Cairo

Open Studio Project

The Townhouse Gallery

May 1-15, 2006

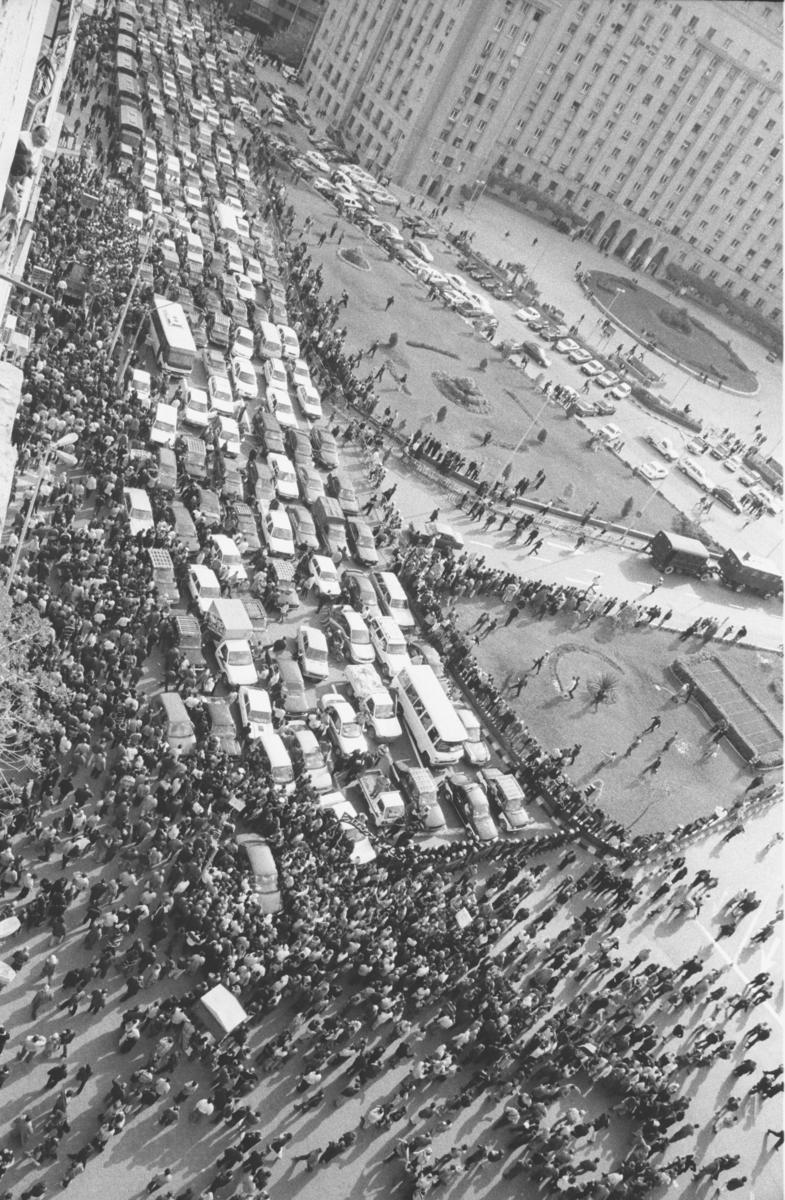

Bustling downtown Cairo is significantly busier than some of the more touristic or upscale neighborhoods of this city, such as Zamalek (where the Cairo Bienniale usually takes place) or Giza (where the embassies and big hotels are). Townhouse, embedded in a neighborhood filled with car repair shops, street eateries, and sidewalk cafes, is a quintessentially downtown venue that is open to the street below and inclusive of its activity. Somehow, the Townhouse staff is intensely focused amidst the noise, music, arguments, laughter, bad smells, good smells, political demonstrations, and lazy breezes wafting in and out of the always wide-open windows.

