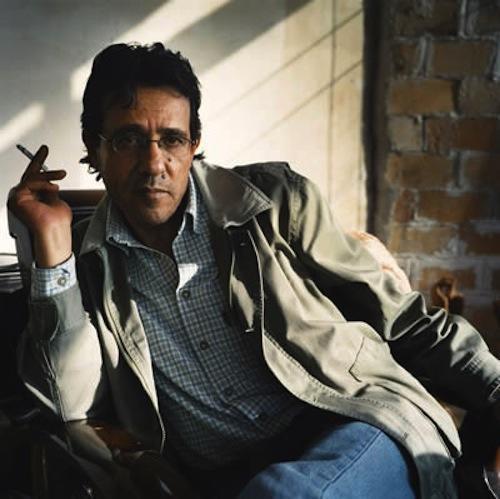

Ghassan Zaqtan was born in 1954 in Beit Jala, near Bethlehem. Co-founder and director of the House of Poetry in Ramallah, he is chief editor of Al-Shua’ra (Poets), a quarterly magazine, and writes weekly columns for two newspapers in Ramallah and the Gulf. His own poetry collections include Luring the Mountain in Beirut (1999); Prescription of a Description in Jerusalem (1998), and Weightless Sky (1980). His novel, Describing the Past, was published in Jordan in 1995. Ghassan Zaqtan has also written a number of scripts for various film documentaries, among which his screenplay The Narrow Sea was honored at the 1994 Cairo Festival.

Bidoun: Could you tell us a bit about the young literary scene in Palestine?

Ghassan Zaqtan: I think we have quite a new movement. We are talking about writers who are under thirty-five — both poets and writers of prose. The movement is even stronger in poetry than it is in prose.

Bidoun: Why do you think young writers are more interested in poetry?

GZ: Because it is an easier genre to start with. Most of these writers will change later to prose. In regards to Palestine, I’m speaking from my experience as the cultural editor of Al Ayam.

Bidoun: Can you characterize the young writers you’re referring to?

GZ: The most significant characteristic is that their art has liberated itself from the chain of the political cause. They do not have to gain their legitimacy through serving the cause anymore. Instead, they simply try to be more themselves. They are questioning the situation as such and the human being, which is not new, but has not been the main movement of Palestinian poets in the past. Most of them choose themes from daily life — from macrocosms to microcosms. We had three main subjects around which our culture used to circulate: the hero, Palestine as a promised land, and the chosen people. Let’s take the hero to make it clearer. The hero is a holy character in the Arab and Palestinian tradition and we always try to protect him. Of course at the end, we send him to die. He has to be dead to be fully heroic. The young writers have smashed the hero totally. They do not care about the old style of heroes anymore, and try instead to create another kind who is very human. The new generation is abandoning these subjects and replacing them with everyday realities — not only in poetry, but also in prose.

Bidoun: Have there been any recent changes in style or structure?

GZ: When you change the subject, when you choose ‘inner subjects,’ you have to change your language as well. You need a new language. But the new writers get their inspiration from the allied disciplines of cinema and the plastic arts. Their sentences become shorter and sharper, the language is closer to street language. For example, when you compare the old texts with the new ones you discover different layers and colors that have not been used in this way before. Their texts seem to encompass the full range of senses. Perhaps it is not possible to speak about a clear direction, but we can definitely talk about new voices.

Bidoun: Can you give us some names?

GZ: In poetry I would focus on Walid Asheikh from Bethlehem, Tariq El Karmi from Tulkarem, and Bahsir Shalash, from inside the green line. For short stories you could name Hatif Abulzeid, Akram Abusallah, Adania Shibli, and Alaa Hlehel. Alaa is special because he has a very particular voice. He may not like this, but in my opinion he can be compared with Emil Habibi, who played an important role as a Palestinian in Israel and is one of our greatest novelists. Habibi’s The Secret Life of Saeed has been translated into thirty-five languages and, controversially, won the Israeli literature prize in 1992; despite pressure to refuse it, Habibi said that it was a victory for the Palestinian cultural movement, and accepted the prize.

This new generation has another big advantage over us, the older and established one. Not only are their readers of the same age, but so too are their critics, which is very important for the whole movement. Among them are Malik El Rimawi and Abdelrahim As-Sheif. That’s what makes them more complete than our generation of writers. At first, we tried to avoid or escape all these inner subjects. Our generation took its first steps in that direction after the Beirut siege of 1982, because the political movement lost its power. We started to question the system and jumped beyond political programs. But all our critics belonged to the previous generation, which had no connection to our writing. It’s impossible to develop without productive criticism.

www.pal-poetry.gov.ps

Ghassan Zaqtan’s recommended reading

Adania Shibli

Masas (Senses), Beirut: Dar Al Adab, 2002 (recently published in French by Editions Actes-Sud)

Kulluna ba’eed bidhaat al-miqdaar ‘an al-hubb (We Are All Equally Far From Love), Beirut: Dar Al Adab, 2004

Ala Hlehel

A-serk (The Circus), Beirut: Dar Al-Adab, 2001

Kisas le-Awkat al Tajah (Stories at the Time of Need), a collection of short stories, Beirut: Dar Al-Adab, 2003

Atef Abu Saif

Mu ’assasa filastinîya li-l-irshâd al-qaumî (Bitter Fruit of Paradise), Ramallah: Palestinian Institute for National Guidance, 2003

Walid Asheikh

Hietho la shajar (Where There Are No Trees), a poetry anthology, Ramallah: House of Poetry, 2003

Emile Habibi

The Secret Life of Saeed: The Ill-fated Pessoptimist (translation by SK Jayyusi, T Legassick, Salma Khadra Jayyusi), and Trevor Le Gassick, London: Zed Books, 1985