Dubai/UAE

Alex Bach: I’ll Be Bach

December 2003

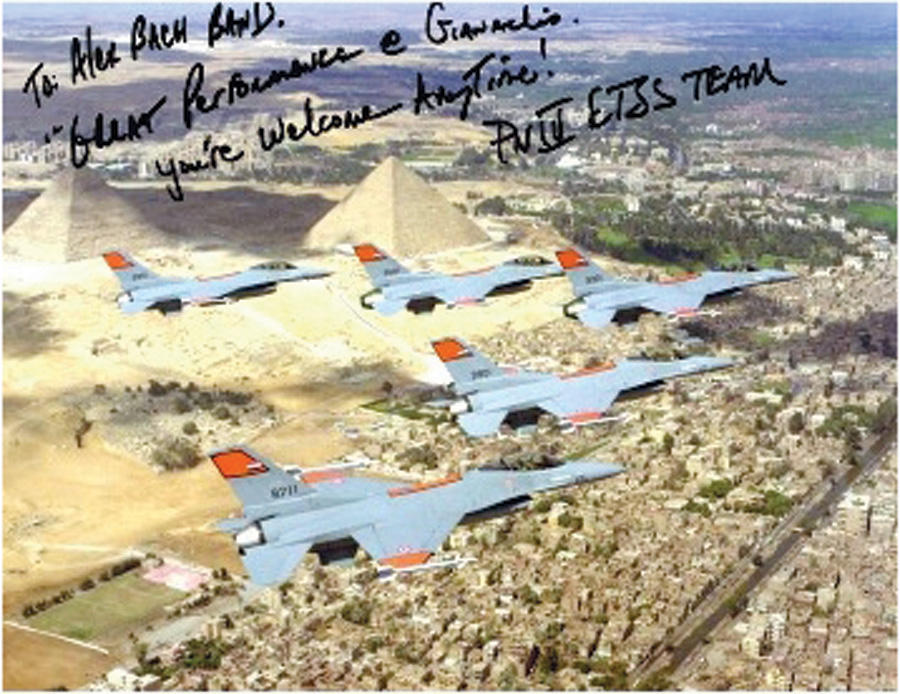

For those of you who have tired of Bono and the Dixie Chicks, here’s a new pop rock activist for you: virtuoso Alex Bach plays for US troops in the Middle East.

“Al salamo alikom ashkedaie!” reads the certificate of the Egypt Office of Military Cooperation, thanking US rock musician Alex Bach for joining the Forces’ entertainment in Abu Hammad in December 2003, and maintaining the “high morale” of military personnel. Following Egypt, Bach went on to play for troops in what is mysteriously termed, “unidentified parts of the Middle East,” where helicopters zoomed by en masse while she had armed escorts at her side wherever she went.

So will Bach soon be playing her rock music, a sugary blend of Brian Adams and new metal, at a Mideast venue near you? “I’ll Be Bach!” is the reassuring slogan gracing the t-shirts on Alex’s website. One thing is for sure: Bach believes in fighting for a good cause. Over in what she lovingly refers to as “somewhere in Bumf**k, Egypt,” Bach regained appreciation for “grocery stores, restaurants and music stores that open late.”

“I do realize,” she explains, “that to have these amenities, sometimes we have to fight for them.” World citizen Alex Bach spent a good part of her childhood in the Emirates, and reportedly still speaks Arabic. This is why she can offer us a rare, insider’s perspective on the region, which she describes as filthy and volatile.

A glance at her tour schedule reveals that Alex will be performing in downtown Boynton Beach as well as the Brass Mug in Tampa. Hardly the kind of venues that will get her back on the evening news, so maybe she’ll be Bach sooner than you think. Perhaps — who knows? — at the Azadi stadium in Tehran? Or will it be “Al salamo alikom Damascus”? “Ali salamo Ramallah”? Keep checking your Time Out Dubai for details.

Istanbul

Zaha Hadid: A Monochrome Model

Garanti Galeri

November 30, 2004–January 15, 2005

Zaha Hadid has a thing for Istanbul. She visits regularly, stays at the Ciragn Kempinski and has been spotted shopping in the up market district of Nisantasi. So perhaps it is only apt that the second exhibition devoted to a single architect ― the first was Steven Holl ― at Istanbul’s architecture and design gallery Garanti Galeri (GG) is a review of recent work by Hadid.

