In 2006, the Qatari-funded Arabic news station Al Jazeera spawned an English-speaking sister-channel, Al Jazeera English. I’d urge you to find a way to watch it. Unlike almost every other news channel I can think of, AJE doesn’t have a single, nationally biased outlook. It’s polycentric — mirroring the way in which the twenty-first century is increasingly a collection of separate and yet connected economic, political, and cultural centers.

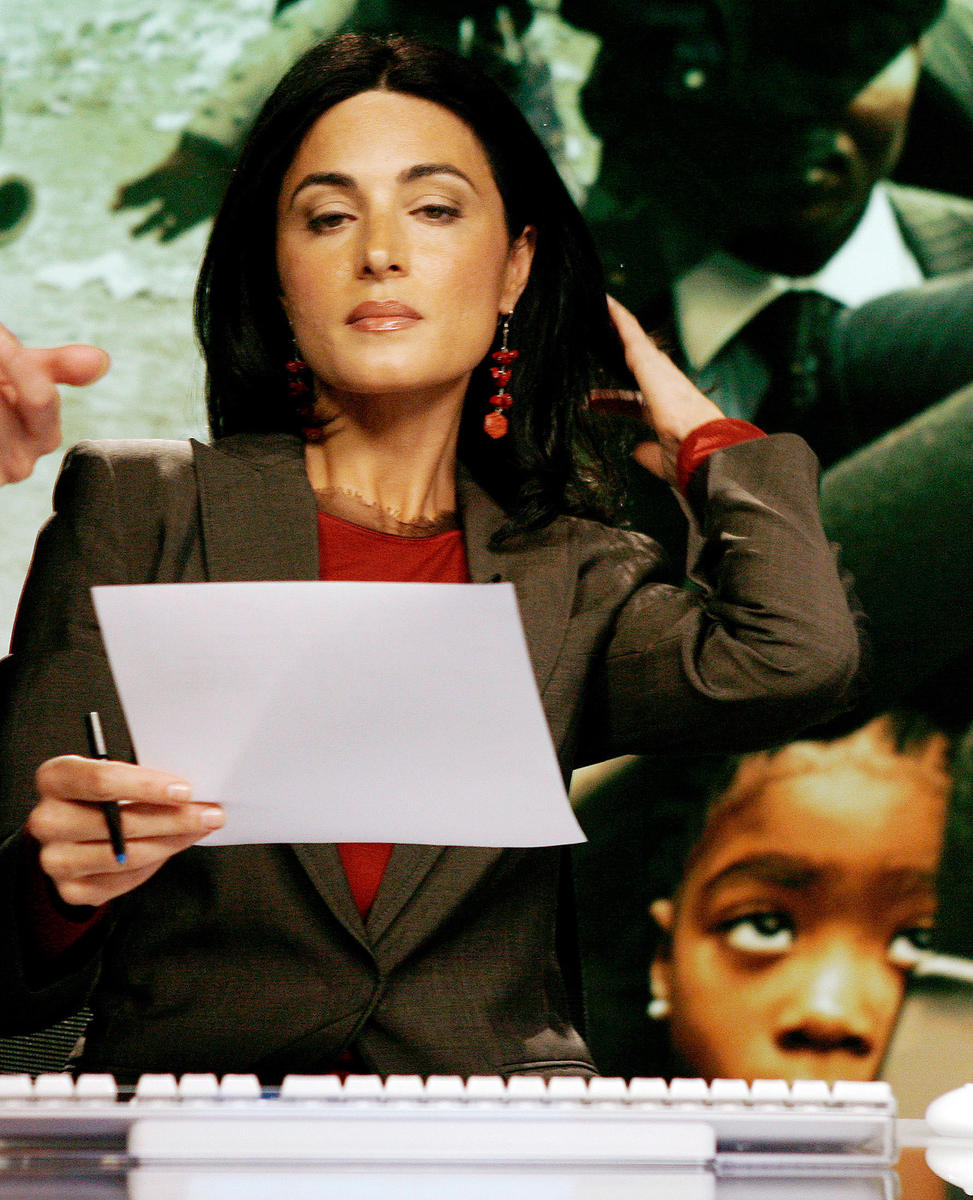

When you do switch on AJE, one of the faces you will find co-anchoring the Washington broadcasts is the Lebanese-born, British-Swiss–educated Ghida Fakhry. Like many of her colleagues on AJE, Fakhry knows her stuff — in particular, the intricacies and histories of Middle Eastern conflicts, her passion. This might grate on those chauvinistic media dinosaurs — brilliantly parodied in the Will Ferrell comedy Anchorman — who would try to use Fakhry’s looks to undermine her seriousness. A self-described news junkie, Fakhry’s got more important things to think about, and she discusses some of them here on her weekly day off, unable to avert her eyes from the TV news quietly streaming in the background as we speak.

Shumon Basar: Ghida, I’ve recently been rereading a book called The Gulf War Did Not Take Place by Jean Baudrillard, which as you know is a kind of provocative thesis about the mediatization of the first Gulf War. He makes the infamous claim that war on television becomes almost indistinguishable from other types of TV entertainment. I remember watching CNN at the time. The green veil of night vision did make it seem like a war movie. Something was very new about the experience. You said once that it was the coverage of the Gulf War that inspired you to become a journalist. Could you tell us more about this personal realization and what it was about the first Gulf War coverage that affected you at that time?

Ghida Fakhry: Seeing in real time what was going on in the region was so dramatic and had such far-reaching consequences. All that night vision, all the new technological tools, they were quite extraordinary. It was the first war to reach our living rooms on a nightly basis. I remember sitting there writing my master’s thesis and realizing how much time I was spending stuck to the TV watching what was going on. I was studying the history of politics in the Middle East, starting from the First World War onward. So, for me, it was an important realization about how powerful the media was becoming, and that immediate, real-time TV was going to be a force to be reckoned with. As an aspiring journalist, and