Letter to the Editor

Nazlee Radboy

To the slaughter.

Beirut

Tamara al-Samerraei

Agial Art Gallery

December 2008

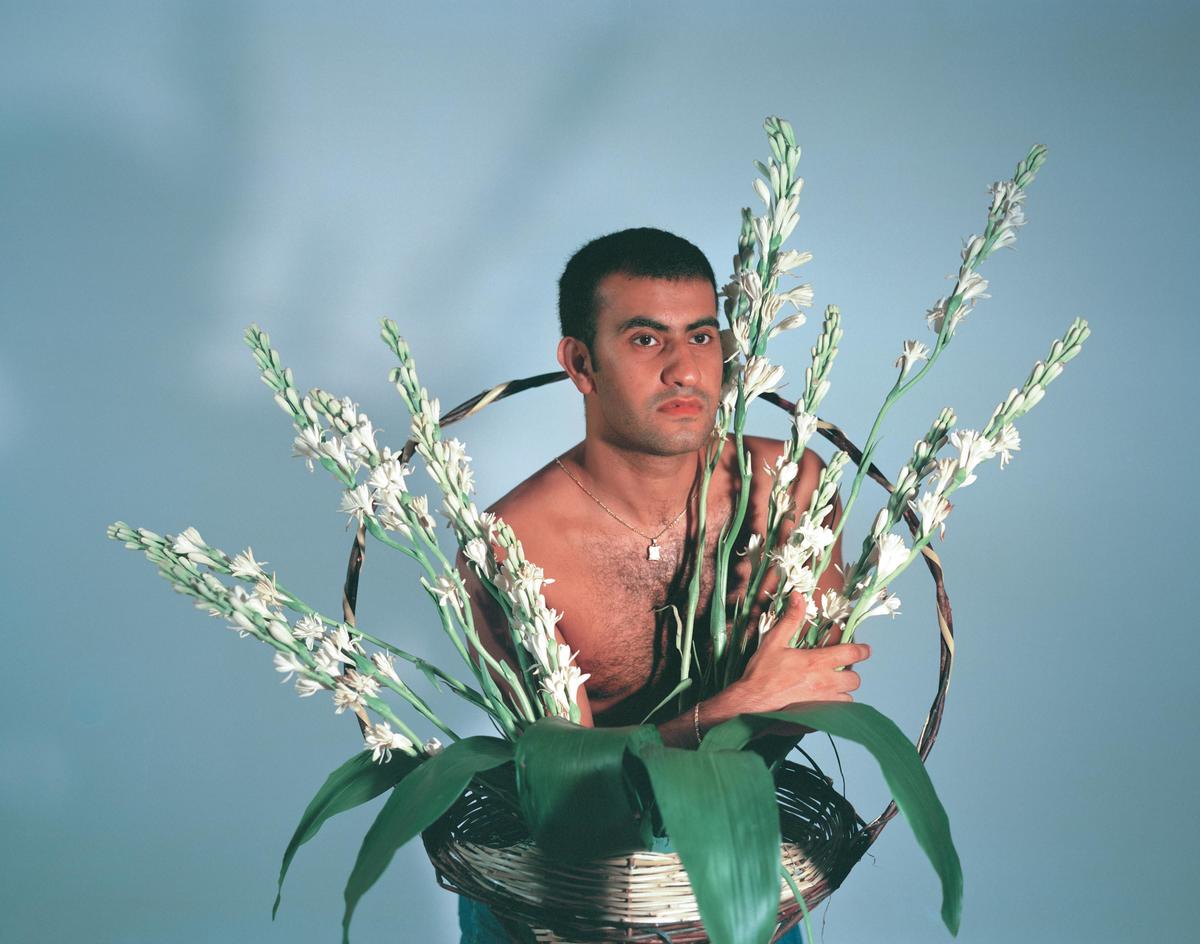

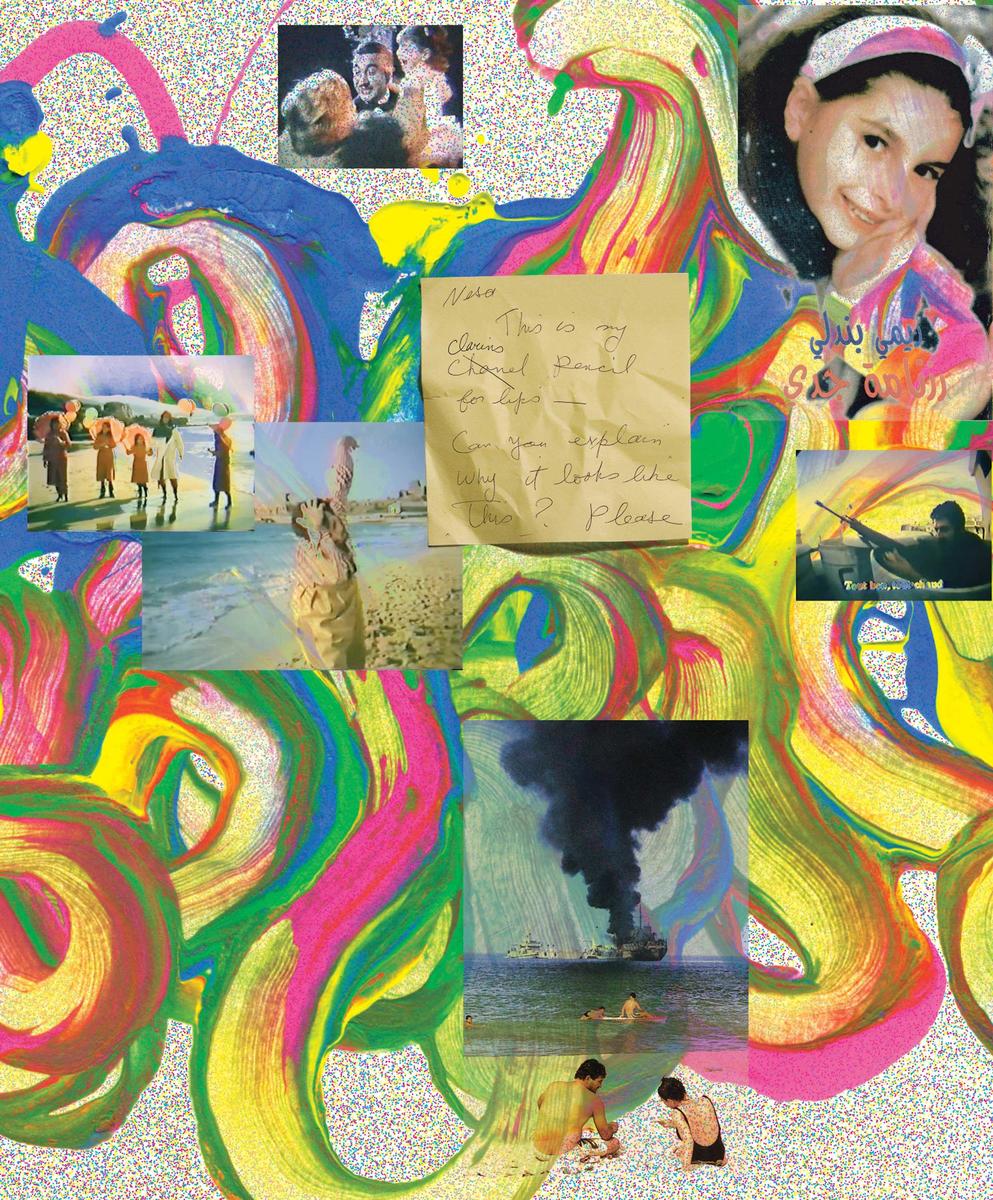

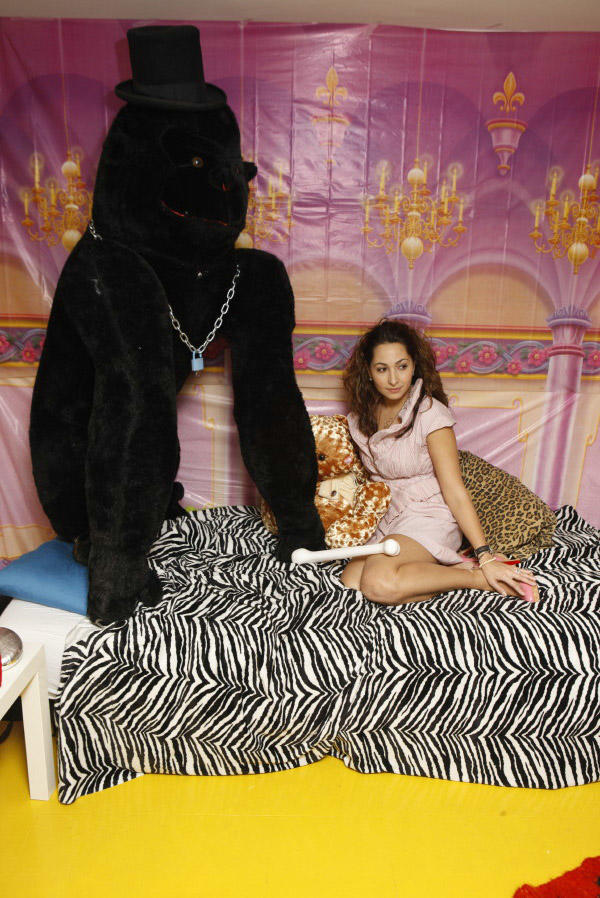

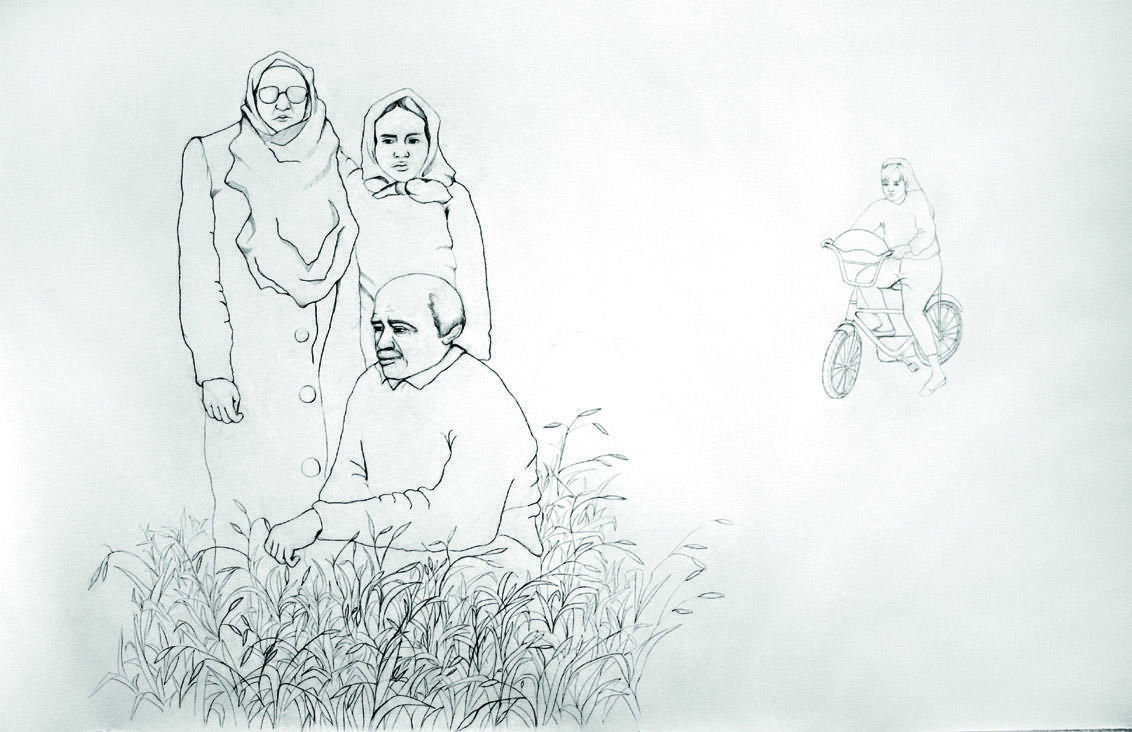

It’s been all too easy, over the past few years, to declare the death of painting in Lebanon. The fey landscapes and drippy abstractions that characterized Lebanese art in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries have been routinely declared irrelevant by a generation that turned to video, installation, photography, and urban intervention instead. Suddenly, however, it seems as if painting is back, with young artists such as Ayman Baalbaki, Taghrid Darghouth, and Zena Assi mounting exhibitions of highly skilled and, yes, socially incisive and politically relevant work composed of retrograde pigments on canvas. Now, the Agial Art Gallery is unveiling a new series by Tamara al-Samerraei, a painter who has also done a fair share of experimentation with installation and video. Samerraei, who was born in Kuwait and has been based in Lebanon for a decade, has already produced a substantial body of work focusing on the faces of girls who are teetering on the edge of adolescence. Her new series takes her painting practice a step further, and the girls have grown up just enough to introduce an atmosphere of sexual awareness, sinister playfulness, and the suggestion of impending danger.

Beirut

Video Avril

Ashkal Alwan

April 2009

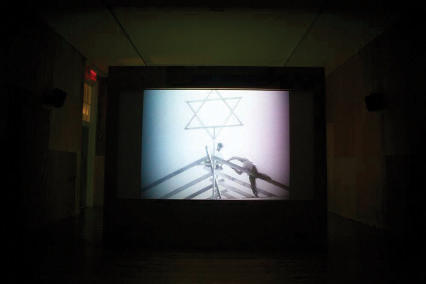

In 2007, Ashkal Alwan staged its first edition of Video Avril in Beirut, promising to turn the event into an annual, international platform for emerging and established artists alike by 2009. The idea for the event was born in early 2006, and its founding motivation was to allow for sustained experimentation with video as video (as opposed to video as a warm-up for film) and to push the codes and rhythms of the medium itself. But when the war with Israel broke out in Lebanon several months later, the terms of Video Avril changed, expanding the presentation to encompass a three-part program of nearly thirty works, many of which were made in urgent, specific response to a particular conflict. The results were mixed, and since then Ashkal Alwan has given the entire Video Avril model a rethink. Seven young artists, including Mark Khalife, Ghayth al-Amin, and Marwa Arsanios, were given grants to create new work for 2009. The works will be completed by April. Whether or not they’ll be screened for an audience remains an open question. This could be read as a retrenchment from the public sphere, or, more generously, as an admission that young talent needs more time to incubate.

Beirut

In the Middle of the Middle

Galerie Sfeir-Semler

November 19, 2008–March 21, 2009

Catherine David has been actively engaged with the contemporary art scene in Beirut for years, having organized the first iteration of her long-term Contemporary Arab Representations project around the Lebanese capital as a kind of curatorial core. But it’s worth noting that while the project’s exhibitions, performances, and seminars traveled extensively throughout Europe, they never made their way back to Beirut (even the Beirut issue of the journal Tamáss never arrived). Certain ideas and discussions, particularly with regard to how the term “representation” was being used, did manage to cross back into the country. But outside of the artists who were personally involved, the Lebanese public never had much chance to encounter — much less consider, respond to, or reflect on — the initiative, and as a result, few in the art world here really know David’s work from firsthand experience. All of that is set to change with In the Middle of the Middle, a group show that David has curated for Galerie Sfeir-Semler. Featuring the work of Jawad al-Malhi, Yasser Alwan, Ayman Baalbaki, Anna Boghiguian, Rami Farah, Joude Gorani, Wafa Hourani, Simon Kabboush, Waël Noureddine, Hani Rashed, Walid Sadek, and Akram Zaatari, the exhibition is definitely not a reprise of Contemporary Arab Representations. Instead, it promises to reveal some interesting links among a disparate group of artists, and to offer some tangible insight into David’s own process as a curator and thinker who insists on the political potential of cultural practice and makes no compromises for the sake of emerging markets, the erotic exotic, or the public relations packaging of the region’s artistic products.