GG is the sister gallery of Platform Garanti Contemporary Art Center. Its space, also on Istiklal Caddesi, is smaller and more corporate in design than Platform’s, and whereas Platform only has to incorporate a a cashpoint to denote its connection to the Garanti Bank, GG has to endure the street’s main branch residing on its shoulders. In spite of these more rigid features, the new GG space has been promoting product design, urban planning considerations and architectural exhibits in educational and expressive ways. GG has also established a devoted and extensive audience base: last year a lecture by Steven Holl, held to coincide with his exhibition, filled the auditorium of the Hilton Conference Center. If all goes to plan and Zaha Hadid finds the time to speak in Istanbul in January, there will no doubt be queues at the door.

The size of Hadid’s exhibition proposal reflects the modest budget and the modest space available, and yet the installation offers a concise reading of five of her most recently realized projects: LFone Landesgartenschau, in Weil am Rhein, Germany; Car Park and Terminus in Starsbourg, France; Bergusel Ski Jump, in Innsbruck, Austria; the Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art, in Cincinnati, Ohio, US; and the Phaeno Science Center, in Wolfsburg, Germany.

The collection of these works offers an opportunity to consider the variety of Hadid’s recent buildings — work that earned her the prestigious Pritzker Prize in 2004. In two of these works Hadid transforms potentially mundane spaces with dynamic architectural moves. The natural sweep of the highly specialized sports apparatus of the ski jump is dramatically extended to link the café and sundeck poised at its peak. In her car park, the slight shifts in the orientation of the parking spots hijack the cars, incorporating their transitory presence as a formal element of the design. The frenetically elegant Cincinnati Arts Center and the ambitiously fluid Science Center in Wolfsburg are cultural institutions that allow for a fuller implementation of Hadid’s vision.

In mounting the exhibition, the design team has covered Bulent Erkmen’s wall cladding (that supposedly offered a flexible display system for the gallery), returning the space to the paradigm of a clean white cube. Large-scale photographic prints of the buildings in question have been mounted on the walls, four finished and one under construction, all taken by the well-known architectural photographer Helene Binet. Binet’s practice focuses on the contrasts, shadows and negative spaces created by contemporary architecture. Here the viewer is dwarfed by the images that draw you into the concrete interiors and entrance spaces they depict.

In the center of the room a sample of white museumboard models sit on plinths. The exhibition’s monochrome nature draws the visitors’ attention to both the details shown in the photographs and those carved in the models. At the entrance a collection of plans owe their only 3 dimensional quality to the intricate folds and cuts applied to a sheet of card. These delicate techniques used by Hadid’s studio suggest the delicacy of origami creations, or pop up cards, that have no more purpose than to exist at the scale they were conceived. But of course these models are proposals for human use. The intense concentration required to shift one’s imagination to another time and scale, also influenced by the looming photographs and the whiteout effect of the models themselves, is seductive.

In contrast to the steadfast elements, two animated videos, one playing at the back of the space and the other projected at night on the window of the gallery, explore the same buildings further. It is here that color emerges. And while such animation often allows for the most easily understood and informative description in the exhibition of architectural design, Hadid’s models are so explanatory that the moving images provide little more than a backdrop for an already accessible, engaging display.

Beirut

Halim Mahdi Hadi al-Karim: Layers of the Soul between Hallucination and Schizophrenia

Espace SD

January 13–February 5, 2005

Something of an anomaly in Beirut’s ersatz art scene, Espace SD is a large, austerely designed contemporary art gallery that negotiates the fine line separating the commercial from the critical, the retro bougie from the cutting edge. In addition to its size, Espace SD’s location is an asset — with its proximity to Beirut’s working port and the presence of massive floor-to-ceiling windows lend themselves to a give-and-take dynamic with the city. Few artists have successfully explored the gallery’s public-private rupture, but as of January, the Iraqi-born, Holland-based artist Halim Mahdi Hadi al-Karim is giving that aspect the full treatment.

Karim’s exhibition, Layers of the Soul between Hallucination and Schizophrenia, is about light, transparency, and weightlessness (philosophically in tune with Milan Kundera’s Unbearable Lightness of Being). Although now based in Amsterdam, Karim has family roots in Lebanon and has been studying the effects of SD’s windows on occasional visits home, spending hours at a time feeling out the space.

