New York

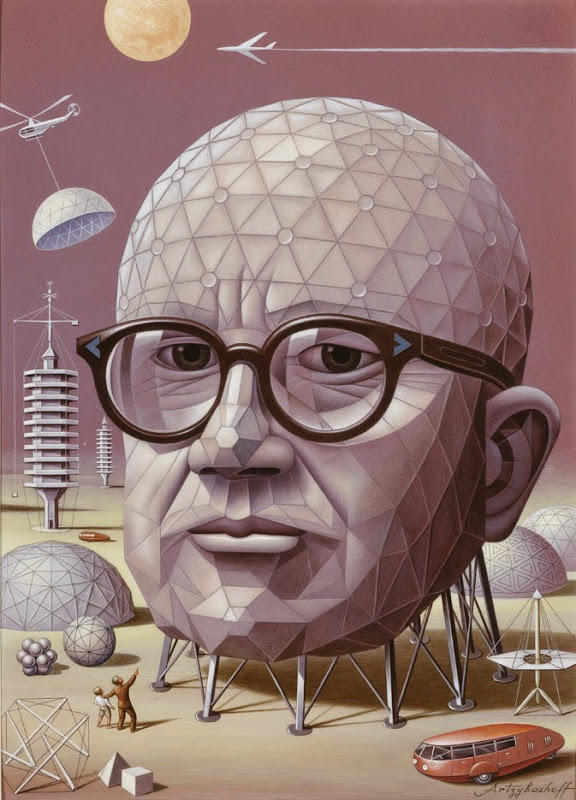

Buckminster Fuller: Starting With the Universe

The Whitney Museum of American Art

June 26–September 21, 2008

It was on the coral island of D’Arros in the Seychelles Archipelago, in February 1978, that Prince Shahram Pahlavi of Iran, nephew to the last shah of Iran, convened a meeting of fifteen of the world’s foremost environmental advocates. Their task? “To develop a strategy for preserving the earth.” The Very Reverend James Parks Morton recalled of then-eighty-three-year-old Buckminster Fuller, “Bucky on the subject morning, noon, and night, was overwhelming.”

In addition to seeing him at our group gatherings, which Bucky dominated, I met with him privately… I asked him how we should continue building New York’s Cathedral of St. John the Divine for the solar age.

By the time we left D’Arros, Bucky… had volunteered to plan with me over the next few months how to complete the cathedral as a vast solar bioshelter to export solar energy to the local community.

The great polymath Fuller visited Morton some months afterward and delivered a sermon from his pulpit, expounding on the idea at length; but in the years that followed, the plan was substantially reduced in scale. Today, St. John the Divine, the church of Morton’s parish, is still under construction, though its present design doesn’t call for the bioshelter conceived on D’Arros. At the time of Morton and Fuller’s meeting, mass demonstrations were already underway in Tehran. In a little less than a year, their host, along with his uncle, would be exiled from Iran.

The D’Arros episode brought together a number of set pieces from the Fuller drama, as typically staged by his critics — the speechifying, the starry-eyed client, the big zilch at the end. In this instance, however, there was the added intrigue of a political environment so grave and (in hindsight, at least) so obvious, that it turned the whole production into a farce. There was Bucky, scheming under the banyans as the world burned! Known as a visionary in the fields of design and engineering, Fuller was afflicted from childhood with bad eyes, and perhaps his shortsightedness extended to politics, as well.

That’s a serious charge: Fuller’s reputation as a technological utopian, his counterculture cred in the 1960s, even the common gripe of his detractors that he was too ambitious, all have rested on the presumption that Fuller was, if not strictly engagé, at least an authentic radical. But what if the famous revolutionary wasn’t revolutionary enough?

