Editors’ Note

The first entry in this diary of contemporary Iran, “Anger Piled Atop Anger,” provided an intimate portrait of the initial months of the uprising that erupted after the death of a young woman named Jina Mahsa Amini on September 16, 2022. Several hundred people were killed in the cycle of protest and crackdown that followed.

The following entry was written in March of this year, chronicling the dark days of December and January, when the Iranian government began to execute individuals accused of involvement in the protests in the fall. It also captures the new hope that emerged in February, in the days leading up to the annual Revolution Day celebrations.

The Islamic Republic is one of the most enthusiastic practitioners of capital punishment on the planet. In 2022, it executed at least 582 people, up 75 percent from the previous year. The uptick in killing began in May, amid a wave of teacher-led protests, and continued throughout the fall and winter.

It should be said that the execution of Mahsa Amini protesters resumed after a four-month lull on May 19 of this year, with the hanging of three men accused of attacking security officers in the city of Isfahan. As press coverage of Iran dwindles in the international media, we remain committed to circulating documentation of this extraordinary, ongoing, moment in time.

In solidarity, Bidoun

I’ve lost count of the days since Jina’s death and the wave of protests and strikes that followed — a period when something incredible happened every day, when you went to bed each night wondering what might materialize in the streets tomorrow.

By December, the waves of revolt were subsiding and the executions had begun. It seemed like the days of protest were over. The days of grief had arrived.

After the first execution, I spent most of the day at home, staring at the wall. His name was Mohsen Shekari, a young man who worked in a cafe. He was at work when security forces attacked protesters in the street. Mohsen went outside to join them and was arrested for allegedly blocking a street and assaulting a member of the Basij militia with a machete. He was tried in November and found guilty of moharabeh, “war against God” — a capital offense. Mohsen had no illusions about what was going on; he told his fellow prisoners that his sentence was intended to frighten others, to teach them a lesson. They hanged him on December 8. The morning after, a video circulated on TikTok showing a view of the alley where he lived while a woman wailed “Oh, Mohsen,” over and over: his mother, her voice a braid of shock and grief. I’ll never forget the sound.

They killed Mohsen during the morning prayers and announced his death on the news. I hardly slept after that, waking automatically at seven each day to see if they had killed someone else. There were many others like him, detained indefinitely, tortured, railroaded through sham trials and convicted of either moharabeh or efsad-e fel-arz, “corruption on Earth,” another crime that carries the death penalty.

