Istanbul

The 12th Istanbul Biennial: Untitled

September 17–November 13, 2011

There was so much to love in the last Istanbul Biennial that it’s strange now to remember how irritating it was to experience the exhibition six months ago. In the time that has passed, the biennial has closed, the catalogue has been published as an afterthought, the curator of the next edition (Fulya Erdemci) has been announced, and some of the better works installed by the curators Jens Hoffmann and Adriano Pedrosa have been picked up for public engagement in more generous and capacious shows.

When “Untitled (12th Istanbul Biennial)” opened in September, it seemed as though Hoffmann and Pedrosa were making an interesting tactical move that would give some direction to the unsettled fate of the global biennial format, even if the exhibition was likely to end up as an example of what not to do (conservative cynicism is a terrible response to radical naïveté). At this point, though, the legacy of last year’s biennial looks more like that of a rudimentary exercise in how to play it safe than a meaningful experiment.

Still, the premise was promising — hinge the entire thing on the work of a single artist, and not just any artist, but the late Felix Gonzalez-Torres. Over the course of a short and tortured decade, from the late 1980s until his death in 1996, Gonzalez-Torres perfected a language and a process that turned ephemeral everyday materials into piercing poetic gestures. A diminishing pile of candy equaled the weight of a lover’s disease-stricken body. Two synchronized office clocks conveyed the intimacy of sharing a life. A photograph of an unmade empty bed on a public billboard broadcast heartbreaking loss.

Hoffmann and Pedrosa effectively borrowed Gonzalez-Torres whole, and, after breaking down various pieces from the history of his work, they built their curatorial armature, deduced their themes, chose their title, and selected their exhibition’s color palette. Although they decided to show not a single Gonzalez-Torres piece, they argued that the biennial was suffused with his disembodied presence and breathed his spirit. The problem was that one (or two) cannot force an exhibition of some 130 artists into a relentless and unforgiving grid of temporary cubicles and make any claim on behalf of a supple and searching practice.

Moreover, what the curators extracted from Gonzalez-Torres — a balance between politics and aesthetics, a concern for history, memory, identity, violence, and desire — they could have found anywhere. The biennial lacked not only his tenderness but also his intelligence. It had the strange effect of taking a number of great artists — some of whom had lived and died before Gonzalez-Torres was born — and plunging them into to his shadow for the sake of a structural conceit. It was absurd to pin this much on a dead artist who was so universally and uncritically adored. The biennial would have honored him more if it had opened his work up for debate.

“It could be said, in both praise and disdain, that his works are ‘perfect,’ that they are so formally and conceptually airtight as to be unassailable, even that they anticipate their amnesiac embrace today,” wrote Joe Scanlon in a blazing reassessment of Gonzalez-Torres that ran two years ago in Artforum. “And yet despite this hermetic environment, I can’t help but wonder what he would think of the ease with which his artworks are administered today, or how he would feel about the assumptions that have ossified around them. If his work is going to remain vital and relevant, then it is time for those assumptions to be vigorously challenged.”

Many better critics have already expressed the ways in which Hoffmann and Pedrosa exerted too much curatorial control over their exhibition. In laying down a strict framework that must have looked faultless on paper — five thematic exhibitions surrounded by related clusters of solo presentations — they left little to no room for useful accidents, or for the dangers and delights of leaky meaning. Maybe it’s too much to say that this edition of the biennial was disdainful of its city (by holing itself up in two quayside boxes and turning its back on Istanbul) and hostile to its artists (by so forcefully containing their work, neither allowing nor pushing them to say more) – but then again maybe not.

Perhaps the most frustrating thing about the biennial was its success in making so much good work complicit in the total aestheticization of politics. Gonzalez-Torres developed a way of speaking the unspeakable in a very particular era of political crisis and culture war in the United States, not least marked by the Reagan administration’s criminal neglect of the AIDS epidemic. Using Gonzalez-Torres as a point of departure, restaging Group Material’s AIDS Timeline (1989), showcasing the Ardmore Ceramic Art Studio’s ingenious public service announcements on vessels, plates, and figurines — none of this answered the question of how or why this historical period was being revisited and revived in 2011. This aimlessness made the biennial — occurring in such close temporal and geographic proximity to political and socioeconomic upheaval around the world — feel like it was on the wrong side of history, a gesture in support of the market, the institution, the status quo, the large-scale perennial exhibition as a handy tool in the vast neoliberal kit.

In taking only forms and broad themes into consideration, Hoffmann and Pedrosa lost the potential for committed political engagement and were left with so many bits of paper, shredded documents, and ponderous books (Marx, Borges, Debord) treated as props. In some cases, they seemed to get the emphasis of a work all wrong. In others, they chose bad work over better. What makes Wael Shawky’s Cabaret Crusades: The Horror Show File (2010) so wonderful and weird is not the fact that it is about “history,” but how the crude fusion of 200-year-old Italian marionettes and Amin Maalouf’s The Crusades Through Arab Eyes emits such an erotic change. Had the curators read Gonzalez-Torres’ chart of his partner’s failing immune system as being about loss and the degradation of a body rather than a line and the history of abstraction, then they might have selected Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige’s mesmerizing film from the installation Lasting Images (2003) instead of the lesser 180 Seconds of Lasting Images (2006).