someone who had always admired the field, I decided this would become what I would focus on. I wanted to combine my keen interest for this medium and my realization of how important it was going to be, with wanting to learn more about the region that I had come from. I had been born in Lebanon, and left when I was young. Suddenly I wanted to learn much more about what was going on in the Middle East.

SB: What was your master’s thesis on?

GF: It was on the period of the Independence of Lebanon, the role that the British had played. I was doing my master’s in London at the School of Oriental and African Studies, and I had easy access to some of the archives over at St. Antony’s College in Oxford. It was interesting to see all of the influences that affected modern Lebanon.

SB: CNN was the news channel responsible for the new kind of news reporting during the first Gulf War, and the station has long been acknowledged as a revolutionary force in changing how we perceive and consume news on TV. I believe that Al Jazeera English is also a radically new model. Over the course of the broadcast day, as the earth turns, the station broadcasts from four different cities — Kuala Lumpur, Doha, London, and Washington — and moves seamlessly from East to West. Could you say something about this polycentric model and the kind of world image it produces?

GF: As much as CNN was pioneering in bringing this kind of twenty-four-hour news model, I think Al Jazeera Arabic and Al Jazeera English play an equally important role, by providing an alternative perspective. It’s a network that fills an important vacuum in international news, bringing to the fore cultures that have often been neglected. It also brings new voices to the debates on key international events, and it doesn’t shy away from asking the tough questions when it covers each and every conflict. The whole point is that it doesn’t believe in sanitizing the news, so when a war is going on in the world, it’s the duty of broadcasters to not just show the images we saw in the first Gulf War — those sort of grainy, green images that seemed like fireworks, that seemed almost unreal, just lights in the sky. What we saw was completely abstract. We had no concept of what the effect of the bombs was on the other side, on where they were landing. We didn’t see the effect on people, we didn’t see the death and destruction.

SB: I would like to talk about war more specifically in a moment, but can I push you further on this question of broadcasting the news from different “broadcast centers”? What are the effects of this, and what kind of world does it represent?

