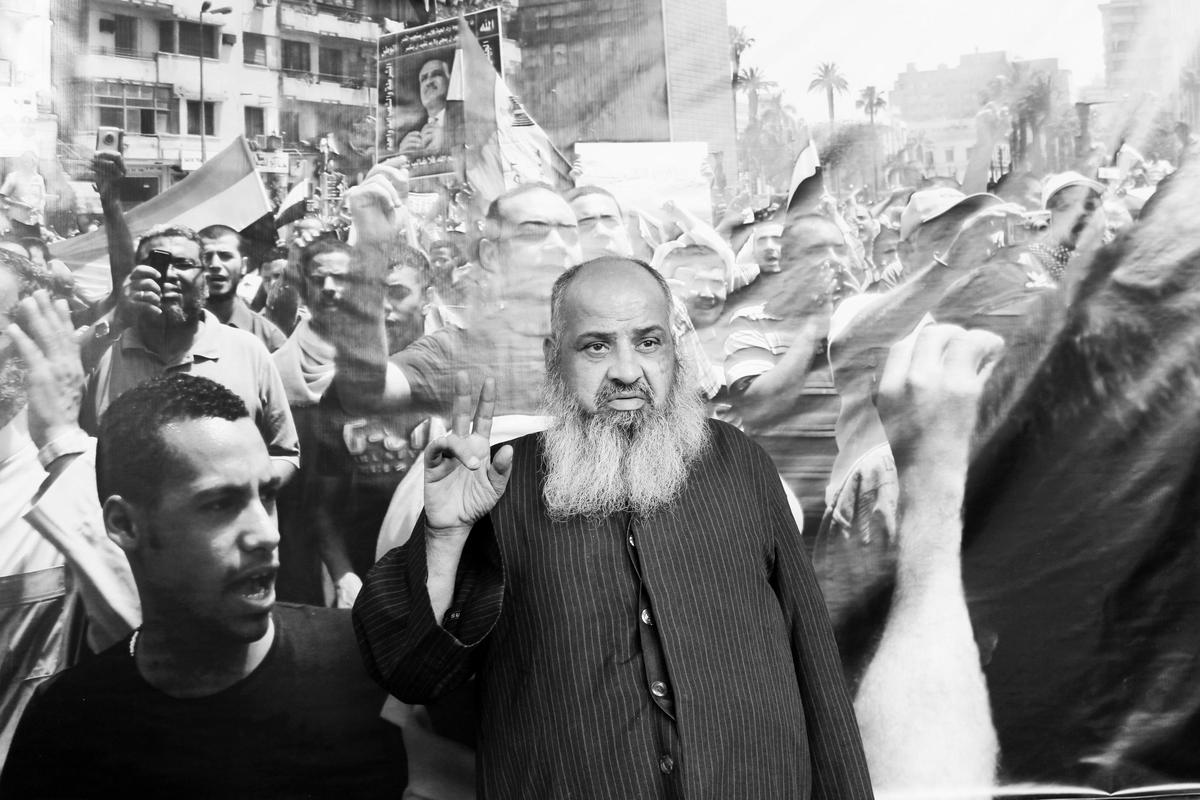

Abdel-Halim Qandil is a prolific journalist and editor whose work has been censored or banned many times in the past decade. He is currently the editor of Sawt Al Umma (Voice of the Nation). He was a founder of Kefaya (Enough), the Egyptian Movement for Change, as well as its official spokesman from 2004 to 2007.

Bidoun: You wrote three books about the Mubaraks that were banned. Can you tell us about them?

Abdel-Halim Qandil: Actually, there were four books:

Did El Rayis (Against the President), 2005.

El Ayam El Akhira (The Last Days), 2008.

Cart Ahmar lil Rayis (Red Card for the President), 2009.

Al Rayis El Badil (The Alternative President), 2010.

