Liverpool

Susan Hefuna: Xcultural Codes

Bluecoat Arts Centre

May 29-July 17, 2004

In 2002 Susan Hefuna spent time in residence at Delfina Studios in London, a year in which she also exhibited in the capital. ‘Xcultural Codes’ run at Bluecoats Arts Centre, however, provided the first opportunity for UK audiences to see a substantial selection of work by this artist who seems to be constantly on the move. Born in 1962 into a mixed Muslim/Christian family, her father Egyptian, her mother German, Hefuna’s work reflects the sense of distance she feels both from Egypt where she grew up, and — significantly — from Germany, where she has spent much of her life and where she is based.

Whilst the experience of diaspora is one that is increasingly coming to signify, somewhat paradoxically, the idea of home at the start of the twenty-first century, Hefuna resists being pigeonholed as a ‘diasporic’ artist: “I think it is just normal that people are moving, moving all the time and mixing up. I am always on the move in the UK and US, in Europe. So my identity is a mixture of influences, which come from all over. I do not consider myself as anything.” Hefuna’s interest then lies in transcending labels, and in creating an art that is spiritual, timeless, open-ended, one that overcomes boundaries, categorization, and clichés.

To achieve this, however, she starts by visiting the very point from which those clichés emanate, interrogating codes and symbols already heavily invested with specific cultural associations, using images redolent of a time and a landscape scrutinized through an Imperial gaze. This is seen most clearly in her photographic series, which conjure up a distant world of colonial Egypt, scenes of everyday ordinariness made exotic by the presence of palm trees, a lone donkey tethered in the midday sun, or an intriguing doorway into some forbidden place. Elsewhere, Hefuna’s intricately patterned drawings suggest decoration from Middle Eastern or North African architecture, and her arcane sculptural objects seem to refer to Arabic antiquity. In these ways she constructs a fictive space, whose inauthenticity however is never far beneath the surface. Yet unlike cliché, in which meaning becomes devalued, reduced to perfect simplicity, this space is layered, ambiguous, open to multiple readings.

One could approach the same work in purely formal and aesthetic terms, from the same European modernist perspective that Hefuna’s fine-art training in Germany has equipped her with. But this interpretation alone ignores the cultural referents in Hefuna’s work, for example the significance of the mashrabiya (decorative wood carving used particularly in screens), with its position between private and public space, its metaphorical associations with veiling and voyeurism. Hefuna finds in the mashrabiya’s ability to operate in two directions the possibility for dialogue rather than closure, a template she uses for drawing in and engaging with her audience.