GF: I think it actually represents the kind of world we live in. To date, the media, especially the English-speaking media, has always had a Western-centric look at the world. So much of the developing world, the south in particular, had been ignored. What you’ve got here is from its inception a very ambitious project: a network based in the Middle East, addressing an English-speaking audience, but also coming out of four different hubs, in high-definition quality. It’s a big effort from a technological perspective, but also from an editorial point of view.

Each broadcast center is able to give a more authoritative treatment of what is going on in its own region, as well as looking at the news of the day from a regional perspective. So when we broadcast from Kuala Lumpur, we find that a lot of the news stories being treated in depth have to do with the Asian region. London is the European broadcast center, so even if Doha is leading the News Hour, our flagship show, London will be the one to deal with all the European stories, and here in Washington we put our own touch on what’s going on in our part of the world. I think this shows that Al Jazeera isn’t being driven by any single agenda. In fact, I think its whole agenda is not to have one.

SB: For several years after 9/11, Al Jazeera was taboo in the US. It was assumed to be a pro-jihadist mouthpiece for anti-American sentiment. Do you think this taboo has subsided? Have you been accepted by the American political mainstream?

GF: I think it’s starting to change. Obviously the network was stigmatized for many years by the Bush administration. The kind of coverage that was coming out of Al Jazeera didn’t fit, perhaps, the official rhetoric that was coming out of the White House, the Pentagon, the State Department, on how the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were going. Now we have some breakthroughs here in the US, with a new cable carriage agreement in the Washington, DC, area, which means American viewers are able to, for the first time, just switch on their TV sets and watch us. In July the channel will be seen in twenty states live, twenty-four hours a day. So that’s a big development, even though it’s a first initial step and it took quite a while for us to get there.

I think the posture of the new US administration is very different from the previous one, and that will probably encourage more carriers to broadcast the network. When people see it for themselves, they are often surprised, because what they see is certainly not what they had been led to believe all these years. But I think after eight years of Bush administration rhetoric, people are more eager to listen and engage in debate and also more critical than they used to be, less gullible, and more willing to challenge centers of power and authority. And that’s exactly what Al Jazeera stands for. Even though there’s been no fundamental shift here yet, there are little telltale signs that things are beginning to change. One of our senior correspondents was part of the press corps that accompanied President Obama on his last trip to Europe and the Middle East. I don’t think that would have happened under President Bush.

SB: Though I had known about Al Jazeera English, I hadn’t actually tuned in to it until relatively recently, during the Gaza War. The channel was clearly exceptional, because it was the only station that had correspondents inside Gaza. It was the only station giving airtime to everyone involved in the conflict, including Israeli press officers and Hamas leaders. What were the particular challenges of covering this conflict? Was there anything new about it, from a news-culture perspective?

GF: It’s interesting that you say that Al Jazeera English was brought to your attention during the Gaza conflict. I think a lot of people would share that view. Many people started watching us because there was a scarcity in coverage on the other networks. The networks that are readily available tend to focus on what they think their audiences want to see. They tend to cater to a more local audience, I think. In this case, we thought it was our duty to show what no one else was showing to a global audience. We were also in a unique position.

We didn’t have a team that was parachuted in the day before, we were stationed there — our team had been reporting from there for a while. We had been showing the world what was going on in Gaza before so many new viewers began to tune in. It’s at times of crisis that people tune in to twenty-four-hour news channels like Al Jazeera. We were able to fill that void quite well.

SB: Many wars are fought, of course, simultaneously with those literally unfolding on the ground. Many commentators said that the Israeli press machinery mounted a concerted effort to win the news war this time around, and in my opinion the BBC discredited itself, not fulfilling its obligation for balanced, decisive reporting. It wasn’t vigilant enough in the war that’s fought at the level of press releases, claims, and counterclaims.

GF: I think you are right, crises like the one that unfolded over twenty-three days in Gaza just show you to what extent the media has a crucial role to play. So what you saw was a well-oiled Israeli PR machine. Israeli officials were given ample time on Al Jazeera to make their case. The network gave them the airtime in order to explain all sides of the story. At the same time, we knew we needed to challenge the official narrative, whether that meant the Israeli spokespeople we had on or the spokespeople for Hamas, while still being fair to both sides and allowing the viewers to come to their own conclusions.

