Under the auspices of the Arab Image Foundation, I planned a research trip to Mexico in 2003. Initially, the subject of the research was viewed as irrelevant when discussed at the foundation’s general assembly — on the grounds that priority should be given to research within the Arab world itself. I argued that a significant number of Lebanese, Syrians, and Palestinians had been living in Latin America for years — in fact, from the beginning of the twentieth century — and that it would be equally interesting to research the images they had brought with them in their exile as well as any pictures they might have received from those relatives who had stayed behind in their countries of origin. The possibility of studying these images was already compelling enough to build a research mission around. And so my argument was accepted and the trip received the necessary support.

I didn’t know anyone in Mexico and this was to be my first trip to Latin America. I managed to meet most Mexicans of Arab origin by accident. February 9 was a religious event linked to Mar Charbel, a feast that was celebrated in Mexico City with all the fervor that one would celebrate an event that no longer has any meaning except that of providing a link with the mother country. Many Mexicans of Arab descent were present at the ceremony; since they bore names of Arab origin, the job of tracing them was made far easier. While I was expecting to have difficulties trying to convince individuals to part with family pictures — which many regard as their only tangible connection to their countries of origin — they were in fact proud that an institution was showing such an interest in their histories. I told them of the aims of the foundation, explained that we were interested in protecting these pictures from further deterioration, and shared with them our hopes of promoting a project that would encompass diasporas in general, whether in Latin America, Africa, or Australia. To my surprise at the time, I was greeted in Mexico with an enthusiasm and warmth that I have encountered in few other places.

Language was not a problem since I speak fluent Italian and a little Spanish, but some of the people I met made a point of speaking Arabic, although reverted to Spanish within minutes. When I visited families searching for images, I noted down stories of the forefathers of those who gave me the images, including the names of the villages they hailed from. They all told me variations on the same story — their fathers or grandfathers left the Arab region at the end of the nineteenth century or the beginning of the twentieth century for Vera Cruz, on the Mexican coast. Most of them arrived penniless and began selling knick-knacks on foot to local Indians. With time, they migrated to major cities, where they traded in fabrics, manufactured clothes, and opened linen shops. Within years, many became affluent. Most Arab Mexican families live in wealthy neighborhoods of Mexico City. Some are Druze or Jewish, most are Christians, mainly Maronites. They left primarily because of poverty, while emigration accelerated when the Ottoman Empire called upon Christian citizens to serve in the army.

