Reza Abdoh pushed his actors — and audiences — to their limits amid ambitious, unusual, disorienting sets. Often staged in abandoned warehouses, seedy motels, and city streets, his plays were as disturbing as they were enthralling. Scenes of violence, ridicule, obscenity, and ruin were performed without intermission at a machine-gun pace. Abdoh’s aesthetic language evoked the disjunctive modes of the theatrical avant-garde while embracing fairy tale and folk dance, BDSM and queer club culture, cable TV, and music video, as well as decadent poets, court documents, sitcoms, and vaudeville.

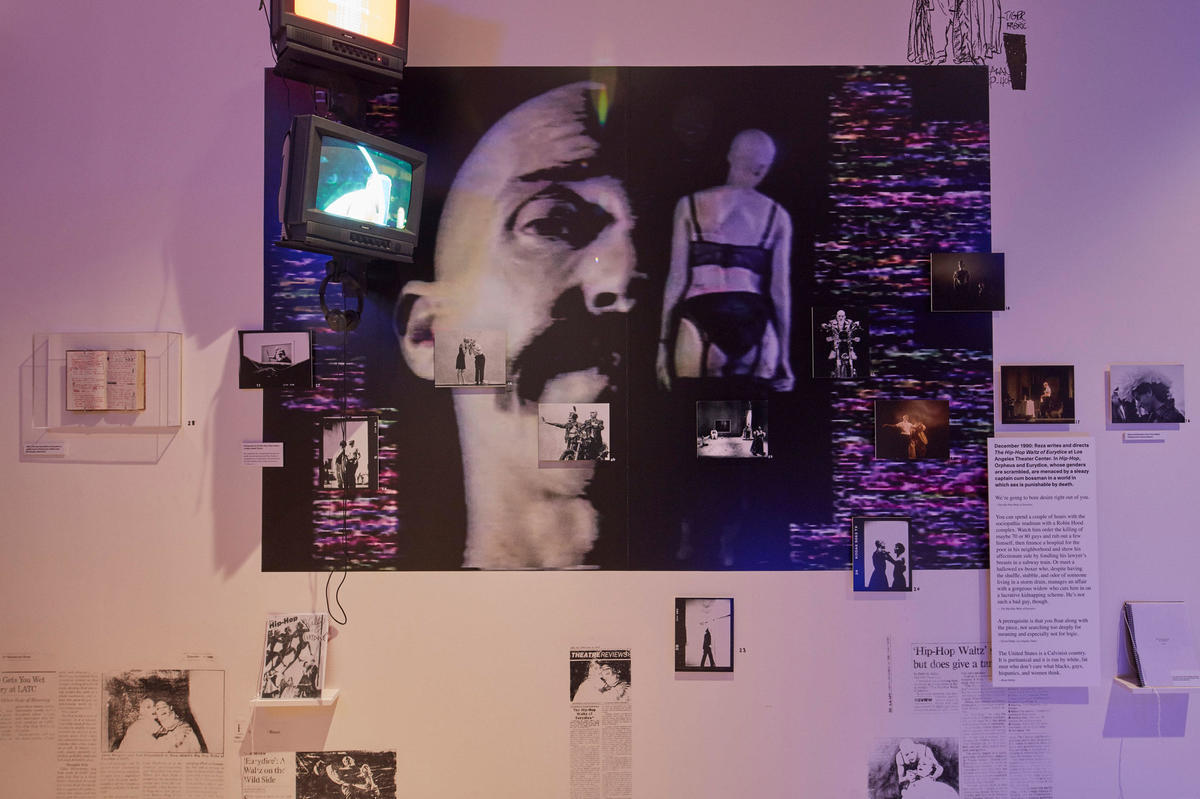

Abdoh’s theatrical works — produced by an artist literally racing against time while dying of AIDS — never shied from the hard things. His plays considered corporate greed and environmental degradation (Minamata); sexual repression and the fascism of everyday life (The Hip Hop Waltz of Eurydice); the disintegration of the family (Bogeyman); celebrity, atrocity, and homophobia (The Law of Remains); racism and American identity (Tight Right White); xenophobia and genocide (Quotations from a Ruined City). A final play, The Story of Infamy, which twinned the lives of a prisoner languishing on death row and a man afflicted with a terminal illness, was never produced.