That Fuller rarely paused to consider the possibility of a meaningful resistance to existing political conditions shouldn’t be news. Still, architect and critic Felicity Scott, in her recently published Architecture or Techno-Utopia, makes it a revelation: Scott perceives a politically regressive paranoia at the heart of Fuller’s world-saving project. It’s an important point, too, because it upends the prevailing arguments both for and against Fuller — all of which have become rather tiresome. Fuller is one of those cyclical saints to whom architects start praying once every few years, only to be forgotten again. Right now we’re witnessing one such turn of the wheel.

The latest Fuller moment began, by rough estimate, in 2006, around the time of the exhibition Best of Friends: Buckminster Fuller and Isamu Noguchi and was sustained by the recent environmental fetish in architecture. It came to a head this past summer, with Fuller shows at Max Protetch, Carl Solway, and Sebastian + Barquet galleries and a series of events at the Center for Architecture in New York; it reached its apex with the exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, Starting with the Universe, which closed September 21.

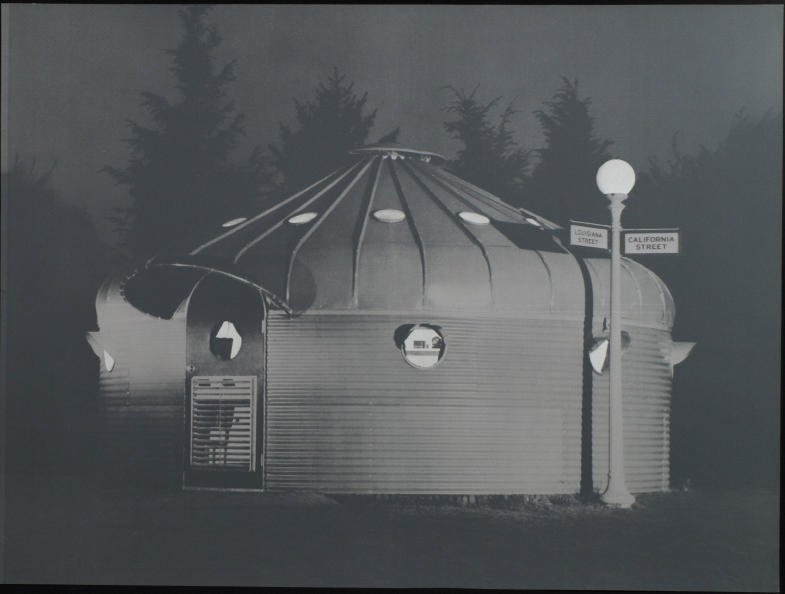

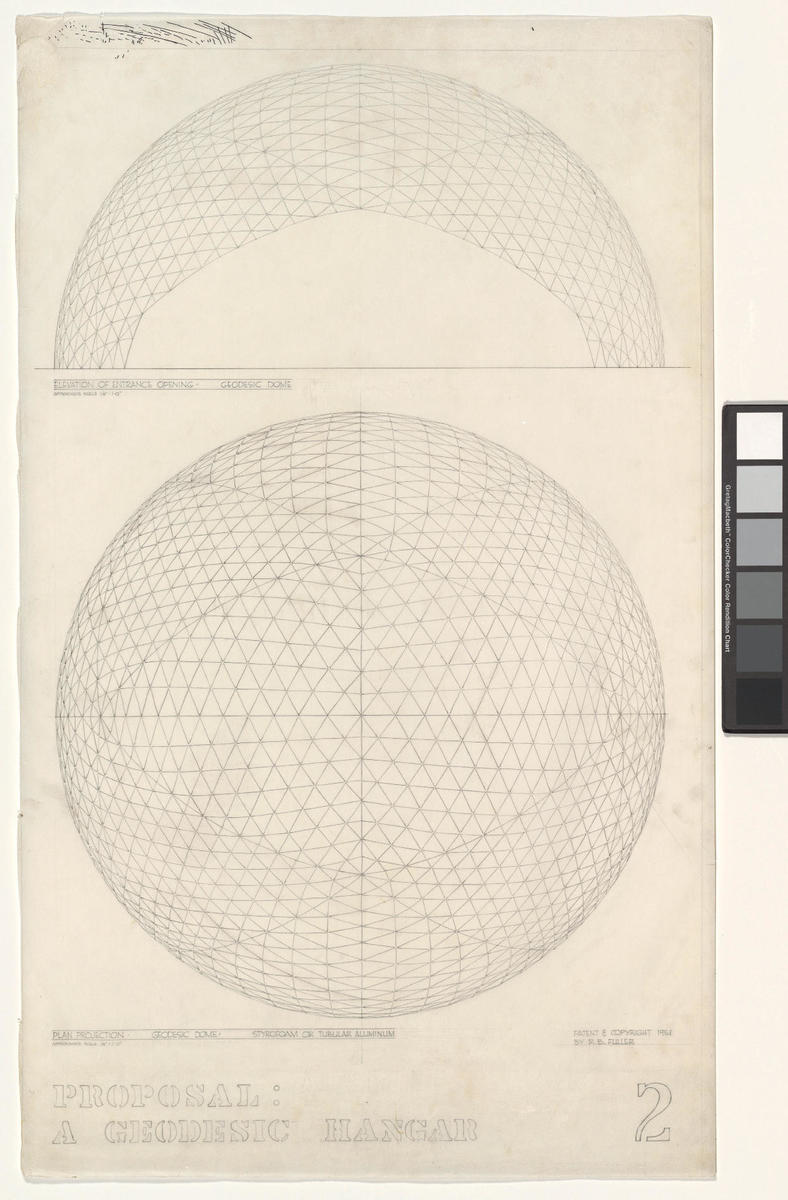

Many of the works on paper at the Whitney were splendid: early graphite plans for the proposed Dymaxion Dwelling Machine; a screenprint of Fuller’s Synergetic Building Construction system, featuring the design schematics against the background of a New York streetscape; the Harlem Redesign of 1965, giant cylindrical pylons spaced at intervals over Upper Manhattan, manifesting the mutual influence between Fuller and Louis Kahn. There were a few surprises, as well, in particular a Collector’s Room designed for architect Ely Jacques Kahn (no relation to Louis), whose relationship with Fuller might warrant further