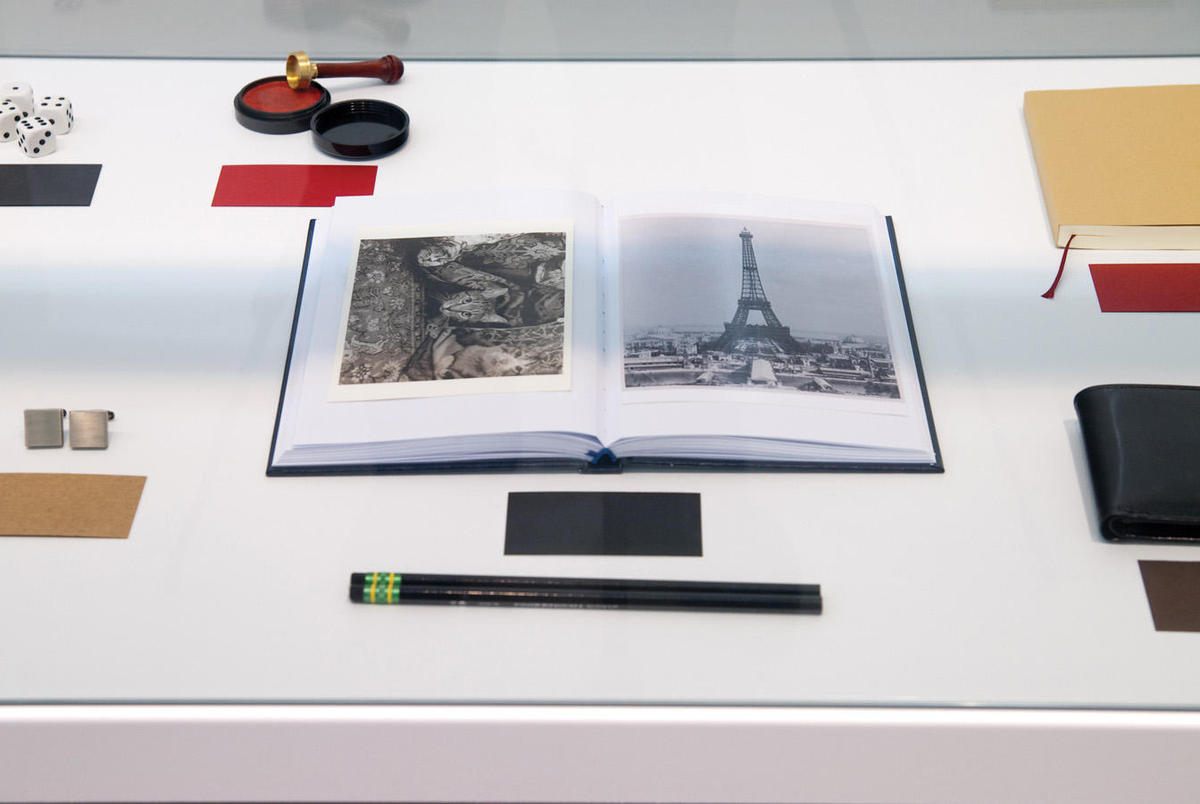

A long glass display case holds a meticulous arrangement of an older man’s effects, including cufflinks, a pocket watch, a letter opener, and two albums of black-and-white photographs. Affixed to a wall close by is a line of text that serves as a title, a description, and a riddle of sorts: Material for a sculpture commemorating an economist whose name now marks the streets and squares he once frequented.

Further along the same wall is Material for a sculpture acting as a testament to both a nation’s pioneering development and continuing decline, next to a pair of bass-throbbing speakers emitting periodic bursts of distortion. Around the corner, Material for a sculpture recalling the destruction of a prominent public monument in the name of national resistance describes an angular wooden form that rests on a high white plinth and is embellished with what appears to be a graduation tassel or the ornament on an Ottoman-era fez.

Since 2010, the artist Iman Issa has been working on a series of proposals for alternatives to public monuments she has known since childhood. Each piece, which Issa describes as a display, pairs a collection of objects with a vinyl wall text. All of the installations forge a relationship between those forms and phrases, but none of them spell out exactly what their affiliation may be. The texts allude to monuments that have for one reason or another failed, but the objects remain something of a mystery, drawing on memory and experience to counter the populism and political expediency of the commemorative statues they seek to replace.

Issa, who is thirty-two, has been composing such precise and elusive works for a decade. Arranged in series, they create artful chains of association among objects, images, videos, texts, and sounds. There is a certain austerity to her style — a pared-down, old school elegance — which sets her apart from the exuberance of youth. Her installations are orderly, her materials relatively plain. Yet this tendency to streamline only adds to the fullness of Issa’s forms — the intense color of a photographic still life, the warm grain of a wooden sculpture, the soft glow of spherical lights. With an extreme economy of visual and spatial phrasing, Issa produces a wealth of possible meanings that always seem just out of reach, on the verge of articulation.

Perhaps this is what binds Issa’s work to that of several other artists who show, as she does, at the Rodeo Gallery in Istanbul. Her projects share the agility and mystery of Haris Epaminonda’s installations and Shahryar Nashat’s videos, as well as the fondness for artifacts, which all three artists explore and question in equal measure. The subtle and oblique manner in which Issa digs into the politics of a place — rarely more explicit than “a city” or “a nation” — also makes her work a smooth fit for “The Ungovernables,” the New Museum’s second triennial of young and emerging artists on view through April 22, 2012 in New York.

Issa showed six of the proposals for alternative monuments in her first solo show at Rodeo last fall. Four more are included in “The Ungovernables.” The series, titled “Material (2010–12),” is now complete at ten displays. The only piece included in both exhibitions is a spartan table adorned only with two globe-shaped lamps that variously dim and shine, next to the title Material for a sculpture proposed as an alternative to a monument that has become an embarrassment to its people. It says something about the fortitude of Issa’s language, with its rules of communication and self-styled syntax referring only to itself, that her work has such obvious and booming resonance but resists being instrumentalized (or even interpreted) as revolutionary art of the so-called Arab Spring.

In one sense, Issa’s work is about radical subtraction. Take the experience of a city, a structure, a monument, a memorial, a campaign poster, a political conflict, an open space, or an evocative story; then strip down the specificities and delete the defining details. But in another sense, Issa’s work is about accumulation. Her projects tend to identify an absence — something lacking or inadequate — and then set out to gather the materials that might possibly fill it in, make it whole, lend it heft, or at least tug it along in a more satisfying direction. Issa also plays a kind of temporal game, breaking down how we encounter images, people, or things. Her works consider, for example, how we might see a statue we recognize, how that recognition might trigger a memory, and how that memory might then give rise to an idea. Each piece in the “Material” series replicates that process, in both the production and the reception of the work.

Issa never divulges the identities of the original monuments on which the displays for “Material” are based, nor does she share the events they memorialize, nor the reasons why they prick her memory. Depending on how near or far you are to her milieu — already an assumption — you can probably guess the name of the economist, the singer, the soldier, or the blind man who became a great writer. You can try to place the resistance movement, the inferior army, or the bygone era of luxury and decadence. But that’s you and whatever baggage you bring to the work. The questions Issa seems to be asking are: What would any of those details really tell you? What more (or less) would you understand? What if the privileges of local knowledge were actually no more than preconceptions? What if the bombastic vocabulary of a public statue was replaced by the strange intimacy and sad delicacy of a dead man’s shoes?

Issa reveals very little of herself in her work, but in person she is open and affable and tells a good story about how she came to be doing the art she does now. “The medium I choose to work with is always only instrumental,” she said to me one day last summer, as we were sitting at her kitchen table with two cups of coffee and a bowl of fruit. “In that sense, going to a bad art school was really good for me. I really started to think about form.”

In the late 1990s, Issa was studying philosophy and political science at the American University in Cairo (AUC) when the school decided to create a proper art department where none had existed before. A handful of students signed up, including Issa, who was making paintings at the time. As soon as she switched, though, she realized the art department was not just new but terrible (“flimsy,” she says now). The BFA curriculum had been cobbled together, nearly at random, from so-called collateral courses in other departments, to the extent that Issa learned photography not as fine art but as a means of mass communication.

Egypt’s universities graduate thousands upon thousands of art students every year, and the general sentiment is that for decades the education system has been failing them all. An artist Issa’s age once told me the only thing he learned at art school in Cairo was how to stretch a canvas — and even that, he later discovered, was wrong. An alumna of AUC who studied there a few years after Issa said the art department back then was definitely chaotic, but in many ways more ambitious than it is now.

What may have been lacking in academia, however, was amply made up for in the life of the city at large. It was a heady time to be young in the Cairo contemporary art scene. Artists such as Hassan Khan, Sherif El-Azma, Maha Maamoun, and Hala Elkoussy were at AUC then and just starting to experiment and embark on their careers. (Khan’s marathon performance piece 17 and in AUC [2003] would later elegize and excoriate this era.) By 2001, new and independent art spaces — such as Townhouse, Espace Karim Francis, and Mashrabia — had reached critical mass and were collaborating on the influential but short-lived Nitaq Festival. The notion that contemporary artists in Cairo were obsessed with their megacity, were ambivalent about its faded cosmopolitan glamour — and actually had a viable alternative to the cronyism and corruption of the state-run fine art sector — was born of this era.

