes of his superiors in the profession. From then on, suitably attired, he could without difficulty frequent the lavish milieus where his masters in plunder lounged about, and steal from them in turn with elegance and impunity. True, with these petty thefts he recouped a mere fraction of the fantastic sums that these unscrupulous criminals amassed without a thought for the misery of the people. Yet it must be pointed out that Ossama’s objective was not to have a bank account (the most dishonorable thing of all), but merely to survive in a society ruled by crooks, without waiting for the revolution, which was hypothetical and continually being put off until tomorrow. Cheerful by nature, he was predisposed to humor and mischief rather than to the demands of some dark and distant revenge.

He thought he’d had enough of admiring his compatriots’ performance as they attempted to dig themselves out of the chaos and he was about to leave his observation deck when — ever on the lookout for an entertaining detail — his eyes were drawn to a scene transpiring on a traffic island that served as a streetcar station. Several plump, buxom women carrying innumerable packages and straw baskets were conferring with a burly young man who wore a tattered t-shirt and some sort of filthy fabric draped about his hips as if he were a classical statue representing destitution. These monumental nymphs had apparently just climbed off a streetcar and seemed to be having some bizarre dealings with the scantily-clad fellow — unfortunately the distance and the ambient cacophony made them inaudible. Ossama was concentrating, trying to make out the nature of the discussion when suddenly it came to an end in an unexpected way. He saw the man take the females, who were terrified by the permanent onslaught of cars, under his protection, raise his arm skyward as if to invoke the name of Allah, and escort them onto the roadway in a blaze of horns, until they reached the haven of a sidewalk. Having arrived safe and sound, the survivors unknotted their handkerchiefs and each gave a coin to her savior who, having caught his breath, was already offering his services to any number of pedestrians hesitating at the edge of the sidewalk, still stunned by his exploit. Ossama keenly felt all the hilarity of this one-of-a-kind scene. Street crosser! This was a new trade, even more daring than that of thief because one risked a violent death; it was a trade he could never have dreamed up even in his wildest theories about the ingenuity of his people.

Excerpt from Albert Cossery’s The Colors of Infamy, translated from the French by Alyson Waters, forthcoming from New Directions in November 2011