Cairo

The Pick 4

Townhouse Gallery

June 28–July 22, 2009

Two pieces stood out among the twenty works on view at ‘The Pick 4’ this past summer: 3m Hassan (Uncle Hassan) by Aya Tarek and A Letter to a Lover by Shereen Lotfy. Both artists belong to the “young and upcoming” demographic that has been the traditional target of ‘Pick’ exhibitions in the past. Were it not, however, for the seductive extroversion of each, these two works would have seemed to have little in common.

Although it was difficult to glean a common theme or distinct curatorial approach at work in the exhibition as a whole, the diversity and range of media (e.g., video, painting, sculpture, photography, and especially two pieces in sound) may be read as constituting, by default, something of a curatorial statement. Although no longer uncommon or exclusive to the so-called independent scene, the appearance of “new media” is still awarded a rather anachronistic distinction. As a result, when nontraditional media are included in a show, viewers can sometimes feel as though they’re cringing through an enthusiastic parental discussion of “youth culture.”

Ultimately, the prevalence of new-media works in 'The Pick’ — curated by Medrar for Contemporary Art, a group organized by and for emerging artists and designers in Egypt — figured as a kind of shorthand for “emerging artist,” without necessarily delivering on the associated virtues of innovation and talent. (Another hieroglyph for youth art is the widespread and disappointingly lazy reliance on design aesthetics by artists and curators alike.)

Medrar was not to blame for all of this. It is just that little else stood out that would qualify the strands of an argument or thread, not to mention anything so grand as a “moment.” The tricky enterprise of putting together a non-reductive yet coherent group exhibition is hard enough; that it’s expected also to represent faithfully the best of a cultural moment makes it no easier. The result, not surprisingly, is that exhibitions end up being about the strength of individual works rather than abstractions on the practices of young artists or their relationship to a scene. This is not a phenomenon particular to the Cairene scene or the Middle East more generally; anyone who walked through Younger Than Jesus or any one of the iterations of Greater New York probably remembers the merits of a handful of works distinguished by their deviance from, rather than any confirmation of, ostensible generation markers.