So when I arrived at Townhouse as one of the curators in residence for the Open Studio Project, it was immediately clear that this was an ideal place to host a sound program. Though this wasn’t the first Open Studio at Townhouse, it was the first one delineated by a specific medium — that of sound. Curator Clare Davies seized upon this as a way to experiment with a new model, as well as a way to bring Cairo’s homegrown sound practitioners into contact with a network of practitioners from other parts of the world. The aim, it seemed, was to build a worldwide network out of common interest and proximity, as well as through a well-designed website tracking sound activities. Perhaps because of co-sponsor Triangle Art Trust’s own interest in diversifying cultural representation, the invited practitioners hailed from various parts of the world. This year’s residents included: Rajivan Ayyappan (India), Anabala (Turkey), Regine Basha (US), Carlo Crovato (UK), Charbel Haber (Lebanon), Adham Hafez (Egypt), Geert-Jan Hobijn (Holland/Germany), Hassan Khan (Egypt), Myizer Matlhaku (Botswana), Greg Niemeyer (US), Maryam Rahman (Pakistan), Mahmoud Refat (Egypt), Mohammed Al Riffai (Egypt), Basak Senova (Turkey), Staalplaat Soundsystem (Holland/Germany), Paulo Vivacqua (Brazil) and Cynthia Zaven (Lebanon).

To our relief, “sound art” was not presented as a fixed term and the program retained the healthy character of an unlikely interest group still massaging its own parameters,its audience and its specific context somewhere between music and art. We also seemed to have been purposefully selected to represent wildly different production and circulation backgrounds: installation artists, video artists, sound engineers with commercial experience, experimental musicians from the club circuit, lo-fi noise performers, a choreographer/dancer, a spoken word performer/percussionist,a video artist,a new media gaming designer, a pianist and composer, fusion musicians and two curators with vastly different approaches. Though we all had engagement with sound on some level, our concerns sometimes varied dramatically. At first many of us seemed a bit stunned by the widely cast net we were caught in and the United Nations–like representation. But soon this revealed itself to be the most refreshing part of the program (too many pure sound artists in one room is not a good thing anyway), the arrangement managing to debunk our various preconceptions about what sound art is supposed to be, and allowing us to relax into more unlikely and individual correspondences with one another.

Also helpful was the insistent backdrop of Cairo’s densely aural downtown environment — the ultimate binding equalizer. For many of us, just learning how to cross the street together was the beginning of a bonding experience. Then came taking cabs, deciphering car honks, buying supplies, knowing when to rest, when to drink water, where to eat koshary, when to smoke, when to work, where to play. I would say it took an average of about four days to finally plough through the thick air of noise and dust and begin to articulate oneself in it. Once through, it all became rhythm, movement and beat.

This year saw Open Studio events, talks, screenings, and workshops sprawled throughout other sites in the downtown area, extending the context for production but making it difficult to negotiate physically and time-wise. The surroundings also seemed to cause some confusion for the few but dedicated visitors who were trying to keep up with it all,especially when major sandstorms and demonstrations interrupted the week. Most exciting were the more spontaneous jam sessions and dialogues that began to build between Cairenes and visiting artists — such as an extraordinarily layered performance by Charbel Haber, Mahmoud Refat and Hassan Khan at the Townhouse factory space, where Refat and Khan’s turbulent soundscapes were punctuated by Harbel tooling away with parts of his electric guitar. Also great was witnessing Botswanan drummer Myizwer Matlhaku lead a free-form percussion session with a number of local dumbek players, and excited discussions between Paulo Vivacqua and Mohammed Al Riffai about sound as material form. For the final weekend,Townhouse secured an abandoned building, the Hotel Viennoise, for a temporary exhibition of installations and performances, giving the artists a chance to occupy some ambitious spaces. Some pieces worked really well in this territory, while others felt more forced and awkward. Given the two-week schedule and diversity of our approaches, we might have benefited more from focusing on intramural sessions on the nature of production, process, dissemination and presentation of sonic works, rather than from the pressure of producing a final guerilla-style exhibition for the public — placing sound works back into the demands of a visually dominant format. Perhaps the “show” could have been realized as a follow-up to the residency, rather than running contiguous with it. But sound works found fertile ground in Cairo, and my hope is that it continues to thrive.