For the past few years, the young photographer George Awde has been working on a gorgeous series of large-scale, color-saturated photographs, all labor-intensive images that capture the fragile community that a group of young men — Syrian Kurds, Iraqi refugees — have formed in precarious circumstances in Lebanon. The two images from the series that appeared in the biennial were not only the weakest of his works (but they fit the theme), they were also completely dwarfed by a bombastic installation by Elmgreen & Dragset. Rula Halawani’s powerful photographs of black-and-white Palestinian landscapes, capturing the scars of occupation and giving archival practice a new twist, could have used their own room, rather than low placement on an already over-cluttered wall. Marwa Arsanios and Jonathas de Andrade both had vast, prominent spaces for their installations delving into urban myths and failed modernisms, but neither really did justice to the individual fullness of their projects (grouping together works that looked alike was a particularly irksome tick of this biennial). An altogether different problem: Akram Zaatari’s video Tomorrow Everything Will Be Alright (2011) worked beautifully on its own. An artist of his stature didn’t need a random sampling of past projects — illegible and incomprehensible in this context — to bolster his participation.

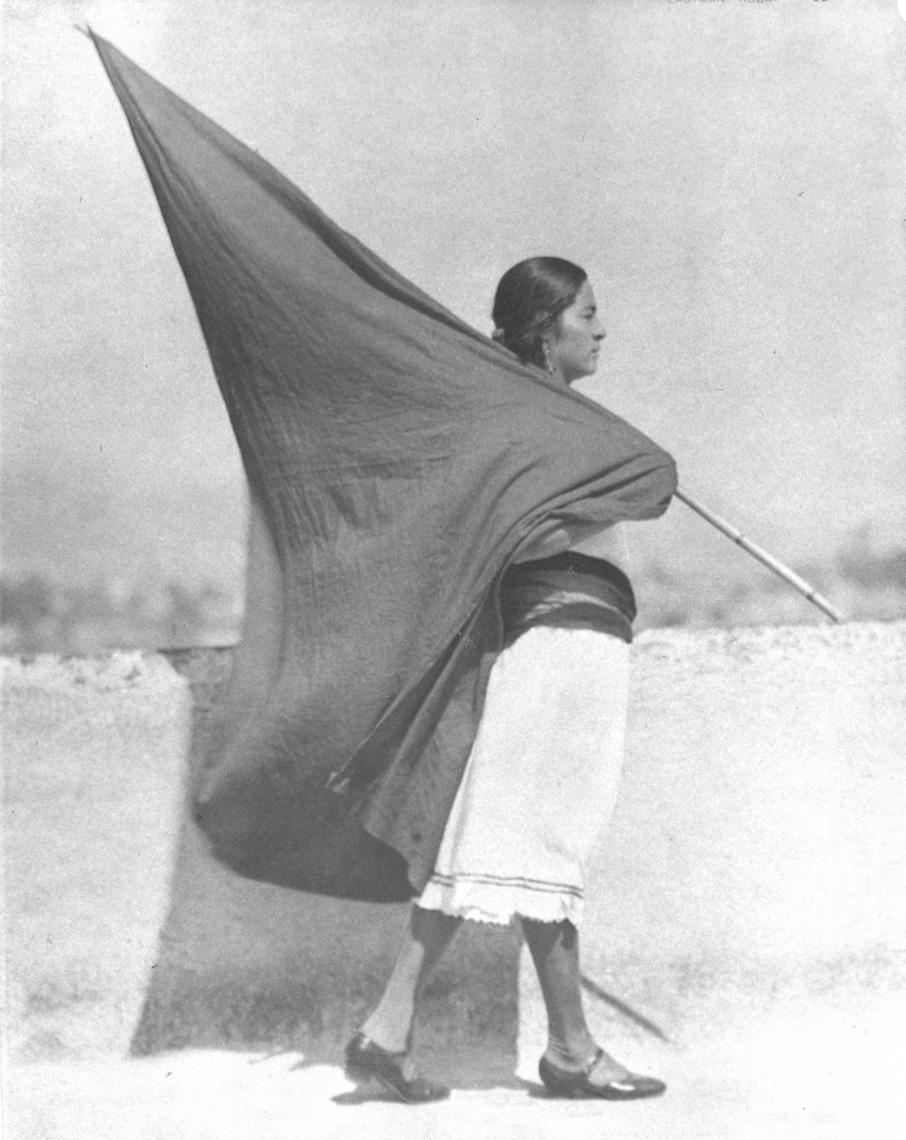

This is not to say the exhibition wasn’t full of wonders — Martha Rosler’s Bringing the War Home (1966-72), Tina Modotti’s revolutionary photographs, Dora Maurer’s Seven Rotations 1–6 (1979), Mathew Brady’s images of the American Civil War, Hank Willis Thomas’ terrific series I Am Amen (2009), and Lygia Clark’s tiny hinged metal sculptures. I loved seeing Geta Brătescu’s fabric abstractions, but I learned much more when I saw her work in the New Museum’s “Ostalgia,” where the presentation was far more satisfying. And that’s the thing. The curators of this biennial made such a fuss about refusing to divulge the list of participating artists before the opening, and yet the exhibition was essentially itself a list, a roundup, an arrangement of names with mostly small-scale works standing in to represent them. At least, at this point, it’s pretty clear that opportunities to better see their work will happen, they’ll just happen elsewhere.