I was working at the magazine as a fact-checker and my parents no longer considered me a failure, not because they read or admired it, but because when they said its name to friends and relatives it sparkled on their tongues. I still wasn’t a doctor or engineer, but the publication cast a flattering light on them, revealing them to be open minded enough to let me pursue a non-traditional field, yet strict enough to propel me to its most rarefied strata. I liked to name-drop where I worked, too, especially when meeting someone for the first time, though I made a point of not bringing it up until I was asked. For almost two years, things went smoothly. I had insurance and I was making more money than ever before. At work, I checked a lot of the “back of the book” pieces, which often involved going to the movies or reading novels on company time. I would write emails suggesting minor corrections:

Almodóvar’s debut was released in 1980, not 79 as is written, and Penelope Cruz’s character has sex in the first ten, not five, minutes of the film. Screenshots with timings attached.

I would then spend the rest of the afternoon sitting in an armchair by the windows, watching the sunlight arpeggiate the water in the 9/11 Memorial fountains. The magazine was full of loveable weirdos who knew inordinate amounts about cuneiform or animal husbandry and were prone to causing collisions in the hallway because their faces were buried in paper proofs. Many of my colleagues reeked of money: hyphenated names, signet rings, private schools, Prada frames. My family had money, too, though I don’t think I got the job because of my pedigree, but because I spoke Arabic and English without an obvious accent.

Fact checking rewards the kinds of neuroses that can make me intolerable to friends and family. At work, I could chat without embarrassment about why I preferred Mahler’s tenth symphony to his ninth, or about the origins of the fascist accents on the columns at Grand Army Plaza. Still, I knew that certain things fell outside the protection granted by eccentricity, so I pretended my ambient anti-Americanism was ironic, the product of reading too much critical theory in college.

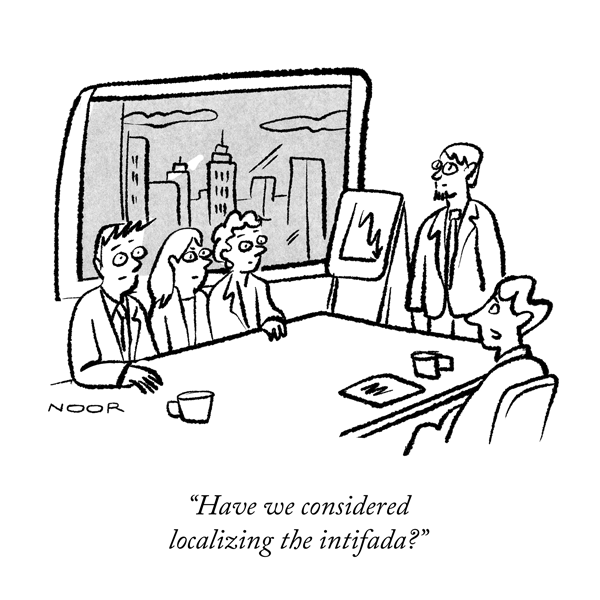

The magazine’s politics were what passes for center-left in the United States. The editor-in-chief once told us that the geographic distribution of our subscribers was nearly identical to Obama’s 2008 electoral map. Wherever I went in New York, I saw white people of nearly every description carrying the magazine’s tote bag around like a talisman, though what they thought they were warding against, exactly, I’m not sure. At work, it was surprising to be surrounded by demonstrably smart people who believed, for example, that Donald Trump’s election was somehow surprising, that meaningful wealth redistribution was beyond the political pale, or that individual human beings, and not systems, were history’s main actors. The operating orthodoxy was that police killings, CIA coups, black site torture, and institutional misogyny were aberrations, deviations from the American norm that would eventually be corrected when the arc of the moral universe, long as it is, finally got around to them.

I insulated myself from this flavor of stupidity by rigorously avoiding news stories, though I knew that one day some Muslims who hated the West would kill some Westerners and I would have to bite my tongue and check some pieces that implied, but never outright stated, that Arabs were predisposed to bloodlust. I hated the West, too. I hated how Westerners were always asking to itemize the bill at dinner, how they never took enough responsibility for, say, inventing fascism and nuclear weapons, or for instigating the Bengal famine. They fought in stilted HR-speak, and shoved bland food into ruddy, clammy faces. My hatred never reached the level of murderousness, though it did put me in a tricky position. I couldn’t “go home” because I had no “home” to go back to; Egypt, where my family lived, was languishing under high inflation and military dictatorship, while the Emirates, where I’d grown up, was a land of indentured servitude. Besides, I wanted to become a novelist, and novelists lived in New York.

