The plan was to create an army of black “super children”: seventy boys and seventy girls who would flood into the United States from a secret compound in Canada to combat racial injustice and build a more perfect society from the bottom up. Lee Boyd Malvo, a seventeen-year-old immigrant from Kingston, Jamaica, was “very confident that this could be done,” his court-appointed psychologist reported.

But the plan required money — ten million dollars — and the best way to get it would be to hold the government hostage. Malvo and his partner, a forty-two-year-old Gulf War veteran named John Allen Muhammad, would kill six people at random each day for one month, sowing panic with random shootings in Washington, DC, and its affluent suburbs. Allen put a mattress in the back of his 1990 Chevy Caprice and carved a hole in the trunk, following the instructions for creating a “sniper’s nest” he had found in an old Irish Republican Army manual. If the money was not forthcoming, they would move on to Baltimore, where they would plant improvised explosive devices loaded with ball bearings among crowds of children. The government would pay them to stop; they would take the money, flee to Canada, and buy a plot of land. They would mold orphaned children into militants, providing weapons training and a revolutionary education, and when those children had become soldiers, they would be dispatched throughout the world to fight the enemies of black people and of Islam.

Over three weeks in October 2002, Malvo and Muhammad put the plan into action, killing ten people, critically injuring three others, and paralyzed the swath of strip malls and highway intersections that encompass the nation’s capital, before being caught asleep in their car at a rest stop near Myersville, Maryland. Malvo was supposed to have been acting as lookout but had nodded off.

“We had a strategy from the beginning,” Malvo said in his initial confession. “You keep your enemy fortified. You stretch them out and make them weak.” If the police didn’t catch them and the government refused to pay them, they would keep killing until the authorities were forced to declare martial law. “Bringing the military in,” Malvo said, “would tear this side of the country up with the economy, tear this whole faction up. Tear this whole section of the country up.”

Later, he changed his story. Malvo said that he cried after Muhammad laid out the plan and demanded his compliance. He sat alone in a bathroom playing Russian roulette with a 22-caliber revolver. “I loaded one round, spun it, put it to my head, fired,” he said. Nothing happened. “I broke down and couldn’t do it.”

Malvo learned to be obedient at a young age. He was born in the slums of Kingston in February 1985, the son of Leslie Malvo, a construction worker, and Una James, a seamstress. Leslie worked off-island and, according to Carmeta Albarus-Lindo, the psychologist who examined Malvo after his arrest, the boy was “inconsolable” during his father’s long absences. But his mother suspected Leslie of having an affair, and one morning in the spring of 1990, James woke her son and told him to pack some bags. By the afternoon, they were on a bus to Endeavor, a small mountain town near the west coast of the island. James didn’t tell Leslie where they had gone, and he didn’t come after them.

In Endeavor, James left her son with friends and neighbors for weeks on end while she searched for odd jobs in nearby towns, though she never seemed to return with much money. When she did come home, she would spend what little she had on booze and install herself in front of the television; Malvo would wander in circles around their modest home and scream for his father until she came out and lashed his bare back with a belt. James would become enraged if she asked Malvo to bring her a basket and he brought it too slowly, throwing shoes at him and pulling his hair. The boy gradually retreated inward, speaking less and less. Diane Schetky, a psychiatrist who also served as an expert witness on his behalf, considered this a pivotal moment: “Lee responded to the abuse by being compliant. He learned that if he put himself in a trance, the punishment didn’t hurt as much.”

Things were tough in Endeavor, and when Malvo was twelve, James moved them again, this time to Antigua, where they lived in a shack without electricity or running water. James began leaving her son for months at a time; when she came back, he would sometimes threaten to kill himself, and she would whip him in response. (Later, Leslie Malvo called her “a good mother sometimes and a bad mother at other times.”) Eventually he stopped making threats. Once, James disappeared for eight months without sending money or telling her son when or if she planned to return. Malvo supported himself by begging and scavenging for scraps of metal and salvaging electronics, which he would sell on the street.

Before his trial, Malvo told Albarus-Lindo about something that had happened when he was in Kingston. While walking to school one day, he saw a man shot to death on the other side of the street. One of the gunmen caught Malvo’s eye and waved the boy away with his pistol, while his partner searched the dead man’s body. Malvo walked away as directed.