study. But too many drawings and renderings took the life out of the exhibition, occasionally recreating the atmosphere of a taxidermist’s lab. There was of course the familiar MoMA Dymaxion House model, along with a Dymaxion Car from the Harrah Collection in the main floor gallery and any number of smaller models and structural elements besides. All in all, the show felt dutiful, relevant, and dull.

“Relevant” was the theme of Nicolai Ourossoff’s review for the Times, though he hardly confessed any opinion about the quality of the curatorial work. The Whitney got its kindest critique from Alistair Gordon of the Architect’s Newspaper, a reaction made only slightly suspect by the fact that Gordon’s most recent book is a celebratory volume on mid-century experimental design. The takedowns came, predictably perhaps, from the New Yorker’s Elizabeth Kolbert in an unflattering June 9, 2008, Fuller profile and from Martin Filler of the New York Review of Books in October, who not only tied Fuller and his chicanery to a lamppost but put the show’s curators, K Michael Hayes and Dana Miller, there as well.

Hayes, at least, probably had it coming. His essay in the accompanying catalogue is remarkable chiefly for its credulity. While Hayes recognizes that architects of today should not look to Fuller for “reflexivity… or radical cultural critique,” he doesn’t care to admit just how profoundly un-reflexive Fuller really was, or what repercussions that uncritical posture had for architects of his day or ours. Rather than taking Fuller for either a genius or a charlatan, we might, like Scott, detect in him a foreshadowing of some of contemporary architecture’s latent contradictions: its best minds wandering among imagined solutions conjured in idyllic isolation. They might as well be on D’Arros — in fact, they could be. The prince still owns the island, and it’s available for rent at $7,500 per day, all inclusive.