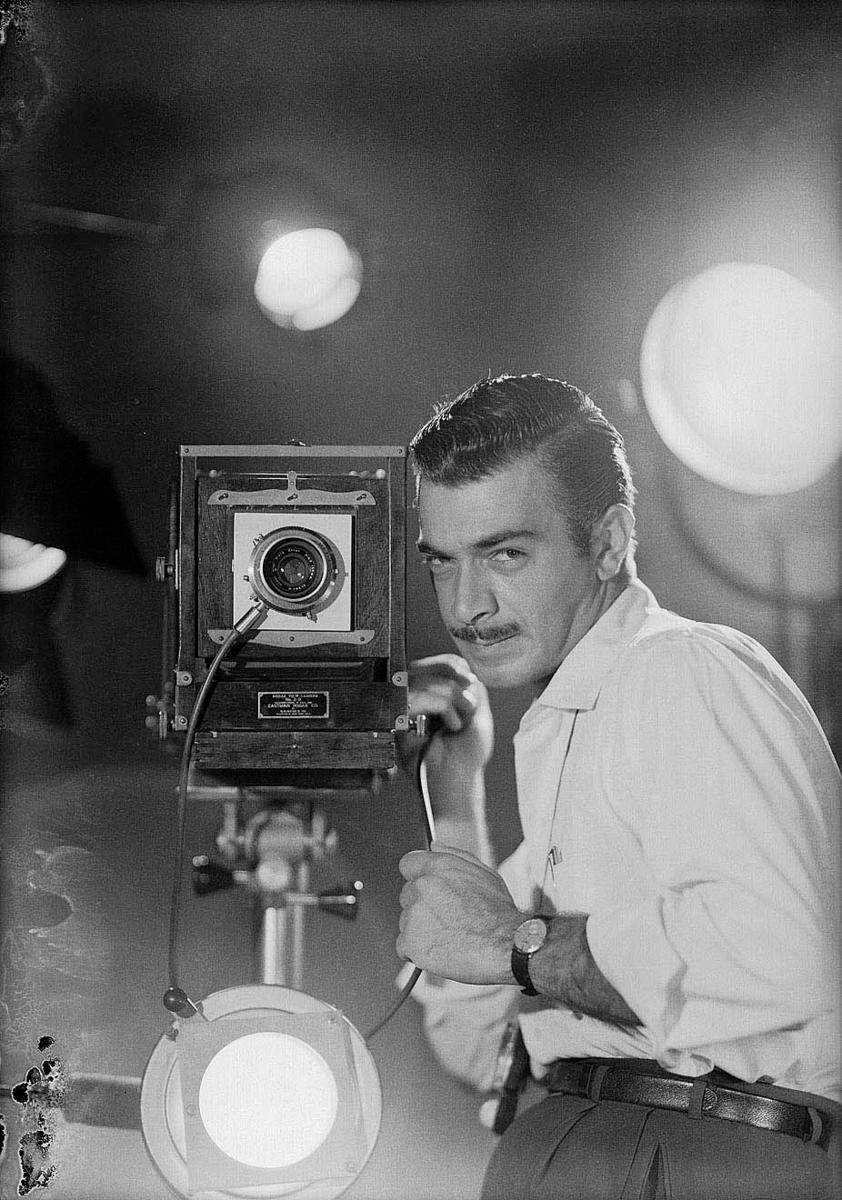

While visiting families, I kept asking for names of photographers within the Arab community. I first went to the Centro de la Imagen, then to the Museo Soumaya, and finally met a woman called Martha Diaz de Kuri, who had published a book on the Lebanese diaspora. Martha gave me the name of Edmundo Feres Yazbek, with whom I would have my most important encounter. He is a photographer, now in his eighties, and, together with his two uncles, Alfredo and Tufic — both of them photographers of Lebanese descent — ran what was called Studio Yazbek. Studio Yazbek was one of the most important portrait studios in Mexico City when it opened in the thirties; concentrating on commercial photography in the fifties, it finally closed in the seventies. Edmundo is now retired, Alfredo and Tufic are dead.

Edmundo received me one evening in his modest Colonia Florida apartment, in the south of Mexico City. Before I had time to sit down in the midst of linen piles, he ran to the kitchen to bring us two cups of coffee (it was eight o’clock at night). Edmundo, who is tall and thin, stood up while I talked about the foundation. Very intimidating, although simple and direct in his manners, he is a seductive gentleman (the following day, when we met again, he took me out for breakfast and walked on the outside of the pavement in a protective gesture). Some of his pictures were hanging on the wall of the sitting room, with one hand-colored portrait of his late wife whom he refused to talk about, as if she had died the day before. He listened carefully to me detailing the aims of the foundation, but when I asked to see more pictures of his, he replied that he had to go to the Lebanese Club nearby. It took me a few visits to try and convince him to collaborate, until one morning, as I was entering his house, he shoved two suitcases full of pictures in front of me.

In them were colored transparencies and black-and-white prints mixed with old family pictures from Lebanon. I was surprised to find them all mixed up in a single suitcase, seemingly unopened for years, as if he had put a lid on his past. Indeed, this was the case. When his studio finally closed in the seventies — because of fierce competition — he stopped taking pictures, save occasionally for the Lebanese Club in exchange for free meals. As I searched through one suitcase, it became clear to me that it was painful for Edmundo to narrate the content of the pictures. Yet there was no bitterness in his attitude; instead he kept repeating that most of the valuable archive of the studio was kept in Tufic’s and Alfredo’s studios, as if he wanted to diminish the value of his own work. I couldn’t understand his reluctance to talk about his work (I understood later that it was somehow linked to the death of his wife), but since I was cautious not to push him, we agreed that he should take me to Tufic’s studio.

We met on a Sunday in the studio where Tufic’s son, also named Tufic, operates. He was extremely happy to have his older cousin around, whom, it seemed, he hadn’t seen for some time. We all gathered in the studio’s warm atmosphere dating back to the sixties, drinking juices that only Mexicans know how to prepare — a mixture of fresh exotic fruits and carrots or sometimes mint. I asked Edmundo to take a portrait of all of us. Within seconds, Edmundo was transformed, the photographer found his marks almost immediately, asking Tufic’s assistant for help to adjust the backdrop and the lighting, climbing on a ladder (at more than eighty years of age) to master his frame. Each time he shot a picture, he would hand the camera to the assistant for him to wind it before shooting again, as he would have done during his glory days.

Above Tufic’s studio was his apartment, where his archives were held, all stacked in files with dates and names. Edmundo stayed with me part of the afternoon looking at his uncle’s pictures, most of the time silent, at times commenting on a series of pictures. Occasionally, he would simply say “this is signed Tufic, but I shot this picture. Tufic never used this setting, he didn’t like it…” The more I stayed with him, the more Edmundo recovered his past, keen on letting more information out. Despite his initial reluctance, I think he saw in the foundation the hope that his work and that of his two uncles might finally receive recognition. He signed a donation contract, and he strongly advised me to get in touch with Alfredo’s son whom I visited a short while later and who, thanks to Edmundo, allowed me to search through his father’s archive.