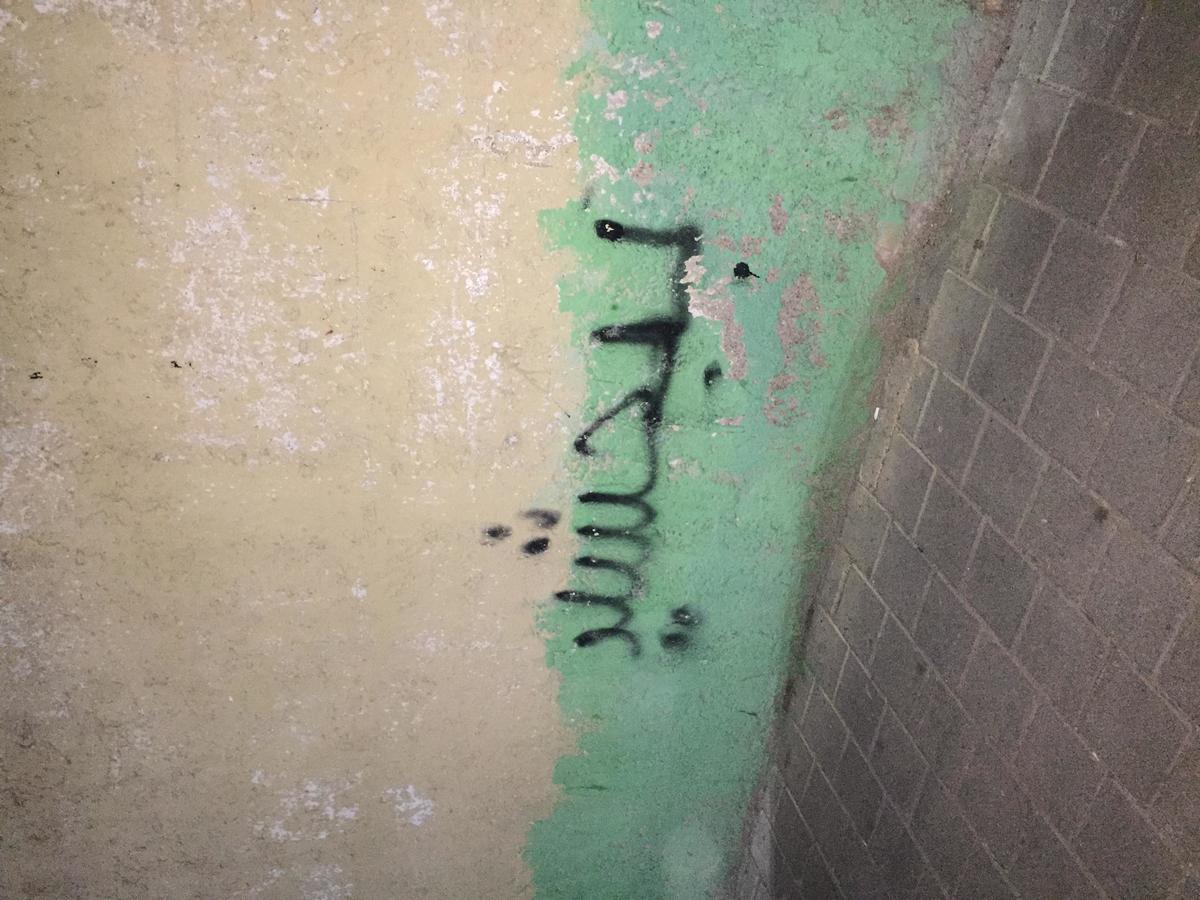

I remember waking up on the morning of December 12, the day they had scheduled the execution of Majid-Reza Rahnavard, 23. There was no mention of him on the news, so I breathed a sigh of relief and went back to sleep. When I got up at ten, it was all over. I saw the images: They’d hanged him from a construction crane, his hands and feet bound, a black bag shrouding his head. Majid-Reza’s body dangled in the predawn dark as crowds gathered round. He had been executed two weeks after his sole court appearance, not even a month after his “crimes.” They said he’d killed two members of the Basij militia during a protest in the city of Mashhad, but the proof they presented to the public was a video of his coerced confession, one arm in a cast, probably broken during a torture session. His interrogator asked him if he had any final requests. “I don’t want people to cry by my grave,” he answered. “I don’t want them to read the Qur’an or pray. I want them to be happy, to play happy music.” He had already been buried by the time his family was informed of his execution. For months afterward, the authorities blocked them from marking his resting place with a headstone. They didn’t want people to lay flowers there.

On January 7, they killed two more. One was a man named Mohammad Hosseini, 39, a poultry worker in Karaj who taught martial arts to kids; he had gone to visit his parents’ graves in the same cemetery where protesters had gathered to observe the 40-day anniversary of the death of Hadis Najafi, killed during the protests in September. Mohammad was accused of participating in the murder of a Basij member. Apparently no one came to visit him in prison. After his execution, his Instagram page circulated. He had guileless eyes, eyes that are etched into my consciousness, but in the photos from his trial, they’d cut his hair to make him look menacing, like a thug.

The other, Mohammad Mahdi Karami, 21, was a handsome young athlete, tried for the same alleged crime. His father, a street vendor who sold tissues to pay for his son’s karate lessons, gave an interview to an Iranian newspaper before the execution, pleading for help to save his son. Everyone knew that the charges were unfair, that the trials had been irregular, that torture had been used to elicit “confessions” that their authors later renounced. Of course, that hardly mattered.

For a while, we thought that the days of grief would never end. The streets of Tehran were empty, and the chants that had rung out from the windows of well-wishers and homebound activists had died down. Kurdistan, long an epicenter of protest, had fallen silent, too. The brave people of Baluchistan were the exception, protesting every week after Friday prayers, a small sign that there was still hope to be had.

But there was another source of hope, of course: All the women going about their business, walking around outside without headscarves. I joined them. Even though it has been an extremely cold winter, I went out every day in a short coat — no headscarf, no hat. One snowy day, a woman, all bundled up, laughed at me from under her big brown hat. “Aren’t you cold?” she shouted. I shouted back, “I have no choice! I can’t cover my hair under any circumstances!” Honestly, I was more than happy to freeze.