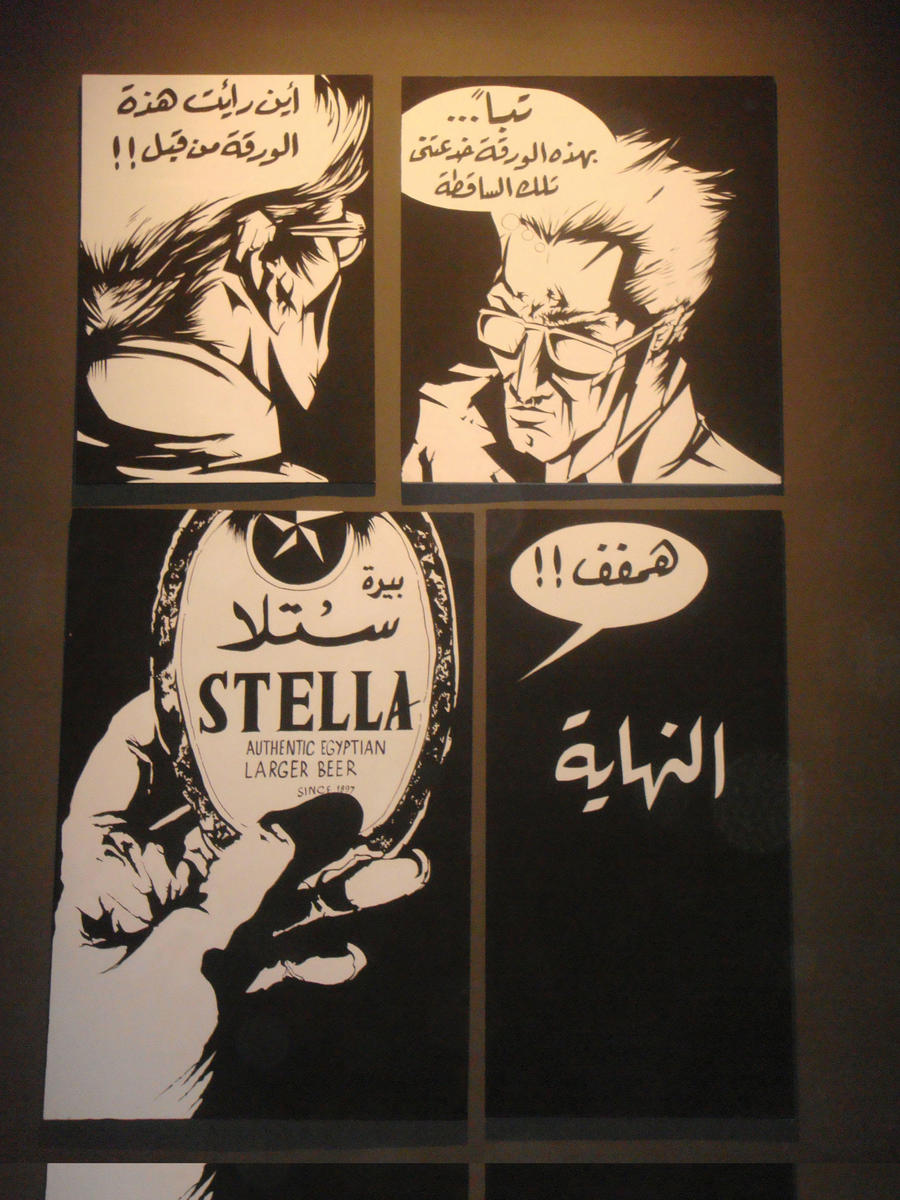

3m Hassan, a black and white painted work in the style of a graphic novel, took up significant wall space. Four rectangular comic strip panels depicting a young man speaking, a beer label from a Stella bottle, and the words “Al-Nehaya” (“The End”) made little sense on their own. The paintings’ clean lines and sharp contrasts complemented their confident disregard for contextualization. The wall text, too, was unapologetic; the artist added only an enigmatic, if evocative, clue: “In 3m Hassan I am exploring how the experience of living in somebody else’s art studio, using his materials, and living his lifestyle could really change that person’s way of thinking and his production of art.” One might imagine that the work was an outtake from a longer narrative, a monumental painting project spanning hundreds of meters of wall space. It was instead a one-off translation of the final page from a graphic novel, an ongoing project of Tarek, to the gallery space.

Tarek works in a studio on Alexandria’s Sharia Mahatet El Raml, named after the famous waterfront square in the center of the city. The studio belonged originally to her grandfather, a professional painter of film posters. Although only recently extinct, the painted-poster genre has already been snapped up by cultural nostalgists, as well as contemporary professionals. Artists as diverse as Lara Baladi, Hani Rashed, and Shirana Shahbazi have each reused or adapted some element of the long-standing handmade pop culture practice in their own work. Her grandfather’s métier is not, however, Tarek’s first interest. (She comes by her own idiom via Frank Miller animations and second-hand Marvel comics.) It is rather the occupation of a studio (his studio) that links their practices.

What was the difference between the comic book page original and its “fine art” equivalent as it appeared on the wall of the Townhouse Factory space? Besides the switch in medium, from ink to painting, and scale, from page to wall-size, little had changed. Nonetheless, though perhaps unintentionally, Tarek’s work had come full circle to intersect with that of her studio’s original protagonist: the poster painter. The combined text and image were emphatic and open-ended.