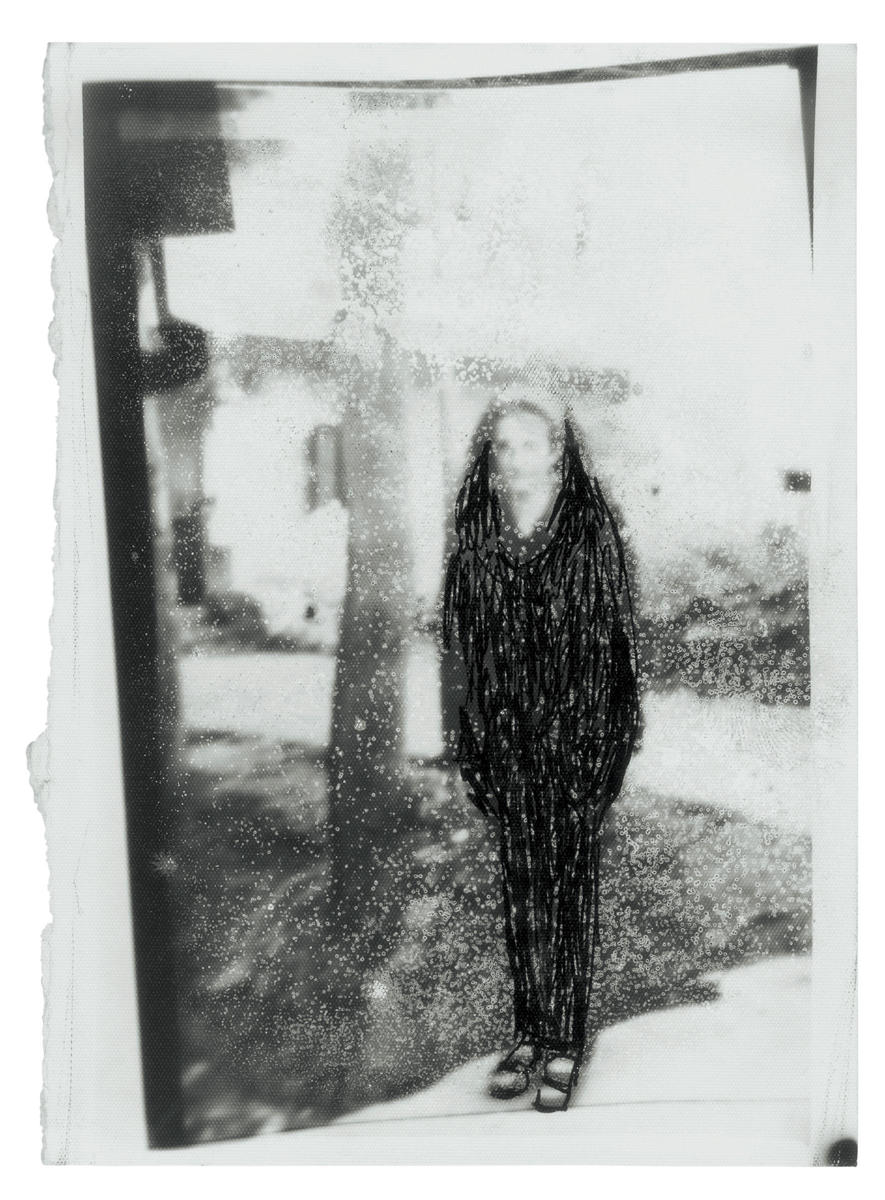

This is demonstrated in her photographic work, where there is an intangibility about the images that prompts questions from us rather than provides any immediate answers. These are photographs to ponder on, inviting the viewer to speculate on their production as much as on their content. Images of today’s Cairo appear grainy and rudimentary, as if created at a time when photography was in its infancy. Cityscapes are inexplicably printed in negative, whilst others taken of architectural detail on the streets of Cairo resemble the early darkroom experiments of Man Ray.

But nothing is as simple as it seems. Included among a set of picture postcards that Hefuna has produced, similar to ones that tourists send as greetings from Cairo, is one in which she sits in the lap of a sphinx statue, her serene inscrutability and arms outstretched in front of her mimicking the pose of her mythological host, as she watches the river flow. It is only on closer inspection that we realize it is the Thames she observes and the location is London’s Embankment, whose Cleopatra’s Needle obelisk is just out of shot. Hefuna’s impromptu intervention here is a small act of cultural reclamation, a simple yet effective gesture that decodes the monument’s symbolic presence right at the historical heart of Empire. The effect, as elsewhere in her work, is one of disorientation — literally, in the sense of Orientalism’s centuries-long indexing of the land to the east and south of the Mediterranean — as Hefuna steers us away from the certain paths that the West’s hegemonic compass has mapped out for the region.

The debt that European modernism, stretching back to Picasso and Matisse, owes to visual expressions from outside Europe has been well documented, if not fully embraced in official art histories. Islamic art in particular had a profound influence on artists in the West, demonstrating that the world could be pictured non-figuratively, and that patterning — up till then consigned to the category of mere decoration —offered possibilities for formal innovation (and indeed spiritual and philosophical signification). The coexistence in Hefuna’s practice of visual codes from both Islamic and Western conventions continues to interrogate this relationship, setting up an intriguing interplay.

The apparent simplicity of the lattice motifs in her drawings, for example, with their reference to the mashrabiya screen, belies the complexity of these graphic works. Gradually we notice flaws in the patterning, an irregularity to the lines, some of which discontinue and veer off course, and there is an imprecision to the joins. Far from either the rigorous mathematical order of classical Arabic pattern or the strict obsession of American contemporary artist Sol Lewitt’s grid drawings, Hefuna’s draftsmanship is intuitive, serving to loosen structural rigidity. Indeed this fluidity of line creates an impression of netting in these intimate works, rather than the solidity of the mashrabiya, which can — as Hefuna demonstrates in another series of digitally manipulated photographs — be dissolved through the effects of light and movement. Like net curtains, associated in an English context with the nosey neighbor forever lurking at the front window, keeping an eye on the comings and goings of the street, these lattices obscure what is behind them, sometimes a density of further patterned layers or else the shadow of an indistinct shape. We peer in, but are we too being observed?