One afternoon, I found myself on the outskirts of the city, in a poor neighborhood on the old road to Karaj. I was sitting on a bench to pass the time when a woman in a chador sat beside me. We smiled at each other. A few minutes later, a young woman with a 3- or 4-year-old child and a husband who appeared to be a crack addict joined us. The young woman also wore a chador. As her daughter’s headscarf slid down from her head, she yanked it back up over her hair. The girl laughed, pointing at me. “She doesn’t have a headscarf,” she protested. “Why do you keep pulling mine over my head?” The mother asked me, politely enough, why I chose not to wear a headscarf. “To be free,” I replied. “To be free, so no one can tell me what to wear or not wear. So you can wear your chador, and I can dress like I want.” The little girl laughed again and wondered aloud, “So in the summertime, when it’s warm, will everyone be naked?” To my utter surprise, the older woman in the chador jumped in to protest before I could say anything. “Were people ever naked in the past? Of course not. I didn’t wear a hijab before the Revolution, and I was never naked. After the Revolution, when my daughter applied to university, they interrogated us, so I started wearing a chador. It stuck. But people should dress as they wish.” The little girl’s mother didn’t say a word.

I haven’t worn a headscarf in five months. Even in the most traditional neighborhoods, where I would have expected people to give me dirty looks, I haven’t experienced anything but pleasantness and praise. The other day, a barista at a cafe I like to go to gifted me a pack of cookies with my coffee. “This is for your great style,” he said. I kept the cookies in my pocket for a long time, a symbol of our newly won freedom.

Discussing the events of the past months can be surreal. Something has shifted. Everyone seems to be speaking about a different place, not the Iran we’re accustomed to. The Islamic Republic no longer seems to exist in the same way. We speak of our plans for a free tomorrow as though the Islamic Republic were already dead, its carcass hovering over our heads.

Like the Instagrammers say, “We’re not going back to normal.”

I have to admit: I was never really into Instagram. I’d log on once in a while to post family photos, sometimes to shop. A lot of Iranian home businesses are on the platform, especially women advertising their handmade products. But Instagram mostly struck me as superficial, a playground for influencers collecting likes and money by putting their lives on display. That all changed five months ago. The businesses I followed on Instagram started posting nothing but support for the protests and strikes. On days that a strike was planned, the businesses announced that they would be closed in solidarity. Cafes shut down too. Some went so far as to publish the names of businesses that remained open so that others could boycott them.

Like almost everyone I know, I became preoccupied with these events, posting three or four stories a day about important news, tweets, and analyses. Of course, there was always a danger in posting. Some pages announced that they had been sued by officials for bring attention to strikes. “Don’t forget to delete your archive and chats,” they advised. There was always the risk of getting stopped by police and having your phone searched. It happened all the time. Even to celebrities: In one particularly well-known case, the actress Taraneh Alidoosti was arrested for posting a photo of herself walking down a street without a hijab. No one, it seems, was beyond retaliation. And yet people kept posting anyway.

On Twitter, I was in a relatively unified space among the like-minded people I followed. But on Instagram, I found myself embroiled in debates with distant family members with different viewpoints. For me, this was not a “subversive movement” but a revolution. A revolution that desired neither religious tyranny nor to revert to the tyranny of the prerevolutionary period. (The 1979 Revolution was, in my opinion and that of many others, a case of Iranians standing up for fundamental freedoms, not knowing what awaited them on the other side.) By January, as the streets emptied and people grew increasingly despondent, many had begun to look for a leader to come and rescue them, as Khomeini had in 1979. Into this vacuum stepped the Shah’s son, who has lived in exile for more than four decades. Soon, the royalist television networks and associated Instagram accounts revived their familiar “sweet era of the Shah” nostalgia campaigns, and suddenly, my family WhatsApp group filled up with vitriolic arguments about who had the right to represent Iran and Iranians. Of course, there was a vast divide between those of us at home and the diaspora Iranians.

A surprise boost arrived the first week of February in the form of a bold statement from opposition leader Mir Hossein Mousavi, who ran as a reformist presidential candidate in 2009 and was a key figure in the protests that became known as the Green Revolution. Mousavi, who has been under house arrest for the past twelve years, had always tendered his criticisms from within the framework of the Islamic Republic. Now, he announced, there was no longer any hope for reforming this regime from within. Those days were over.