Istanbul

Huseyin Alptekin: Bunker Palas Hotel

Yapi Kredi Kazim Tashkent Art Gallery

February 2009

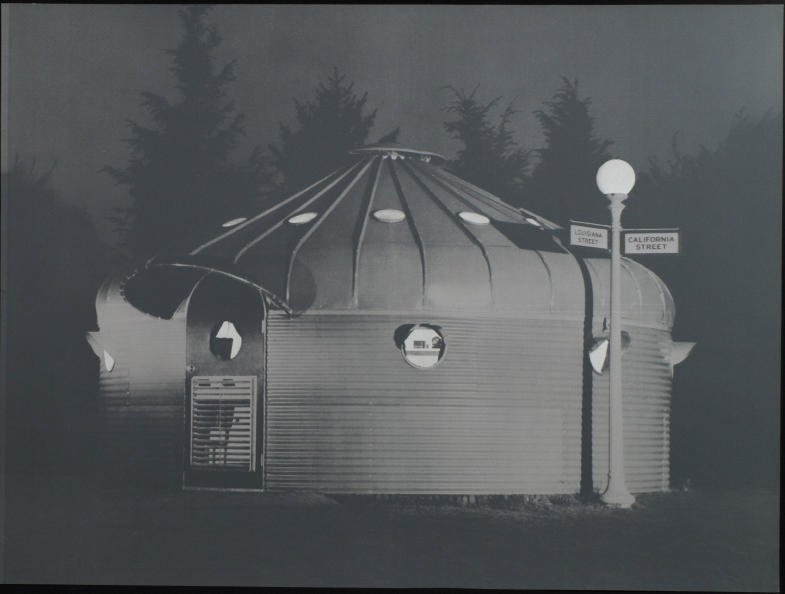

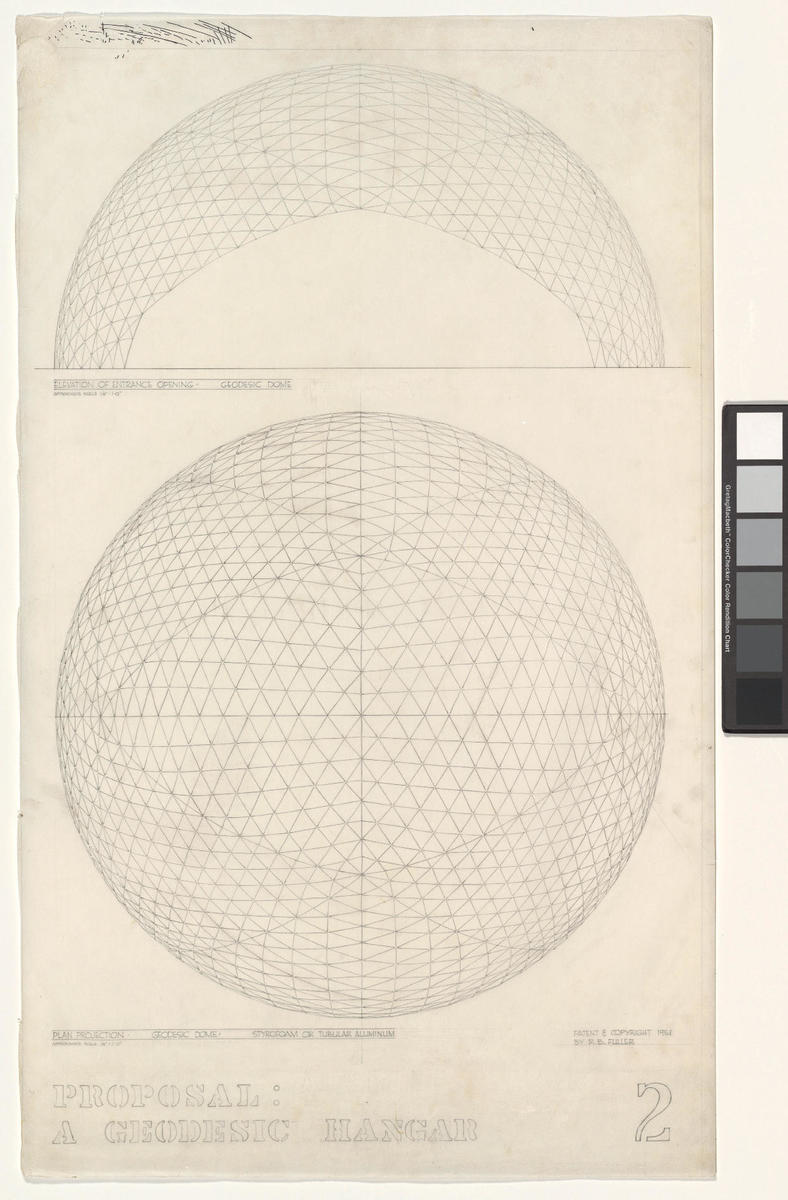

Taking its name from the Enki Bilal film Bunker Palace Hotel (1989), this exhibition offers to re-contextualize the late artist Huseyin Alptekin’s fascination with bunkers, marking the extension of an ongoing project for which Alptekin had dislocated a bunker from the soil of the Albanian coast, exhibiting it in museums in Albania and Germany, with the intention of eventually bringing it to Istanbul. The bunker will be presented in the vicinity of the Yapi Kredi art gallery, while inside, a collection of work and imagery related to the Bunker Research Group — a research project producing documentary material about Albanian military bunkers — will frame the project. The initiative stems from discussions on mobility and peripheral geographies between local artists and artists in transit at a nonprofit space run by artists in Istanbul, the Sea Elephant Travel Agency. Here, the juxtaposition of the words “Bunker,” “Palas,” and “Hotel” seem to evoke metaphors of insecurity, power, borders, paranoia, and the line separating hostility and hospitality.

Cairo

PhotoCairo4: The Long Shortcut

Various venues

December 17, 2008–January 14, 2009

An international multidisciplinary visual arts project based in downtown Cairo, this fourth iteration of PhotoCairo features a series of exhibitions, screenings, presentations, and residencies, as well as a workshop. PhotoCairo4 revolves around a number of loose coordinates, including the city of Cairo itself as a rapidly evolving space in which the tensions between the formal (manifested as state-mandated narratives, media, etc.) and the increasingly informal create unexpected surprises. How, the exhibition asks, do people craft novel strategies to survive in such a space, and how does the city — this or any city — evoke the poetry embedded in daily life?

Artists presented will include Ala’ Younis, Ahmed Kamel, Artur Zmijewski, Babak Afrassiabi, Bernard Guillot, David Thorne, Julia Meltzer, Doa Aly, Hala Elkoussy, Hassan Khan, Heidrun Holzfeind, Ihab Jadallah, Kareem Lotfy, Larissa Sansour, Leopold Kessler, Maha Maamoun, Mahmoud Khaled, Mandy Gehrt, Mohamed Allam, Raed Yassin, and Rana El Nemr. Publications, presentations, and film programs will involve the likes of Bassam El Baroni, Ganzeer, George Azmy, Florian Wüst, Karim Tartoussieh, Martí Peran, Nat Muller, Pages magazine, Urs Lehni, and What, How & For Whom curatorial collective. The Long Shortcut is curated by Aleya Hamza and Edit Molnar of the Cairo-based Contemporary Image Collective.

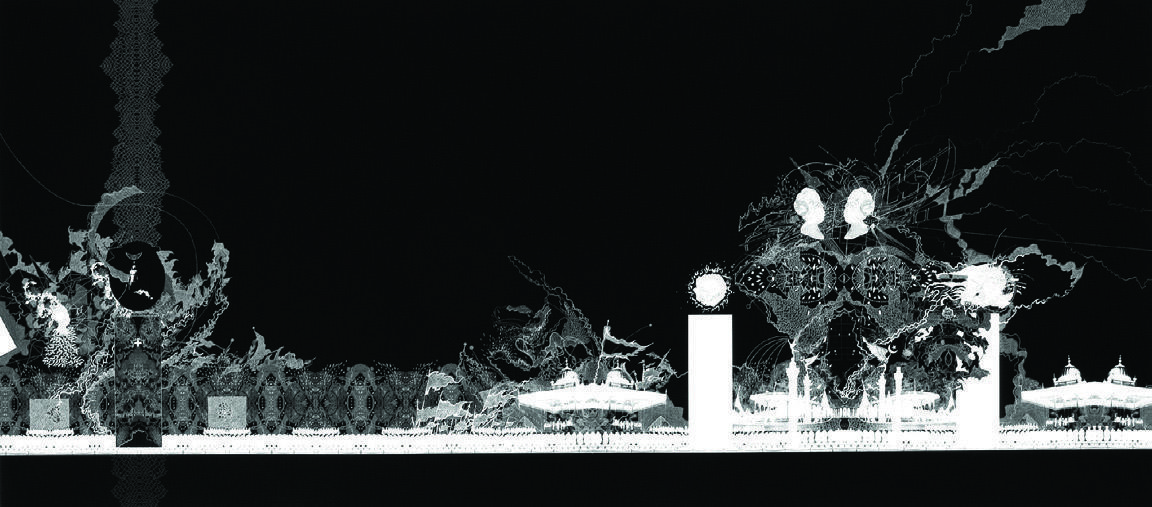

London

Past Potential Futures

Part I: Gasworks

February 14–April 5, 2009

Part II: The Showroom

May 2–June 28, 2009

Gasworks and The Showroom present a two-part exhibition titled Past Potential Futures, the first solo presentation of the Otolith Group’s work in London. The Otolith Group, comprised of Anjalika Sagar and Kodwo Eshun, produces work that engages issues of identity and nation from an unusually radical perspective. Past Potential Futures will begin at Gasworks with the artists’ films Otolith (2003) and Otolith II (2007), both of which envisage twisted futures that, somehow, shed light on the present (Otolith predicts a future in which the human race can no longer survive on earth and must live in zero-gravity space stations, and Otolith II engages the past via a feminist archive from India, of all things).

The second part of the exhibition will take place at The Showroom and feature the third installment in the trilogy: Otolith III. The point of departure for Otolith III is The Alien, an unrealized film by legendary Bengali director Satyajit Ray. Written in 1967, The Alien would have been the first science fiction screenplay to be set in contemporary India. Otolith III returns to 1967 and gives Ray’s Alien an alternative trajectory by which one of the protagonists, the industrialist, decides to go ahead and make the film rather than confront Ray about his failure to make it happen. Filmed on location in London, Otolith III is a temporally and geographically displaced pre-make — a remake of a film that hasn’t yet been made.

A series of public programs as well as a book published by Sternberg Press, will accompany this large-scale event.

Sharjah

Sharjah Biennial 9: Provisions for the Future

March 16–May 16, 2009

After its 2007 edition, the Sharjah Biennial refocused its energies on acting as a year-round “laboratory,” providing grants and production opportunities to artists to create site-specific work and other projects, and furthering its emphasis on practice and experimentation — something that could be seen as particularly timely, given the fixation elsewhere in the Gulf on “finished products” and their performance in the marketplace. In its ninth edition, the Biennial exhibition has the (loose) title of “Provisions for the Future” (co-curated by Isabel Carlos, former founder-director of Lisbon’s Instituto de Arte Contemporanea, with long-term Biennial director Jack Persekian). The exhibition will include fifty-seven artists, most of whom answered an open call for submissions and are making new work for the occasion. Running alongside will be the March Meeting, an annual get-together of Arab arts organizations, and a performance program curated by Tarek Abou El Fotouh. This year, the Biennial has been pushed up a month to coincide with neighboring fair Art Dubai; with Doha’s Museum of Islamic Art as part of the package, international visitors will be bound for a whole Gulf tour.

Dubai

Art Dubai

Various venues

March 18–21, 2009

In its third year, Art Dubai is settling down with a heavyweight list of galleries — London’s White Cube, back in for another try after missing 2008, is joined by Paris’s Galerie Emmanuel Perrotin, Lombard-Freid Projects, Max Protetch, and Salon 94, New York. Regional galleries include Damascus/Dubai behemoth Ayyam, The Third Line, B21, and Elementa from Dubai, and Galerie Sfeir-Semler and Agial from Beirut.

The Abraaj Capital Art Prize, launched at last year’s fair and — typical for Dubai — billed as the “world’s most valuable art prize,” marries artists from the region with international curators. At the fair the three winning curator-artist teams will unveil the new works they’ve made for the private equity firm’s corporate collection: Cristiana Perrella is working on a new video with Turkish artist Kutlug Ataman; Carol Solomon is curating Zoulikha Bouabdellah’s floor installation, inspired by Arab contributions to astronomy; and Leyla Fakhr is working with Tehran-based artist Nazgol Ansarinia on a carpet-based work, with the assistance of weavers in Tabriz, Iran. The fair also continues with its popular discussion program, the Global Art Forum.

Dubai

Bita Fayyazi

B21 Gallery

March 15–April 2, 2009

Tehran-based installation artist Bita Fayyazi returns to Dubai in March with a show of around fifty new sculptures, a collection of meter-high ceramic figures. Representing a cross-section of Tehran society, from picnicking families on motorbikes to bodybuilders with kids in tow, this series represents a departure from Fayyazi’s past work. The artist, who has been a staple of Tehran’s experimental art scene, became internationally known for her collections of outsize cockroaches, dead dogs, and other pests. Here, she turns her gaze to the pluralistic nature of Iranian society.

Dubai / Karachi / London

Lines of Control

Dubai: The Third Line

January 14, 2009

Karachi: VM Gallery and Gandhara-art Space

January 28, 2009

London: Green Cardamom

February 18, 2009

London’s Green Cardamom and Dubai’s The Third Line begin a long-term curatorial collaboration with Lines of Control a set of interdisciplinary group exhibitions, in January 2009. South Asia– and Middle East–based artists including Seher Shah, Amar Kanwar, Rashid Rana, Iftikar Dadi and Nalini Malani, and video and installation artist (and Bidoun contributor) Naeem Mohaiemen — will investigate the impact of the India–Pakistan border, and the role of borders in shaping everyday lives in general. Shows in Dubai, London, and Karachi are accompanied by talks, films, and publications.

Doha

Doha series

The Third Line

January–December 2009

The Third Line’s Doha branch launches a new residency program in 2009, selecting four artists from their roster to make a new body of work in response to a trip to the Qatari capital. First is Iranian contemporary calligrapher Golnaz Fathi, who will visit Qatar in January and return in February for an exhibition. She’ll be followed by London-based Moroccan photographer Hassan Hajjaj (April–May), Canadian-Libyan multimedia artist Arwa Abouon (September–October), and Egyptian multimedia practitioner Huda Lutfi (November–December).

Dubai

Alireza Massoumi

Carbon 12

January 15–February 15, 2009

Dubai’s relentless schedule of new gallery openings continues into 2009 with Carbon 12 launching as one of the first galleries in the Dubai Marina development; it kicks off 2009 with an exhibition of new work by Iranian painter Alireza Masoumi. Other artists in the gallery’s somewhat eclectic mix of European and Middle Eastern artists include Markus Oehlen, Thierry Feuz, Tor-Magnus Lundeby, and Katherine Bernhardt. Meanwhile, the Dubai International Financial Center (DIFC) is fast becoming a gallery center to rival Al Quoz, albeit with slick and vast white cubes to match the corporate setting. Recent arrivals include the Al Shroogi family’s impressive Cuadro Gallery; another branch of the international commercial joint Opera Gallery; and established Middle Eastern dealership Artspace, making the move from its old home at the Fairmont Hotel. Specialist photography gallery The Empty Quarter, directed by curator Elie Domit and backed by renowned Saudi photographer Reem Al Faisal, is set to open in early 2009 and should combine commercial and curatorial savvy.

Tehran / Amsterdam

Sideways in Tehran

Azad Gallery

October 24–November 5, 2008

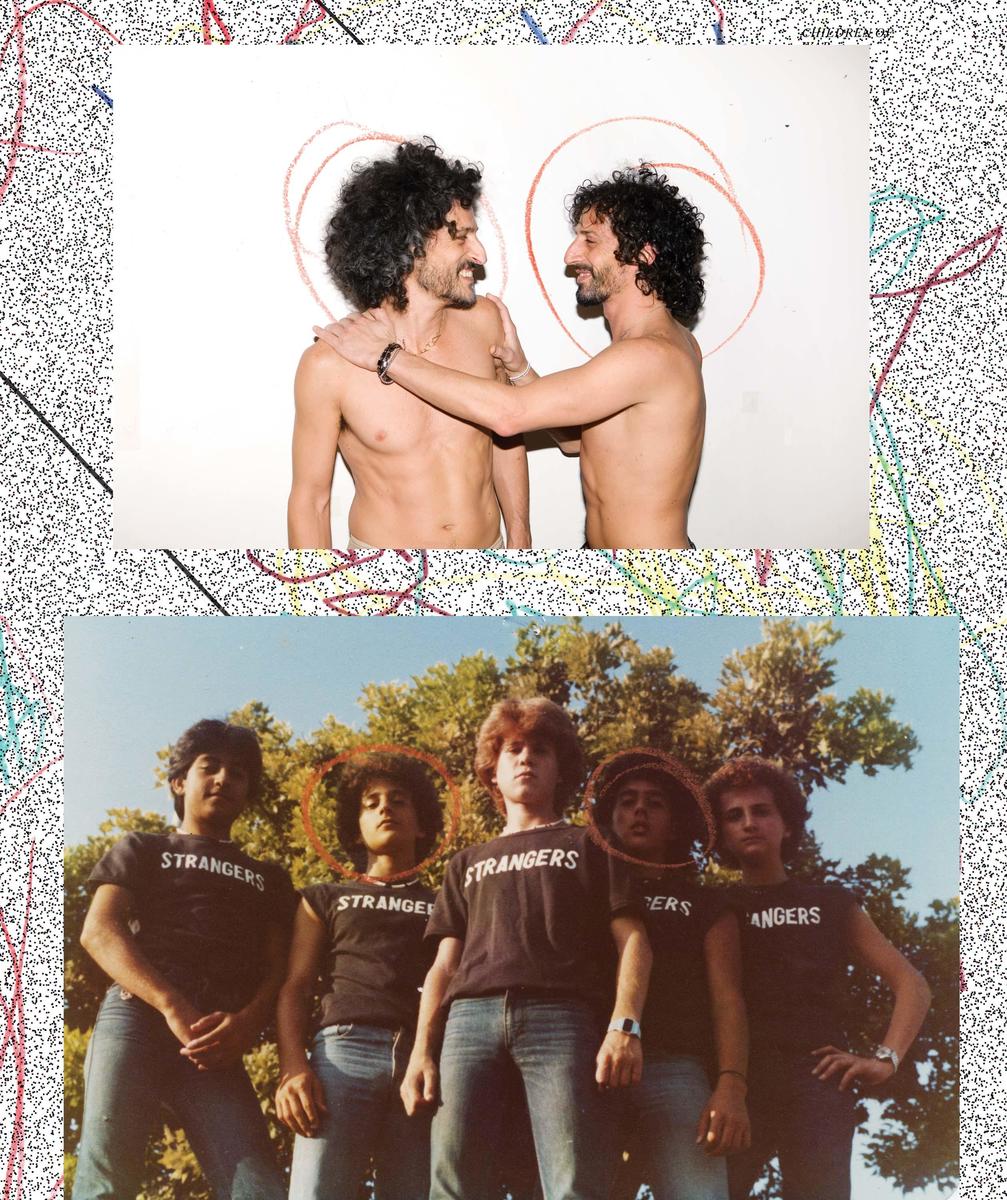

How does a shift in the context surrounding a piece of art influence its reading? How do we judge art that hails from other cultures? Is quality ever universal in nature? These difficult questions make for the starting point of the project Sideways in Tehran, initiated by Tehran-based artist and curator Amirali Ghasemi and Amsterdam-based visual artist Atousa Bandeh Ghiasabadi. The two have asked five artists and writers to produce work that will be presented in both Tehran and Holland — hence raising the aforementioned questions about context, framing, and reception. Among the works in progress are Katrin Korfmann’s rumination on Berlin’s iconic Checkpoint Charlie as a surreal site for engaging the histories of the Cold War; Tina Rahimy’s thoughts on refuge, memoir, and language; and experimental short films by Syrian artist Bassam Chekhes. Artist Sara Blokland, who is at work on the place of the exotic in photography, and Nickel van Duijvenboden, who takes his past life in a punk band as the point of departure for short fiction, round out the participating team. A final project book and exhibition is planned for debut in Holland in 2009.