The attack happened on a Saturday, while I was at home trying to write a neutral review of a bad novel. As the news unfolded — hang-gliders, pirate Kalashnikovs, a music festival — I abandoned my review and spent the day online. I watched in real time as the consensus congealed; by Sunday morning, everyone seemed to agree that the events of the previous day could only be interpreted as senseless barbarism or perhaps an Iranian plot, but absolutely not as a legible expression of rage by a people the world had left to die. I felt like I was losing my mind. I went to a march with a friend that afternoon and stayed up late writing some of my thoughts, which were published by a smaller, leftier magazine a couple of days later. I was surprised at my own convictions, and I worried that I might have ended what I had come to think of, with an unhealthy dose of self-aggrandizement, as “my career.”

When I next went into work, I kept my headphones on over a pulled-up hoodie so no one would try to talk to me. I was in the middle of checking a difficult piece about fraud in the carbon credits market, anyway, and was prepared to plead busyness as an excuse to avoid idle chit-chat, but this proved unnecessary: people in the hall seemed keen to avoid me. Bombs were already falling in Palestine, the death count mounting by the day. All I could think about was all of the ways that Arabs and Muslims had been fucked over, this century and the last, and how little anyone cared. Across the US, public events that were critical of Israel were being canceled. People were getting fired for expressing demands for a ceasefire or solidarity with Palestine. I thought I might become one of them.

The editor-in-chief came by my desk. He was, my co-workers and bosses always said, a good guy. He really cares about us. They called him Dad. Everyone knew he could make their careers or blacklist them, and they pined for his approval. When he laid people off, he wanted the rest of us to know that it was a very difficult thing for him to do. He said fuck and shit a lot, remembered his employees’ children’s names, and drank cheap Prosecco with us when there was an award or promotion to celebrate. I was certain that he appeared in the dreams of every employee fiscal-quarterly. He told me, once, that he regretted his support for the Iraq war terribly, that it was the biggest mistake of his career. He’d been swept up — you must understand, he said, like I already understood — by the mood of the times.

I started sweating when he sat down, worried that I was about to be fired, though it would have been strange for him to do it right there in front of all my colleagues instead of calling me into his office.

Ish, he said. (I’d adopted the nickname young, when it became clear that Anglophone tongues could not pronounce the letter ‘ayn.) His tone was funereal. How are you?

You know, not good.

It’s just so sad, he said. The glee these people feel about killing. He put his head down and shook it. Your family, are they safe?

I understood then that he was not going to chastise me, that he was seeking common ground with me, the only Arab on the magazine’s editorial staff. I was not untouched by the gesture, though I was pretty sure that he knew my family was Egyptian.

They’re in Cairo, I said, far from the bombing. But we’ll see how things progress in the coming months.

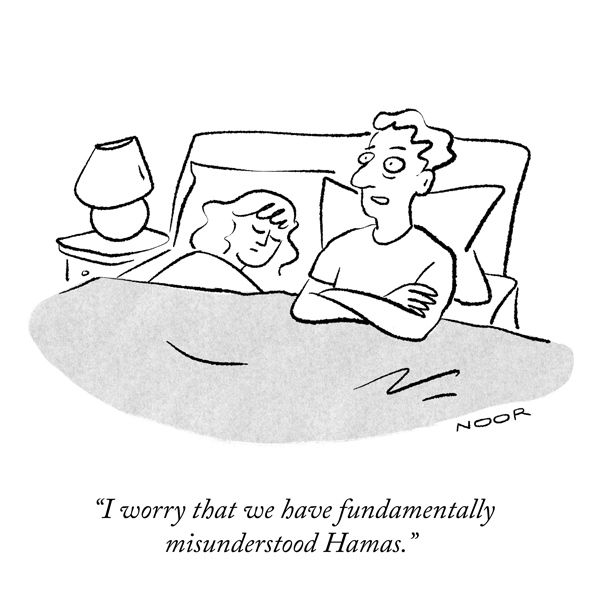

It’s so sad. I don’t understand. Why would Hamas do this?

