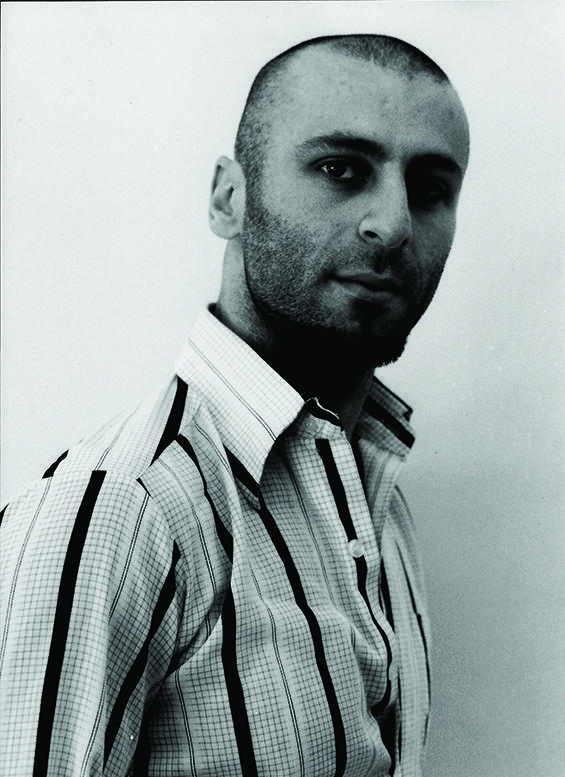

Rami Kashou is loaded. Not like that — not in terms of affluence or inebriation — but to be a Palestinian Angeleno involved in cultural revolution today means you are about as loaded as an Operation Iraqi Freedom rifle. The relentlessly humble, soft-spoken 27-year-old would deny fashion was his chosen instrument for revolution, but it’s there. After all, Kashou’s forthright flair for an everyday ready-to-wear iconoclasm has been getting its fair share of buzz in the New York and European market, but it’s more LA and the Middle East that he has to worry about mastering — and interestingly worry is the last thing on his mind.

As the fashion-prodigy story goes, the Jerusalem-born Kashou spent his early adolescence sketching designs for his mother to take to a seamstress, then moved to the States for fashion school at 18, dropped out, bought some sewing machines, and got the ball rolling from there. He was able to sell a few of his pieces among the mostly-Miss Sixty hangers of Super, the now-defunct Melrose megaboutique where he was an early employee. Kashou’s aesthetic then developed with an innovative T-shirt line, which manifested early symptoms of his soon-to-be-trademark delicate deconstruction streak. Soon his one-of-a-kinds were snapped up by Los Feliz fashionista-fixture Aero & Co., and was featured for their 2001 trunk show. Being showcased by Gen Art in 2001 gave him the confidence to self-finance his first show in his dream location: the historic Los Altos building (“where Bette Davis used to live,” he gushes — not to mention Greta Garbo and Judy Garland). Acoustic it-girl Nikka Costa showed up, pre-Versace Christina Aguilera planted herself on a front row seat, and trend-lusting celebutante Tori Spelling took her already-warm spot as a Kashou regular. Kashou’s initiation was finally cemented with a runway shot on the cover of Women’s Wear Daily in April 2002.

Kashou is not one to namedrop, but once you fish it out of him he reveals that Pink was one of his first clients. Erykah Badu, who’s bought over 18 pieces, sported a Kashou kaftan through much of her last tour. Portia de Rossi and Amy Smart are devotees. Winona Ryder has — legally — nabbed a few pieces. He even designed a high-end-jersey wedding dress for Dixie Chick Martie Maguire. Kashou leaves it up to them to come to him — as someone who hasn’t owned a TV in years and who considers the opera as a satisfying nightlife pastime, he clearly isn’t one to lust after the celebrity circuit.

But one can’t help note the star-power equation in the way Kashou can merge strength and sexiness. What could be more ideal for spot-lit alpha girls than pairing almost baroque Grecian drapery with a subdued material minimalism? Kashou’s slit-sleeved blouses are sharp not cute, his wrap-jackets are striking not silly, his gathered blouses and pleated skirts are regal not just flirty, and his signature jersey dresses insist on total form and functionality. “My work expresses confidence — an edge without being obnoxious. It’s between vintage and progressive,” he says. His recent Fall 2004 collection adds even bolder pieces to the wardrobes of handsome urban femmes, rather than just easy-breezy Kashou-belles. You can expect a palette that’s darker, stronger, just barely accented with whimsical touches like gold threading and muted metallics. “It’s more masculine, less drape-y, with simpler lines,” says the designer. “More construction as opposed to the early era.”

What gels well with Kashou’s non-derivative reinventions is his distinct maverick streak — Kashou is obsessed with existing outside of convenient identity politics. He’ll go as far as featuring a cutout peace sign on the back of a dress, but he isn’t seeking recruitment to save the world. Whereas one might imagine a Palestinian designer could get a lot of bang out of playing the politics buck, Kashou won’t rush to claim his Middle Eastern heritage as a vehicle behind his inspiration. “I think there is a Middle Eastern element — how I drape my fabrics maybe — but it’s also European,” he explains. “I don’t cater to a specific ethnicity. I don’t let that limit me. I don’t think as a Palestinian as I design.” However he knows his fame can contribute to changing any ignorant misperception of Middle Easterners: “That’s how I want to give back somehow.” Kashou isn’t sure how his work would be received in the Middle East, but, as he notes, “in [some countries], women who wear veils, underneath they’re sometimes wearing the shortest, tightest Gucci miniskirts!”

Kashou is also somewhat ill-at-ease in his transplanted LA, where the answer is not to claim the culture either but to develop it. Like many hipper Angelenos he’s gravitated towards the East Side, like his own Echo Park neighborhood: “It’s very real. And I’m inspired by anything away from Hollywood and Beverly Hills!” he says. But he still has to deal with L.A.’s frustrating aspects, most notably how Angelenos appear stunted when it comes to sartorial savvy-ness. “‘Sexy’ is a little too pornographic in some people’s thinking in LA. People tend to be more followers and so body conscious. I’m trying to open people’s minds in identifying sex appeal in a different way.” How to teach the left coast Juicy-Couture-fiending and eternally-J-Lo-ing masses? “I might expose a woman’s back instead of breasts,” he says. “You know, being sexy… without being obnoxious!”

While Kashou still isn’t affiliated with a showroom, and has pieces only in Aero and Co., one gets the feeling things will soon take off for him. But for now, he’s happy to be living in the same studio he works in — where he toils alone and does all of his own patterning, cutting, measuring and fabric dying — for exclusive special-clientele commissions. After all, he’s mastering the trickiest part of any creative profession: wholly living one’s art. He does it so well that when he rattles off a favorite visionary cliché, “It’s more of a lifestyle than a job,” you actually believe him.