London

Unveiled

The Saatchi Gallery

February 5–May 6, 2009

London’s Saatchi Gallery assembles an impressive roster of artists for their first major foray into the Middle Eastern art market in the provocatively titled Unveiled. Among the artists in this sprawling group show are Rokni Haerizadeh, whose work references traditions of Iranian portraiture (though always in slightly irreverent fashion — his elongated figures look a bit like Oriental ballerinas en route to a ball). Likewise, Ramin Haerizadeh (Rokni’s brother) teases convention in digitally manipulated photographic works, turning codes of portraiture — and of gender — on their head. Other works include Amsterdam-based Tala Madani’s luscious tableaux; Laleh Khorramian’s fantastic landscapes, which are as much ruminations on painting as they are mini-epics; and Ahmed Alsoudani’s impressively chaotic Guernica-like drawings treating the psychology of violence.

London

Tate Triennial 2009: Altermodern

Tate Modern

February 3–April 26, 2009

The fourth Tate Triennial opens this February with the intention to navigate what it means to be modern today. Curator Nicolas Bourriaud has coined the term “altermodern” to describe art that belongs to the so-called global era but is also a response to the mind-numbing standardization and commercialism around us. Such art, he offers, tends to be characterized by artists’ cross-border, cross-cultural negotiations; the negotiation of different disciplines; the use of fiction as an expression of autonomy; and a concern with the celebration of difference and singularity. The exhibition, plainly ambitious in nature, will map out this brave new altermodern culturescape, presenting new and commissioned works by artists living in the UK, British artists living abroad, and passersby. A series of “Prologues,” four one-day events, are taking place in the lead-up to the show, to provoke debate around the triennial’s themes, with contributions from writers, art historians, artists, and philosophers, including Tom McCarthy, Jordi Vidal, TJ Demos, Carsten Höller, Okwui Enwezor, and Ultrared.

Cairo

Cairo Biennale 11

Various venues

December 20, 2008–February 20, 2009

This year’s Cairo Biennale takes the unwieldy but well-trodden theme of “The Other” as its point of departure. Initiated and run by the country’s Ministry of Culture, the Biennale is typically a chaotic compendium of the very good and the very mediocre. This year, the ministry has commissioned Ehab Ellaban to serve as curator, overseeing eighty-eight artists from forty-four countries. To his credit, Ellaban seems to be straying from the event’s traditionally safer curatorial tendencies, including more video, installation, and performance than we’ve seen in years prior. Among his noteworthy commissions is Cairo-based artist Lara Baladi’s Borg El Amal (Tower of Hope). Housed in a constructed seven-meter Babel-esque brick-and-cement tower that seems to evoke the temporary settlements that dot the Egyptian landscape, the artist’s installation will also host an opera whose primary protagonists are melancholic donkeys. Part operatic soap, part sculpture, the work proposes to subtly address the human dramas that are both typically Egyptian and universal in nature. The other Egyptian representatives include painter Adel El Siwi, Essam Maarouf, Hanafy Mahmoud, Wael Darwish, and Arman Agoub. Also to look out for are Kader Attia representing Algeria; Waheeda Malullah showing for Bahrain; and Sabhan Adam and Buthayna Ali standing in for Syria. The Biennale will take place at its usual venues: the Gezira Art Center, the Mahmoud Khalil Museum, and the Cairo Opera House, plus a new temporary gallery near the opera house dubbed “The Space.”

New York

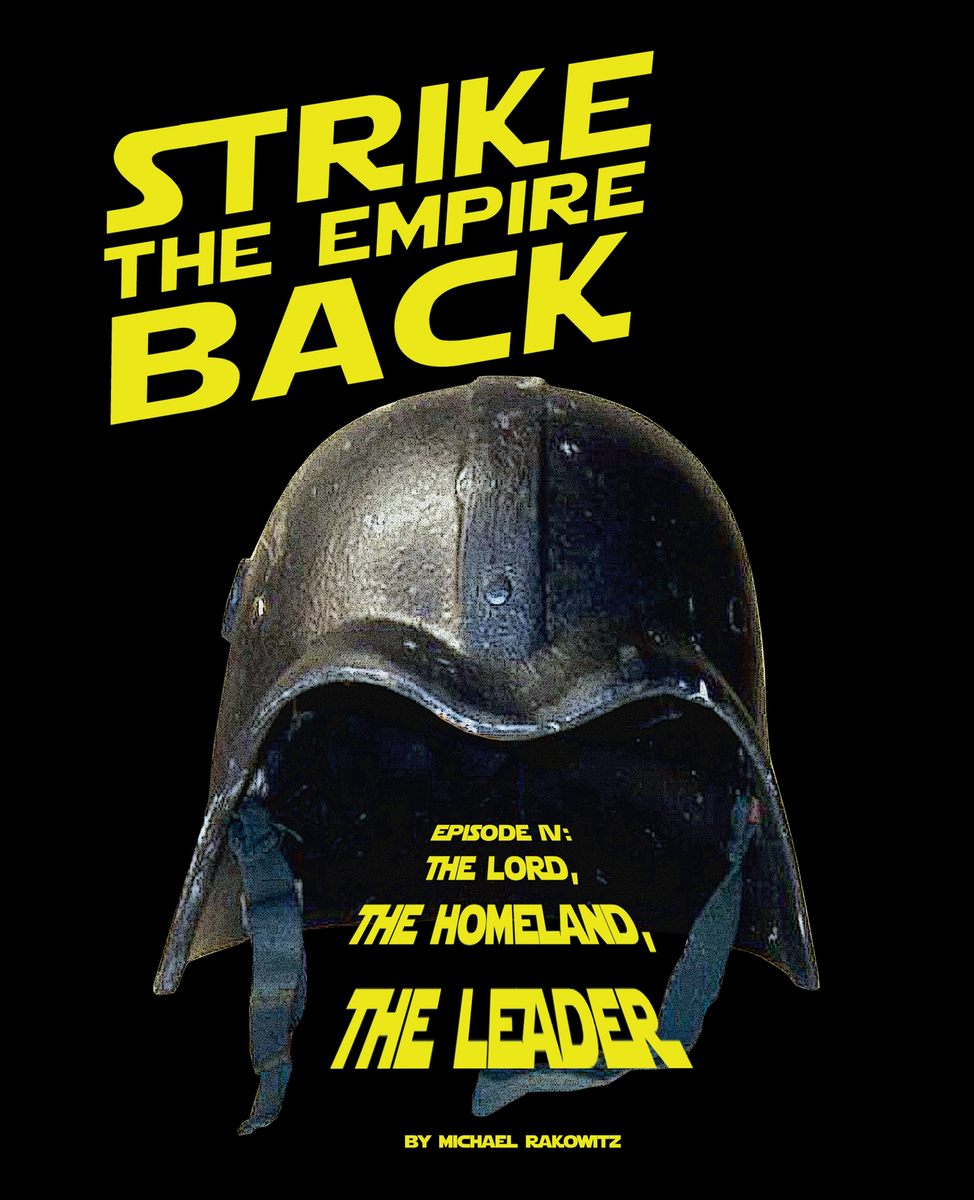

Michael Rakowitz: The Worst Condition Is For a Person to Pass Under a Sword That Is Not His Own

Lombard-Freid Projects

March 3–April 4, 2009

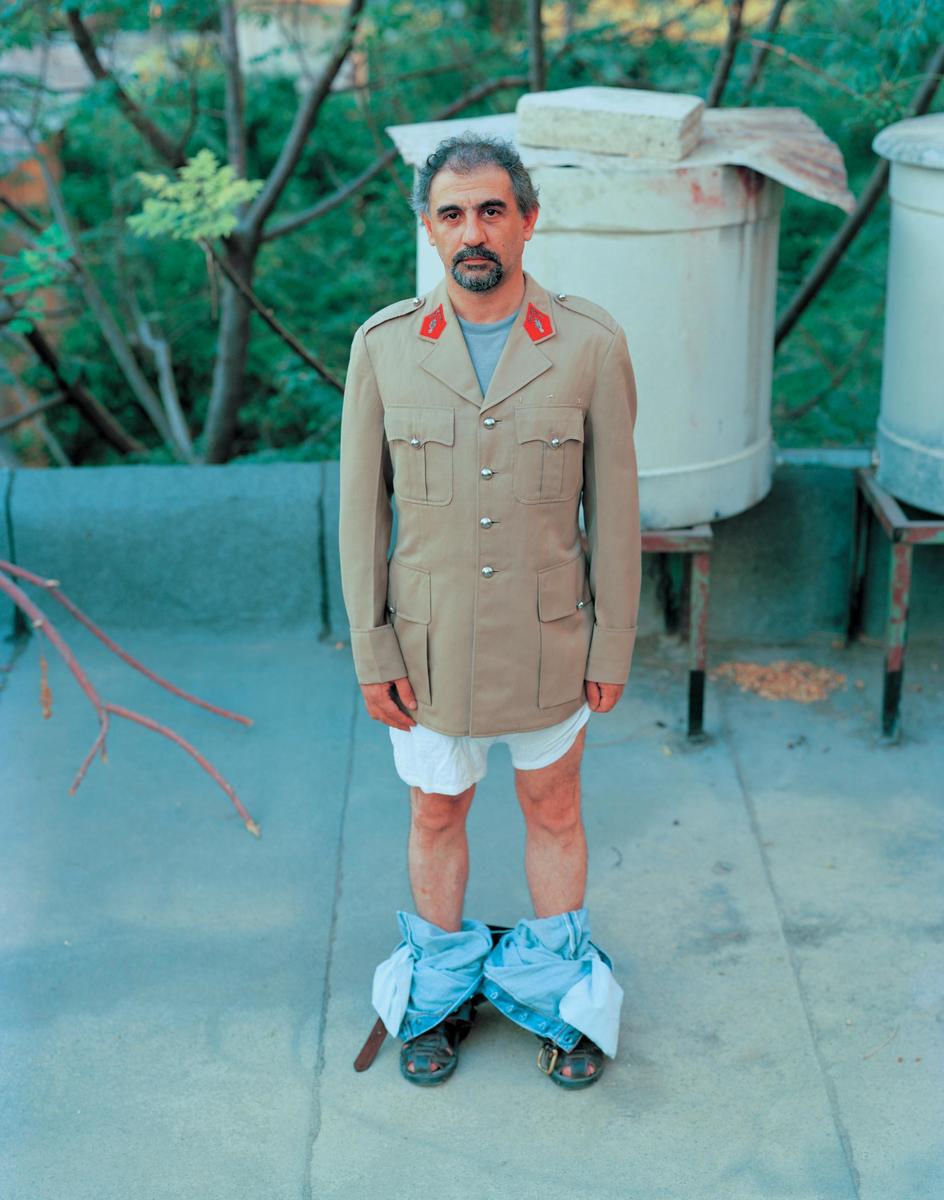

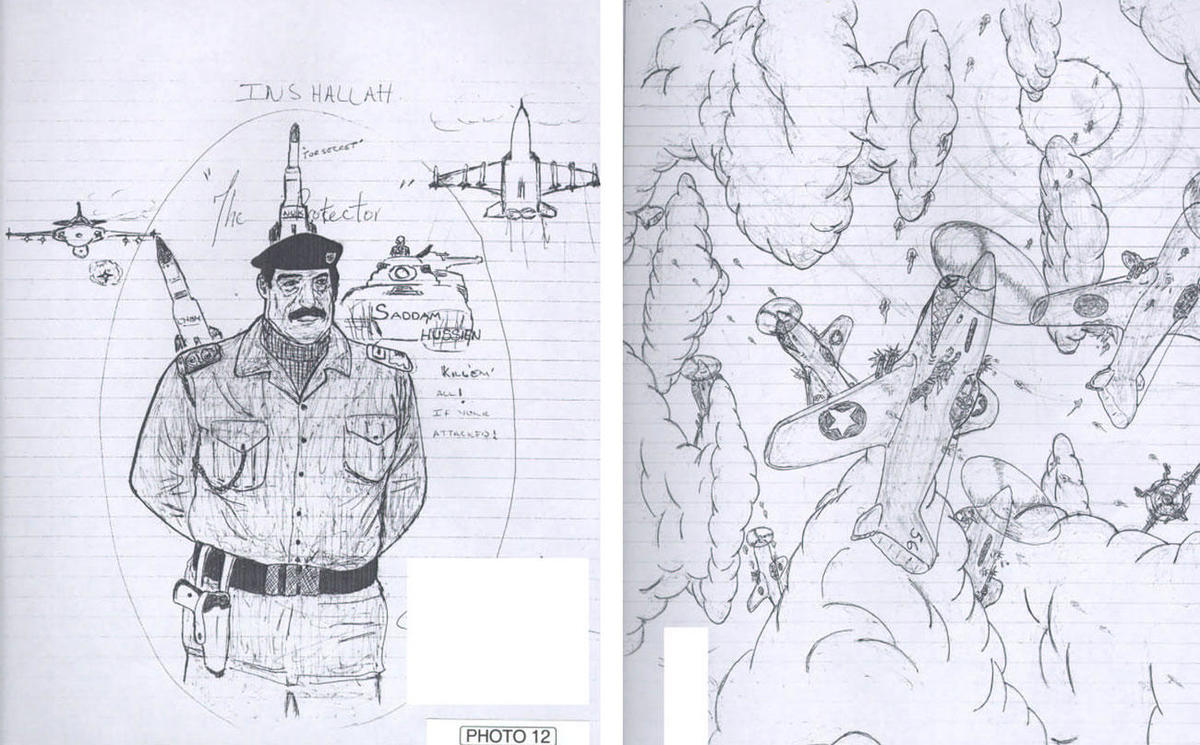

Michael Rakowitz presents his latest musings on history and its discontents with the excellently titled The Worst Condition Is For a Person to Pass Under a Sword That Is Not His Own. In a sculptural installation supplemented by his trademark drawings, Rakowitz will navigate the mimicry of science fiction and cinema in Saddam-era monuments, Iraqi military uniform design, and the larger resonance of these things in the Gulf over the past thirty years. Ostensibly both an extension of and departure from The Invisible Enemy Does Not Exist — his painfully detailed recreation of archeological artifacts looted from the National Museum of Iraq in the aftermath of the American invasion of April 2003 — his latest work stands to make us think again about how the most peculiar accidents of history may intersect with the grand narratives of our times.