I didn’t understand why he would ask that. It seemed evident to me that “open air prison” was not a metaphor.

I don’t know, I said. To die on their feet, maybe?

He stared at me, appalled. Look, I don’t agree with it, I stuttered. I’m not saying it’s good, I’m just—

That’s really hard for me to hear right now, he said. He stood up and walked away. Later that week, he flew to Israel to write a story about the funerals and the mourning in the kibbutzim and somehow I was not fired.

I stopped checking movie reviews and spent the ensuing months verifying how many people died in Palestine and the ways in which they died, calling people on the phone to ask how, precisely, their relative had been killed. The work fell to me because none of the other checkers spoke Arabic. At first, it seemed important to me that the language we used reflect the horror of what was happening. But I was defeated in trying to secure the most basic changes:

from: terrorist to: militant

add ‘occupied’ before ‘West Bank’

from ‘Israeli War of Independence’ to ‘the Nakba’

I wrote up a style guide and circulated it among the checkers and copy editors, though I don’t know if anyone ever used it. I started to feel a target growing on my back and stopped fighting as much. I was exhausted. The work was shredding me, and I was not sleeping well. I stayed up late scrolling Twitter and watching Al Jazeera, the tide of images of destruction and death washing over me, leaving me feeling raw and psychotic. When people asked how I was doing, I laughed. Horrible, I said, like it was a great punchline. Friendly members of the editorial staff informed me that some of my older colleagues were calling me a terrorist sympathizer.

Around four months into the war on Gaza, scholars of genocide were reaching a consensus that what was happening in Palestine was a genocide, the crime of crimes, and I waited for the magazine to say so, too. I tried to talk to the editor-in-chief about using the word in our coverage, but he said he didn’t think it was a genocide. The word’s conspicuous absence led me to suspect that he had prohibited its usage among the editors. This was a notable exception to the accepted epistemology; a few months into the job, I overheard another checker cold call an addiction scholar to confirm that gambling was, in fact, addictive. But I did not have it in me to keep fighting. I justified this to myself by saying that the war machine would not be halted by any linguistic alteration I might make in a magazine mostly skimmed over by American suburbanites while they pooped.

I began attending political meetings in support of Palestine. The people I met at these meetings did not conflate reality with necessity; they believed the world could be made otherwise. In cramped lamplit apartments where we could smoke inside, or high-ceilinged, white-walled Chelsea studios, I would scan the assembled faces and time would stand still. Every hand gesture, every word felt eternal to me, a statue. It was, and I mean this sincerely, transcendental, as though when time started up again these moments would somehow escape the ravages of its passage.

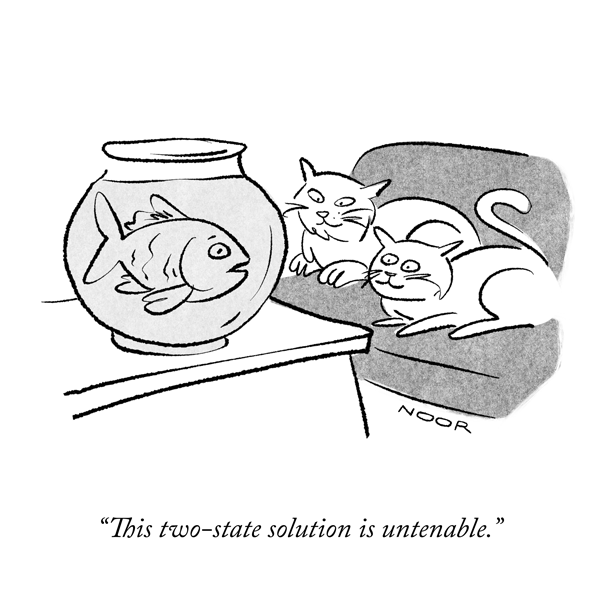

I was assigned, at some point, a piece about a spree of killings and land thefts carried out with impunity in the West Bank since October 7th. The piece mostly focused on a single settlement where a man who had gone to pick olives on his land one Saturday was shot by an off-duty Israeli soldier. His execution had been captured on video. The story included a cast of settlers, anti-occupation rabbis, and West-Bank Palestinians who had spent their lives fearing that their homes would be stolen, and that if they were killed or dispossessed, there would be no recourse for them. I ran into the story editor in the hallway, who said he was having trouble balancing the narrative because all the Israeli characters seemed evil, while all the Palestinians were angels. A long section that documented, without any editorializing, that Palestinian dispossession was an ongoing process that had begun long before October 7th was whittled down to a single paragraph after a series of fights between the editor-in-chief and the story editor on one side, and myself and the freelance writer on the other.

