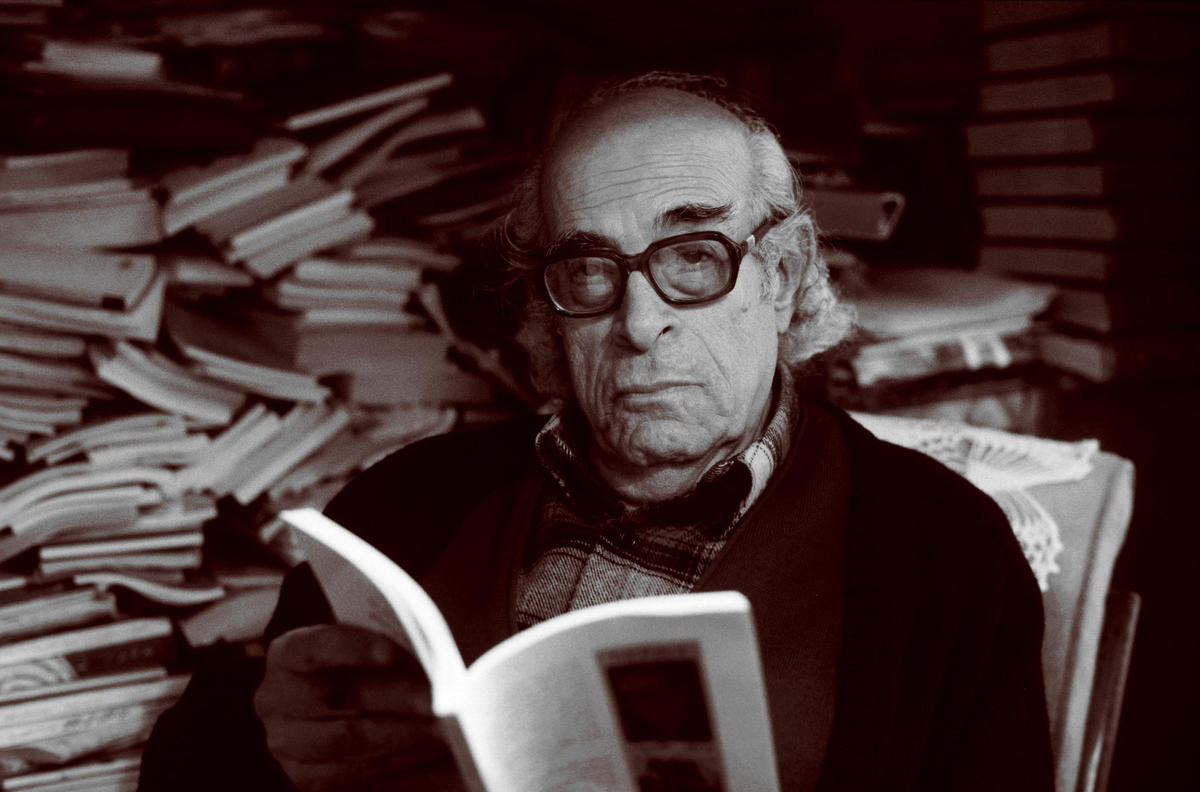

Edwar al-Charrat was born in 1926 in Alexandria, and has lived and worked as an author and critic in Cairo since 1983. One of the most prominent members of Egypt’s literary scene, he has received several awards, including the Naguib Mahfouz award from the American University in Cairo in 1999. His novels, including_ Rama and the Dragon (Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 2002), City of Saffron (London and New York: Quarter Books, 1989) and Girls of Alexandria _(London and New York: Quarter Books, 1993) have been translated into several languages.

Bidoun: You’re one of the very few established writers interested in the young writers’ scene. What in your opinion is the most interesting current development here?

Edwar al-Charrat: It’s what I call ‘trans-generative writing.’ Normally writing is classified into genres, but I don’t believe that literature can be put into these pigeonholes. I believe instead in experimental developments, in collaboration between areas such as poetry, cinema, theater, or the plastic arts. Writing that does not stick to the boundaries of particular genres — poetry as such, the novel as such.

Bidoun: What is the situation like for young writers in Egypt today?

EaC: Compared with how things were in the past, it is easy to get your text published. Today, we have quite a number of different publishing houses that are happy to publish whatever young writers give them. To the point that they often choose without much care.

Bidoun: Is there anything similar to what we’re seeing with the development of hyped, so-called ‘pop writers’ in Europe?

EaC: No, not really, because the principle here is to encourage young writers from the provinces. And besides that, the trend has not gained much awareness. But it is an open gate — so open that these writers have no difficulty getting their works published.

Bidoun: What kind of dialogue is there between established and emerging writers? Is there any exchange?

EaC: In a way yes, and in a way no. There are groups of authors such as the ‘Atelier of Cairo’ or the ‘Atelier of Alexandria,’ which regularly organize readings, book reviews, and book presentations. But some of the established writers do not really care about young writers or others, and that includes the young — whether that’s because of professional jealousy or professional illness… [laughing]

Bidoun: What about the distribution of literature in the Arab world in general?

EaC: There are problems concerning prices, import and export regulations, censorship — all sorts of problems, so it is very difficult to have a novel distributed throughout the Arab world. We still have a situation where it is much easier to publish in England or France than in Morocco or Lebanon. Exchange is difficult. The only breakthroughs come during the book fairs.

Bidoun: What are your thoughts on this year’s Frankfurt Book Fair? It has been said that quite a number of writers refused the invitation from the Arab League, due to the fact that they oppose their policy in general. Has the whole thing become a political issue?

