I was going to write about Dr Mike’s butt. It’s one of the best objects in the world — the kind of thing that makes people want to start a new religion. But Dr Mike’s ass in my face is long ago. His real name isn’t Mike, and the guy’s only a doctor in the loose sense of healing that Marvin Gaye crooned about in a still-great song. Mike’s one of the two best I ever paid for. His smile was calming, but his rear was a better catholicon.

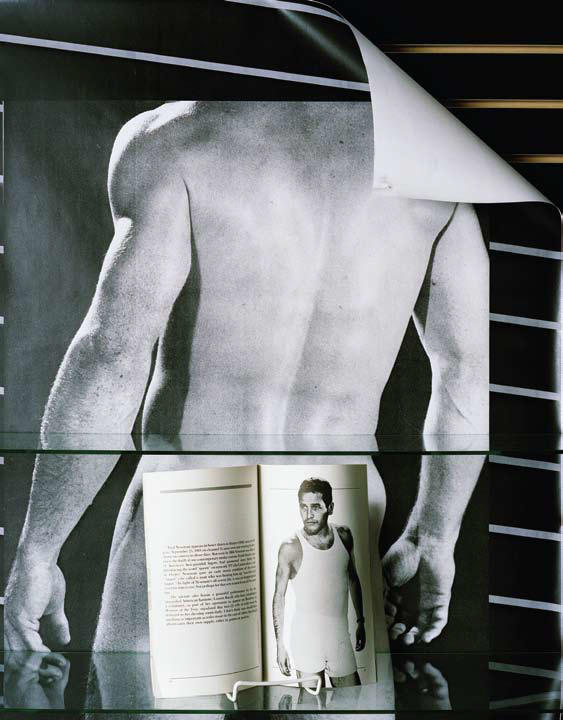

An opened book, spread on a table, has its buttlike qualities: two raised domes, a gutter, a smooth expanse of surface to be “read.” (I don’t recall Walter Benjamin ever mentioning those aspects.) In more relocations than I care to count, books are the only things I’ve bothered to transport. When I first moved out West, to Portland, Oregon, I shipped seventeen book-filled boxes by UPS; two suitcases with the rest of my belongings came with me on the plane. Although the idea of divesting myself of my library has a certain appeal, I can’t imagine living anywhere without a stack of books by my bedside.

Right now, only two kinds of books appeal to me: fine copies of things deeply out of print and the brand-spanking-new. Two such top my bedside stack.

Boyd McDonald’s Cruising the Movies: A Sexual Guide to “Oldies” on TV (1985) still teaches me more about the uses of sex as a goad to thinking than any other tome. An elegantly louche photo by Joseph Modica of a guy wearing nothing but a jockstrap and a studded bracelet graces its cover; the dude is stretched out on a bed—legs casually spread, furred butt bared—in front of an old television set, gazing at the lady with the torch whose appearance opens every movie from Columbia Pictures. McDonald lived an admirable life of unassimilating faggotry. In his sharp obit for the Village Voice, Vince Aletti wrote:

Boyd McDonald, who died September 18 of lung cancer in his room in an Upper West Side transient hotel, was memorialized by his surviving family in a Times death notice that must have surprised those who knew him as the angry old man of gay sexology. “Born July 11, 1925, in Lake Preston, SD,” it reads. “He served in the US Army in World War II, attended and graduated Harvard University. Upon graduation he worked for Time Magazine and IBM Corp. He pursued freelance writing up until the time of his death.” Cranky, brilliant, and hilariously misanthropic, McDonald didn’t just leave the straight, corporate world in 1968, he scorned and ridiculed it, first from the platform of the occasional self-published pamphlets he called Straight to Hell/The Manhattan Review of Unnatural Acts, then in the pages of his many STH anthologies. Though the bulk of McDonald’s publications are given over to rigorously edited letters from readers describing their sexual experiences (typical headlines: “Boy Scouts Line Up for Blow Jobs,” “I Like to Swallow Cum,” “Another Married Man Wants Some Dick”), their genius lies not in his slogan, “The truth is the biggest turn-on,” but in his mix of pissed-off politics and radical raunch.

Fifteen years later, truth still has its appeal; finding it is another matter entirely. Certainly it is no longer in any way coterminous with what’s currently billed as reality. Within Cruising the Movies, a reader will find acute observation, cinematic and political, rendered in taut, funny, and always intellectually provocative prose. McDonald reckoned with the poetics of sex. In “Cruising Broadway,” he snares the ripe thrills of the now mostly long-gone male sex theaters in the Times Square district while demarcating the class consciousness of homosexuality, noting that “homosexuality is the only culture I know of whose queens are middle-class and whose commoners are upper-class as well as lower-class.” He continues:

It takes a higher degree of intelligence than that possessed by the wax fruits and artificial flowers of the middle class, including the educated middle class (for education has nothing to do with intelligence), to know that the Judeo-Christian culture, and the ways in which men achieve dignity and respect in it, are, in a word, shitty. In the long run, the only real dignity and respect come from the simple truth, including the truth of sex.

