London

Walid Raad: Miraculous Beginnings

Whitechapel Gallery

October 14, 2010–January 2, 2011

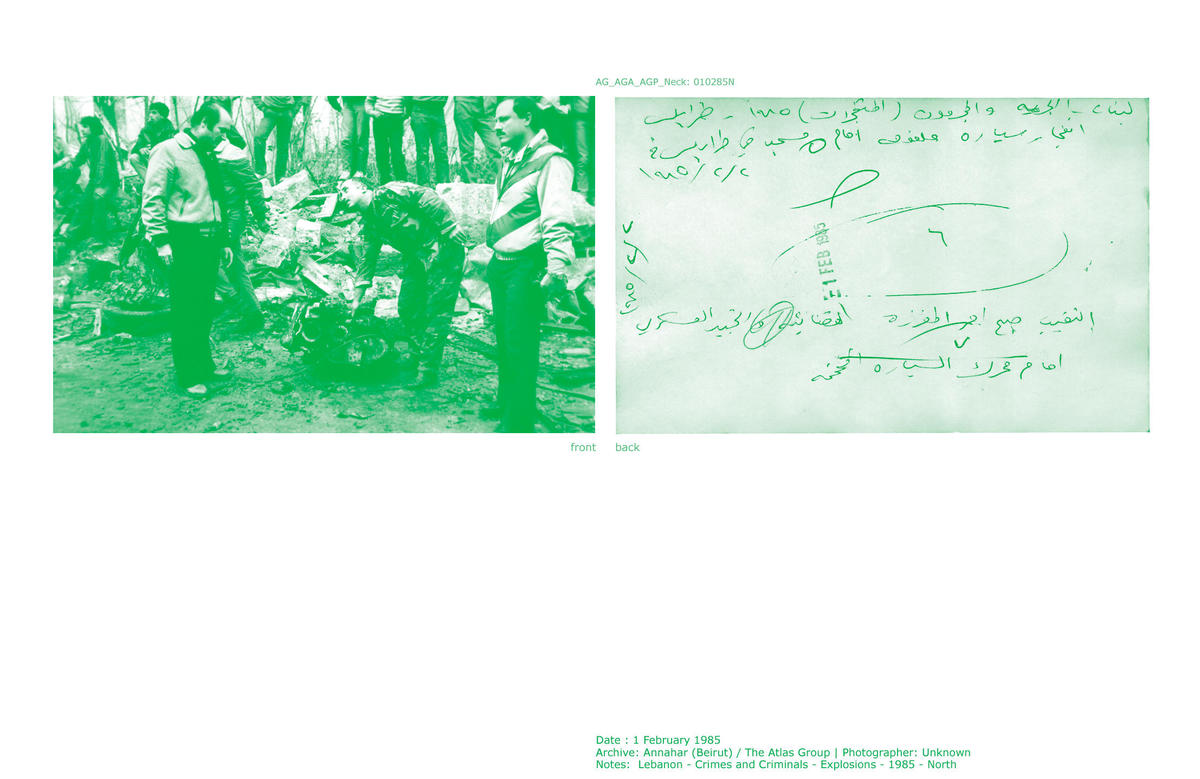

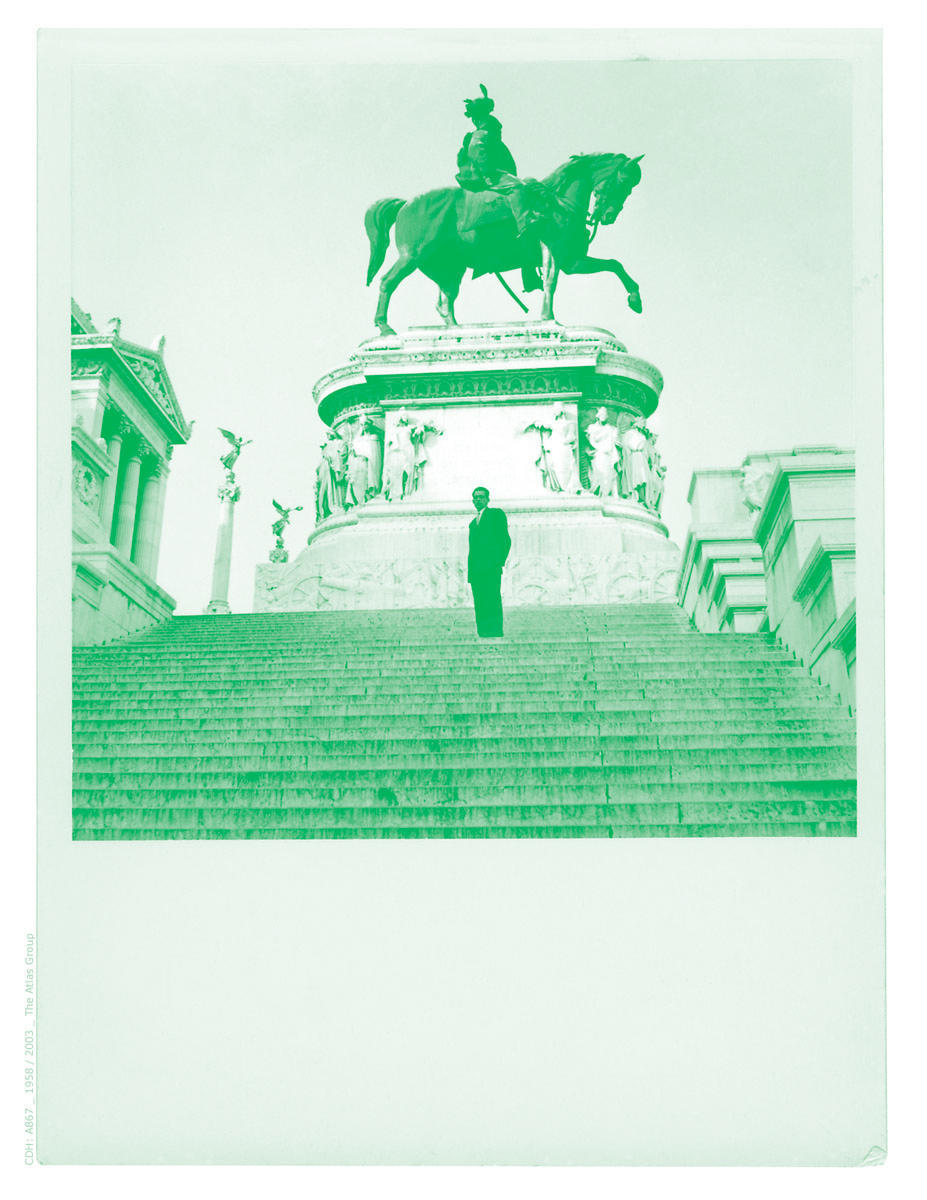

More than once, I visited Walid Raad’s retrospective with art professionals and saw them scoot around its opening phases — devoted to Raad’s best-known work, The Atlas Group (1989–2004), his complexly dissimulating, copiously detailed array of “documents” relating to the Lebanese civil war between 1975 and 1990 — at a pace that suggested overfamiliarity. (The first time around, I joined in.) Ironic, no? You devote your artistic practice to holding images and the historical events they open onto in perpetual suspension, resisting the neutering effects of both historical amnesia and the unthinking consensus that documentary materials can create around past events. You consequently influence the archival and fictional turns in recent art. And as a result your work comes to be treated as a known quantity, as open to second looks as the average whodunit. More ironic still, those viewers who didn’t even ascend to the show’s second floor would, had they done so, have found Raad almost seeming to anticipate such a response. Here, at the center of his latest project, Scratching on Things I Could Disavow: A History of Art in the Arab World (2008–present), was a miniature architectural model of a gallery interior (Beirut’s first “white cube” space, Raad writes), hung with tiny replicas of many of the photographs and videos on view downstairs: The Atlas Group decisively made small.

Raad, an artist acutely aware of how art is modulated by the changeable conditions of reception, speaks here of the depredations of context. In his purposely quixotic accompanying text, he describes being asked to exhibit The Atlas Group in Beirut repeatedly from 2005 onward, refusing, finally agreeing, and then visiting the gallery and being “surprised to find that all my artworks had shrunk to 1/100th of their size.” So, he says, “I decided to display them in a space befitting their new dimensions.” If location can defuse art, so can the kind of hasty categorizing that’s a pitfall of our proliferating art world. At this point, a viewer who has accelerated through ‘Miraculous Beginnings’ might be advised to return to the start, to the nuance, grit, fissuring and poetry discernible in The Atlas Group on 1:1 scale.