In the past, Karim has labored to make metaphorical meaning out of windows in his work. Twisting the classic picture-plane as window-fame conceit, he has conceived of paintings and wall hangings as thresholds between various states of being. Whether they manifest themselves as gateways, portals, doors, or deep gashes in canvas representing an orifice on the female form, for Karim, these windows represent layers of consciousness and tissues of experience.

At Espace SD, he is pushing that idea further. Karim is overhauling the entire gallery space to give it the feeling of an old souk. In addition to works strewn across the floor and fabrics slung from the track-lit ceiling, he plans to hang nine translucent panels in each of those huge windows, toying with acts of exposure and concealment, of looking in and looking out.

Karim’s hand at titling can sometimes make for unkind readings of his work. His emphasis on the soul, dreams, and states of consciousness can cause the jaded to assume his has read entirely too much Carlos Castanada. But the idea of layered experience has concrete roots, attached to the places Karim has lived in, left behind, been forced from and pulled to. All those locales dwell in the domain of memory, which is itself a suspect space. The real window in Karim’s work opens up onto his own headspace, where scientific, psychological, and spiritual sources compete for adequate forms of representation.

At his best, Karim distills his ideas into sharp, singular gestures. In this show, for example, there’s a certain poignancy to the faint impression of handprints detected on paintings and silks, as if to say someone was here, at some point, at some time, someone left their modest mark on this thin layer of fragile skin.

New York

Mapping Sitting: On Portraiture and Photography

Grey Art Gallery, New York University

January 13–April 2, 2005

The Beirut-based Arab Image Foundation presents Mapping Sitting at NYU’s Grey Art Gallery — Walid Raad and Akram Zaatari’s mega-rumination on the place of the portrait photograph in the Arab world. Drawing upon sources as disparate as group military photographs from Iraq and Egypt, and “surprise” photos taken in the Lebanese town of Tripoli, Mapping Sitting offers an alternative view of vernacular photographic practices, defying mere aestheticization tendencies and instead, examining the nuances of portraiture as a social practice in itself.

The result is a presentation that, once placed in the gallery, negotiates a fine line between history as presented in the museum and, oddly enough, contemporary art. In this context, a variety of media are used in exploring the range of representational issues raised by the portrait. Even the archaic photo, a relic of the past, is mediated through video, as projections of military photographs render assembled soldiers larger than life. Suddenly, the bounds between the photograph and the moving image are impossibly blurred — portraiture becomes performance becomes cinema and so on.

Also within the exhibition, a series of passport reference albums from the studio of Anis el Soussi emphasizes the tangibility of the archive in exaggerated fashion — the reality of these photographers as markers. Fellow studio portraitist Antranik Anouchian’s portraits are reproduced en masse, lining the walls of the Grey Gallery space, globalizing the portrait and raising questions as to the art of classification. Hashem El Madani’s beach and tele-ferrique series showcase notions of leisure as played out before the camera. The prolific Saida-based Madani was canonized late last year in a Photographer’s Gallery exhibition curated by Zaatari and Lisa Le Feuvre.

Here, photography is far from the fetishized icon, for the Foundation’s selection stresses neither the potential for fantasy in self-representation (the classic Hollywood-inspired portrait) nor the exoticism of the other (the picture postcard), but rather engages with the photograph as commodity. Revealed within these halls are a glimpse of how we have negotiated our places in relation to notions of modernity at large — and, if you look hard enough, an insight as to how that legacy continues to inform the present.

After closing at the Grey Art Gallery, Mapping Sitting travels to the Krannert Art Museum at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, where it will be on view from April 16 to June 5, 2005. A more extensive tour is in the works.

Moscow

The Dialectics of Hope

Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art

January 28–February 28, 2005

The Dialectics of Hope is a sufficiently lofty theme to encompass the opposing poles of trite handholding and the hysterically apocalyptic. Whether it catches the many nuances in the middle will be the test of the first-ever International Moscow Biennale, the next in an ongoing series popularly known as The International Biennale. The Moscow exhibition, for its part, will be an extension of a great inclusionary experiment that counts among its highlights Okwui Enwezor’s Johannesburg Biennale (1997) and Paulo Herkenhoff’s Sao Paulo Biennale (1998) — products of a decade-long flirtation with the international given an often narrow, Euro-American conception of the art marketplace.