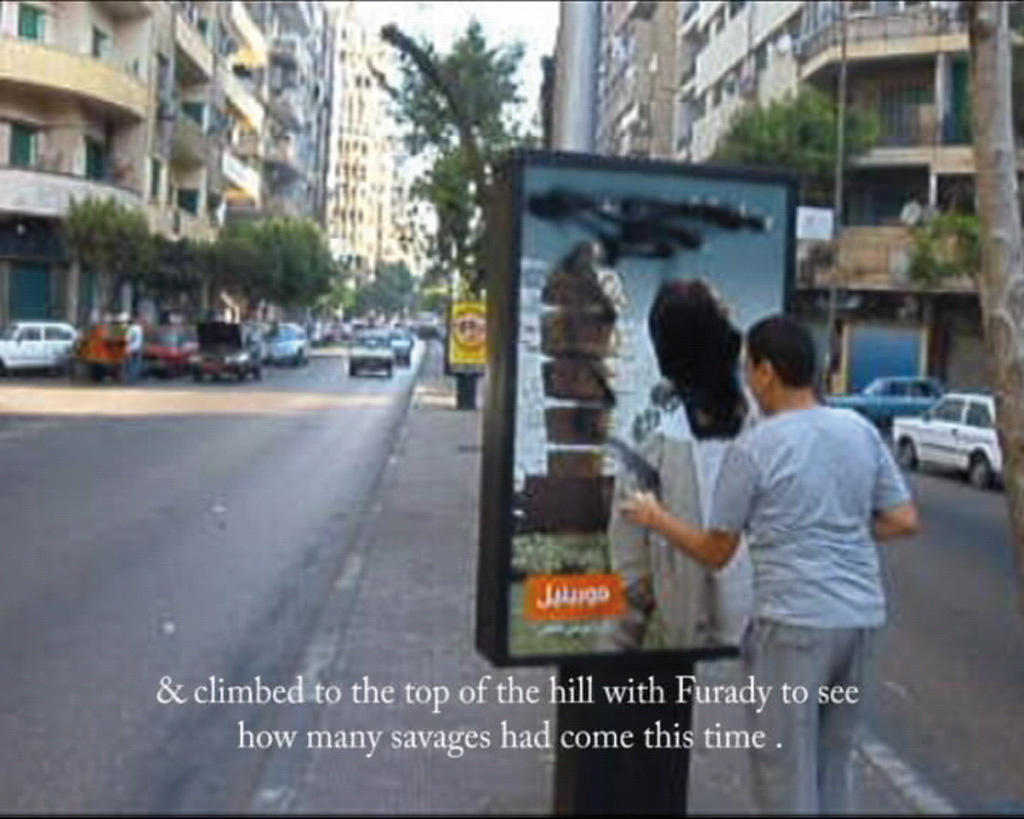

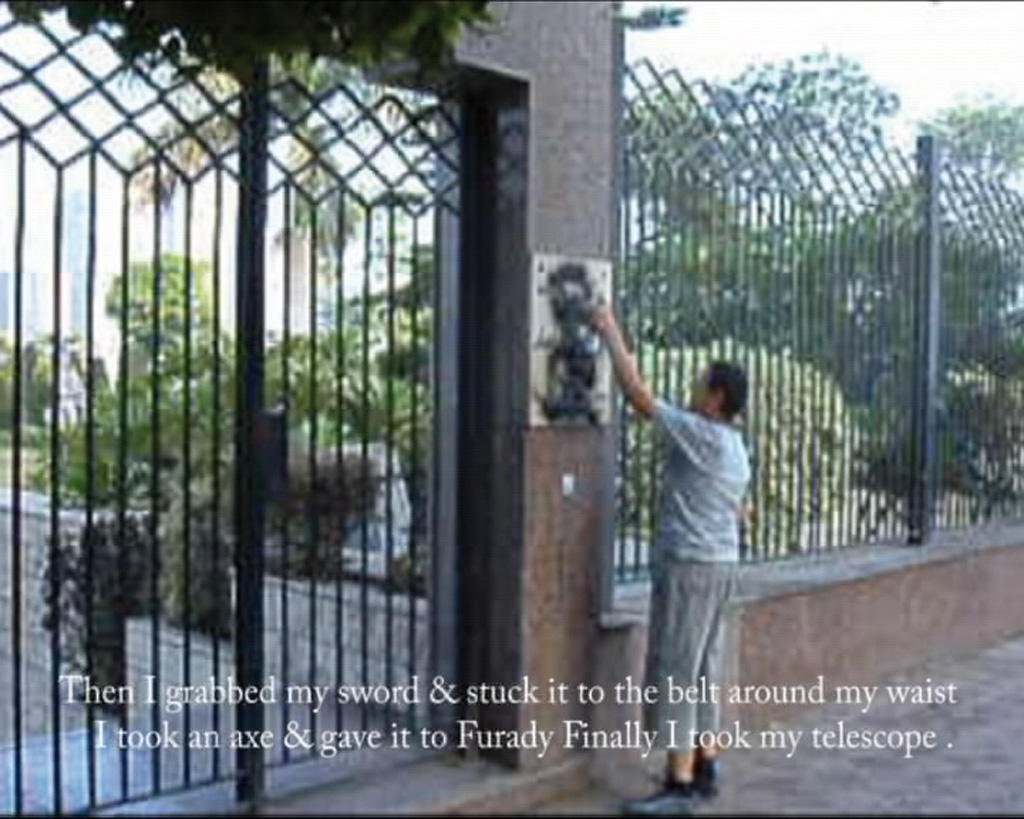

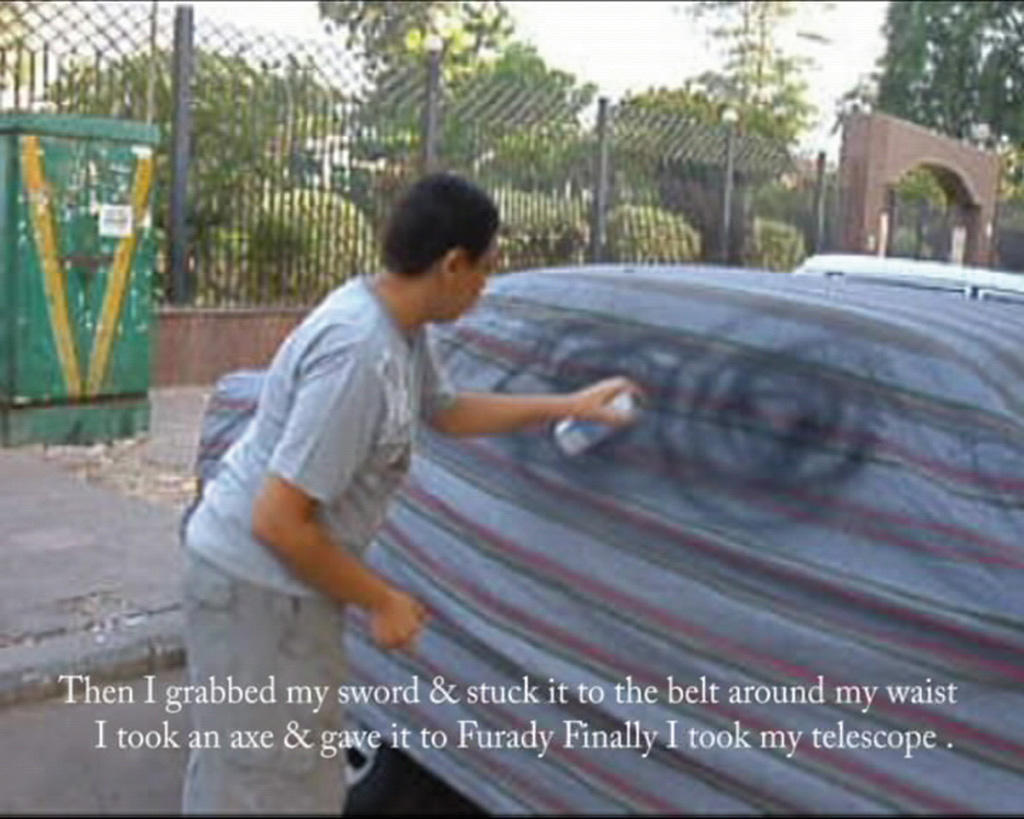

Near 3m Hassan, a TV set on top of a podium played and replayed Lotfy’s A Letter to a Lover. A chubby prepubescent boy, a sort of archetypal naughty kid, ran around with a can of spray paint in a largely concrete, lower-middle-class Cairene neighborhood. Despite the demographic density of such areas, the boy was apparently unwatched. If you looked hard, the strangled sunlight suggested early-morning filming. The boy was both cowardly and delighted with the minor crimes he was getting away with.

The simple comedy was complicated by a female voiceover repeating in Arabic a line taken from Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe: “Then I grabbed my sword & stuck it to the belt around my waist. I took an axe & gave it to Furady [sic]. Finally I took my telescope & climbed to the top of the hill with Furady [sic] to see how many savages had come this time.” The mysterious alignment suggested some deeper meaning, although what this was remained unclear. The repetition of the voiceover was soothing, like a mantra intended to accompany some personal ritual. Were we watching one boy’s game of men and savages? Was this boy a Crusoe or a Friday or a Carib? Were the delinquencies of amateur graffiti so different from those dreamt by other overgrown schoolboys of an earlier age, who were more likely to have actually read Robinson Crusoe? The caption-writer has misspelled “Friday” but this boy got the idea, and so did we.