The AIDS crisis was both subject and metaphor for Abdoh’s work. A plague that for a brief moment killed all of its victims indiscriminately — regardless of race, gender, age, income, or nationality — formed the crucible through which Abdoh made common cause against his time. The virus revealed the pastoral brutality of 1980s and 1990s America through the daily lives and agonizing deaths of a generation of gay men, set against the malign neglect of Presidents Reagan and Bush.

Co-organized by Klaus Biesenbach, Director, MoMA PS1 and Chief Curator at Large, The Museum of Modern Art; Kirst Gruijthuijsen, Director, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, and Negar Azimi, Tiffany Malakooti, and Babak Radboy for Bidoun. The exhibitions staged at MoMA PS1 in 2018 and KW Institute of Contemporary Art in 2019, represented an effort to capture something of the intensity, verve, and anger that were so critical to his work.

One of the most abiding themes in Abdoh’s art was family. In organizing the exhibitions, we came to know and rely upon Reza’s motley “tribe”—friends and collaborators, siblings and cousins. Two people deserve special mention. Brenden Doyle, Abdoh’s partner, muse, collaborator, and caretaker, was unstintingly generous with his time, memories, and insights; without his blessing, this project would not have been possible. We relied, too, on Adam Soch, whose video documentations are the indispensable record of Reza’s productions, and whose film, Reza Abdoh: Theater Visionary (2015), is an inspiring tribute.

Just before his death, Abdoh gave instructions that his plays never be performed again. Perhaps it’s fitting, then, that his work should recirculate in a context he would likely never have imagined: the art world. Abdoh’s angry, purgative, humanist work speaks all-too-vividly to the present day.

Among the tragic ironies of Abdoh’s life and death, there is this: had he lived just one more year, it’s quite likely he would still be alive today. (Abdoh died in May 1995; the death sentence of AIDS began to lift in 1996, with the widespread introduction of combination antiretroviral therapy.) Many have speculated about what might have been — the fame and acclaim he might have found as a filmmaker or poet. But we believe that it’s crucial now, almost twenty-five years after his death, to remember what he did.

