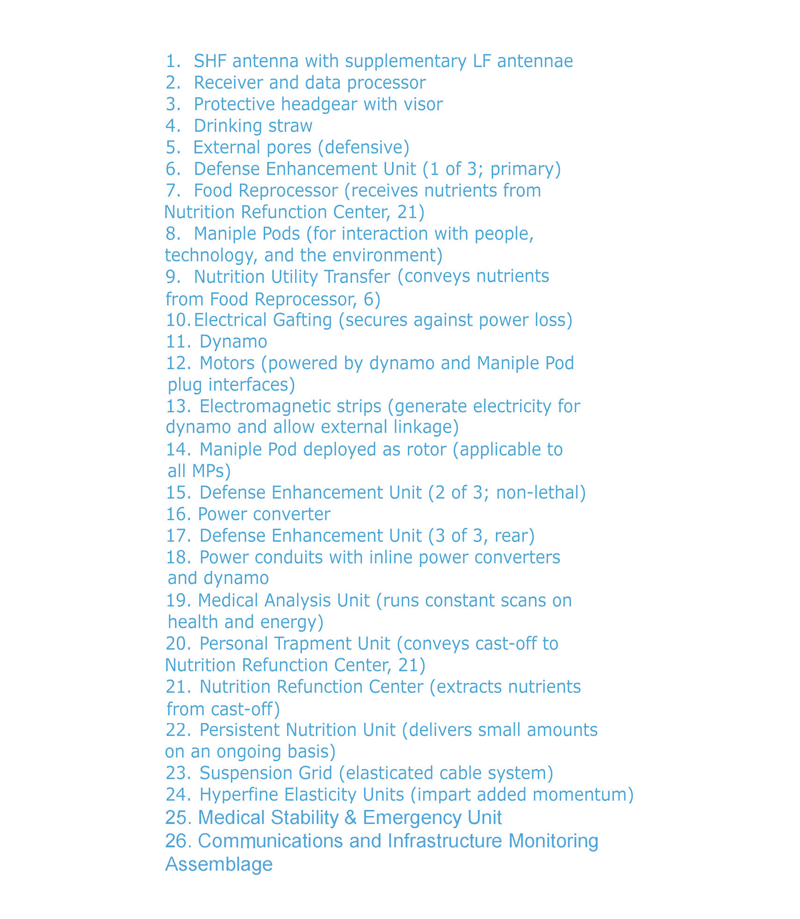

What follows is an abridged version of the speech given by Fred Wolf, a Halliburton representative who spoke at the Lexis-Nexis Catastrophic Loss conference held at the Ritz-Carlton hotel in Amelia Island, Florida on May 9, 2006. With the help of Dr Northrop Goody, the head of Halliburton’s Emergency Products Development Unit, Wolf demonstrated three SurvivaBall mockups, an advanced new technology that will keep corporate managers safe even when climate change makes life as we know it impossible. During the presentation, Dr Goody showed slides, diagrams, and videos describing the SurvivaBall’s many features.

For the integral multimedia presentation of the SurvivaBall, go to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3a3XBnMe5Q_.

Thank you for inviting Halliburton to speak at this conference on catastrophic loss, on this panel on disaster preparedness. A lot of you work with the insurance industry, of course, and that’s why today I want to speak about something that’s a major preoccupation for all of us here, whether in reconstruction, or insurance, or actually any industry — and that’s safety.

And buckle your seatbelts, because we have a real treat for you today. At the end of this talk, my colleague Dr Goody will unveil a mockup of a brand new solution to one particular safety problem, [one] that could one day prove essential to anyone in a position of responsibility, including all of us here.

So. First of all, let’s define our words: what do we mean when we say “safety”? Well, for us in the corporate world, the most essential form of safety is simply the safety to achieve what we need, as we need it, and how we need it.

Whether I’m in reconstruction, energy, manufacturing, or insurance, if I’m taking a risk, I want the government’s hand to be pulling me safely over the obstacles, not laying obstacles in my way. I want to be safe to minimize the risk to my investments as I see fit, without being told what’s right and what’s wrong.