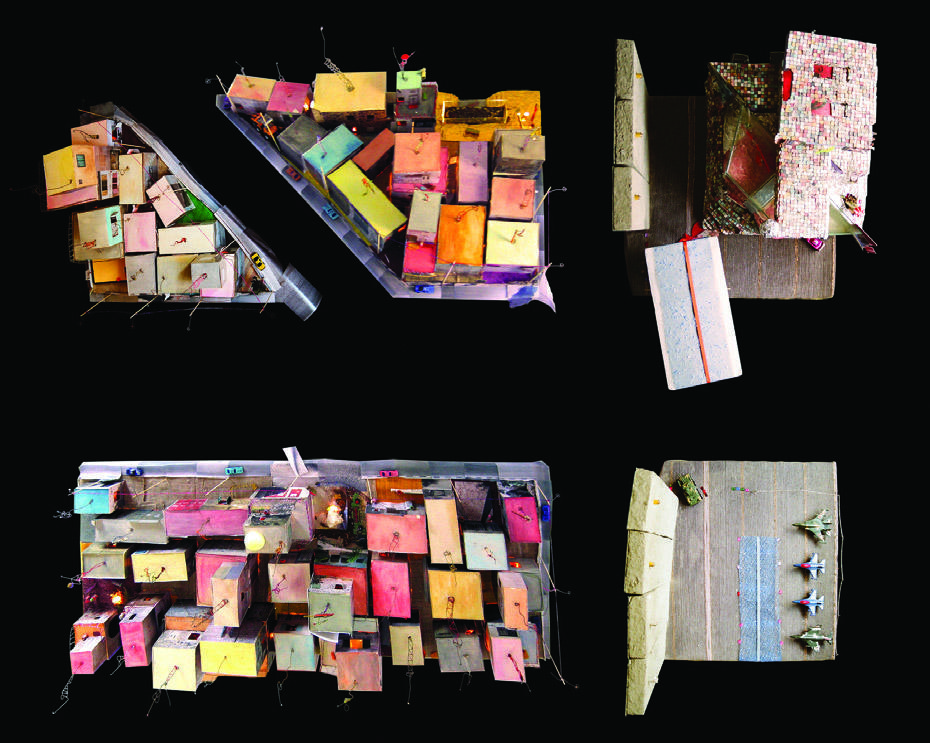

Cairo

Townhouse Neighborhood 1:35

Townhouse Gallery

March 14–April 8, 2009

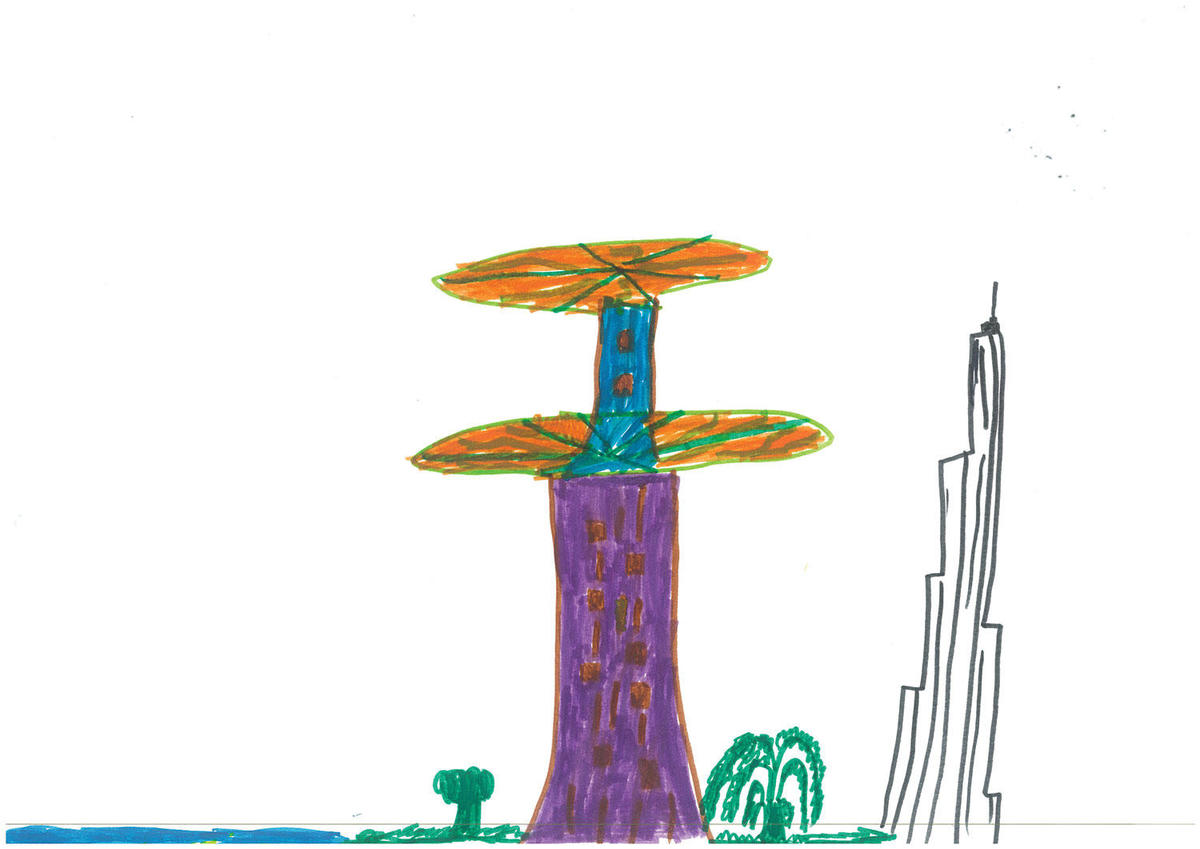

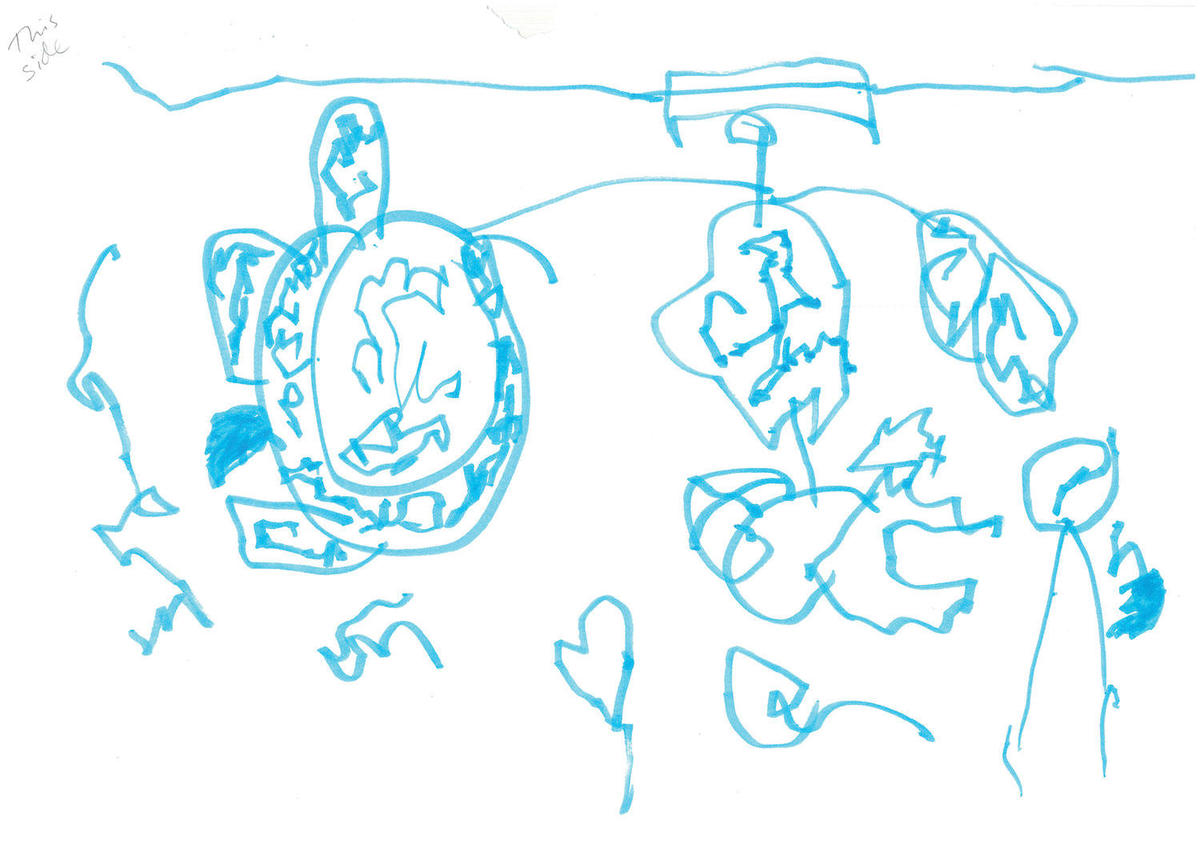

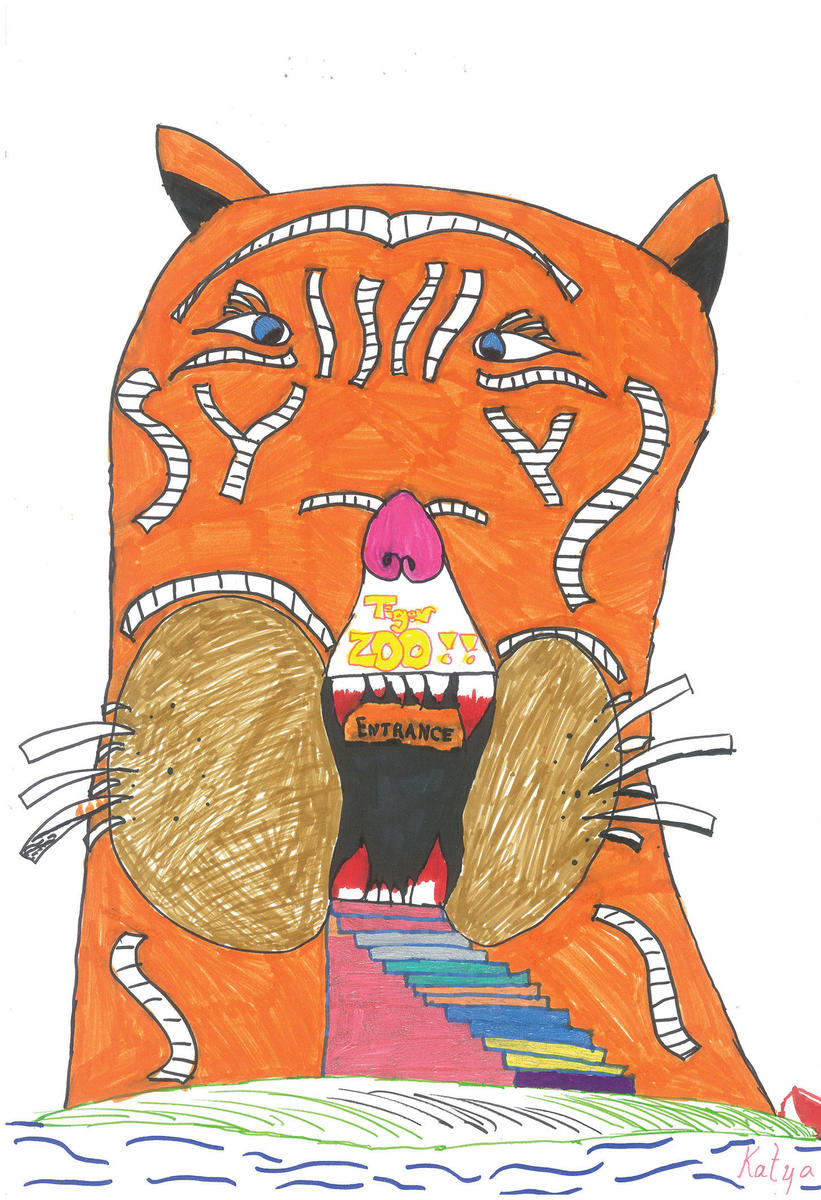

The basis of the Townhouse Neighborhood 1:35 project is a small-scale model of the Antikhana neighborhood, a former bohemian stomping ground that surrounds the Townhouse Gallery in downtown Cairo. Using the maquette as its inspiration, this long-term initiative hopes to unravel the complexity of the urban fabric in this peculiar location, particularly as it faces massive pressures born of gentrification. In this three-part project, persons from the neighborhood itself will take part in a series of workshops, reflecting on their surroundings and thinking about how they could be improved. The maquette, in turn, will evolve from a realistic representation toward a utopian visualization. In the meantime, a group of architects and urban planners are in the midst of developing a plan to transform the abandoned Said Halim Pasha Palace — an epic, crumbling ode to turn-of-the-century monumentalism located across from the gallery — into a museum of Cairo. Finally, the results of the workshop will be presented in an exhibition in the spring.

London

Infrastructures and Ideas: Contemporary Art in the Middle East

Tate Britain and Tate Modern

January 22–23, 2009

The world’s most popular museum turns its attention to the Middle East in January, with a two-day symposium that will explore ideas from the changing definitions of the region and its art to writing, translation, exhibitions, and that old chestnut, “tradition and modernity.” Other sessions will assess the impact of grand museum plans, such as those for Abu Dhabi’s Saadiyat Island, on more flexible commissioning organizations, such as Ashkal Alwan and the Sharjah Biennial. The symposium, organized by Tate staff with independent curator Gilane Tawadros, can be seen as a prelude to the museum’s engagement with the region, in terms of future exhibitions, research, and acquisitions. Speakers will include the usual suspects — Platform Garanti Contemporary Art Center director Vasif Kortun, Bidoun’s Negar Azimi and contributor Shumon Basar, Townhouse Gallery’s William Wells plus a good sprinkling of artists: Wael Shawky, Michael Rakowitz, Yto Barrada, Anas Al-Shaikh, and Hassan Sharif, among others.

London

YZ Kami: Endless Prayers

Parasol Unit Foundation for Contemporary Art

November 21, 2008–February 11, 2009

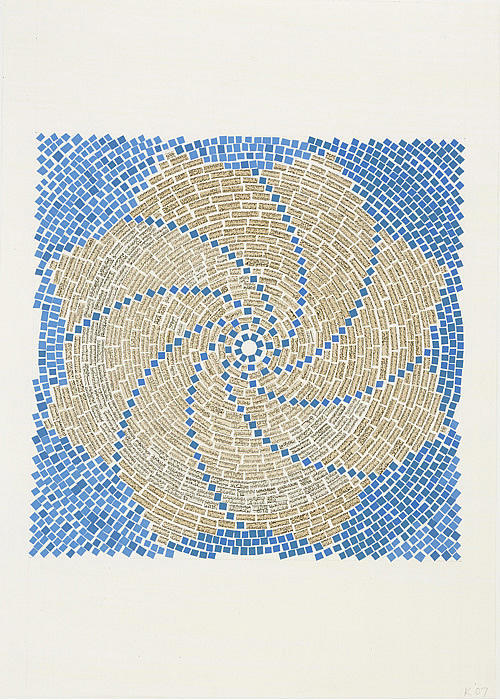

London-based Parasol presents ten years worth of paintings and works on paper by New York-based artist YZ Kami. Among the works showing are a series of the artist’s large-scale photorealist portraits. All of these portraits, some as large as two by three meters in size, capture their subjects in a moment of reflection, of pause, of distraction. They are remarkable in their ordinariness, their resistance to being precious or photographic in that decisive-moment sort of way. The same frontal emphasis and detachment are present in his monumental photographs of Islamic sites and architecture, some of which will be shown here. Also included are works on paper that often take Sufism as their point of departure, subtly and evocatively blurring the lines between physicality and essence.