An all-star curatorial team (Daniel Birnbaum, Lara Boubnova, Nicolas Bourriaud, Rosa Martinez, Hans Ulrich Obrist), combined with Joseph Backstein of Moscow’s Institute of Contemporary Art, hold the potential to engage the city in a manner that speaks volumes to the particularities of place, but also has resonance for so-called peripheral spaces at large (the irony of calling Moscow peripheral is not lost). Fifty artists — among them Christian Boltanski and Bill Viola — will exhibit work in a series of state-owned museums, monumental spaces that bear the names of Lenins, Pushkins and beyond.

And Moscow is not just another venue. Thirteen years after the great undoing of the Soviet Bloc, Russia is renegotiating its place in the world. What to watch out for will likely be the Russian artists featured, not to mention those hailing from the immediate neighborhood of satellite states that equally find themselves facing existential questions surrounding future-hood, hope and the like in the shadow of the (former) big daddy.

Finally, the Biennale’s self-proclaimed goal of “reintegrating contemporary Russian art into the international art world” sounds good, but then for a former superpower, why not turn the tables? Reintegration sounds like a civilizing process, a reconciliation project that aims to access the canon, or in this case, the market. Note there is far more to be gained here.

And why the dialectical nature of hope? Why Hegel? This may in fact be the key to the Biennale’s success: embracing the complexity, defying the one-dimensional. Perhaps things are not so simple in Moscow as the average post-colonial, post-communist manifesto. In principle, things are looking good from this end.

London

We Have Met the Enemy and He Is Us

Redux Gallery London

February 3–28, 2005

Bridging the metaphorical, social, cultural and often times constructed divide between “us and them” is difficult terrain. The situation becomes a bit more complex when the ethnic or historical origins of one or more of the parties becomes a stamp — the only stamp. All too familiar with tired labeling tendencies, contemporary London based artist Shezad Dawood has curated a group show critically questioning such an approach. We Have Met the Enemy and He is Us includes the work of artists Rasheed Araeen, Reza Aramesh, Shezad Dawood, Babak Ghazi, Mustapha Hulusi and Runa Islam.

By referencing the standard formulae often applied to the formation of group shows, Dawood’s selection of artists has been informed purely on the basis of the artists’ Islamic names. No conspiracy intended. The selection questions the notion that all artists from the Islamic world necessarily connect with one another through a unified practice and belief system. Indeed, the assembled artists could not be further detached from one another, in every sense.

Take the film work of Islam, for example (Stare Out) Blink, (1998). The artist uses video to reexamine the notion of self-portraiture and the female “gaze” through the image. A woman stares intensely at the viewer, demanding reciprocity — only to suddenly disappear, leaving her ghostly mark imprinted upon the observer. A reappropriated poster by Hulusi, Mustapha Hulusi, (2003) is inspired by Victor Burgin’s 1970s-80s political posters, such as Possession. Hulusi has reworked the broadsheet by inserting his own name into the body of the text — an act that suggests both an art and historical protest in which he highlights his own personage in both histories. While there are representational approaches that tie together works within the show, the ethnic stamp is certainly not among them.

We Have Met the Enemy and He is Us hopes to defy curatorial practices rooted in ethnic rubrics. Artists are placed within a super ghetto in which the “enemy” is both central and peripheral. The show’s aim is to express a mixture of indifference and defiance against any classification process, presenting works that embrace nuance rather than absolutism.

Sharjah

Emirates Fine Art Society Members’ Exhibition

Sharjah Art Museum

February 2005

Any visitor to the superficially culture-starved UAE would assume that the Emirates Fine Art Society specializes in the usual touristand palace-oriented watercolors of romanticized desert scenes. But the Sharjah-based organization has its gaggle of multi-media contemporary artists, thanks largely to the influence of Hassan Sharif, the father of the conceptual mini-movement in the Emirates. Sharif, together with local theorist Talal Al Muala, is curating the 24th annual outing for the three hundred members, selecting key works that fit with the theme of al tabadul (interchange). At the time of writing, only a handful of artists have been confirmed. These include Khalil Abdulwahed Abdulrahman, whose disorientating video work examines artistic process and practice, as well as the stuff of the everyday; Mohammed Kazem, who works in installation and photography, chronicling the heady pace of commercial development in his native Dubai; multimedia artist and sculptor Hossein Sharif; and Abdullah Al Saadi, a painter and installation artist who focuses on the “memory” of found and traded objects, usually exhibited on the seashore in Khor Fakkan near the Oman border.