Insurance firms are also concerned with safety, another form of it, a special-case definition: the safety of people. Because their own safety depends so much on that special form of safety, insurance has become quite worried about some grave new dangers to people that we’re seeing in the world around us. I’m talking about climate change and the natural disasters it brings.

Indeed, the numbers could look frightening. In the 1950s, insurance had to pay $4 billion per year for disasters. Now it pays about forty times that, or $150 billion each year. And it’s getting worse; Munich Reinsurance has written that “climatic change will lead to natural catastrophes of hitherto unknown force and frequency” triggering losses of “many hundreds of billions of dollars per year.”

To make things worse, there are some who believe that this is only the start. In nature, things often change very suddenly, and scientists feel that the things we’ve seen so far may be minor compared to what could happen.

For example, Arctic melt has slowed the Gulf Stream by thirty percent in just the last decade; if the Gulf Stream stops, Europe will become just as cold as Alaska.

Or it could go the other way — methane released from melting permafrost could cause a heating cycle, making human life unlivable outside air-conditioned hotels like this one.

Or, as the oceans heat up and expand, ice sheets could slip off Antarctica — meaning most of the earth’s major cities will flood!

Even if none of this happens, some scientists tell us the changes we’re likely to see will greatly increase disease and migration and could exacerbate growing tensions within our societies possibly to the point of civic unrest or even war.

This sort of thinking has even influenced some insurers. Lloyd’s of London has stated that climate change could easily bankrupt the entire insurance industry, and Munich Re suggests it could topple global capital markets as a consequence.

Given the science, these worries cannot be called unreasonable. But panicking isn’t the answer.

If we panic and try to stop climate change, seventy percent of carbon emissions will have to stop. That’ll be a huge blow to our way of doing business: government intervention will become the rule, and we’ll have thrown out the baby with the bathwater.

To remain profitable in a macroscopic loss situation, we must integrate disaster into our global business vision, and not allow immediate dangers to interfere with our general, longer-term concept of safety.

We at Halliburton, for example, assure our safety not despite, but via, the ambient danger — in reconstruction, relocation of refugees, peacekeeping. These arenas are synergistic: where there’s conflict, there’s reconstruction; where there are refugees, there’s conflict; where there’s conflict or reconstruction, there are bound to be refugees.

Sometimes danger presents broad new opportunities. In New Orleans, for example, Katrina pruned the city, removing people from economic black holes and allowing a redevelopment process that’s gratifying for all of us. Although real estate values plummeted immediately following the disaster, much commercial real estate is already over its pre-storm values.

While we don’t suggest that everyone make climate change the core of their business plan, I can personally guarantee you that level heads will always be able to turn lemons into lemonade.

But as Warren Buffet, the oracle of Omaha, so astutely said, you must follow the Noah rule: predicting rain doesn’t count, building arks does.

I can personally guarantee you that we as a society are more than ready to build arks against these conditions — in some cases, we’ve already done so.

Keeping the ark of our interests afloat in a world of increasing disquiet is the job of our defense industries, and they do it quite well — here’s the Green Zone in Baghdad.

Likewise, secure neighborhoods protect us against the unknown in our own societies — this security checkpoint built after the Rodney King riots protects a community on the edge of Los Angeles.

For those of us in positions of responsibility, however, who might have to take charge in a crisis, even more innovative solutions will be needed. We can’t be satisfied with mere survival, but must guarantee, at every instant, the capacity and resources to keep our thumbs firmly on the triggers of progress.

From an insurance perspective, this is more essential than any other safety challenge, since it will guarantee the continuing liquidity of the insured enterprise. And the only way to do this is to maintain a highly sophisticated boots-on-the-ground strategy.