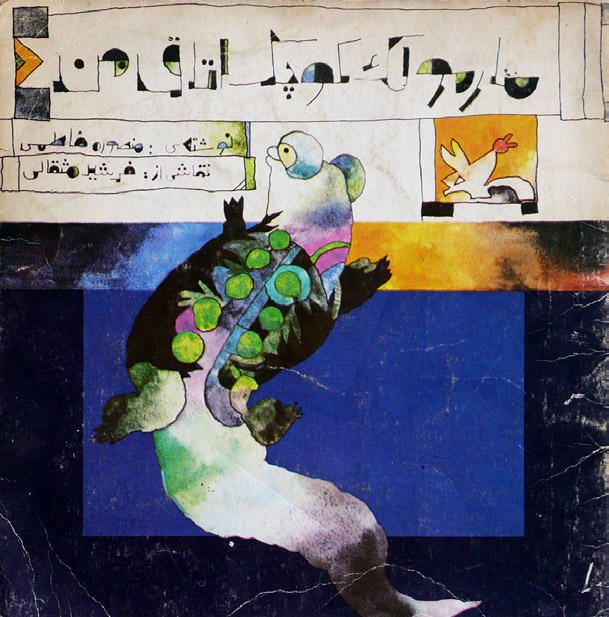

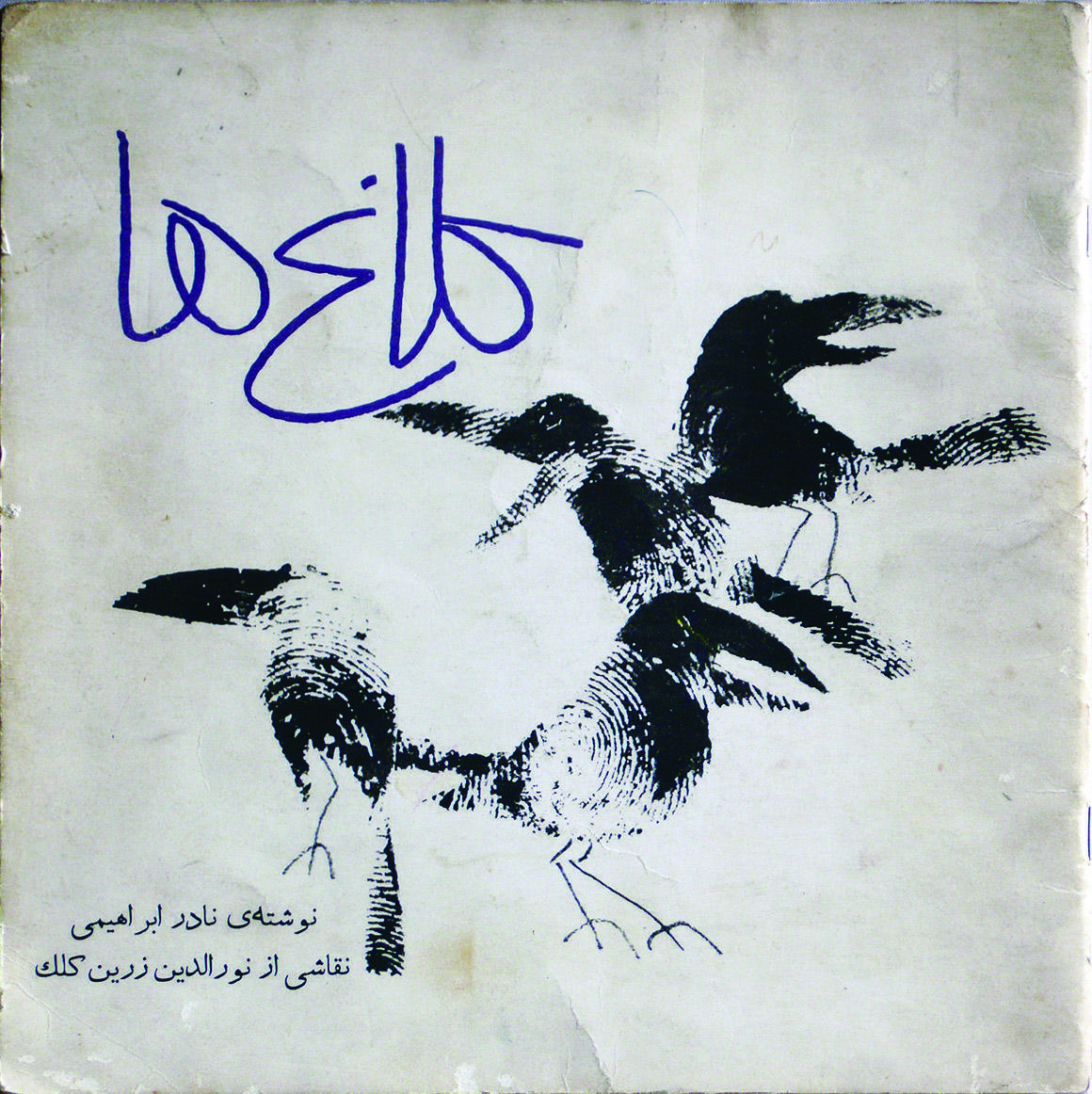

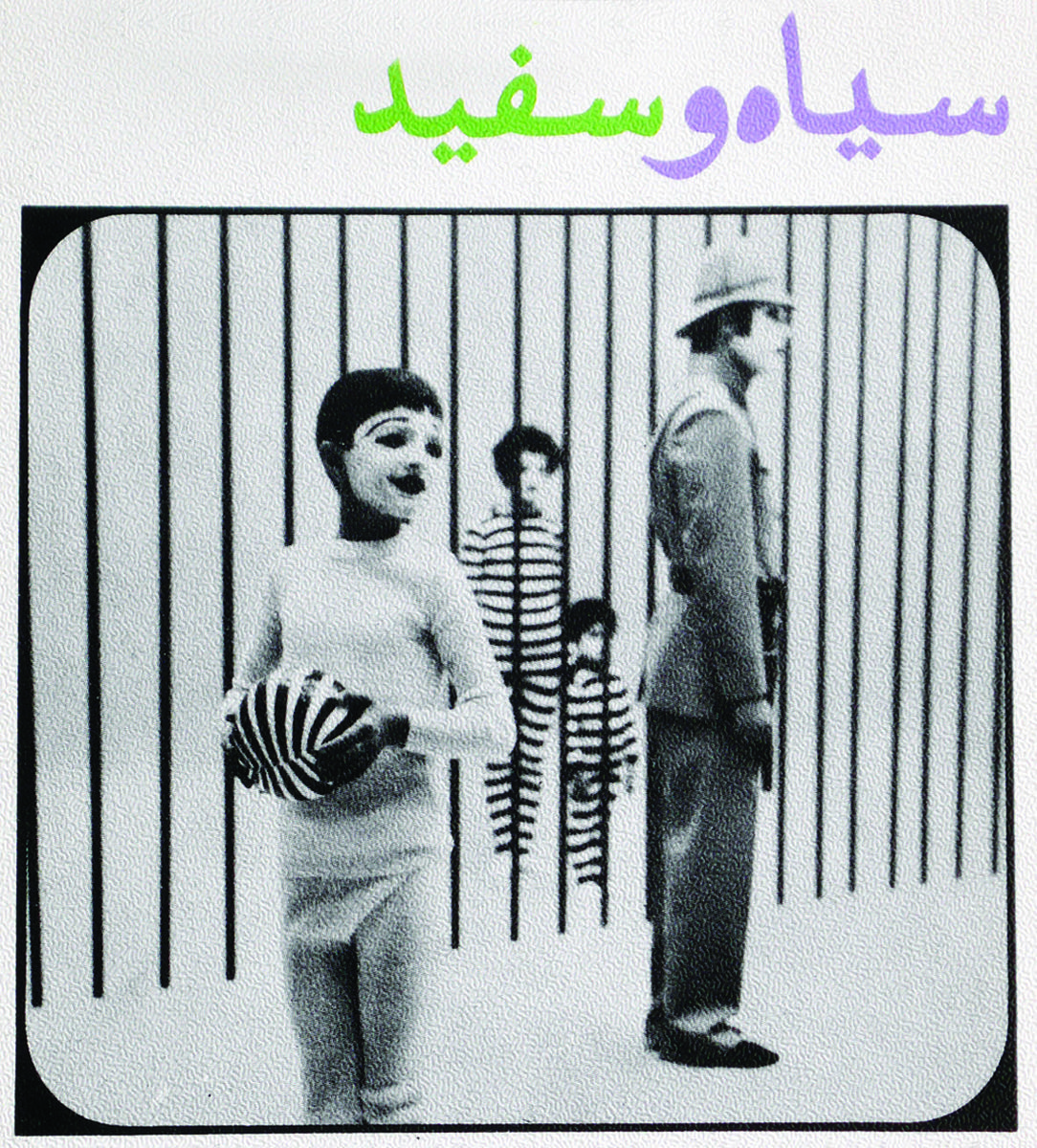

Before there was an Iranian New Wave, there was Kanoon. Founded in 1965 with the blessing of then-queen Farah Diba, the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults — mostly referred to as Kanoon, an abbreviation of the Farsi name — produced books, audiotapes, and films, both animated and live action, for Iranian children from Tehran to Bushehr, Sistan, and Baluchistan. Stories such as Baba Barfi (Father Snow), Amoo Norooz (Uncle New Year), The Journey of Sinbad, or Khorshid Khanoom Aftab Kan (Shine on, Lady Sun) were tales that all Iranian children would come to know and cherish. Prior to Kanoon’s founding, most children’s books in the country were translations of Western classics. There was Pinocchio, The Little Prince, and Tin Tin — all in slightly clumsy Farsi.

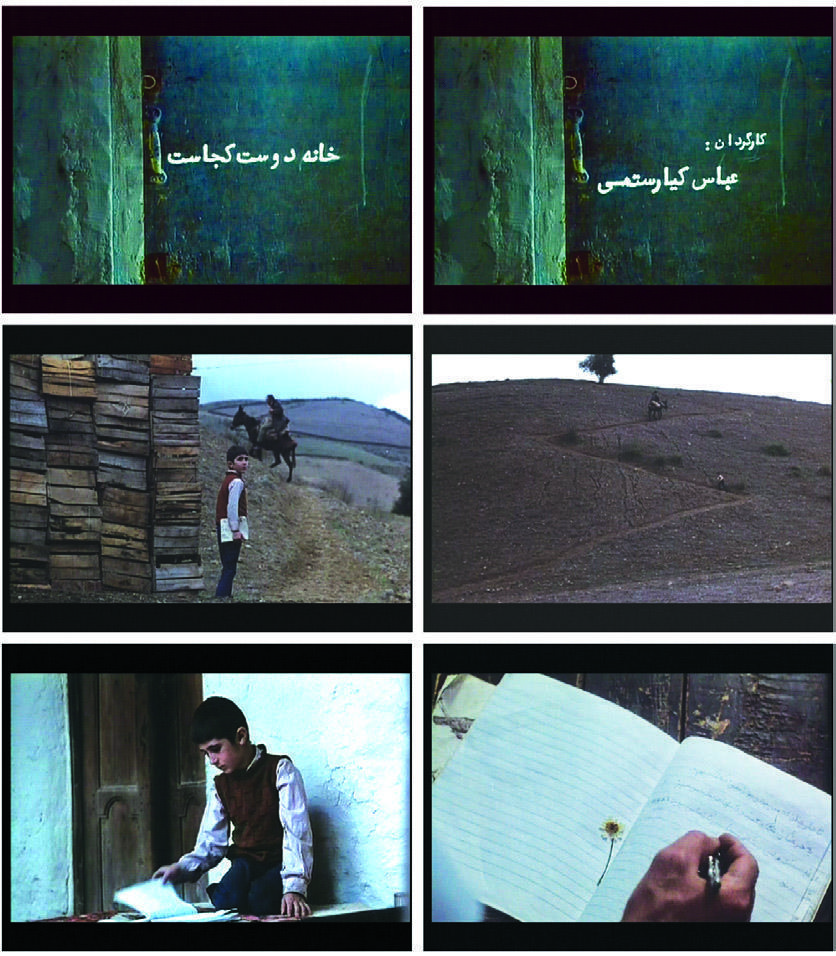

The history of Kanoon is equally entwined with many of Iran’s most epic late twentieth-century stories, from Empress Farah’s cultural initiatives to the heyday of the Iranian left to the revolution. Kanoon would become a sort of incubator for some of the country’s most celebrated artists — including Ebrahim Forouzesh, Noureddin Zarrinkelk, and many of the protagonists of Iranian cinema, Sohrab Shahid-Sales, Abbas Kiarostami, and Amir Naderi among them.

The following is the first in a series of conversations in Bidoun about Kanoon. Here, Arash Sadeghi engages his father, the painter Ali Akbar Sadeghi, who is best known for pioneering a style that mixed traditional Persian coffeehouse painting and the surreal, and Farshid Mesghali, one of Kanoon’s most important graphic designers and animators. Among the elder Sadeghi’s most iconic projects during his time at Kanoon was Malek ol-Khorshid (King of the Sun, 1975), a magical animation inspired by the tenth-century Persian epic The Shahnameh (The Book of Kings). Mesghali is probably most beloved for his illustration work on the book Mahee Siya Koochooloo (The Little Black Fish, 1968). Here, the three discuss the founding of Kanoon and its activities up until the time of the revolution of 1979. One way to gauge a nation’s history, after all, is to look at what its children have been reading.

Arash Sadeghi: Can you tell me a little about how you entered Kanoon?

Ali Akbar Sadeghi: After all these years and at this old age, I can’t remember too many details. But I can say that two great people, Lili Amir-Arjomand and Firooz Shirvanloo, created a factory called Kanoon whose goal was to support creativity among the next generation of Iranians.

Now, how did I become a Kanooni? One day, Abbas [Kiarostami] told me that Kanoon was to publish a book and needed someone who could illustrate the text in classical Persian style. He asked me to come to their offices and, like that, with the book Pahlavan-e Pahlavanan (The Champion of Champions), my relationship with the institute began. I have the best memories of my life from my time there.

AS: Mr Mesghali, can you tell me about the birth of Kanoon?

Farshid Mesghali: I’m really excited. After all these years, someone is asking me to recount the story of the birth of a revolution. Let’s start.

Farah Diba, the last Iranian queen, had a close friend named Lili Amir-Arjomand. They had been roommates while they were students in France. When Farah became the queen, Lili, who had studied to be a librarian, was appointed head of the national oil company library.

After a short while, in 1965, Lili, with Farah’s support, proposed that a library be built in Laleh Park — it was called Farah Park back then — for children and young adults. This was to be the first specialized library for children in Iran, and they also planned to publish children’s books.

Their first book was The Little Mermaid, complete with Farah’s own illustrations. Many people do not know this and this first book and the establishment of the library were the starting points of Kanoon. In fact, in the beginning, Kanoon’s activities were limited to translating and importing books from abroad.

In 1965, Lili officially launched Kanoon with Farah’s support. She would be the first director, along with a man named Firooz Shirvanloo.

I knew Firooz from many years ago, when I was working at Franklin Publications with Arapik Baghdasarian. Firooz is the most important person in the history of Kanoon, in part because of his political background. Firooz had studied philosophy in England and had come back with leftist tendencies. He was also a member of the Iran-Britain Student Confederation. They were known for their extreme revolutionary ideas.

After returning to Iran from Britain, he was the art director of Payk magazine for young adults, which was published by Franklin Publications. These days you can find the magazine in news kiosks under the name Roshd.

After the confederation became embroiled in a failed attempt to kill the Shah in 1965, Firooz was arrested by one of the Shah’s insiders in the Iran-Britain Student Confederation and sentenced to death. After his arrest, they feared me, too, and I was fired.

Europeans objected to the court sentence, and eventually the Shah forgave them, and the death penalty was reduced to a few years in prison. After winning their freedom, some of them were offered important positions so that they might “rethink” their leftist ideas.

Because of his experience in publishing magazines for children, the palace offered Firooz a position in the newly formed Kanoon. At the same time, Firooz had just founded an advertisement group called Negareh and hired a group of arts and literature students from Tehran University to work with him, including Abbas Kiarostami, Ahmadreza Ahmadi, Nikzad Nojoumi, Farideh Farjam, Arapik Baghdasarian, and myself. Eventually they would all migrate to Kanoon itself. But even after prison, Firooz held on to his leftist ideas, and many of the people he brought into Kanoon with him were leftist writers and researchers.

In 1968, Firooz commissioned me to work on one of Kanoon’s first independent books. With the publication of The Little Black Fish written by Samad Behrangi, we gained a lot of attention. I drew the illustrations for that book, and we won the top award at the Bratislava Children’s Book Fair because of it.

[The Little Black Fish is the story of a black fish who dreams of seeing the big blue sea. He faces many dangers, including a heron, which he kills with a dagger. The narrator of the story, a grandmother to many little fish, explains that the little black fish has disappeared by the end — a little like the martyrs who have died trying to find a better world. It was hard not to find political symbolism in this, along with other stories. Incidentally, its author, Samad Behrangi was an active socialist agitator who translated some of Iran’s most avant-garde poets, like Ahmad Shamlou, Forough Farrokhzad, and Mehdi Akhavan-Sales, into his native Azeri language. He drowned in the Aras River in 1967, and his death is generally blamed on the Pahlavi regime.

Also published around that time was Gol-e Boloo Va Khorshid (The Crystal Flower and the Sun, 1967), by Farideh Farjam, illustrated by Nikzad Nodjoumi. This is the story of a flower that miraculously shoots up amid the ice of the North Pole. For a period of six months, the little flower develops a close relationship to the sun. The sun tells the flower about the world and its people. At the end of six months, when the sun has to migrate, the flower asks to move with him. He gets so close to him that the flower wilts and joins the sun forever. Along with The Little Black Fish, The Crystal Flower was honored at the Bologna Children’s Book Fair.]

FM: In 1969, Firooz moved to Kanoon completely and took his colleagues with him, launching a research department, a publishing department, and, upon Kiarostami’s suggestion, a film and animation department. Firooz directed all three, and in 1970, Kanoon’s first short motion picture Nan-o-Kooche (Bread and Alley), directed by Kiarostami, was produced.

[Shot in black and white, the film tells the story of a little boy walking home with a loaf of bread, who is confronted by a hungry dog. In the end, the two get over their mutual suspicions and become fast friends.]

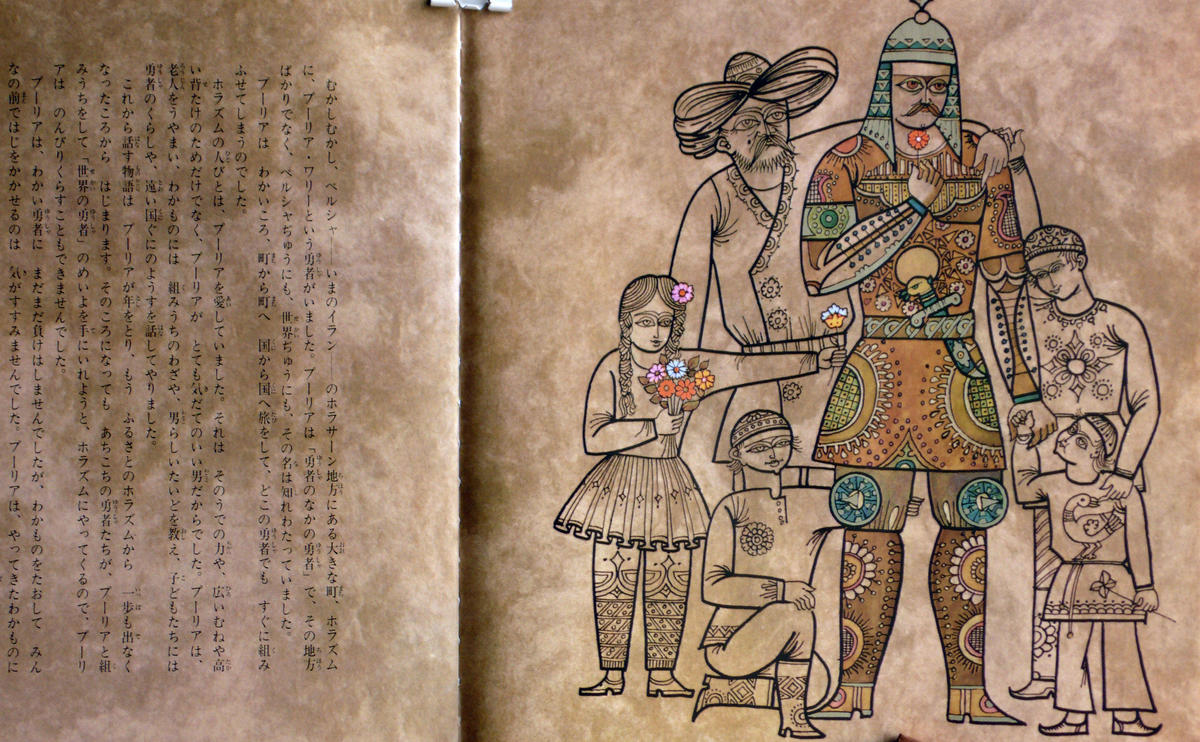

In that same period, the first animations were born, including Agha-ye Hayoola (Mr Monster), created by myself, and Vorood Mamnoo (No Entrance) by Arapik Baghdasarian. With the arrival of Ali Akbar Sadeghi in 1970 and the illustration of Pahlavan-e Pahlavanan by Nader Ebrahimi, and a host of international awards that this book brought for Kanoon, the institution gained more currency and, because of that, more support from the queen.

[Pahlevan-e Pahlevanan is the story of a grand champion named Pooriya-ye-Vali who hears of a younger champion who hopes to triumph over him. The young pahlevan (champion) comes from Sistan to Kharazm to wrestle with Pooriya-ye Vali. His mother accompanies him and prays for him every day prior to the fight. Pooriya hears her, but nevertheless, decides to fight his best fight. He loses to the young champion and leaves his hometown forever.]

Kanoon eventually launched the Tehran Children and Young Adults Film Festival. They were especially interested in Eastern Europe films, like those of Raoul Servais and Jan Oonk. Kanoon hardly let any commercial or empty American films enter the collection.

[Later, that very collection would be the fuel for the post-revolutionary media to broadcast un-American films with educational and cultural values far removed from ostensibly Western or capitalist ideas.]

With the establishment of the film department and the launch of the Tehran festival, Kanoon started to grow rapidly. Many young artists and writers flooded there to make films. Among them were Dariush Mehrjui, Bahram Bezaie, Amir Naderi, Nasser Taghvai, Ali Akbar Sadeghi, Nafiseh Riyahi, Ebrahim Forouzesh, Nader Ebrahimi, Ahmadreza Ahmadi, Cyrus Tahbaz, and even musicians like Majid Entezami, Esmaiel Monfaredzadeh, Hossein Alizadeh, and Sheyda Gharachedaghi. Production increased dramatically.

AS: What year was that?

FM: I’m not sure of the year exactly, but I think it was around 1970, 1971.

Firooz was finally fired from Kanoon at the end of 1972. He had brought one too many leftists to the organization, like Mehdi Samakar and Dr. Rasoul Nafisi, to work as writers and researchers. SAVAK (the Shah’s intelligence services) had always had problems with the leftists, but for the most part Lili had been able to handle them because of her close relations with the palace. But slowly things changed.

When Firooz had to leave Kanoon, the so-called dissident products inspired by leftists were removed. He went on to direct the Niavaran Cultural Centre. But we owe him a great debt for giving us all a start.

AAS: That was our golden age. We won many prizes from all over the world.

[Firooz Shirvanloo would go on to work for Empress Farah Diba’s office, and played a large role in amassing the state’s modern art collection under the patronage of the empress herself. That collection continues to be known as one of the best modern art collections outside of the West, with its Warhols, Hockneys, Pollocks, and beyond. To this day, it inspires a conspiracy theory or two in reference to what became of the works after the revolution of 1979, and that revolution’s insistence on eliminating all traces of Western culture.]

AS: Can you tell me about the libraries Kanoon founded and ran?

FM: Over the course of ten years, Kanoon built 150 libraries in cities and villages throughout Iran. We created mobile libraries to roam to distant villages and distribute books to the country’s nomads. If there were places the buses couldn’t reach, books were sent to children on the back of donkeys and horses. One can say that Kanoon was playing the role of an independent Ministry of Culture.