That word, again. It leads him to wonder about bodies and silence, in a paragraph that is as bawdy as it is ominous:

I wonder if any impresario in this branch of the theater has ever thought of just putting his boys on stage, one after another, and having them strip and play with themselves in silence instead of copying the traditional female format of dancing to music. If the boys would simply undress and play with their dicks, balls and assholes, as they do at home alone, it would reduce the artistic interference of the theater and enhance both the audience’s and the performer’s experience of, respectively, voyeurism and exhibitionism. Such a format could simulate the experience—one of the most enjoyable available in cities with cluttered housing like Manhattan—of looking into a boy’s or a man’s bedroom when he undresses.

Both voyeurs and exhibitionists are admirable, and need each other, and give each other great pleasure. Indeed, the terms “voyeur” and “exhibitionist” are not really necessary; all men are one or the other and most men are both.

Blanchot never bettered this. McDonald’s prose cruises the murmuring at language’s outer reach, fixing on the blankness and silences that give rise to what gets called, in other contexts, poetry.

The other book on my bed stand is, in fact, a book of poems. In swank hues of turquoise and pink, a pixelated grab provides the cover image of Jon Leon’s brilliant new chapbook, Right Now the Music and the Life Rule: a man sucking on the melony boob of hand nuzzles her other breast. Some even more explicit action in black and white makes up the back cover. Language and silence—modulated by the fashion and entertainment industries pushing and pulling on “personal” desire—drive Leon’s poetry, which often takes the form of seemingly matter-of-fact notes in short paragraphs. He negotiates the erotic tensions between how bodies appear and what is thought about them; between, as McDonald suggests, the exhibitionist and the voyeur, transfigured into writing and reading. The names of models, fashion houses, and designers; the words for specific items of clothes (“unitard”; “track breaker”; “short-shorts”); textures, scents, and effects of light—noting these fineries as they allure in magazine editorials and ads might seem alien to whatever poetry is sadly too often thought to be (pious? tedious? abstract?), until it’s recalled that both Mallarmé and Wilde clocked time editing women’s fashion magazines, not to mention Barthes having stitched seam to seme and alerted anyone who cared to the jouissance of midriff, textual and otherwise. McDonald found in the male strip club a suitable zone for an exacting disquisition on class; Leon uses glamour mags to formulate an aesthetic treatise dressed in the apparel of poesy.

Peyton Flanders

If you call +1 888 977 1900 you will reach Prada. Prada is going to go public soon I hear and I know their stock will be valuable. Anonymous is wearing a black dress but mostly she is wearing a Prada bag which really jumps out at you. The bag seems like it is almost as big as the girl. I love girls. She is standing against the car and looks disheveled. Her hair is all split up and her face is ghostly, but although she looks like a hooker she remains infinitely desirable. Behind her it looks like a fire is blazing but it could just as easily be city lights. I picture this one at the point abandoned by a young beau. The bag is great. She has dark circles under her eyes. She radiates a gothic sensuality. Everything in the world is permissible and this captures all possibility.

“Quelque chose comme les Lettres existe-t-il?” asked Mallarmé. (Something like literature, does it exist?) Here it exists in the economic dissolve of information (Prada’s toll-free corporate telephone number; its stock status) into the transaction of products and those who hawk them. This becomes a meditation on how taste is formed (“I love girls”). But in a world in which the product (a Prada bag) almost overtakes the girl, the look of the human turns “ghostly” as one human abandons another. In the final line, all is “permissible”—but is it the permissibility (of abandonment, objectification, human value) that provides the antecedent for the “this” that captures everything possible; or does the pronoun refer to the girl’s gothic sensuality, her ability to change, emote, strike a pose, or be abandoned, while all the bag can do is remain “great”?

The text takes its title from the name of the murderous nanny Rebecca De Mornay portrayed in The Hand That Rocks the Cradle (1992), becoming a gloss on the perils of romance as it makes available other ways of desiring, alternatives to family monogamy. Looking “like a hooker,” the muse is not trashed or used up but “remains infinitely desirable.” Right Now is an ode to the muse (of truth, of Marianne Moore’s paradoxical poetic “usefulness”) in its various guises—as Prada girl or, in other poems, Elizabeth Taylor, or an anonymous male model who conceptualizes a “sans-serif lifestyle.”

All of which might make Leon’s work sound very serious, which it is, but misses its fresh fun. The fun arrives by way of his almost deadpan tone and by what he doesn’t, won’t, or can’t spell out (“I can’t describe the boredom in this picture it is so hospitalesque”). “An indoors type who is against nature,” the narrator—silence’s speaker, absence’s watcher, glamour’s grammarian—listens to Eric Burdon, Jens Lekman, and David Bowie (circa Heroes); he’s also the observant type who gets up and changes “the music because this one requires a whole new attitude.” As it happens, “this one” could be another handbag, another “anonymous” tropical beauty who has caught his attention, or the poem that’s being written and being read.

Huysmans wrote Against Nature to bring about and claim an attitude. He served a cocktail of artifice, spiked with hallucinogenic venoms, to modernity, right around the time Manet mirrored the zeitgeist in the come-hither discombobulation of the FoliesBergère. McDonald caught the worth of sex on the street, or wherever, as AIDS began to take its toll. Leon writes a “vivid index” of what being against nature might look like now. The book, independently produced, is the way he finds best to frame his pleasures and his objections.