The Al-Hamra has become an Iraqi icon — part hackneyed myth, part hardened reality. This hotel, in the Baghdad neighborhood of Al-Jadria not far from the banks of the Tigris, is where you could once find a cosmopolitan lounge band playing Sinatra on Thursday nights and still get a quality gin martini at the bar. That was back in the day when Saddam was somewhat softer and architect Robert Venturi was running around town fulfilling the mustachioed president’s every whim. More recently, the Hamra is where Iraqi exile Kanan Makiya hid his family’s art treasures, where the lead singer of an Iraqi boy band would hang out on Friday afternoons and, finally, where a young activist named Marla Ruzicka would throw her famous pool parties for the influx of peoples, foreign and Iraqi alike, who arrived with the fall of Baghdad. Until recently, one could find Muqtada al-Sadr’s followers pacing about outside the Hamra’s walls, hoping to make a buck as a guide, guard, or driver. A handful of beggars and the occasional prostitute also marked the surroundings, while some particularly entrepreneurial Iraqis offered the most gullible of foreign visitors the chance of a peek at the “secret archives” of the fallen despot.

During the early days of the Occupation, the Hamra was among the top draws for accommodation. While the Palestine and the Summerland were somewhat swank — for Coalition stars and the like — the Hamra seemed to attract a more idiosyncratic following. Its Christian Iraqi owners had fled to Amman with the invasion, and the hotel’s new owners capitalized on the arrival of press corps and aid workers who had come to be a part of history made. Rooms cost upwards of $150, with little obvious justification. Some sought shelter at the neighboring Karma or Doulaime hotels — less known and certainly far cheaper.