Rife with digital tweaking and tinctured with radical doubt, The Atlas Group is a patchwork of factual fictions, its dissembling pointing toward truths concerning ambiguity and subjectivity. Take, for example, Notebook volume 72: Missing Lebanese wars (1989–98), which introduces a narrative in which “the major historians of the Lebanese wars were avid gamblers.” Volume 72 is, in this regard, an assiduous if slightly pushy bit of scene-setting concerning historical certitude.

Here, notebook pages — in which photo-finish images of horseracing are surrounded by fervent penciled notations — stand as “evidence” of historians betting, significantly, not on accuracy but on gradations of inaccuracy: “precisely when — how many fractions of a second before or after the horse crossed the finish line — the photographer would expose his frame.” Raad — who, here as repeatedly elsewhere, faked the “proof” — often locates his art in just such a void of final knowledge at the center of a swirl of persuasive detail. See, for instance, Hostage: The Bachar Tapes (#17 & #31) (2000), a video testimonial attributed to Souheil Bachar, who discusses the intimacies, including the sexual ones, of being abducted and detained in Lebanon between 1983 and 1993 with five Americans, all of whom wrote their own accounts of the experience.

Affect and aesthetic pleasure further complicate Raad’s dynamics, as in Let’s be honest, the weather helped (1998/2006–7): photographs of shelled Beirut architecture speckled with overlapping, color-coded, diversely scaled circles marking the location of bullet holes, their size, the “mesmerizing hues I found on bullets’ tips,” and their country of origin. This strategically problematic push-pull of opulent visuality and objective tabulation is redoubled when one experiences these works alongside, say, I only wish that I could weep (2002/1997), a sedulously antiqued VHS-to-DVD compendium for which, we’re told, a Lebanese army intelligence officer deserted his duties (video monitoring of a busy boardwalk in Beirut) once an evening to film the sunset, an accelerated succession of these appearing on screen. In such cases, the usefulness of Raad’s deflected authorship becomes most apparent. The seemingly sentimental is permitted by the maker’s supposedly being not an artist but an official, though we probably know this isn’t true; and the freighted sunsets (symbolic endings that never really end) disarm us anyway, most likely because they don’t feel wholly vouchsafed by Raad.

It’s perhaps no surprise that, following his increased exposure within the art world — and, more widely that of artists from the Middle East — Raad would switch tack and take an aerial view of his art’s absorption into the art system (as in his miniature museum), the idea of a regional aesthetics per se, and the narratives that preceded the current moment in the form of the contested histories of Arab modernism. So ‘Miraculous Beginnings’ divides the earlier works of The Atlas Group from the newer Scratching on Things I Could Disavow, bridging them with Sweet Talk: Commissions (Beirut) (1987–present), a photographic project that takes a catalog by Walker Evans as the template for an extensive documenting of the Lebanese capital. In contrast to Raad’s earlier work, which probes the relationship between representation and meaning-making, the section of Scratching titled “Appendix XVIII” projects into a tentative, slightly maladroit space where — vouchsafing Jalal Toufic’s concept of “the withdrawal of tradition past a surpassing disaster” — another syntax, in this case underpinned by abstraction, is called for. Ranged around the walls, rectangular expanses of primarily single colors are augmented with slim lines of text characterized by styles of obstruction: overprinting into illegibility, translation into foreign languages, rotation through ninety degrees, etcetera. The fact that these abstractions are in fact born of ephemera that the artist assiduously collected from exhibition invitations, catalogs, and art-historical theses on the histories of modern and contemporary art in the modern world is only vaguely alluded to. Perhaps it doesn’t matter, for in this way, their abstraction is physically, and conceptually, complete.

This is finished work that characterizes itself as a starting point, with cohesion, closure and complacency kept judiciously in abeyance. Despite the superficial sense of rupture, however, it’s convincingly contiguous with the artist’s earlier work. The continuity resides partly in Raad’s gravitation toward useful fictions: Appendix XVIII, if you like, is a darkly ludic fantasia wherein the lineaments of art are irrevocably recomposed in the wake of a traumatic war, turning fugitive, inward, gnomic. But ‘Miraculous Beginnings’ also underlines that, at its broadest, Raad’s art consistently concerns itself with how cultures operate when existing languages do not suffice, and how the latter ought not be replaced by something equally authoritative. What this show sustains, and succeeds in conferring from its uncharted end back onto its recognizable beginnings, is an alternative: a singular, paradoxical tone — urgently provisional — that Raad evidently owns.