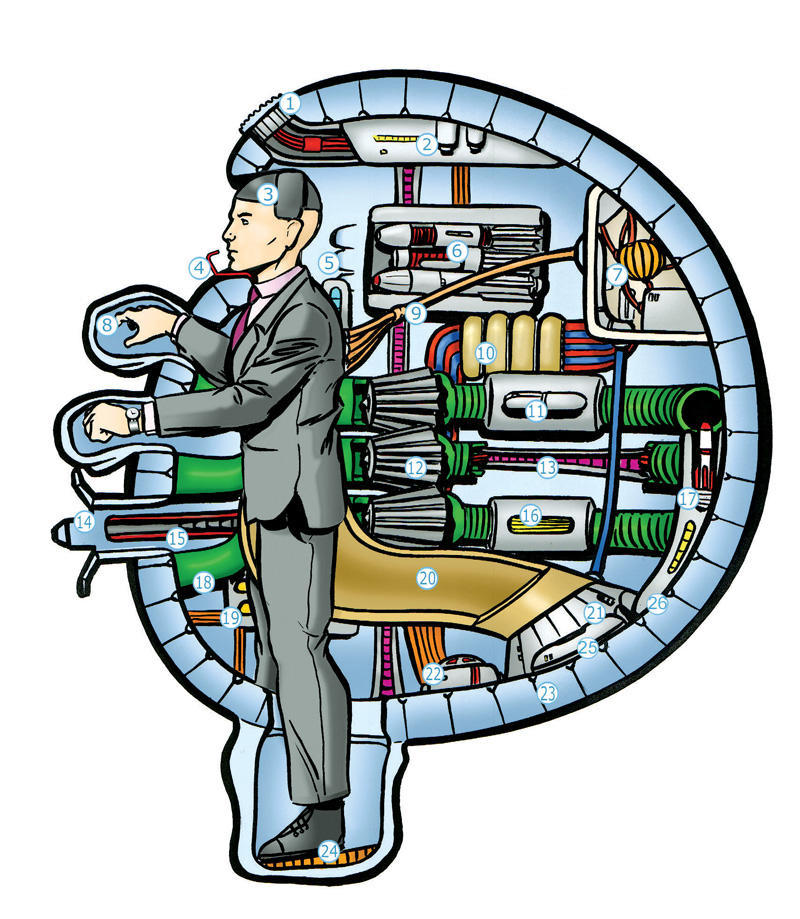

I’d like now to introduce my colleague, Dr Northrop Goody, who’s the head of our Emergency Products Development Unit at Halliburton. Dr Goody will be showing some mockups that his unit has developed, and will explain the unit’s various features.

[Dr Goody calls for volunteers and begins helping them on with the suits.]

As Dr Goody prepares the suits for demonstration, I want you to do a little thought experiment. Imagine you’re sitting in your office, and suddenly you get the reports: there’s a catastrophe. Let’s say it’s a flood with high winds and also some fires, accompanied by an outbreak of dengue, or “breakbone fever.” You’ve been getting the warnings for weeks, but suddenly it’s upon you, and, boy, is it bad.

But you can see that the situation holds promise. You’ve recently invested in equipment that could be repurposed to address water damage. Much of that stock is offsite — in a warehouse fortunately located well above sea level. Also, you recently invested in a new security force that could be redirected to profitably help impose some semblance of order, especially since ten million refugees are threatening to arrive from the next country over, which recently experienced an even worse climate event.

The only problem is, you aren’t sure you can maintain your management structure and data integrity in a condition to safely achieve these results. How will you not only survive, but also continue to function and thrive in the chaos of a disaster?

[Fred Wolf is now put into a suit as well by Dr Goody, and Dr Goody explains the features of the suit. Wolf sums up from within one of the suits.]

Thank you Dr Goody, that was very nice.

I want to end with a sobering note: this isn’t a magic bullet. You all surely have contingency plans within your corporations to deal with climate change disasters — I hope you do, anyhow. But none of that’s worth anything unless your managers survive, and that’s what this is about: the most important form of safety.

We’re going to have a working prototype model within six to nine months, and we’ll be happy to come do a demo in your home offices. I’ll come around and get your business card to put you on the list, but first we’d like to take any questions you might have.