I think what I was particularly proud of in our coverage of the war in Gaza was that we were the first major TV channel or news outlet to really focus on the use of white phosphorus. Part of the reason why Israeli officials were not able to deny it for very long was because of evidence we were presenting, which was later amply documented by Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International. Our correspondents pointed out an odd-looking white powder that was falling from the sky, which later was determined to be white phosphorus by experts on the ground. I think we did our job in constantly keeping the pressure on, and constantly reporting what was happening. Our team of correspondents in Gaza were extremely courageous, and they were not emotional in their coverage. It was very fact oriented.

SB: It’s an interesting development — how with constant coverage, reporting can potentially serve as evidence in future legal cases about, for example, human rights abuses.

GF: It can be important evidence in the end — it helps us get to the bottom of what happened in any given war or conflict. Holding people in power accountable, while showing viewers exactly what is going on. Even the Israelis realized the significance of engaging with us. Ironically, an Israeli network dropped a major television channel and picked up Al Jazeera English. Given the amount of airtime we give to Israeli officials, I don’t think there is any bias there.

SB: News stations seem to disclose their innermost moral, ethical, or ideological positions during the broadcasting of war, in what they show, and what they don’t show. What role does war play in the identity of a news station, in your opinion?

GF: If you call yourself a news station, then you simply cannot ignore the facts that go along with war — how it begins, where it starts, how it unfolds, and who the players are. You look at the current situation in Sri Lanka. We constantly have people from the Tamil Tigers on, we’ve spokespeople for the Sri Lankan government that come on, and we try to get to the bottom with each side, whether they are using heavy artillery against the other side when they said they had stopped. It’s a very useful medium to understand what’s going on, and to put pressure sometimes, and help uncover a truth that wouldn’t otherwise be known. Any news outlet that doesn’t do that wouldn’t be fulfilling its responsibilities. You have to show the ugly effects of wars because wars are ugly. There are no options there.

SB: Obviously Al Jazeera English, since its start in 2006, has covered events in Iraq, but there was something maybe unique in the Gaza conflict. It had a clear beginning, a clear buildup, and a supposedly clear end. In dramatic terms, you could say it had three acts.

GF: Supposedly, yes, everything should be clear, but then you’ve got different players arguing their cases on different networks, and the picture becomes murky. During the war in Gaza, there was this whole debate about when the ceasefire had been breached and by whom. We had Israeli officials coming on regularly with their rehearsed lines, and quite often their words went unchallenged. The onus was on Hamas, whom the Israelis claimed had broken the cease-fire. When the facts revealed a different reality, this is where we come in. There was an event on the fifth of November in which there was an Israeli attack, but without even going into those details, I can safely say that we played an important role in making sure the truth did not get lost between facts and propaganda.

SB: A slight change of theme, Ghida. I’m wondering, what do you like about the process of interviewing, and what do you think its limitations are in relation to print media?

GF: Part of why I do this job is to interview some of the key international players who shape some of the most important events of our time. I find it is a rare privilege to sit face to face with a broad range of political figures and ask them questions that others, the viewers, would want answered. I think it puts a lot of pressure on the interviewer, certainly on me, because you’ve got a certain amount of time and a recorder in front of you, and you want to use it well, get the most out of them, be it an admission of something specific or information that is lacking for the understanding of a given issue. TV versus print, I mean — I have done interviews for both, and I think they both have their advantages and disadvantages. In my experience, I think there is an added value in seeing someone’s expression and being able to immediately capture what they see, and doing it live, even though in today’s Internet world, I think, whatever you put down in print has a way of making itself known to the entire world. But again, I think there’s something special about doing it on TV and for TV audiences.

SB: Could you feel yourself getting better at doing interviews over time, or did you start in control as an interviewer?

GF: I think that if I look back maybe ten years ago or more, it’s always been a passion of mine to do those kinds of long-format interviews with people who have something to contribute on a hot-button issue. I’ve always been attracted to that aspect of journalism. Of course, the more you do it, the more confident you grow, because it is not always easy to confront a head of state or government. Some will try to put you off, as a way of trying to control the interview, so you just have to come well-equipped with the facts.