Some of these more established artists have had outings internationally — through the last Sharjah Biennial and exchange projects in the Netherlands and Germany — but the exhibition should be a revelation to those who include only the UAE’s myriad of commercial art showrooms specializing in desert exotica in their gallery beat. The organizers promise that the show will also include emerging artists working across all media, allowing critics to size up whether Sharif and co have managed to impart their “pluralism” to a younger generation.

Cairo

Wael Shawky: Circus

Townhouse Gallery

March 17–April 10, 2005

Wael Shawky draws upon the historic space of the circus in his March exhibition at Cairo’s Townhouse Gallery. Erecting an enormous cloth tent within the gallery’s factory, complete with theatrical lighting and the works, Shawky intends to recreate the spectacle of the iconic American tradition in the unlikely context of Egypt.

Nevertheless, this particular circus tent is oddly reminiscent of an Egyptian shader, a cloth enclosure used for both weddings and funeral. In this way, Shawky collapses boundaries of geography and even time in evoking spectacle, differentiation and the consumption thereof. In his execution, fiction meets reality; the artist draws upon documentary-style videotaped testimonies as projected in a mini-theatre within the circus — finally confusing us as to where reality ends and the fiction of performance begins.

Elements drawn from popular Egyptian life, such as the tradition of commercial comic theater (think evoking the midget) suddenly have remarkable parallels to the iconic history of the circus. Equally, Shawky references the fashion industry, engaging models, raising questions as to the performative nature of that particular industry subculture. Like the acts on display in the circus context, the models serve an audience poised for consumption of that which is different — here as manifest in a freakish construction of perfection. Yes, Shawky says, it’s no wonder Diane Arbus got her start working for fashion magazines.

Shawky, whose body of work is often marked by a concern with globalization and its discontents, seems to be extending these ruminations in this exhibition — here, veiled as a ubiquitous culture of capitalism = consumption = spectacle. The fact that this exploration is taking place within the context of the art market adds a further layer of complexity. His message: the circus is all around us.

Sharjah

The Seventh Sharjah International Biennial

April 6–June 6, 2005

In April 2003, on the eve of the US invasion of Iraq, director Sheikha Hoor al Qasimi and curator Peter Lewis opened the ’Sixth Sharjah Biennial’ and transformed the fortunes of contemporary art in the Gulf. Previous biennials had been provincial, painterly affairs; this behemothic exhibition, complete with a symposium and an incomprehensible doorstop catalogue, featured over 100 international artists working across all media. So far, so humdrum to global art trippers; so far, so radical for culturalists in the Gulf, even the Middle East.

The 2005 Biennial promises the same edgy delivery, but a sharper, more focussed approach under curator Jack Persekian, director of Jerusalem’s Al-Ma’mal Contemporary Art Foundation. Qasimi, daughter of the ruling Emir, is again directing the two-month-long event. Astutely, they have brought Ken Lum and Tirdad Zolghadr on board as associate curators.

This time around the organizers are keen to wed the transnational format of the art biennial to the event’s locale. An accompanying symposium will debate “biennialicity” — the nature of the art biennial industry and how this new(ish) tradition has influenced the consumption of art. Meanwhile, the curatorial approach foregrounds the question of “belonging and unbelonging in a context of change” — specifically, and fascinatingly, the rapid commercial developments taking place in the UAE.

The curatorial team is selecting around fifty international artists. They will show their work, much of it site-specific, in the “traditional” galleries of the Sharjah Museum of Modern Art and in the nooks and crannies of the city’s central Heritage Area. This setting itself raises key questions; in the words of the organizers, it provides a “kaleidoscopic fabric of shifting social structures, long-standing traditions, consumer cultures, archaeological assets, modern and postmodern architectures, and other interfaces including the biennial itself.”

Besides the exhibitions, symposium and catalogue, there’ll be a competition, overseen by a jury that includes Rina Carvajal and Okwui Enwezor. Readers weary of identity issues — post recent biennials and Documentas — should stay with this one: the curators promise that those standard enquiries will be tested to the limits, beyond the comfortable frame of a customary artworld gathering.