Did El Rayis was printed after I was kidnapped by the regime’s security agents. After beating me, they threw me into the middle of the desert, naked. This was inspired by the articles I wrote, which represent the longest, biggest campaign against the president of Egypt and his family in the history of the country. My campaign against the institution of the presidency began on July 18, 2000, just after the passing of Hafez El Assad in Syria. The Syrian parliament met to conspire; the age for presidential candidates was reduced; and so, Bashar El Assad became president, replacing his father. Now remember, that same year Gamal Mubarak was in a similar position in the ruling National Democractic Party in this country. That book was published by Dar Merit. It is the least famous of my four books.

El Ayam El Akhira was based on the premise that we were experiencing the last days of Mubarak and posed the question: What will the end look like? It proposed five scenarios. One scenario was “The Impossible Succession.” It was more or less about Gamal Mubarak coming to power.

The second scenario was in fact a peaceful protest and sit-in in Tahrir Square. This was based on my belief that Egypt contained enough rage to make a thousand revolutions, but this rage had seeped into the ground, collected into what had become a tomb of rage, and it would required the lifting of its lid. [Draws circles and lines to illustrate the ground, tomb, and rage seeping under the ground] I imagined that this would take a hundred thousand citizens — that would be enough to lift this lid and release the rage of millions. And my focus was on Tahrir Square, where these millions would congregate.

The other scenarios included “A Nation Combusts” — a security vacuum, sectarian strife, general civil chaos and disorder. “If the Military Ruled the Country.” And “If the Muslim Brotherhood Ruled the Country.” I imagined that these last three scenarios would come into play at the moment of Mubarak’s departure, whether through death or the kind of peaceful uprising in Tahrir I suggested in scenario two.

El Ayam El Akhira was published in difficult circumstances. The writer Sonallah Ibrahim endorsed the book, and, as you know, he has long held a position against the regime, going so far as to refuse a top literary prize from the state — saying he could not receive a prize from a dictatorial system. After my book was published, Sonallah received a statement from the military calling for the immediate halt of its distribution. This was a problem at the time, because there was a party for the book at the journalists syndicate, which I belonged to. On the day of the party, there was a security takeover of the premises, and they halted the party. There was an exceptional turnout, almost three thousand intellectuals and artists and writers, so it was a big embarrassment, a catastrophe, for the regime.

After the launch, El Ayam El Akhira became widely distributed as a secret publication. I mean, I am the inventor of the book, but this book, both before the revolution and after it, has been printed hundreds, thousands of times without my knowledge. Everyone photocopies or prints it and then distributes it. If you look at the market, you will find that everyone has cooked up a different price for it. It has nothing to do with me anymore. You could say I consider this book the nation’s property — it belongs to the people.

And you know, the covers of these books — all of them — were used as posters in Tahrir Square during the revolution.

In Cart Ahmar lil Rayis, the main idea was, How do we get rid of Mubarak? The premise of the book is that Mubarak’s rule is unlawful, even against sharia, so the endeavor to get rid of him is a lawful endeavor. The book examines the use of the street for this task of annihilating the president, to whom I give a red card, or a foul, like in football. Hence the title.

The book makes a case study of the workers’ uprising on April 6, 2008, in the city of Mahalla. It suggests that it would take just five similar uprisings, in five cities simultaneously, to cause a national revolution to remove the president. Mahalla times five would bring success. The president would be removed. We could do it.

Al Rayis El Badil is about who would come if the president were removed. In this book, there is a general. And it is not necessarily Omar Suleiman. You have to understand, the military was against Gamal Mubarak, but they were absolutely and perfectly fine with accepting Hosni Mubarak until the day he went to his grave.

In this book, I spoke of the last elections, which were the greatest fraud in the history of the nation, maybe any nation, maybe the world. The book was published in 2010, yet it spoke of the elections as if they were the final elections this regime would see. It was written with the understanding that we were approaching the end. I had a sense we were moving toward a transition period and a period of rule of the generals. I had a sense of this eruption at the end of 2010…

Bidoun: Why did you know and no one else?