AS: How did Kanoon raise money and gain support?

FM: From the beginning, a board of trustees was formed and the queen was in charge of it. Its members were from the Ministry of Art and Culture, the Ministry of Education, the national airline (Iran Air), the Interior Ministry, the Oil Ministry, the Pahlavi Foundation, National Radio and Television, as well as nine major national and cultural figures.

Board members supported Kanoon through their affiliated organizations. For instance, Iran Air was obliged to give children Kanoon products as in-flight souvenirs, or the Oil Ministry would give Kanoon products to the children of the employees. Iranian painters painted for children, Iranian sculptors designed toys, the musicians played at events, and filmmakers were dedicated to making children’s works. Back then, Kanoon’s libraries were the best in the Middle East, and maybe even the world.

The libraries were quickly turned into cultural centers and started to attract children with free books, films, and theater. Children were crazy for Kanoon. There were weekly classes of painting, filmmaking, writing, music, theater, languages, and ceramics at Kanoon’s various centers and libraries.

Around three hundred libraries were active. The mobile libraries were also mobile cinemas and showed films for nomad children or children living in distant villages. By 1979, one million children were members of Kanoon. At least eight million children were touched by Kanoon products, and the books they published numbered over fifteen thousand.

We published all kinds of books, from religious tales about Shia imams to stories about ancient Persian heroes to fantasy and modern stories. Kanoon’s productions took account of all the people of Iran, from north to south, east to west, as well as the capital. There really was nothing else like it.

There were openings every week. Entire shows sold out. Artists were touted, promoted, and written about. In the late 1960s, radical politics and radical art found a home in cafes, galleries, and private collections, supported by wealthy patrons and a rising middle class. There was Janine Rubeiz’s dynamic intellectual hangout, Dar el Fan, and Gallery One, founded by Shi’r editor Yusef Khal and his wife, the artist Helen Khal. The Nicolas Sursock Museum held an annual juried Salon d’Automne exhibition of modern art in Lebanon, modeled on the famed French exhibition. A showing at the Salon d’Automne was very possibly the most significant exhibition, in Lebanon, in an artist’s career. Even after 1973 — the beginning of nearly two decades of civil wars — the art scene carried on. Galleries opened and closed and opened again over the years. It was, in an odd sort of way, a special time for the city’s dealers and artists, who continued in spite of the madness around them.

Amal Traboulsi saw it all — a sort of reigning queen of the Beirut art scene, she studied fine art at Beirut’s American University in the Sixties and eventually went from being a collector of young Lebanese artists’ work to owning a gallery herself. She opened La Galerie Épreuve d’Artiste in 1979, in the midst of the civil war, in the Tajer building in the Clemenceau neighborhood of West Beirut. Back then, the area was dotted with boutiques (Danielle Chehab’s Rive Droite was next door). West Beirut was a hub of cultural life. “I just loved the area. It was more open than Achrafieh, and it was the place to be.”

In the beginning, La Galerie Épreuve d’Artiste showed mostly foreign artists — the Chilean kinetic artist Ivan Contreras-Brunet, Belgian artist Lala Akhud, and the German-based Italian artist Bruno Bruni among them. Slowly, Traboulsi shifted her focus to local artists. Collectors including businessman Ramzi Saidi, ministers Ibrahim Najjar and Raymond Audi, and publisher Riyad Rayyes were keen to buy works by Lebanese artists. Painters like Omar Onsi and George Corm, as well as prominent sculptor and painter Aref Al Rayess, were among her top-selling artists. In her four years in the Tajer building, she hosted nearly eighteen exhibitions a year. Almost every one of them sold out, with prices ranging from one hundred to several thousand dollars. (A Chaouki Chamoun painting that sold for a few thousand dollars back then may fetch as much as $50,000 on auction today.)

Even amid the vicissitudes of war, heaps of capital flowed into Lebanon from Arab and non-Arab countries, often courtesy of an arms market that supported the various militias running about this small country. In its own way, the economy was booming, and, as ever, there remained a market for luxury goods, including fine art. “You keep buying art,” says Traboulsi. “The art market never stopped, even when everything around us was blowing up.”

Still, it wasn’t all fun and games. Many afternoons were spent sitting by the radio listening to Sawt Lubnan deliver reports of bombings and advice to Beirutis on which roads they ought to avoid during their daily commute. Traboulsi was living in Achrafieh in East Beirut at the time and crossed into West Beirut daily to reach the gallery. When it was impossible to travel because of road closures, art openings would be postponed.

Few complained.

The end of that era arrived in 1982, with the Israelis. An exhibition of the Jordanian sculptor Mona Saudi was scheduled to open on June 8 — the same day Israeli tanks rolled past the gallery. Traboulsi recalls overhearing three passing Israeli soldiers comment, “An art gallery in Beirut during a war?” She canceled the opening. Two days later, she shuttered the gallery in Clemenceau. There was one more show, an exhibition of Yemeni handicrafts, in April 1983, after which Traboulsi, like most Beirutis, remained bunkered in her part of town.

For the next three years, Traboulsi would hold group shows out of her home in Achrafieh. Perhaps ahead of her time, she urged many artists — Maya Eid, Amin Boulous, Jean Marc Nahas, Névine Mattar, and Nadim Karam among them — to blur the line between design and art. Traboulsi encouraged Ghassan Abu Jawdi, a dentist turned sculptor, to pursue his art, too. (He employed the plaster he used to seal teeth in his work.)

And while conditions were occasionally stark — no fancy invitations, nylon covering the windows when gunfire would shatter the glass — the gatherings-cum-exhibitions were always packed. Nicholas Audi, a now-renowned chef who lived in the building, offered his chocolate truffles to the crowds as Amal played music.

That energy carried into 1987, when Traboulsi converted an abandoned garage into an art gallery, complete with marble floors, in Kaslik, a suburb north of Beirut. She opened the space with popular paintings by Willy Aractingi, who she claims is Lebanon’s first and only naive artist; over the length of his career, he painted each of Jean de la Fontaine’s fables. (Aractingi had also been a “nez,” working as a chemist for Fatale, a Lebanese perfume company designing fragrances.) The energy at openings at the end of the Eighties and throughout the war was “almost hysterical,” she says. People would wait in long lines to see shows. There was music specific to the exhibition at nearly every opening, and on many occasions, there was spontaneous dancing in its midst. At one opening, two years before the end of the wars, Traboulsi set a huge canvas on the floor in the middle of the exhibition space. The artists attending began to paint, and when the paint ran out, they used Nescafé.

Traboulsi held the space in Kaslik until 1997 but was forced to close again due to Christian fighting in the East. She moved to Paris for a few years, where she organized and produced exhibitions on Lebanese art, including 200 Years of Lebanese Art at L’Institut du Monde Arabe. Over the next ten years, Épreuve d’Artiste moved three more times, continuing to move away from the violence with every move, staging shows in nearly ruined spaces like the Maronite Church or the epic “Egg Building” in downtown Beirut. In 1992, Traboulsi sponsored what is commonly referred to as the first installation art in the country, by artist Ziad Abillama — an assortment of sculptural works encircled by barbed wire on a patch of North Beirut beach.

With Prime Minister Rafik Hariri’s rise to power by the late 1990s, there was renewed confidence in the city, and in the art market, too — complete with a rise in prices. A thrice-sold-out Amin al Basha show seemed to confirm this renewed energy.

But all good things must come to an end, and Traboulsi finally closed her gallery doors in 2006. “It’s just not the same as it used to be,” she says about the current moment. Still, she continues to curate shows, sell work, and consult collectors. On the day we met this past fall, our conversation was interrupted by a flurry of calls concerning Christie’s auction results in Dubai that day.

The sudden interest in modern Lebanese and Arab art at large has inspired a surge in exhibitions at home and abroad. Traboulsi ended the conversation reflecting on the various stages of her life’s work, and especially the peripatetic Épreuve d’Artiste. She smiled.“You know, the space had another name. It was called ‘La Galerie qui Bouge.’ It actually was our official name for a while.”

I first heard the Arabic word for “vibrator” by the ice cream machine in a cafeteria at Middlebury College. The rainbow-colored sprinkles that I liked to dump onto my soft-serve swirls had run out, and I was yearning for an attendant who might bring more. Class was going to start again in five minutes, and facing the prospect of three more hours of strenuous grammar, I was fixated on the missing sprinkles. A line started to form behind me. Clare wandered over. Clare was an anthropologist friend from Berkeley who was learning Arabic so that she could “study” nightlife in Beirut. Clare was always late for lunch. I suspected she went back to her dorm after our morning sessions to get high, but I never asked.

Today she looked sad. “My electronic friend is broken,” she said. Sadiiqi al-elektrony la yashtaghal.

“Your what?”

“Sadiiqi al-elektrony,” she repeated. Her eyebrows rose and dropped back down while her head bobbed from side to side. I fidgeted. The queue for ice cream was growing thanks to the kids from the Russian School, and I was nervous I’d be late for class.

“You know, hazzaza,” she bobbed again. “From the verb to shake, convulse, tremble, quiver.”

I stared at her blankly.

She pulled her electronic friend out of her bag, its pinkish silicone tip visible for me to see. One of the teachers brushed past, a tightly veiled Egyptian. “The root of ‘to shake’ is ha, za, za,” the Egyptian whispered, with one eye on Mr. Silicone. Am I imagining things? Did she wink at us? This question occupied us for days.

We were bored. The hazzaza incident, or hadath al-hazzaza, as it came to be known, was a millimoment of fun amid an otherwise very serious nine weeks. When Hans Wehr (his text was our bible, a green Arabic-English dictionary) couldn’t supply the answers, we invented words. Tofurkey, a cafeteria staple — Wikipedia calls it a “portmanteau of tofu and turkey” — we called kharra, or shit. We found occasions to speak of pornography (esteporn), fashion victim (dahiyat al-moda), lesbians (al-butchaat). Electronic friends. We estimated, improvised, reconceived, and mostly butchered the Arabic language out of sheer lassitude. We also developed crushes — on students in other language schools, on our teachers, very rarely on each other. And at times we were mean. Really mean. It was like junior high school all over again.

Middlebury, Vermont, sits 135 miles north of Boston and several hundred miles south of the North Pole. In the winter it’s known for its exceptional bobsledding pistes, and in the summer, its kayaking and competitive “canoe polo.” The town, whose population was a little over 8,000 people at the time of the last census, boasts a handful of notable residents, including John Deere, the creator of the eponymous tractor, and Bobo Sheehan, the coach of the 1956 Olympic alpine ski team. The great American poet Robert Frost also spent more than two decades moping around the woods being depressed here.

And yet outside the greater New England area, Middlebury is mostly known for its incomparable language study. Chinese, French, Hebrew, Portuguese, Spanish. During the Cold War, legions of patriotic polo-shirted Americans came here to learn Russian. Later, when the economies of the Far East were booming, many came to learn Japanese and Chinese. Today, it’s Arabic’s turn. Year after year, hundreds of bushy-tailed (and many Bush-supporting) Orientalists, some more seasoned than others, make their way to this remote location. Here, among the fresh-faced, flip-flopped masses that give this part of the world its discrete charm, students learn the finer points of grammar, elocution, and execution. For those in the know, the pilgrimage to Middlebury is a rite of passage, a… bar mitzvah?… into the rarified world of the Arabic language.

Week One, Day One

It is difficult, having given up undergraduate life some years ago, to accept that to master Arabic one must live in a dorm. We sleep in narrow beds, for which one must buy special sheets. Those of us who refuse to buy special sheets on principle are left to make do with cold, itchy, inhospitable vinyl. Most students have roommates, too. Out of fear of being assigned one, I had every medical doctor in my family pen a note attesting that I am an insomniac, that I have been known to walk in my sleep, that I can be abusive in the night. But the sweet success of being assigned a single is quickly tempered by the room’s size; I call it “Little Gaza.” I tape images of Dalida on my walls.

We take our placement exam today. In the gymnasium-sized cafeteria, minutes before the exam, dozens of students have their heads buried deep in their Arabic books. They are cramming. Others are stuffing bananas and Power Bars into their backpacks as provisions for the hours to come. I force myself to look away but must admit to having pangs of anxiety as we walk toward the testing hall. Where is my Xanax when I need it?

After the exam, H and I decide to go for a swim at the university’s sprawling indoor athletic complex. Though the sky looks grey and ominous as we set out on our school-provided bicycles, we decide to chance it and forego umbrellas. H does laps while I do the sidestroke like my grandmother does it. We shower, and as we prepare to return, we find that the lobby of the athletic complex has been flooded by torrential rain. We turn and run, only to find that we are trapped by water on every side. Finally, a kind man leads us out to his pickup truck and drives us back to the dorm. H has an Arabic dictionary with him, and we look up the following words: Noah, ark, flood, hero. (For the record, it rained all summer, and I never went back to the gym.)

Week One, Day Two

Today we sign the Language Pledge. The Pledge is one of the defining elements of the Middlebury experience. Its foundational philosophy is that one should be so intensely committed to learning a language that one can and will, for the period of six to nine weeks, forego any contact with the world in any other language but the one under study. As we prepare to sign, I overhear the boy behind me tell the story of an especially serious student who broke her leg the previous summer. Even in the emergency room, he says, she spoke only in Arabic.

Horrified by his tale, I try to figure out how to ask for a bikini wax in Arabic.

In celebration of our last night of freedom, we walk into Middlebury, an irregularly shaped village with one central street running through it, featuring an abundance of shops devoted to both gift cards and athletic goods. There is a single bar, a sort of pub with thumping hip-hop emerging from its basement depths. We duck inside. By the end of the evening, we’ve dubbed it taht al-ard, “under the ground.” Any existential connotations are lost as we find that the DJ is a skinny sixteen-year-old from the local high school playing shuffle with his friend’s iPod. One boy among us, who has spent a summer studying Arabic at the American University in Cairo, requests Amr Diab. “Who?” asks the skinny DJ. “Aaaah-mer Deeee-ahb! You know, Prince of Arabic pop!” Some of the others smile, nodding approvingly. Our DJ doesn’t know him and doesn’t seem to care that he doesn’t know him, either, and we’re left to hop around to Jay Z. Some of us try to belly dance to Beyoncé; others make equally awkward advances toward the townies. Unable to speak anything but Arabic, we smile a lot and use loghat al-jesm, “body language.”

Week One, Day Three

Today is the first day of class. I’m assigned to an over-bright conference room in the university’s library complex. My teachers hail from Iraq and Sri Lanka. Pressed to make conversation, I ask the Iraqi whether it’s true that Saddam Hussein loved Star Wars; I tell the Sri Lankan that I really love the music of MIA. I am very stupid, and they are both very kind to humor me.

We are to introduce ourselves, going around the room one by one. We are especially urged to explain why we are studying Arabic. The motivations are legion. One girl, a native of Vermont, wants to read the Qur’an “à l’originale.” She has the complexion of a peach. There is a graduate student with severe, asymmetrical dark hair who plans to write the definitive take on the politics of garbage collection in Palestine. There is an aspiring foreign correspondent prone to wearing a kaffiyeh about his neck. He writes everything down in a black Moleskine and often throws sympathetic glances at me, the lone brown person in the class.

There is another young woman with a phenomenally tight ponytail who tells us she is studying counterterrorism (from her I learn the word mutarada, “manhunt”). She spent a previous summer copy writing for Al-Hurra, the American-funded television station in Baghdad. She makes me nostalgic for Cold War cultural diplomacy, when they used to send black people to play jazz in faraway places. Everyone likes jazz.

No one likes Al-Hurra.

There is M, a frosty blond forty-year-old with excellent posture who is hard-pressed to smile and tells us she is “between jobs.” Later, we learn that she served at Abu Ghraib in some military capacity. I’m not sure how we learn that — whether this is just a fantastic rumor or is in fact true — but we all make a point of frowning when we see her.

And finally, there’s a fifty-something FBI employee, who’s spent some time in the Middle East. He’s up for a posting as a legal attaché in Baghdad next year and wants very much to brush up on his Arabic. At times he makes Alden Pyle look like Edward Said.

Following introductions, we break for our first evening’s homework, which is considerable.

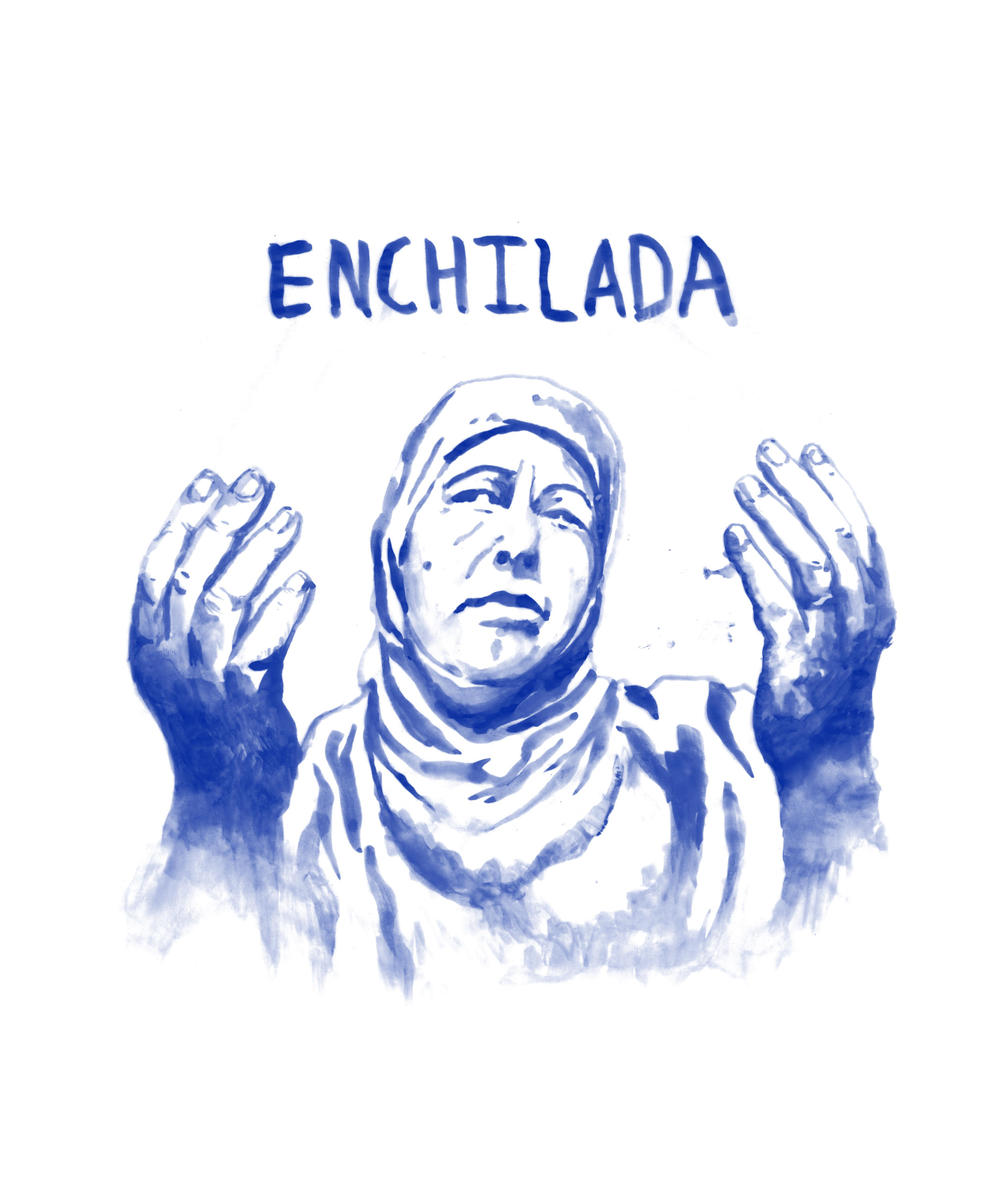

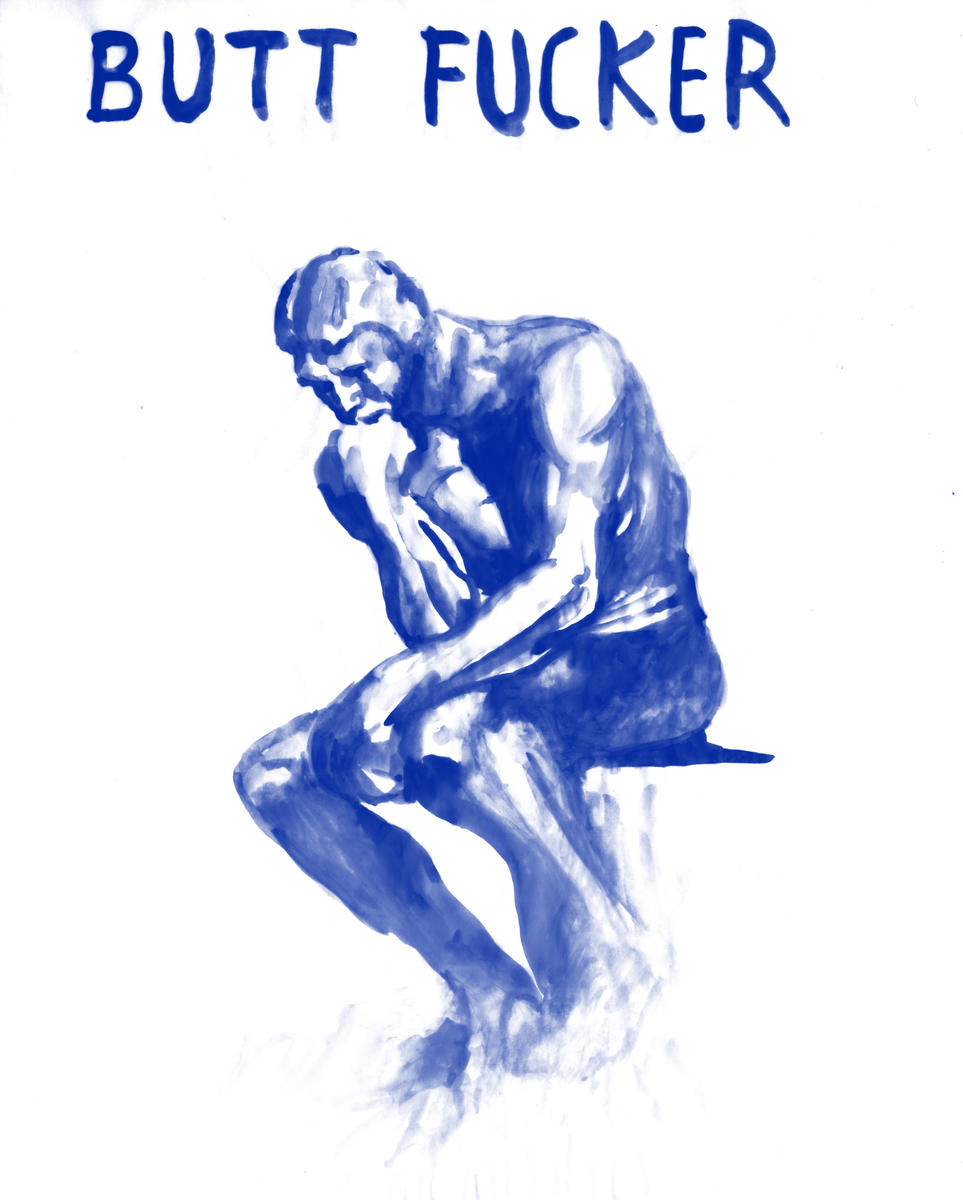

Later, some of us meet at The Grille, the Middlebury campus “bar,” which immediately evokes the camp hokiness of sitcom hangouts like Max’s or the Peach Pit. While H and I are having a drink, a fellow student, a translator from the US Army, joins us. I’ll call him X. From X we learn that the military Arabic-language guidebook teaches students that the Arabic word for “God willing” (inshallah) sounds rather like the “English word ‘enchilada.’” We laugh and decide to come up with some of our own. For example, “I think” is batfakkar, which sounds an awful lot like “butt-fucker.” There is kont (“was”), faqat (“only”), and fartt (“excess”). There are squeals of delight all around the table and rounds of “Ana enchilada butt fucker faqat… ”

I move on to the next table, where a doctoral student studying political science tells me he has spent some time walking the Arab Street. “We must support democratic elections! Blogging is the future! We must support dissidents!” I wonder why he’s yelling. He wags a drunken index finger furiously around my face. As I look down at the table, I realize that he has made a map of the Greater Middle East out of peanuts.

I go to sleep dreaming of Mexican food, knowing the world is in safe hands.

Week Two

I am to perform a skit with one of my classmates, using as much vocabulary as we can cram into ten minutes. Being vain and not belonging to any identifiable clique, I wait until someone invites me. Finally, Joe FBI asks me to be his partner. I can’t help but smile! At his suggestion, we attempt to create a coffee-shop encounter between an American photographer who has just come back from Iraq (him) and a journalist of Iraqi extraction (me). In scripting the lines, I wonder if it might be funny for the photographer-character to have had a grandmother named “Gertrude” — was it not Gertrude Bell who made the map of modern Iraq as we know it? For one second, I worry if he’ll be offended by my little joke. Mostly I’m proud of myself for thinking of it. As we rehearse, he asks me, “Who is this Gertrude you keep mentioning?”

Week Three

I’m called to Dubai for the weekend for a work assignment. I beg the director of the program, a cheery Egyptian man who always speaks into a microphone, even in the intimate space of his own office, to allow me to go away for a mere forty-eight hours on the condition that I not fall behind on any of my homework. After all, I tell him, it’s an Arab country I’d be traveling to. And who would have thought that in 2008 the miserable Arabs would be building the tallest building in the world? We should be proud! After much equivocation, he consents. When I get to Dubai, I find myself struggling with my homework, but I can’t find anyone to help me with it. This being Dubai, no one speaks Arabic. I call H back in Vermont to help me conjugate the irregular verb ta’awwada, “to get accustomed to.”

Week Four

As I return to Middlebury, I find that the entire Arabic School is abuzz with an article that was published in the Washington Post some days before, about Arabic language study in America — specifically, about our textbook, the same book most institutions use: Al Kitab. The author of the article argues that the book’s creators have an anti-Israel agenda. Al Kitab, the author continues, contains subliminal messages littered throughout the text about the wonders of Pan-Arabism. (That part is true: one character reminisces about going to a rally for Gamal Abdel Nasser in his youth — doubtless nostalgic for better, pre-Mubarak days.)

Al Kitab’s pedagogical motif is a cast of characters who introduce the various chapters and vocabulary as their story unfolds. The central protagonist, Maha, is an attractive New York University student of mixed Egyptian-Palestinian origins; she has a bone structure as fine as a cat’s. Her father, a sympathetic man with thick eyebrows, works at the United Nations, while her mother works at the Office of Admissions at NYU. Over the course of twelve chapters, Maha tells us she has few friends, feels neither American nor Egyptian, and is very often lonely. By the end of Book One, it’s hard not to expect that she’ll be betrothed to her cousin, Khaled, who studies commerce at Cairo University and appears in a parallel story line. Khaled, like Maha, is attractive; he also seems always to have an erection, visible through his too-tight gym pants.

I am confused by the Washington Post controversy and try to redirect the discussion at the lunch table to Khaled’s gym pants. In fact, my only critique of the book is that one learns that there are no negatives in Arabic! It’s not until deep into the second book that one learns the word for “bad,” “tired,” “angry,” or even “bored.” This is probably why dozens of beginner students run about Middlebury shrieking “Not great! Not great!” (“Leissa jayed! Leissa jayed!”) when, say, queuing for Tofurkey at the cafeteria, or learning that the dorm bathroom is out of order, or being told they have a quiz the next day.

Come to think of it, what they do opt to include in that first book is curious. According to the elliptical logic of Al Kitab, one should be capable of saying “United Nations,” “senior Army officer,” and “Admissions Office” by the end of one’s first week of study.

Week Five

There is a CIA recruitment session on campus. We receive many circulars and announcements and are given all manner of options as to informational sessions and one-on-one meetings with recruiters. I must go, I tell myself. I am a budding anthropologist, after all. I pull out my pair of khaki pants and hang my BlackBerry around my neck like a fetish. As it happens, there is no room at the secret service — the sessions are already booked up. I see Abu Ghraib M in line for one of the meetings and bunch up my eyebrows, shooting her my meanest glare.

Week Six

Week Six is trying. The equivalent of the famous “sophomore slump.” Schoolwork continues to be harrowing. I am up many nights until 2 am working (mostly shuffling flashcards made minutes before and taking long circuitous walks to the library bathroom). Time for socializing is rare. And besides, one can only handle so many parties built around a game of beer pong — even if it is called Beirut. I am reduced, for the purposes of entertainment, to making eye contact with a Lilliputian boy from the Russian school at the cafeteria salad bar.

As I reach over for a boiled egg one day at lunch, I let my hand brush against his. He says something to me in Russian. I am certain that we have connected. I reply in Arabic, with an innocent query of “What?” in the Lebanese dialect. With its “shhh” sound, I think it very sexy and suggestive. “Shou?”

He repeats the mysterious utterance with even more Slavic oomph. My heart flutters. I am certain he is visually frisking me.

I say it again with more feeling.

“Shooooooou?”

A fellow student from the Arabic school, who studied Russian last year, leans into me and whispers, in Arabic, “You left the egg spoon in the pickle plate.”

Humiliated, I run back to my table.

That weekend, H and I decide to go to a party organized by the Spanish School. He puts on his black dancing pants, and I wear the same thing I always wear but spray some Chanel No. 5 around my arms and head. We agree that if we’re discovered attending another language school’s party, which is a form of breaking the Language Pledge, we will invoke the glories of Andalusia. We arrive at the party to find that all of the Arabic School teachers are there, including the tightly veiled Egyptian. She is dancing to Shakira, her body gyrating in a way that makes us blush. Confused, we go back to Little Gaza to drink.

Week Seven

There is a showdown in soccer between the Hebrew School and the Arabic School. I try not to think too much about the symbolism, but I can’t help but be moved as I see Uri, the hirsute fat kid from the Hebrew school, wrestling one of our teachers, a skinny Yemeni named Omar, to the ground in a rapturous embrace in front of the goalie box. Abu Ghraib M is playing goalie. It’s all very weird, and suddenly I want to cry.

Week Eight

Our weekly guest lecture is by a liberal university professor of Arab provenance. The title of his talk is “Sectarianism in Iraq: Yesterday and Today.” He introduces the history of Iraq in brief, becoming more animated as he tells us about having left the country at the time of the Gulf War, about the Americans’ betrayal of the Shia, and finally, as if climaxing, a slogan: “There was no sectarianism in Iraq before the Americans!” This causes a hullabaloo. I hear short intakes of air from the State Department contingent in the front row. Many, many disapproving heads. The professor grows even more excited, now sweating, building up to a final crescendo, “And the American imperialists should leave Iraq now!”

One of the front row guys, plainly piqued, can’t help himself: “Fucking socialists.”

Week Nine

The end of Arabic School is marked by a talent show. Our class performs a musical, with the FBI guy playing Muammar al-Qaddafi, the hack journalist playing Amr Diab, Clare the pothead playing Margaret Thatcher, the socialists playing themselves. The Egyptian teacher makes a guest appearance as Ustaza Hazzaza, and Abu Ghraib M stars as Bill Clinton, all dressed up in pleather. We take first prize.

Actually, I’m not sure who won the talent show, or even what it was like, as I skipped out to meet the tall Russian at The Grille. Or I studied more for the final exam. Or something — I don’t remember what I did, to be honest, just that I didn’t want to be caught singing in public, dead or alive. I do know that I used the word batfakkar at least three times that afternoon. And that I will never be so good a grammarian in my life, in Arabic, as I was that day.

The story of “the permanent exhibition of arts and crafts and cultural heritage of the captives of the holy war and their ways of living, hygiene, and treatment,” goes back to the early years of the Iran-Iraq war, with the establishment of what was intended to be a temporary camp for Iraqi prisoners at the Heshmatiye military base east of Tehran. In those days, Heshmatiye was a beautiful place, with flocks of birds and tall trees. It was not at all like a POW camp as you might imagine it, not least because the soldiers had not been specially trained to deal with prisoners of war, which seems to have made it easier for friendly relationships to develop between guards and captives.

Among the early arrivals was an artist named Ostad Monghaz. Monghaz had been a professor of sculpture and painting at a university in Italy. The unlucky professor, who returned to Iraq to see his family, was forced by the Ba’athist regime to go to the frontlines for propaganda purposes. During his initial interrogation at Heshmatiye, it became clear that he had no political record in Iraq and had simply been caught by accident. But war has its own rules, and the professor had entered the camp as a prisoner. There wasn’t much that could be done for him. Still, Monghaz managed to make art in the camp, thanks to the martyr Mohammad Ali Nazaran, for whom the base is now named.

At the time, Nazaran was the head of the Prisoners of War Commission and, he created an uncommonly pleasant atmosphere for the captives. Despite the ongoing war, Nazaran somehow secured the necessary permission for the families of many of the captives to come and visit their sons and husbands in Iran. This was exceptional not only in the context of this war, but also in the history of war. His compassion gave the Iraqi captives hope. Even after his death, his memory was kept alive in the minds of Iraqis.

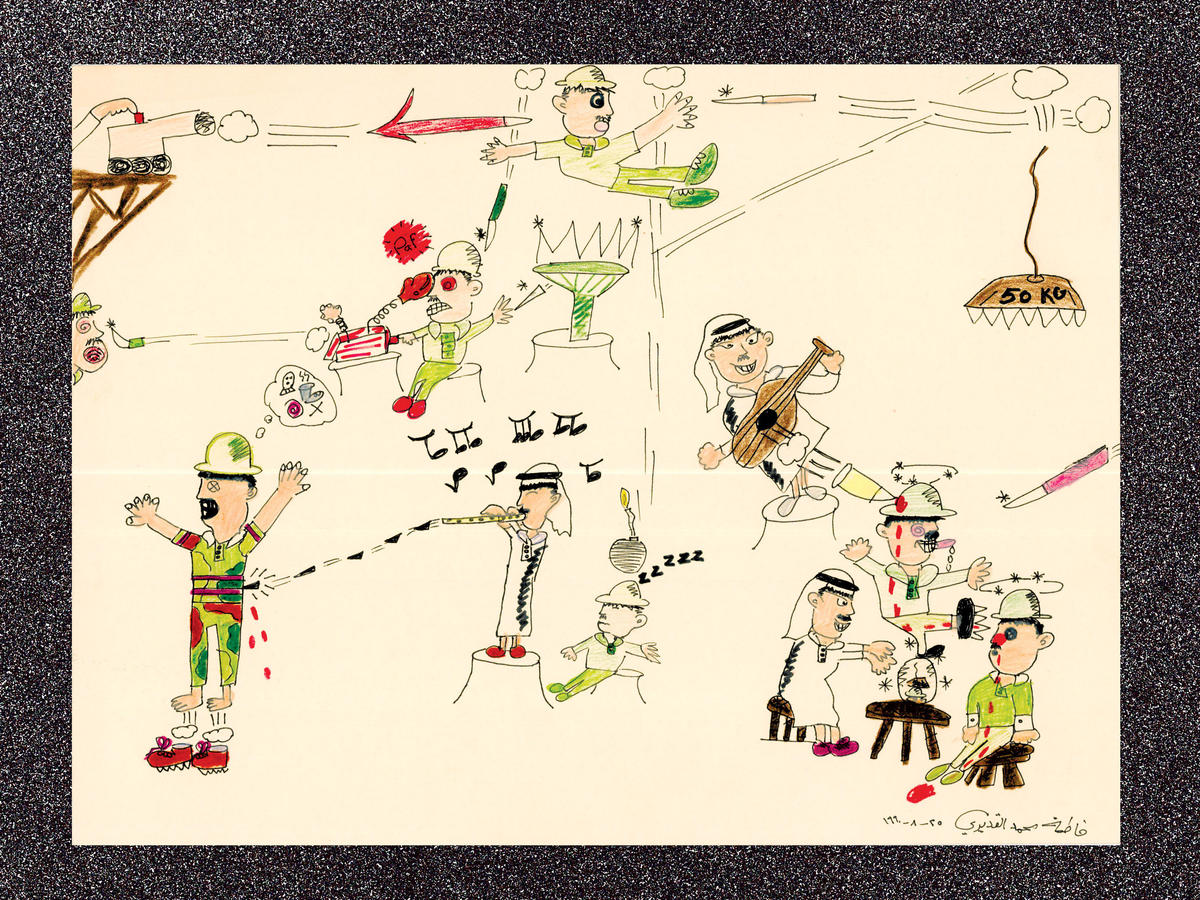

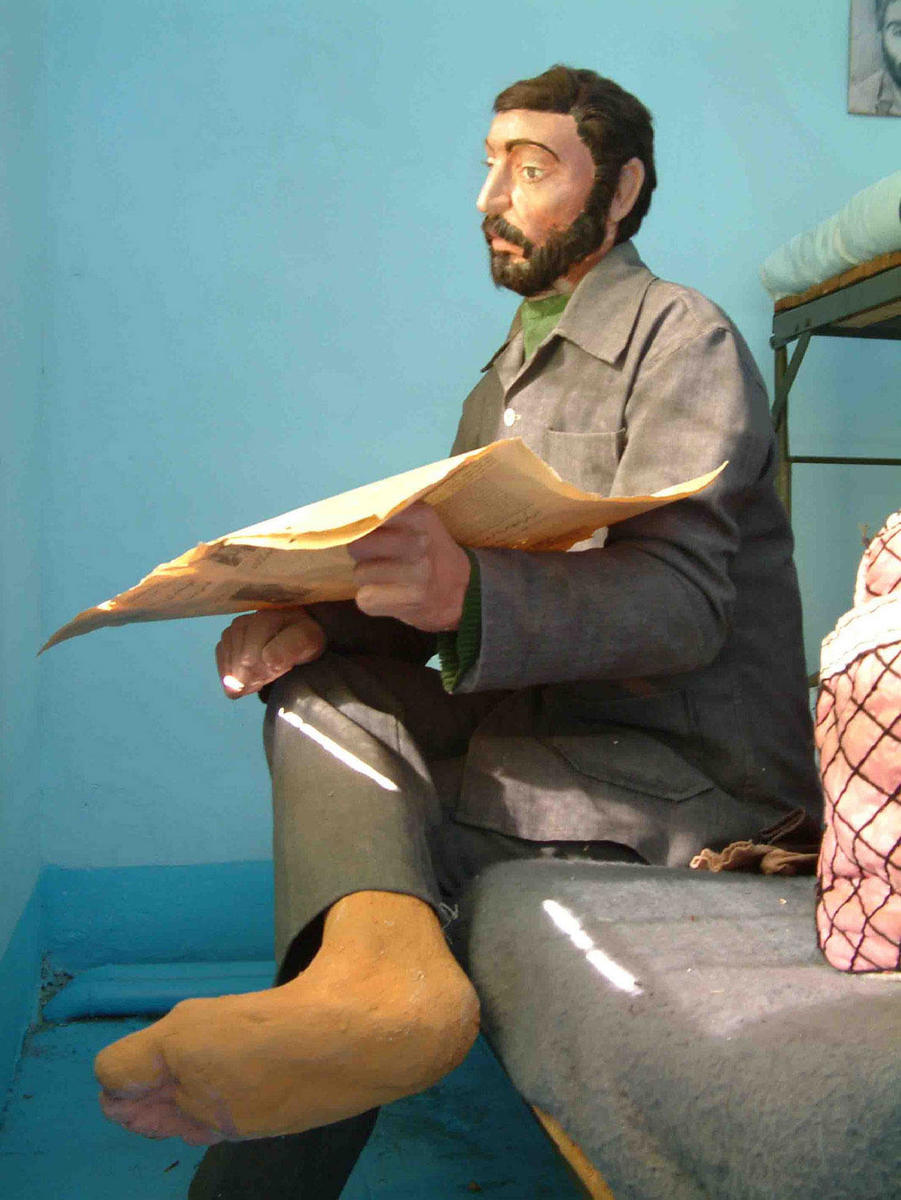

In 1990 and 1991, as the issue of prisoner exchange came to the fore, the question of how and whether to preserve the prisoners’ works was brought up. Over the course of four years, and through evaluation sessions of the prisoners’ artworks by the Committee of the Prisoners of War, those responsible for the camp agreed to build four halls, containing sixteen rooms, to exhibit and preserve the paintings, calligraphy, woodwork, needlework, and sculpture produced by the POWs. This was a great victory for the captives who came to this camp in their youth and now had to leave it. The new museum would showcase the creativity and humanity of the captives — and also of the captors. The camp itself was part of the exhibition. One of the former captives, an aging engineering graduate named Medhat Hosseini, stayed on, building delicate life-size sculptures from available materials — construction plaster, sometimes even dental plaster. These figures recreated life in the camp for visitors. There were even figures of Saddam Hussein or King Hussein of Jordan.

But in the decade and a half since the end of the war, the museum had few visitors beyond Red Crescent representatives, the occasional politician, and tours of distracted schoolchildren on the anniversary of the Iraqi invasion. Most people were unaware of its existence. Over time the number of staff at the museum was cut to a minimum. Soldiers took over the job of cleaning and maintenance, and many of the most powerful works made by the captives were damaged or simply suffered because of poor preservation. These days, Hosseini wanders around repairing sculptures, kept company by an old cat.

In 2008, a huge highway project was announced that would run straight through the museum site. A concrete wall was erected on the eastern part of the base for security purposes. Gone were the beautiful pine trees that surrounded Heshmatiye. Already a large part of the camp is used to collect urban and industrial waste.

Soon after, the Tehran city council passed a law requiring all military camps to be removed from the immediate area. Today the museum is awaiting its destruction.

Soon, beneath a mass of dust and concrete and the yellow lights of the highway billboards, the stories of 57,000 Iraqi soldiers who once lived on these grounds will lie buried and forgotten.

In 2007, Vahid Zare Zade directed a short film about the museum called POW 57187.

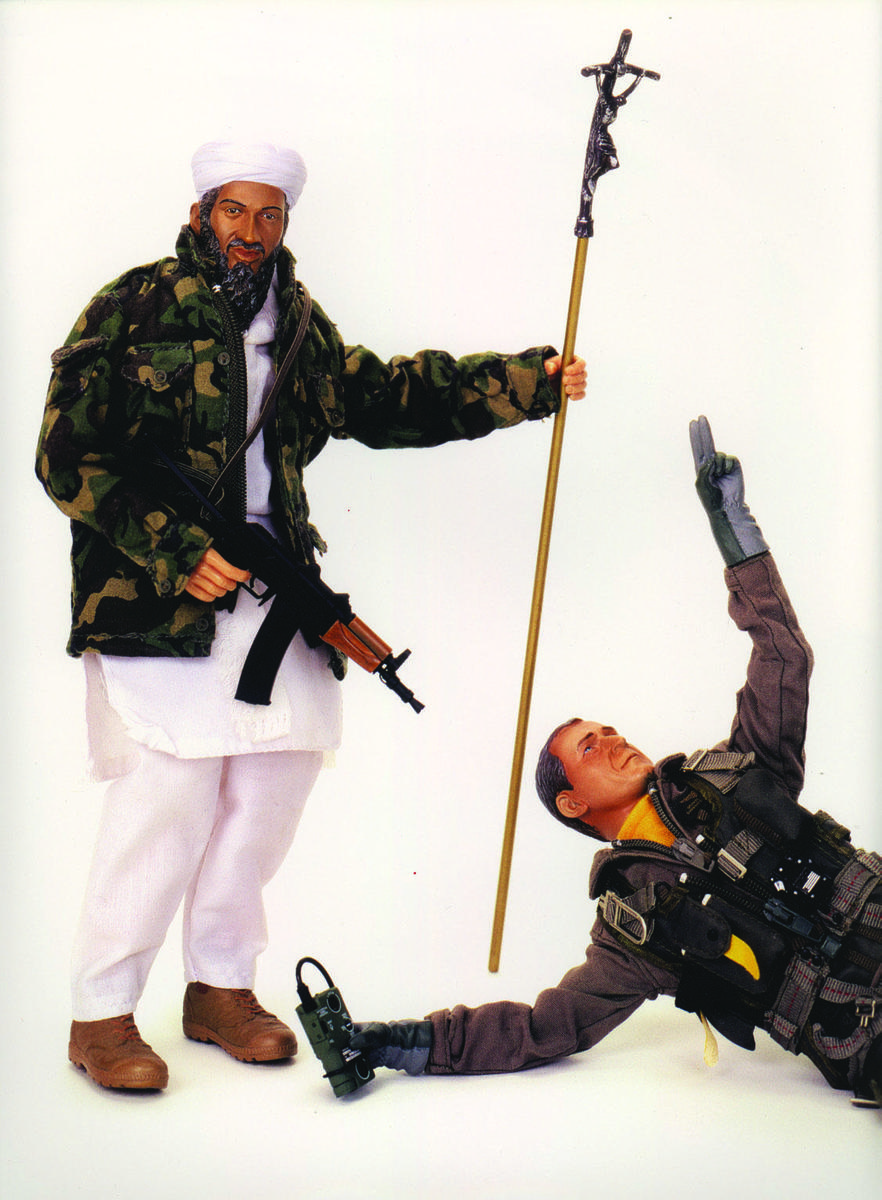

The first time I met Selim Varol, the man they call the Toy Giant, I was expecting him to suck. I hadn’t really had many toys as a kid, and at a very early age I’d adopted the punk/skate ethos of “property is theft.” At the front of my small vinyl record collection sat Poison Idea’s Record Collectors Are Pretentious Assholes EP, and when I encountered the wide-eyed, Cheshire-cat-grinning, combat-fatigue-wearing Turk at a group art show in Barcelona, before we spoke, I couldn’t help but think the same of vinyl toy collectors, too.

We were both exhibiting in the show, but the organizers didn’t know how to use their video camera, so I got roped into shooting interviews. Selim was my first victim, and as he launched into a heartfelt and surprisingly eloquent treatise on toys and wonderment and the importance of cultivating one’s inner child, I started to think I might be the pretentious one. Here was a crazy collector — his toy collection may be the world’s largest — who was adamantly opposed to keeping anything in a box. Since then he has published a book of tableaux featuring his vinyl figures, ToyGiants, with photographers Daniel and Geo Fuchs, and created a roving conceptual gallery, artempus, to showcase his collections and enthusiasms, which are legion.

Monihan Monihan: How many of these toys do you have, Selim?

Selim Varol: Fifteen thousand? Maybe? I don’t actually know anymore…

MM: How did you get started?

SV: When I was six years old, I was completely blown away by the first Star Wars movie. We were on our yearly holiday trip to Turkey — I was born in Izmir, but we moved to Germany when I was two — and my parents took me to an old-school open-air double feature. The second movie was Alien. I remember running away during the first creepy scene.

Alone, psyched by Star Wars and shocked by Alien, I pissed my pants on the dark walk back to my auntie’s house, where we always stayed. It must have had some effect because to this day I have lots of Star Wars and Alien toys.

MM: But not the original ones, right? I’ve heard you talk about another pivotal incident in your life as a collector.

SV: Yeah, I came home one day, entered my bedroom, and all my childhood heroes were gone. My parents aren’t sure anymore which of them did it, but in any case the message was clear. This was it — time to grow up. I think I was twelve years old, and I can remember that moment like it was yesterday.

MM: You did not grow up.

SV: I proceeded to buy back all of my favorite pieces, one by one, over a period of time. And then I kept going. By the time I realized what I was doing, I was well into my long completist period.

MM: What was that?

SV: For example, I didn’t just get my Star Wars figures back — I tried to get every Star Wars toy ever made. Which might entail running to every flea market in town, or driving to toy conventions, or flying to toy conventions. Or… seeking out old toy manufacturers’ production samples and molds.

Looking back, that completist period was the most boring time of my life. It was like I had a full-time job as an archivist. Today I only buy things that I like and that somehow round out my collection as a whole.

MM: Are your parents collectors of any sort?

SV: No, my parents never collected anything. I mean, my dad is a bit of a pack rat, he can’t throw anything away. So that’s sort of collecting. But as Gastarbeiters (guest workers) we weren’t the richest people around Duisburg Bruckhausen, the industrial area where we lived. Both of my parents were working hard.

MM: Not to psychoanalyze you or anything, but where did this obsession come from? Were you particularly alienated as the child of guest workers? Were your “childhood heroes” like friends or trustworthy companions you could rely on when real friends were few and far between? Like Linus and his security blanket?

SV: To be honest, I never had big problems being a foreigner in Germany. It was more a question of money, I think. There was a kid in the neighborhood named Oliver who had all the Star Wars toys. That was something my parents just could not afford. Part of my collecting habit is definitely rooted in the fact that once I started earning money, I had the opportunity to buy all the stuff my parents couldn’t buy for us when we were kids.

MM: Could this sustained infatuation with toys be characterized as an attempt to reclaim your lost youth?

SV: Not really — I think I’m still young! As Andy Warhol said, since people are going to be living longer and getting older, they’ll just have to learn how to be babies longer. I don’t see my faith in playing as some sort of bizarre contrived antidote to lost innocence. I just truly believe that playing keeps you creative, young, and sociable.

MM: So in addition to your toy collection, you have a sizable collection of contemporary art. And an itinerant art gallery in Düsseldorf in which to exhibit your stuff — toys, sculptures and photographs alike. How did that happen?

SV: The transition was pretty easy. My art collection started with “art toys” that clearly related to the kinds of toys I’d loved as a kid. And over time the “art toys” I was collecting became widely accepted by the contemporary art scene. With artists like Murakami, KAWS, and Michael Lau initially leading this development, it seemed to happen pretty naturally. But I think the urge to make art and the urge to make toys are the same. The new medium of easy-to-sculpt materials, like vinyl, just accelerated this phenomenon, in that it made it affordable for everyone to work on small sculptures on a larger scale. And I don’t think that it will ever go away — we humans will keep playing till we die!

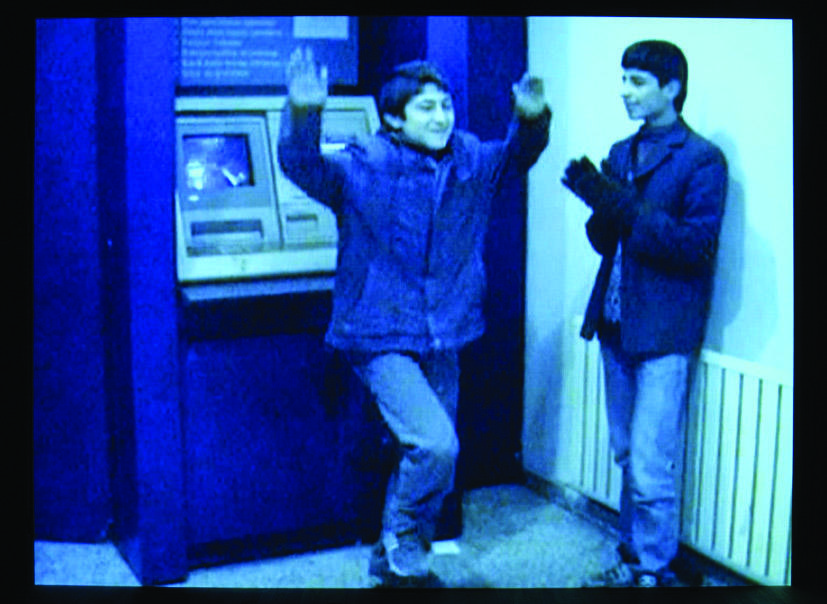

If you happen to find yourself on a Tehran avenue in the coming months, you may notice a passenger with a video camera in the backseat of a motorcycle taxi, interviewing the driver. Listen closely and you might catch a snippet of intense discussion over the purr of the bike’s motor. Wear something especially eye-catching that day, and you might even stand out in a frame of Tehran-based artist Shahab Fotouhi’s current video project, Third Case.

Third Case draws its subject, structure, and title from the 1979 film First Case, Second Case by Iranian auteur Abbas Kiarostami. Kiarostami’s film teases the allegorical implications out of a banal primary school incident in the context of the nascent Iranian Revolution. A teacher draws a large ear on a chalkboard. While his back is to the classroom, a student talks out of turn, disrupting the lesson. The teacher demands that the student identify himself, and when no one comes forward, he removes seven students from the class for further questioning. The film then presents two scenarios — cases, as it were — one in which the students refuse to name the guilty party and are all punished by being kept out of the classroom, and another in which one student identifies the culprit and is allowed to rejoin the class. Kiarostami interwove these two staged scenes with documentary footage of interviews in which he fielded reactions to the two cases from various adults, including newly minted officials of the revolutionary government. Many of the respondents Kiarostami engaged read the scenarios as parables of loyalty, condemning collaboration with the Shah’s secret police and pitting the nobility of silence against the weakness of informing, a reading which was undoubtedly aided by the conspicuous, slightly surreal, image of the ear on the board, drawn by the most potent authority figure in the film. (In spite of these anti-Shah interpretations, the film was banned by the new regime for its allegedly subversive content and for representing the opinions of figures from banned political organizations, such as the Communist Party.)

As his title suggests, Fotouhi’s Third Case presents a new option. Following a logic of substitution, he proposes the very same ethical classroom scenario, dramatized in First Case, Second Case, to motorcycle taxi drivers ferrying him around the city of Tehran. “The working class can give more interesting answers,” Fotouhi recently told me. “And after thirty years of transformations in society, these answers are more complicated.” Third Case doesn’t introduce a new scenario into the ethical dilemma, but instead reconfigures the terms of the documentary itself. In revisiting Kiarostami’s film and looking to workers such as taxi drivers, instead of politicians with big names spouting official discourse, Fotouhi is endeavoring to produce a remake in the strongest sense of the word — a work that is both a picture of the present in all its ambiguities and a trenchant critique of the past. By reassessing the binary logic and revolutionary clarity that structure Kiarostami’s film, Third Case promises to confront the predictability of the original film’s responses with the volatile contingencies of class, history, and public space — thus providing a framework for the political anxieties of Iranians today.