Beirut

Home Works III: A Forum on Cultural Practices

April 8–15 2005

In its third edition, the Home Works Forum is among the premiere self-styled international cultural experiments hosted in the Middle East. Bringing together artists, writers, intellectuals, filmmakers, architects and beyond for a period of eight days in Beirut, organizers Christine Tohme and Rasha Salti of the Lebanese Association for Plastic Arts (Ashkal Alwan) have set the foundation for a revolution in prevailing representational tactics today. In its first two years, Home Works, known simply as the Forum, has managed to reveal the strength of homegrown expression, finally affirming the region and its Diaspora’s own agency in playing the oft-tricky game of culture politics. In this neighborhood, the Forum provides an unprecedented venue for critical international exchange, not to mention a premiere venue for the visual arts. This time around, as in past editions, the Forum has commissioned works from a number of emerging and established visual artists, writers and beyond.

The principle guiding the forthcoming edition of Home Works is largely self-reflective — a self-proclaimed “exploration of the notion of our being in this world, as reconstituted in narrative and representation.” The Forum’s mission statement continues, “We must assert the fact that we are not merely a face caught on a security camera, a stamp on a passport, a fingerprint filed in a court, a visa denied, a stereotype confirmed, or a silent misunderstanding hardened into unspeakable fact.”

Overtly political perhaps, but what artistic expression is not at least mildly political in this region and, furthermore, in this global climate? Enter the Forum, Beirut’s own novel artistic platform. Importantly, the event challenges participants to initiate a critical reading of their own works in relation to the specificity of their lived context. What is the epistemological value of the past, the role of political crisis and social ruptures in the construction of alternative histories? Participants from Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, Iraq, Turkey, the United Kingdom, Jordan, the Netherlands, Italy, the United States and Iran will be engaged in a variety of multidisciplinary interventions, including lectures, public performances, exhibitions and screenings.

As in the previous round, Ashkal Alwan will produce a series of novel publications in conjunction with the Forum, an invaluable task given the dearth of local references on the arts.

Istanbul

Istanbul Modern

Opens December 11, 2004

The new Istanbul Modern has certainly been getting love from European figureheads. German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder compared it to New York’s MoMA, London’s Tate Modern, and Paris’ Centre Pompidou, while British PM Tony Blair was a bit more transparent when he said, “As we look ahead to the prospect of Turkey joining the European Union, it is increasingly important that the world learns more of what Turkey and Turkish people have to offer us.” And there is a lot being offered for Tony to sink his greedy little teeth into.

The museum launched last December in a newly renovated 8,000 square meter space on a pier in Istanbul’s port. Its primary mission is to tell the story of 20th century Turkish art; but in order to join the ranks of other cultural capitals, an institution must push in all directions. Accordingly, the Istanbul Modern includes a gallery for temporary exhibitions; a sculpture garden; a dedicated photo gallery exhibiting three shows year; a new media gallery where visitors can tap into a wireless network; an education program that promises to edu-tain 20,000 school children in its first year; a research library open to the public; and a stellar cinema center featuring exclusive independent films, festivals, and midnight movies on the weekends. There is also the upscale Museum Café put together by the trendy Loft restaurant and a gift shop where you can find all of your favorite Turkish artists reduced to posters and mouse mats.

Architecturally, it has all of the subdued yet impressive qualities of most other international museums. Hopefully the museum will grow into its new space by figuring out how to hang shows in a way more conducive to viewing and jettison the iffy titles like “Touching Time” and “If Walls Could Speak” that break up the rooms of paintings in the permanent collection.

Kicking it off in the temporary exhibition gallery is a retrospective of Fikret Mualla, curated by Ferit Edgü. This exhibition will run until March 2005 when Spanish curator Rosa Martinez will announce her presence as head curator with a show called This is Just the Beginning. Martinez has curated many shows on the international scene notably the 5th International Istanbul Biennial in 1997 and she is currently curating the upcoming Venice Biennial. She therefore seems to be a good fit for a museum looking for an interlocutor between Turkey and the rest of the EU (and beyond).

All in all, this ambitious project will certainly be a point of pride for the people of Istanbul, but those in its art world will be a little bit harder to please. Some are already lamenting the missed opportunity to construct a truly local museum that blazes a new trail and avoids the pitfalls of the internationally standardized touristic spectacle museums.