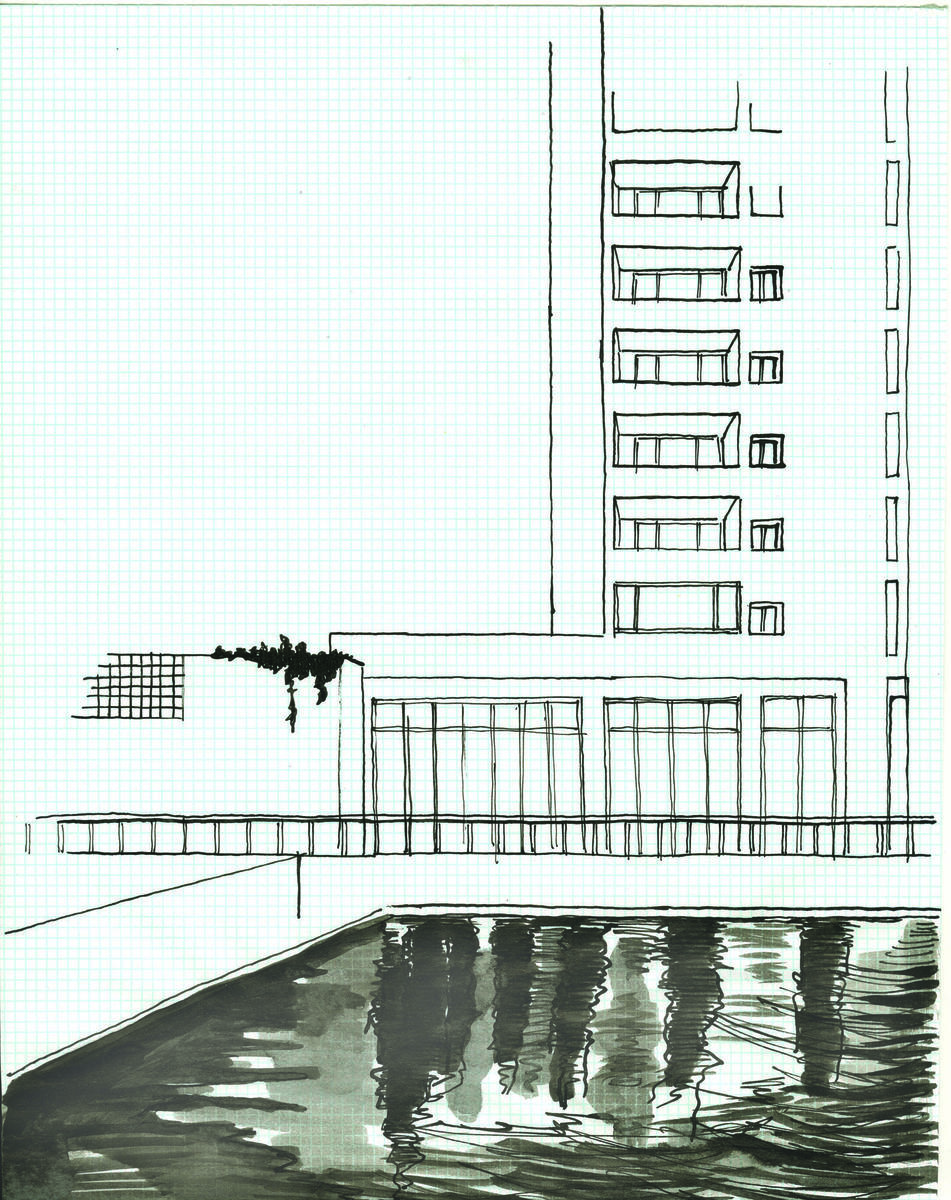

Arguably incongruous with its surrounds, the Hamra boasted a pool situated between the two towers that define its structure — perhaps a rarefied vision of a Florida spring break destination or a broken Club Med. Marla, who died in a car blast last spring, could be found swimming laps in the pool by day and hosting parties for hotel guests and their buddies by night. For a minute, you could have oddly been anywhere but there — save for the enormous protective wall that marked the pool’s perimeter.

In the lounge, Samir, a Christian Iraqi in his fifties — part vagabond and very much old playboy —would sit behind the piano with a Camel cigarette dangling from his mouth. He spoke English with an Italian accent and had studied music in Italy and Hungary. Many years ago, he had been the chief pianist of the Baghdad Sheraton and, on the side, gave piano lessons to the sons of ambassadors — and not infrequently, we were told, made love to their wives. Later, he fought in his country’s nine-year war with Iran, and you’d notice the signs of a trauma that lingered if you spoke to him for just long enough. Nevertheless, at the post-Saddam Hamra, Samir always managed to stir up a crowd with his epic comb-over, old world air and the performance that came with it. At times, all of this seemed a bit like journalists playing in an amateur high school version of Casablanca, but it served to distract and entertain all the same.

Evenings at the Hamra’s restaurant brought together a funny bunch. You could very well be seated next to group of Iraqi businessmen in search of juicy American contracts, the Mayor of Baghdad, an analyst from any one of myriad democratizing outfits or, as I did one day, a hired killer. At the start of the Occupation, some savvy French journalists managed to dig up glorious wines from Saddam and Uday’s subterranean vaults, though those quickly dried up and yielded the foul Lebanese and French variety. The hotel chef, however endearing, overcooked the spaghetti. The “Special Chinese Rice” was short of special, and hamburgers came complete with a fried egg inside. The French fries, nonetheless, were delicious.

Eventually, the Hamra became a world within a cracked world. Stepping outside of its vacuum-sealed confines, one would encounter a gigantic white mesh cage. Guards manned the entrance twentyfour hours a day, scanning for things-dubious in the Green Zone’s unknown. The hotel eventually became packed with foreign mercenaries — “private military contractors” is perhaps the more politically correct term, but they were mercenaries all the same. Soon enough, you could find yourself crammed in the hotel’s small elevators with a beefy Serb, Croat, South African or perhaps an American — each with enough artillery to hold out against Saddam’s national guard for a week. It wasn’t long before the sign that read All Weapons are Forbidden in the lobby became an old joke.

Today, the Hamra’s chef has left the hotel — most likely working for the coalition somewhere in the Green Zone (if he is in fact still alive; he had received more than a few death threats during his tenure at the hotel). Last we heard Samir was in Jordan, jobless and awaiting news on a visa application he filed some time ago to travel to the States. Back at the ranch, the mercenaries remain and the foreign press corps have set up mini-fiefdoms within the hotel’s rooms — marking their territory with satellite phones and high-speed internet. Some of them may spend six months in Iraq without exiting the compound once, save trips to and from the airport in armored vehicles. Tales of kidnappings are more than enough to convince them of the merits of staying indoors. Some days you may find the more ambitious among them scaling the hotel’s fire escapes for a bit of exercise. Perhaps you could say their vision of Iraq is a bizarre one — limited to little more than the four walls of the hotel room and an endless stream of images of that which occurs in an invisible outside. At the Hamra these days, “Reporting live from Baghdad” has taken on a whole new meaning.