Though the man’s killing had been filmed, a fact checker is obliged to seek comment from any party alleged to have committed a crime. I called the soldier’s lawyer. He picked up from a café, where I could hear trance music blasting in the background. The lawyer told me that while, yes, his client did shoot the man picking olives, and yes, the man did die, the Israeli military court found his client not guilty of murder because the man picking olives was a terrorist who was throwing stones. Even though the video did not show the Palestinian man throwing stones, the court said that he was, so he was. QED, his client did not murder anyone, and it would be slanderous for us to say so.

When I got off the phone, I asked another checker whether they minded taking on the remaining settler calls and was relieved when they agreed. For the next two weeks, I called Palestinians living in the village where the execution had taken place. They spoke a rural dialect of Palestinian-Arabic that I had some trouble understanding, so we would talk slowly, over many hours, and exchange voice notes over WhatsApp. The people I spoke to were devout and searching, lost in a way that I found familiar, though they lived at an intensity I know I am too weak to endure. Two of them had been detained, tortured, and anally raped, and I felt ashamed when I asked them to detail their humiliation for me. Several asked me what they had done to deserve this. They said that they prayed every day that everyone, even the settlers who shot their neighbors, would live in peace, with God’s blessings. Between calls, I ducked into the reference library or the bathroom to cry. When I finished checking the piece, I went into the story editor’s office to deliver my notes. I sat in an armchair, facing the back of his head while he entered his changes onto the computer.

When I left the office that day, all I could do was replay the last few weeks in my head. I thought about the traumatic reenactments I had subjected my sources to, to no particular end. Suddenly, I felt a hand on my shoulder, then someone was pushing me, hard. I stumbled against a curb.

You almost got hit by that bus!

I turned around to see one of my co-workers from the magazine. Behind her, the BM4 bus was hurtling through the point of the Church Street intersection where I must have been standing moments before. Still in a daze, I thanked her for pushing me out of the way. I headed to the F train at East Broadway instead of taking the nearer A train, hoping the long walk would clear my head.

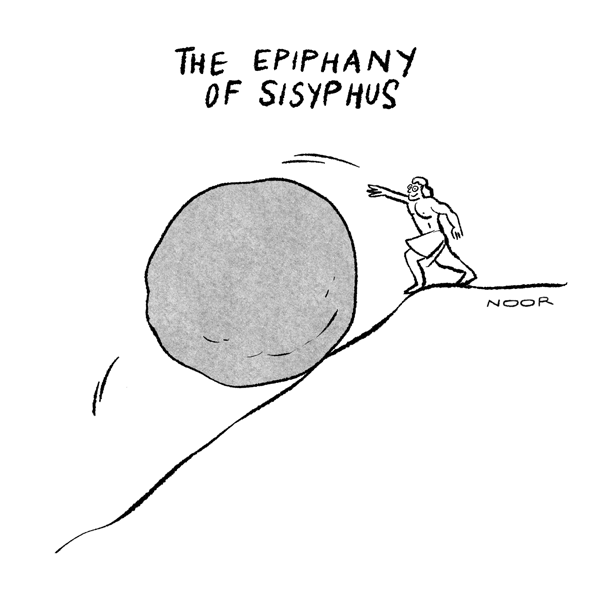

The thought occurred from nowhere, like the urge to jump whenever I’m on a balcony: I could quit. At any time, I could just leave. I knew that if I remained on this path — sequencing, down to the last detail, the annihilation of a people, without working to stop it — then facts would become worthless to me. I knew that someday, years or perhaps decades down the line, when half of Gaza was still rubble and the other half Israeli skyscrapers, the magazine would offer a mea culpa. Maybe someone involved would end up considering it the biggest mistake of their career.

I paced up and down the platform, wondering what I would do for money once I quit. I was giddy with the thought that I wouldn’t have to return to that office. I would no longer feel like I had to reflexively couch my beliefs in qualifiers, or listen quietly to repugnant things, pleasantly said. I felt free.