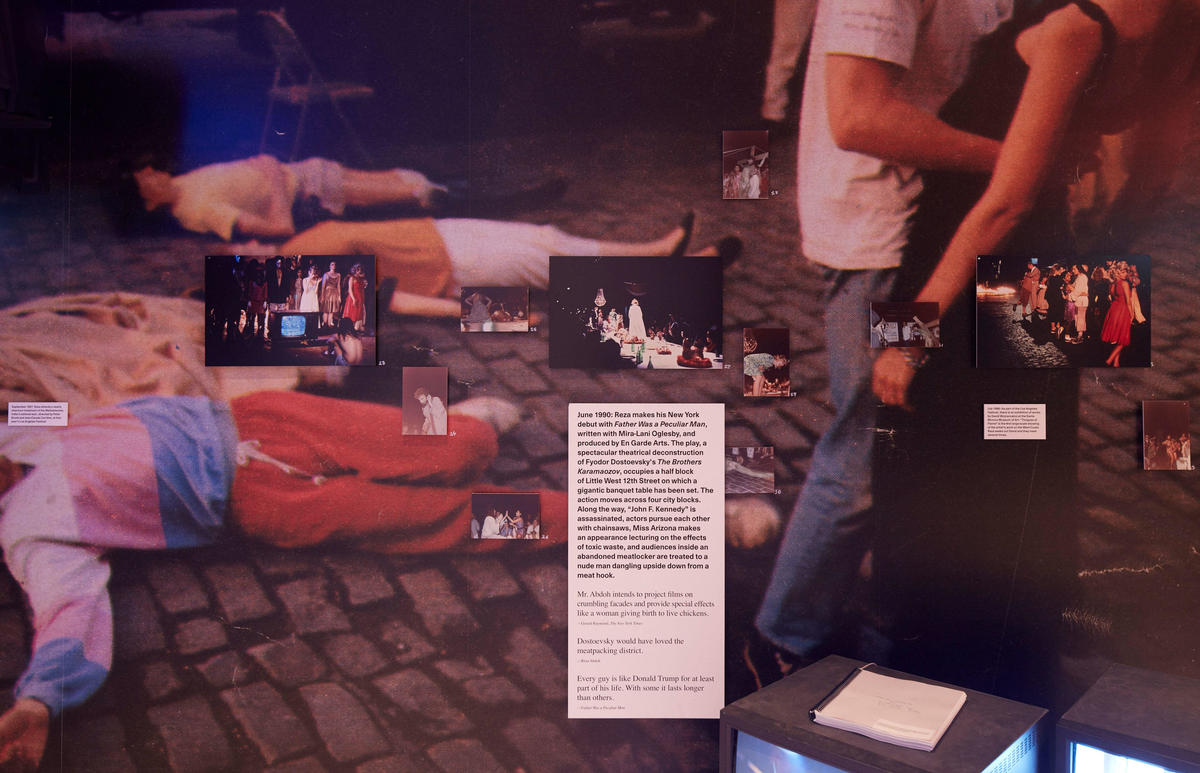

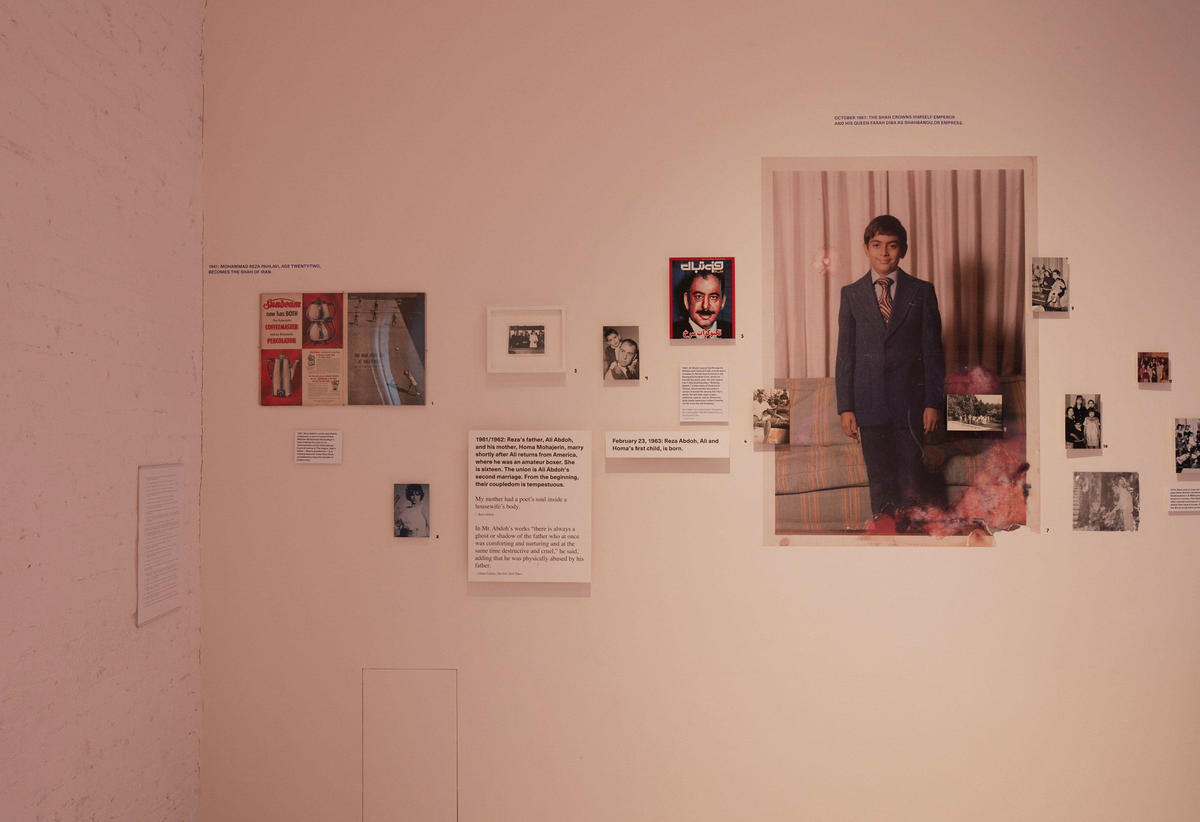

Installation views, MoMA P.S.1:

Installation views, KW Institute for Contemporary Art: