These objects are fully independent of humans. Autonomous in sentience and intention, they are generally depicted as relics, forged from inorganic materials (stone, metal, bone, ash, soul, etcetera). Autonomous or sentient objects — or demons, as they were known to the ancient Assyrians — exist in a subaltern state, buried within the bowels of the earth or inside another object, slumbering, their shapes almost always assuming provokingly exquisite forms, as if nourished by radically different laws of space and time. From the human perspective, these objects are distressingly offbeat and off-time.

As genres obsessed with the inner logics of objects, pulp horror and science fiction reveal that inorganic outsiders cannot be destroyed save by exerting the power of another object on them. But employing demonic logic to slay a demon inevitably evokes another demon. In this, horror’s insight represents a return to the Assyrian medical tradition of demonism, in which “doctors” attempt to expel one demon from the patient by summoning another demon to possess the sick person in its stead — a tradition according to which every human is always a puppet of an outsider, suspended in a labyrinthine network of demonic possession.

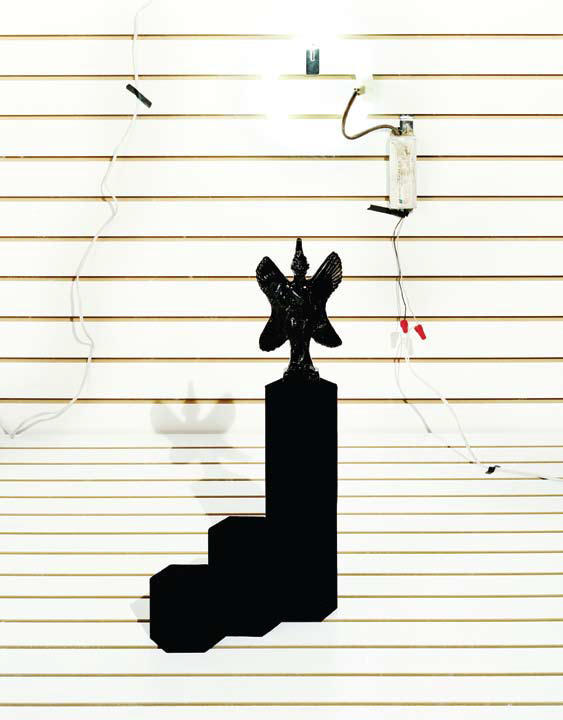

Sentient objects and xenolithic artifacts manifest their antagonism by encroaching on human actions that involve sense, consciousness, or experience. Artifacts unfold their true demonic thinghood only on achieving proximity to a human host. It is at this moment that the object as a demon begins to peel the skin off the human and dresses him as its own puppet. Pulp-horror stories suggest that with each step in the process of sensing or possessing the object, the object adds another string to the human puppet, becoming a puppeteer with no sense or purpose. Examples of sentient relics and artifacts that threaten the self-possession of humans are numerous; examples might include the amulet of the Pazuzu demon in The Exorcist, the One Ring in the Lord of the Rings, the Lament Configuration in the Hellraiser film series, the oil lamp in Aladdin and the Enchanted Lamp, and the Soul Cube in the video game Doom 3.

As what can be called a contribution to lumpen Orientalism — the term is borrowed from China Miéville — horror and science fiction present sentient objects with names that resonate with the nomenclatures of Near and Middle Eastern languages. The names associated with these objects cannot be directly imported into the vocalization systems of the Indo-European languages, as with Ghatar, the country, which is sounded in English as “guitar” or “gutter.”

The Middle East in its geographical obscurity and geopolitical remove serves as a generous host for inorganic demons and alien relics — a pulp lair for all objects that can be considered insurgent by virtue of their complete autonomy to human will, desires, and abuses. These relics have names only in order to give humans an objectified relief. Rather than a means of comprehending these objects, their names convey the elusive horror of the Thing. But demons are not identified by names; they are individuated in their collectivity — a horde or legion or army, a river or an ocean. Beelzebub (ba’al zebub), the festivity of flies. Pazuzu, a sky-blackening swarm of locusts, enforces the reign of “dust” — itself the most prevalent Middle Eastern relic. So what, then, is the name of that other terrestrial relic, oil, with which the Middle East is drenched? An avatar of a sun god, descended to the bowels of the earth to enlighten earthly beings in their own abode?

The sentient junk and alien oddities of horror stories are housed, hoarded, and occasionally disbursed by greedy Middle Eastern mongers. Indifferent to the trading ethics of civilized countries, inorganic demons and Middle Eastern markets converge on one another. The Middle East continues to resist the onslaught of politics, philosophical doctrines, and economic systems that advocate transparency and accessibility. The link between the Middle East and the demonic lies in their mutual resistance to the myth of anthropocentrism. The myth of anthropocentrism is the myth of intelligibility, the idea that everything can be made sensible, experienced, comprehended. It is the fantasy of total access. In the Middle East, its advocate is the capitalist profiteer, for whom “access to things themselves” is the new shibboleth of economic morality. According to both the anthropocentric agenda and the capitalist juggernaut, everything should be accessible simply because access is a function of affordability.

By closing their inner logic on themselves, the Middle East and its demons expose the redundancy of human intelligence and the myth of capitalism’s omnipotence. This is why they both appear as terrorizing superweapons, contagious and proliferating, for they reveal the fragility inherent to the logic of anthropocentrism and capitalism. This is the view from horror: a criminal alliance between the Middle East itself and the demonopoly of autonomous objects; a new dark age yet to unfold.