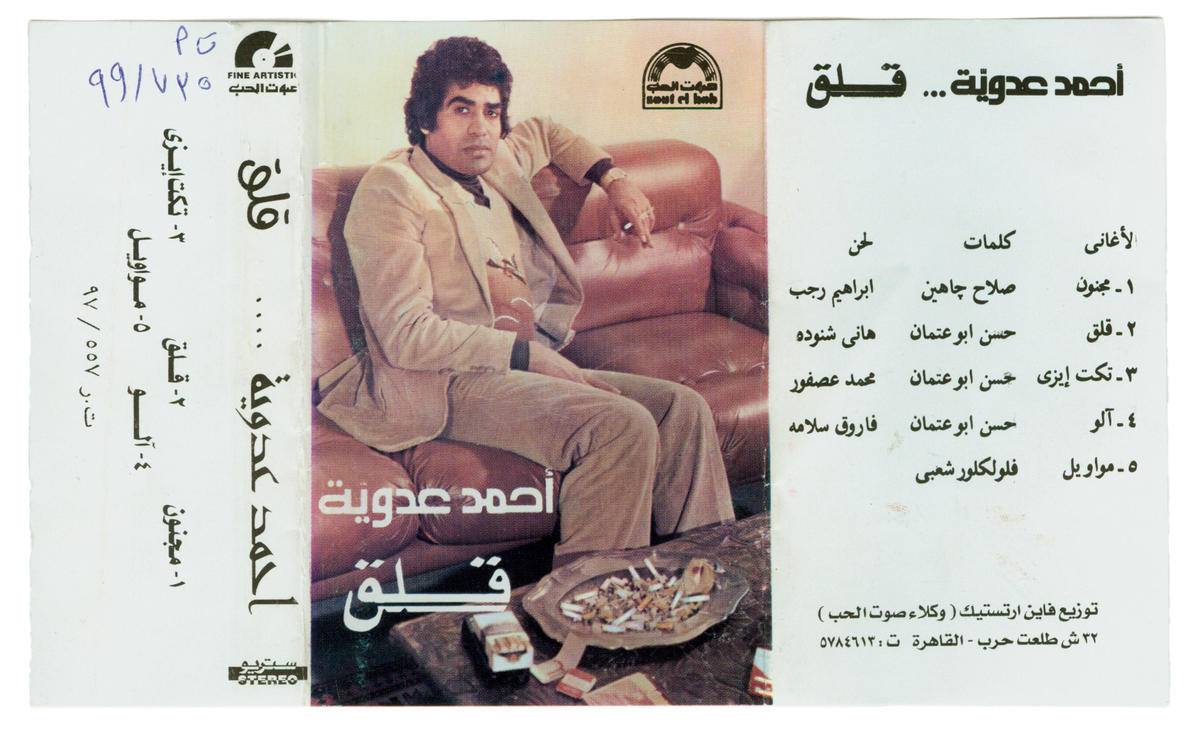

Something is hidden here. Behind this pose and its accoutrements lies an enigmatic moment, an eternal wait, an anxiety. The man in the brown corduroy get-up calmly stares back at us from a hot sticky late-’70s Cairene summer night. In the return of his gaze we become implicated — as voyeurs, witnesses, and actors in some grand existential melodrama. This man, a certain Ahmed Addawiyya — mawwal legend, shaabi phenomenon, runaway superstar — is the same man who once single-handedly, and quite unintentionally, threatened the very foundations of official Egyptian popular culture.

Part of what made Addawiyya seem like such a threat to the intellectual establishment lies in his ability to wed the seemingly innocuous lyric with the poignantly ambiguous. For he not only speaks a street lingo, he embodies it. It is a language that by necessity has to accommodate as much as endure, a place where form becomes function and risk becomes reward. And, as opposed to the staid folkloric primitivist and ultimately racist image of “the local” and “the popular,” this is no eternal or essential static moment. What we have here is an image of a social structure laid bar — not as a rational analysis but as the compulsive enactment of a code.

Ala’ (anxiety), boldly emblazoned on the bottom half of the cassette tape, is both a banner under which this icon operates (an anxiety about positions in a stratified yet fluid world) and a description of an image printed on the cover of the album. It is both surface and depth. Metaphors are here transformed into imagery. Addawiyya’s portrait on the cover is not just the image of a singer; it is a state of being. A secret infused with the pathos of nights that offer redemption and days that mark time. Are we to aspire to his condition? Or are we to sympathize with what he offers us, through a lifestyle that never claimed the simplistic naive “liberation” of western popular culture but rather saw itself as part of a struggle? One which (no utopianism here) is purely based on self-interest?

Machismo and narcissism lie wounded here, deeply melancholic about their fates. However, melancholy and vulnerability are only enhancements of that machismo; “the wounded” is here a specific understanding of manhood. The setting is of course clearly nocturnal — a harsh neon-lit room, one in a series of similar rooms that extend through the loaded homes of this city. In this room we witness the romanticism of acquired cash, the new elite that arose from the amoral streets of negotiations, deals, corruption and petrodollars. The irony, of course, is that the economic reform policies of the Sadat era which further polarized Egyptian society — pushing large segments of the lower middle class into the swelling ranks of the urban proletariat — also formed the backdrop for the birth of class conscious shaabi musical culture and its epitome, the Addawiyya phenomena. The survivors of Sadat’s open door policy were by necessity street savvy, cynical and driven.

Anxiety in the case of someone like Addawiyya (the sign floating around popular consciousness, not the man of flesh and blood) is not only the mark of a specific position, a way of looking or being understood, but rather an essential part of this phenomenon and how it articulates itself. Where cultural productions function as layers of shared consciousness — where the city is translated into its culture—an image of what is essentially fleeting — a myth lost and twisted, abused and abusing. When Gramsci in his own elitist terms spoke of an “organic intellectual,” he might not have been aware that maybe the closest it is possible to come to such a concept is through a popular that is not pop, an unconscious radicalism. It thus comes as no surprise that such a self-confident, indulgent expression of a popular consciousness (one in which lyrics swing from rigorous moral imperatives to the pleasure of ambiguity) got blasted — both by bourgeois critics and the so-called defenders of political integrity. There is a great fear of a class-consciousness that functions within its own signifying system, a class-consciousness that has not been tamed and moralized by utopianism, but one that wears its vulgar and selfish impulses with pride. This fear of what lies around the corner, of the collective repressed, is actually the fear of what allows us the ability to speak about collectives in the first place. This is a fear of a weapon that knows not itself.

That moment is where the alienation of class anxiety is played out, is the enchantment of an aggression made sweet through wit and play. And if this is not revolutionary music (in the narrowest, most self-conscious rhetorical terms) it is something much more, something that bears its wounds as portentous signs. What we have here is an image on an album cover that functions as an enigma circulating through the normalized, and thus potent, channels of commodity and commerce. It is an object that is decoded whenever it encounters its consumer, the surplus of a specific economy of meaning—its discomfort, its counter, and its ally.