SB: You just mentioned control. Do you like or dislike being interviewed? Can a hardened interviewer, who has interviewed heads of state and political giants, ever relax enough to be an interviewee?

GF: No, I think I would much rather be on the other side of this interview, be the one asking the questions. It’s easier because you are the one in control, there can be no surprises… or almost none. It is always a challenge to honestly answer other people’s questions. I like to put myself through that occasionally, but I must say, not too often.

SB: We are very privileged, then! Speaking of being off air, the daily media and news, by definition, never stops. Can you escape from it? Is it important to you to switch it off, or is that a luxury you don’t have — or don’t want?

GF: You can ask my husband! He will complain that I can never switch off, it’s either the Blackberry or the Internet… Some friends used to tell me that journalism is almost like a drug — now I understand. I still find it difficult to switch off, even when I am on holiday.

I remember when the events started to unfold in Gaza, I had a trip planned, finally a long-awaited holiday, and I had a flight the next day, but one of the editors said, “We suspect there is a ground invasion that will happen in the course of the next twenty-four hours, would you mind coming to work on the weekend even though you are supposed to be off?” I immediately said yes, because it was such an important story for me to cover. I could not see myself lying down on a beach, relaxing while this was going on. On a general day-to-day basis, I think there is a temptation to always know what is going on in the world. So now, even though I am talking to you, relaxing on a day off, in the background I’ve got the TV on mute, and I can monitor the latest on the swine flu.

SB: What are you reading at the moment? Escapist fiction, or another Robert Kagan thesis?

GF: To prove to you that I can’t switch off, I am reading a book on US political history that I began during the US election and only managed to get through half of — Team of Rivals by Doris Kearns Goodwin. It’s about Lincoln and the team that he put together when he became president.

SB: So, is there ever time for a Dan Brown blockbuster?

GF: Hopefully not.

SB: Okay, Ghida, my last question…

GF: Alright, make it a good one, then.

SB: Let’s try! If Bidoun had the power to organize an exclusive interview with anyone who has ever lived in the history of mankind, who should that be, and why?

GF: Ah, the power of the media. It could be a number of people, let’s see. It’s a tough one — you said you would make it easy. I did think about it before we began.

SB: You must get asked that all the time.

GF: All the time, of course. I’d have to go with the current time frame. If I could interview someone this very day or, say, in the last year — I would say Osama Bin Laden. Simply because it’s a mystery as to whether he is even alive. Having the opportunity of telling the world he’s here. So that’s one. It would make me very unpopular with some American viewers, though.

SB: Let’s open it up. They don’t have to be alive anymore. Who else would you want to interview?

GF: Well, nothing too far back in history. I would have to say Saddam Hussein. It would have been great to have been able to sit down with him and really press him on all those so-called weapons of mass destruction.

SB: I would love to ask him about his bizarre taste in art and paintings.

GF: What do you think it might have been?

SB: Have you not seen the pictures? They came out when the palaces were stormed.

GF: Really?

SB: Saddam had a real penchant for buxom Dungeons ’n’ Dragons warrior women, bare-breasted, fighting mythical dragons. It was very, very strange. Like the kinds of things that you would see in a spotty teenager’s bedroom, perhaps. They were all over one of his palaces.

GF: This is where you and I might have teamed up! I would have done the hard-hitting, no-nonsense questions about the weapons, and you may have done the more interesting, exotic ones.

SB: I’d have asked him, “Why in one of your personal bathrooms did you have seven sinks?”

GF: Did he?

SB: Yes!

GF: I’ll tell you, I did go to Iraq in the summer of 2003, after the invasion, as part of a group of journalists traveling with the former US Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, and we stayed in one of Saddam Hussein’s former palaces, renamed Camp Victory by the Americans. We slept on military cots in one of the guesthouses surrounding the palace. I didn’t see the seven sinks though. I didn’t get close enough.

SB: I’ve got a picture — I’ll send it to you. No evidence of WMDs. But we’ve found the seven sinks.

GF: And that’s how you nail an interview.