Then came the photos of Farhad Meysami. An educator and publisher, Meysami had been arrested in 2018 for publicly supporting a series of protests against the very same mandatory-hijab policy. In October 2022, he had gone on a hunger strike; the same week that Mousavi issued his statement, leaked photos of Meysami’s emaciated body, little more than skin and bones, went viral on social media. In one image, he’s holding three books so that we can see the covers: The Narrow Corridor, The Power of the Powerless, and On Tyranny1. These are all books that Meysami translated while in prison. I was haunted by that photograph: the fierce determination in his eyes, the books clutched in his hands like talismans of defiance. In those dark days, it emboldened us.

The Islamic Republic celebrates its founding every year on February 11 — the 22nd of Bahman, in the Iranian calendar — the day the Shah’s armed forces officially surrendered. This year, the billboards that the government placed around the city seemed somehow off: Slogans like Together we rejoiced, together we resisted, together we fought were laid over images of jubilation, resistance, wartime. As some commentators wittily remarked, the whole thing smacked of goodbye. In the runup to the big day, the Supreme Leader announced an amnesty. Prisoners were freed; images of families reunited with loved ones, flowers in hand, were circulated. The regime’s news agencies claimed that tens of thousands were being released; according to one story, a hundred thousand had been pardoned. We were skeptical — how many had been imprisoned in the first place? How could there still be so many political prisoners if a hundred thousand had been released? What inspired the Supreme Leader to suddenly give in? Did they run out of room in the prisons? I still don’t know. It was hard not to be cynical. Yet the news, on February 10, that Farhad Meysami had been released from prison filled us with joy.

The Victory Day celebrations traditionally end with fireworks at 9pm and people shouting “Allah Akbar!” from their rooftops, just as they did during the Revolution. That night, I went to the window. Our house sits across from a mosque, and I could make out some murmurs of “Allah Akbar” through the speakers. The sound made my blood boil. I suppose I wasn’t alone, because within minutes the whole neighborhood was echoing with cries of “Death to the dictator!” Not even the noise from the fireworks could silence us.

With the pardons, the images of freed people clutching bouquets in front of prison doors, and the groundswell of chants against the regime, the movement seemed to be coming alive again. Various organizations, activists, and scholars began to publish lists of demands for tomorrow’s Iran. Reading these texts, however vulnerable to critique and debate, felt like a window onto the dream of the country we desperately want to live in. A country no one wants to run away from, a country that stands for freedom from all forms of tyranny.

It snowed last week, the kind of snow Tehran hasn’t seen in years. S. suggested we go outside and play, so she and her boyfriend and my brother and I filled our metal coffee mugs with homemade vodka and went out in the snow. (The ongoing economic crisis has made the price of foreign liquor exorbitant, so this bootleg Iranian vodka is the only thing we can get our hands on.) We wandered around the snowy streets, drinking and talking about what we would do if this regime really were gone. Simple things, like hanging out at a bar with proper liquor, where we could drink without worrying about going blind. Or like swimming in the neighborhood pool, which they currently keep dry and empty. We spoke of not having to dream about traveling to Turkey to enjoy the simple pleasure of a beach. (That dream is hardly feasible anyway, now, between the inflation and the general state of the country.) We spoke of these little joys and liberties while people who live abroad lectured us on social media, insisting that the only thing that matters is the fight against the mullahs, that thinking about what should come next is unimportant.

Yesterday was the fortieth anniversary of the deaths of Mohammad Mehdi Karami and Mohammad Hosseini. In Tehran and other cities, people came back out onto the streets again, chanting, “Death to the dictator!” as if to say, “Don’t forget us — we’re still here!” Back in September, on the very first day of the protests, my hairdresser had urged me not to go to the demonstrations — it was useless, the regime wasn’t going anywhere. Two days ago, I was back at the hair salon, and this time, he made a point of telling me not to lose hope. “These guys aren’t going to stick around,” he said. “They can’t.”

I smiled.

Translation note: The English version of this text has been adjusted slightly in the editing process and in collaboration with the author.

1. The Narrow Corridor: How Nations Struggle for Liberty, by James A. Robinson and Daron Acemoglu; The Power of the Powerless, by Vaclav Havel; and On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century, by Timothy D. Snyder.