EaC: Well, some of them did refuse, yes, but as far as I know 200 qualified writers from Arab countries invited by the Arab League will be coming. Of course this is not the complete picture, but politics may be unavoidable. There are people who have not been invited for several reasons. This is especially true of young writers. If they are not at the book fair, at least their books will be, as some publishing houses have translated them. So their work will be there even if they themselves are not. It is a pity because it could have been a chance for the younger generation. But sometimes too much publicity can reduce creativity. So perhaps it is not for the worse.

Bidoun: Translation is always a big issue, especially when it comes to literature. Do you feel well represented by your translated books?

EaC: I’ve been lucky with my translations. But in general, I believe that translation should not be a one-person task. The best strategy is to have an Arabophone and an Anglophone working together. Honestly, I think translation is what I may call ‘creative betrayal.’

Bidoun: Back to the language. How do you handle the different approaches of fussha and ‘amiya in literature?

EaC: The boundaries between fussha and dialect have been slowly eroding for a long time — for example there are classical writers like Ibrahim Abdelkadr al-Majd, who used fussha syntax and mingled it with dialect words to give a richer variety to the writing. They do not even hesitate to use dialect words that are not accepted by old lexicons or dictionaries. The interaction between the two languages — or I would even say dialects — is possible. Because in the end, what is fussha? Fussha is a dialect spoken by a tribe in Saudi Arabia, the Qurash. And because of the Qur’an this particular dialect has been established as the purest form of Arabic.

Isn’t there a kind of reluctance to change this?

You cannot change it, because it is based on the Qur’an. But what is developing is a fusion between fussha and dialect. I am not talking about introducing dialect when writing dialogues — I am talking about using dialect in narrative text. In my books you will find this. I try not to lose the dialect in making it fussha, because fussha does not have the richness and the flavor that dialect offers you. In the end, it depends on the talent of the author — whether you manage to use the richness or not.

Bidoun: Are there any young writers whose work you would particularly recommend?

EaC: The issue is a sensitive one. But let us try to mention the outstanding young writers in Egypt. If I forget somebody, let them forgive me.

One of them is definitely Montassar al-Qaffash. He already has two or three good and promising books to his credit. He writes short stories and novels, the latest one being Tasrih bi-al-ghayab (Permission for Leave of Absence). What is characteristic of his writing is, first of all, the absence of high-flown language, the lack of metaphors and symbolism. He doesn’t rely on day-to-day realism, but hints at situations that lie beyond the obvious.

Another representative of this form of writing, who is also promising and good in his field is Mustafa Zikri. He is a screenplay and scenario writer and gained quite a lot of attention with his latest film Afarit Al-Asfalt (Demons of the Asphalt). Besides that he has written at least two important books, one of which is Huraa’ Mataha Qutiya (Drivel about a Gothic Labyrinth). Without using high-flown or metaphorical language he resorts to the outrage of fantasy, mingling reality with the imaginary in a way that is truly captivating. For example, he uses themes from the Arabian Nights — Alf leil wa Leila — but introduces these themes into everyday life. It is not the depiction of reality as a common phenomenon that grabs you, but the mingling of the inner and the outer, the spiritual and the material, the fantastic and the down-to-earth. It’s possible to compare his writing with comic strips – although comics have an abstract, graphic characteristic and therefore tend to lack the ‘warm blood’ that made Demons of the Asphalt so special.

Another example from this generation is Haytham El-Wardany, who writes short stories that also shift between realism and fantasy. His latest publication, Jama’at Al-Adab Al-Naqis (The League of Incomplete Literature), shows a range of approaches to the art of short-story writing — from dry reportage to formal experimentation — in a very easy and sometimes ironic way.

A fourth writer, who is also very interesting, but with a totally different approach, is Kheiri Abdelgawad. He deals very courageously with the folkloric and traditional side, but in a different way from Mustafa Zikri. Abdelgawad uses the Arabian Nights, as well as the tales of itinerant storytellers. He uses the techniques and the style of the popular narrators and popular poets of the coffee shops, where the old poets used to recite and receive the tunes of simple and primitive music and intoned verses in dialect. He uses this in a very ingenious way to introduce a metaphysical quest. Through his writing he is looking for answers to questions such as who we are, what the meaning of love is and what of death. These high themes, treated in a folkloric way, produce a certain meaning that is absolutely new and interesting.

Edwar al-Charrat’s recommended reading

Montassar al Qaffash

Tasrih bi-al-ghayab (Permission for Leave of Absence), Cairo: Dar Sharqiyat lil-Nashr wa-al-Tawzi, 1996

An Tara Alaan (To See Now), Cairo: Dar Sharqiyat lil-Nashr wa-al-Tawzi, 2002. German translation (by Ola Abd el-Gawad) to be published late 2004 by Lisan Verlag, Basle

Haytham El-Wardany

Jamaat Al-Adab Al-Naqis (The League of Incomplete Literature), Cairo: Miret for Publication and Information, 2003.

Mustafa Zikri

Al-Khawf Ya’kul Al-Ruh (Fear Eats the Soul), Cairo: Dar Sharqiyat lil-Nashr wa-al-Tawzi, 1998

Hara’ Mataha qutiyya (Drivel about a Gothic Labyrinth German translation to be published October 2004

Afarit Al-Asfalt (Demons of the Asphalt), screenplay, 2003

Kheiri Abdelgawad

Al Hakayat al-Dib Rama’a (The Stories of Ramathe wolf)