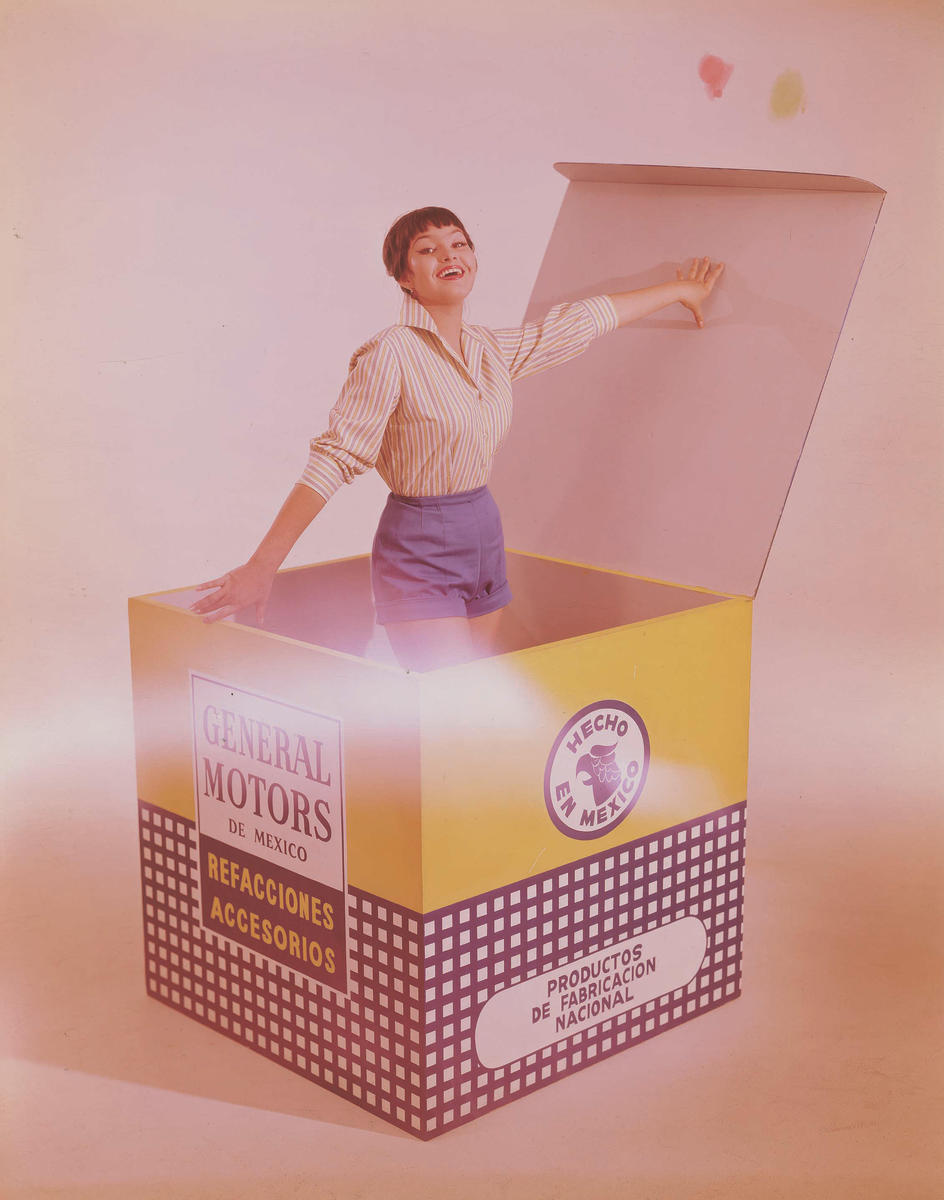

The Yazbek collection provides us with an insight into a certain affluent strain of Mexican society, mostly of Arab origin (many of the portraits I found bear Arab names), while also reflecting what was to become the spreading influence of the multinational, and commercialization at large. From this point of view, there is nothing “Arab” about the collection. But then again, is there anything specifically “Arab” about photography? In the case of Alfredo, who started the business and who, in the eyes of Edmundo, was the reigning master and the most talented artist among them, I took all the available vintage prints and made a selection of negatives dating back to the 1940s and 50s. According to his son, no trace of his series of portraits of military cadets or of Mexican stars was ever found. As for Tufic, who, after training with his elder brother Alfredo, specialized in commercial photography, producing photographic campaigns for Smirnoff, Tecate, Manchester shirts, Disneyland, Coca-Cola and the like, I made a selection of negatives and black-and-white prints. These were brought back to Beirut, scanned and stored, and now await plans for an exhibition.

On the last day of my trip, I came across a stack of old pictures in an open market. I casually looked down at them and fell on one particular hand-colored picture of a Mexican lady. The photographer’s stamp read Saad, Mexico. By all accounts a sign left by another photographer of Arab origin telling me to pursue my research. I bought the picture for ten pesos and moved on.