But if AUC students were, like college kids everywhere, famous for their ability to zone out of their formal education, Issa did them one better and left for a year abroad in Seattle. She studied photography in a class designed for architects and, among other things, met her partner, the writer and editor Brian Kuan Wood, who did the sound design for some of Issa’s early installations. In 2001, “I put something together,” she says, walked away from her last painting, and was done with AUC. Six years later, she completed an MFA at Columbia, but she is neither dismissive nor particularly reverent about the program’s reputation as a springboard for young artists in New York.

Looking back at the work Issa was producing in the years immediately after AUC, much of it was either slightly decorative — holographic wallpaper, a room filled with colored lights — or preoccupied with architecture. For Golden House (2003), she made a wooden lean-to, covered it with gold glitter, and set it down next to a highway running through the Sinai desert. Proposal for a Crystal Building (2003) looks like a glammed-up, disco-ready water tower, which Issa displayed alongside a crudely doctored image that took the same sparkling structure (Issa’s proposed crystal building) and grafted it onto the middle of Tahrir Square. Clicking through documentation of these works on a laptop in her studio nearly a decade later, Issa pauses, “This, well, this is Tahrir,” and keeps going. Postcards, posters for public buses, proposals for kiosks, platforms, towers, photographs of faked windows, and Technicolor urban skylines — there’s a fanciful and fundamentally utopian aspect to these projects.

“I was interested in the decorative elements of a city. You see them and expect them to tell you something about the place you are about to enter,” Issa says. “But there’s a gap between the physical encounter and them becoming familiar. It’s a space of doubt. I was stressing the experiential quality but also the ability to recall those elements.”

The architectural structures that Issa built toyed with viewers, who were drawn by the dazzling exteriors and approached them expectantly only to discover there was nothing inside. “I started to worry that it was just a celebration or a critique of spectacle,” she says. The proposals for architectural structures tried to reconcile a different gap, between the city as it was and how urban planners imagined it could be. The backdrop of all of this work was unmistakably Cairo. As she became more interested in the function of memory and how to convey familiarity in relation to places that are both known and unknown, she began to move away from images that were immediately recognizable as the places where they were produced.

“I moved to New York, and I felt I had exhausted what I was working on. I was repeating the same gestures with materials that were familiar. I felt I needed to find other materials. I walked around, took a lot of photographs, and found spaces that reminded me of others. There was a fleeting recognition in an arrangement of lights, or a certain time of day, or movements that were happening in time. The images I took look completely generic, like photographs from an image bank or an advertising agency. Perhaps what I was recognizing was not the presence of something familiar but the absence of a defining detail. I started treating the spaces I found as if they were lacking something.”

One of the works that followed was Making Places (2007), which exists as both a collection of videos and a series of ten photographs. For the first time in her work, a figure appears, holding a mirror sideways, blowing bubbles, throwing a ball in front of an imposing building. Issa tells me a writer once described these works as documentations of performances, “but for me they were never about that.”

Much of the work Issa produced before 2009 was very good, but the real turning point in her practice was the six-part series “Triptych,” which she made that year. Each numbered installation consists of three parts, which a viewer reads from left to right. First, a small, unframed photograph of a detail in an urban landscape, such as a boardwalk or a clock tower or a well-tended lily pond. Then, a larger, framed photograph — a carpenter’s tools; a table crowded with fruit, sweets, and juice — which apes a certain style of lush-colored advertising imagery from the 1970s. Last, a third, more sculptural element, such as a Discman with headphones or a video monitor showing footage of a flashlight rolling back and forth on the floor.

The “Triptych” series is dialogic in that each element is based on and responds to the one that came before. As with “Material,” Issa leaves the meaning deliberately enigmatic. Triptych #5 seems unmistakable in its suggestion that intimate relationships are a complex game of incremental negotiations. The centerpiece image shows a pair of breakfast plates (slices of toast, soft-boiled eggs) arranged on either side of a chessboard set up for a match. But how that relates to the park on the left or the metronome, timer, and flashing lightbulb on the right is anyone’s guess.

“They started out as diptychs,” Issa says. “I started to look at the images I was taking in a removed way, as if somebody else had made them. The third element I really thought of as an artwork. I tried to come up with a concept. It was a kind of labor or bureaucracy gone mad. It was a strange operation.” Perhaps the triptychs capture how an idea moves from a fragile bit of autobiography to a robust and formalist artwork that no longer exposes any of the vulnerabilities of its maker.

The triptychs include an Egyptian flag, numerous evocations of music, and several references to craft or working with one’s hands. One of them, Triptych #4, seems to be about science, medicine, the body, and crime all at once. On the left, there’s an image of streetlights set against an indigo sky at night. In the middle, a still life of a desk with a lamp, a potted plant, an old typewriter, a rack of blood samples, and a thick stack of blank white paper. Next to that is a ledger filled with seven thousand Cairo license plate numbers, which a text explains was compiled by “my sister, my cousin, and myself” and inspired by reading too many detective novels in the summer of 1992.

As much as architecture and photography dominate Issa’s oeuvre, there is also a distinctly literary sensibility running through her work. Thirty-Three Stories About Reasonable Characters in Familiar Places (2011) is a slim book of short fiction that fits together with an epilogue and an index to form a three-part installation of the same title. In nearly three dozen stories, Issa uses just two names and virtually no adjectives to describe moments of connection, discord, humiliation, and hurt. The narratives are overwhelmingly nondescript, both archetypal and mundane. These are stories set in times of labor and leisure; at work and at home; in museums, libraries, schools, zoos, public gardens, city squares, and traffic-clogged streets. Again, the details have dropped out, leaving only a thin spine of experience and encounter.

Thirty-Three Stories is unlike anything else Issa has done before, but it reinforces the formalism of her triptychs, the process of deleting the details to explore the gaps left behind, and the notion of creating an artwork that is in dialogue with itself. “I’m trying to inhabit the position of looking at the work and not being the person who made it,” Issa says. “The forms of the stories — a museum lesson, a home school, a stranger’s house — the thing about these forms is that they rely on personal associations and memory. I’m trying to locate perceptions of difference and familiarity. There’s a danger in terms of what I want to do in that it’s not about personal healing. It’s about communication. I want these forms to speak and be responsible. I want to look in a removed way, attempt to solve a problem, and highlight a desire.”

To read back and forth across the enigmatic sequences that characterize Issa’s triptychs, monuments, and texts, you either fall into the hermetic system she has constructed to generate meaning, or you remain outside of it and whinge. One writer, responding to an artist’s talk Issa gave last year, complained: “These abstract forms… better reflect her own associations with the figures or events in question. Which is nice for her, of course, but for her audience the artwork remains a baffling network of elements whose actual meaning is unknowable.” That may say more about what the critic wants from the work than what he finds, but it also raises an important question about how (or when or why) art becomes useful and effective. Issa’s work doesn’t necessarily give you the tools you need to understand it, but it definitely leads you to a place where you can link things together on your own.

Not surprisingly, Issa maintains a detailed record of the history of her work on a neatly arranged website that features minimal black type and a lot of white space. One piece missing from the list, however, is The Revolutionary (2010), an audio work that was presented last year as part of the MENASA Studio Dispatches, a project organized for Art Dubai by the Island, an itinerant nonprofit that is nominally based in the UK. In Dubai, The Revolutionary was no more than an audio file with a set of headphones and an oversized beanbag plopped outside the entrance to the Art Park in Madinat Jumeirah.

To create the piece, Issa fed a long string of sentences through text-to-speech software to generate an unnervingly smooth account of a man who was everything and nothing. An eerily disembodied, vaguely aristocratic voice recites a jarring litany of observations about the character traits ascribed to a leader, rebel, believer, ideologue, and despot who was charismatic, distant, talkative, quiet, irrational, systematic, passionate, cold, judgmental, and influential. There isn’t a single proper noun in the entire text, just vague references to a cause, a sister, three books, and seventeen cities, among many other generic elements that repeatedly fail to make the story stick.

The Revolutionary is now parked on the Island’s website. One listens to the piece and fixates on the time bar sliding toward six minutes, as if the arrow were an anchor. Is Issa describing Che Guevara, Carlos the Jackal, Hassan Nasrallah? Some dictator recently deposed? Someone we know? She keeps you guessing; the language gains no traction, slipping between tabloid-style exposé and hard-core political history without revealing her sources or even a hint of whom she has in mind.

“He never cared if what he heard was true or false,” the tinny voice tells us, followed by the one and only quote attributed to Issa’s subject: “It is the rumors, the gossip, the lies, the made-up stories, the jokes and bitter expressions that truly interest me.” That line may be dressed up in the drama of pulp fiction, but the twist it orchestrates — from the historically or factually true to the personal or impressionable truly — could be an apt description for all of Issa’s work so far.