AHQ: Trying to get rid of Mubarak is a journey of at least ten years… I’ve worked for many newspapers, from Al Raya in Qatar to El Araby to Al Karama and now Sawt Al Umma. I published four books. I was completely banned from writing for two years, from March 2009 until the revolution — there was no written decision, but the ban was upheld by intimidation and threats, both to me and to the people who published me. It’s been ten years of fighting against the regime, predicting its end. When I started this campaign against Mubarak, everyone looked at me like I was crazy. Now they think I am a prophet. The truth is I am neither. What I saw is different from what the rest of the country saw. What I see, I see differently.

There was a time years ago, I think it was 2003, when Mubarak was addressing parliament and suddenly the reception on the TV was cut. Some long minutes later, the Minister of Health announced that Mubarak had a terrible flu. There was much talk about the succession issue in light of the frail nature of his health. Where the people saw just a leader, I saw an entire regime as weak, as sick. A corrupt family with billionaires around it that relied on a dense security apparatus. To me, the regime had died long ago; it was just overdue for its burial.

You can say that the regime had destroyed everything, and what resulted was the suffocation of the people, pushed into the underground grave I spoke of. The only thing that these people needed was a critical mass to raise the lid off this tomb of rage. And the regime itself, I believed, would help with the lifting of that lid, because any opposition to the regime was immediately crushed with the security apparatus and torture. So if you return to my scenario, if uprisings like Mahalla took place, and if you could envision the security apparatus pushing back, it creates tension, and provokes the people to react. And eventually, provoked by the state’s own apparatus, the hundred thousand people necessary to make a revolution would come together.

B: What changes have you noticed in publishing since the revolution?

AHQ: Well, look, today’s newspaper has reprinted a piece I wrote from 2008 called “Red Card” that was previously banned. So there is change.

Still, quality has been affected. People can write whatever they want… it is spiraling out of control. The same people who staunchly defended Mubarak are now attacking him. This I see as the greatest problem.

We need a social cleansing and a cleansing of the media! For example, people like Osama Saraya at Al-Ahram — who first denied the revolution was happening, then said the youth were causing chaos and disruption — now say the revolution is beautiful! Remember, after the Tunisian revolution, Abdel Moneim Said wrote that it would be impossible for such a thing to happen in Egypt. He should be ashamed. Embarrassed. If I were in his place, I would resign.

On February 2, Al-Ahram came out with the headline MILLIONS COME OUT TO SUPPORT MUBARAK!

On February 11, it came out with the headline THE PEOPLE OVERTHROW THE SYSTEM!

All those who were part of the regime’s media operations should step down. The people who were most scared to speak are now coming out and saying what they want. The Muslim Brotherhood were too scared to use Mubarak’s name. Now they have no problem doing so. Everyone is a hypocrite. All the hypocrites should stop writing immediately.

There is devastation in intellectual life, though there are some people with integrity — Ebrahim Eissa, Alaa El Aswany, Fahmy Howeidy. They are not necessarily for the revolution, but they have always been against the regime. They are not swayed as power sways.

B: Can you dictate the process of cleansing you speak of?

AHQ: First thing, cleanse anyone who was involved with the old regime. They played more of a role in the system than the interior ministry ever did.

Secondly, we need clear principles for the profession. This is divided into three parts: One, we must ensure the independence of the journalists. Two, there are twenty-five articles in the law that can land editors in jail — for example, article 179, slandering the president — which need to be reformed. Three, there also needs to be some law or legal measure that ensures that journalists will be able to get information from official entities when they request it.

Third, there is the question of ownership and legal licensing. All state TV should be canceled and there should be a channel modeled after the BBC, a general public channel. All these publications, like Al-Ahram, need to be restructured so they are not the voices of the regime. And the ones losing money, like Rose Al Youssef, should be canceled.

B: Are we experiencing a moment of total freedom?

AHQ: There is freedom, but it is temporary… it could end any minute.

B: Are you happy?

AHQ: Yes. But there is still great insecurity. We have paid the price for Mubarak twice. Once when he was here, and once again now that he is not.