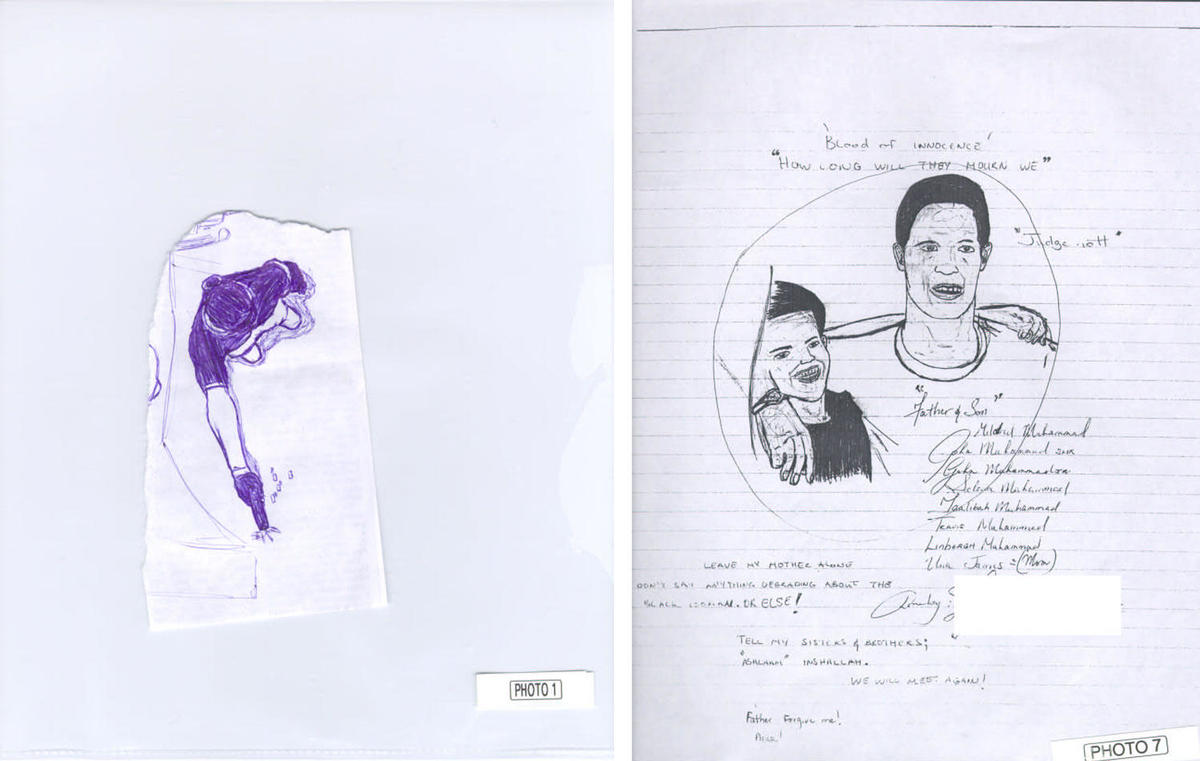

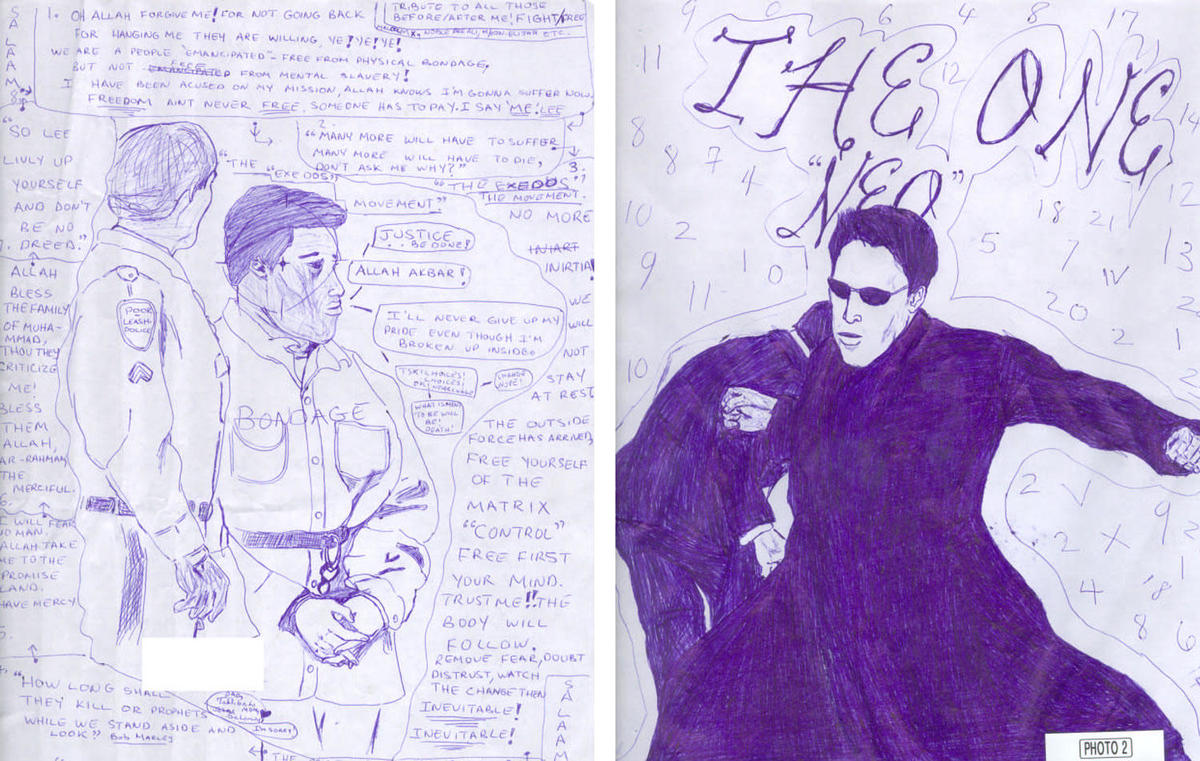

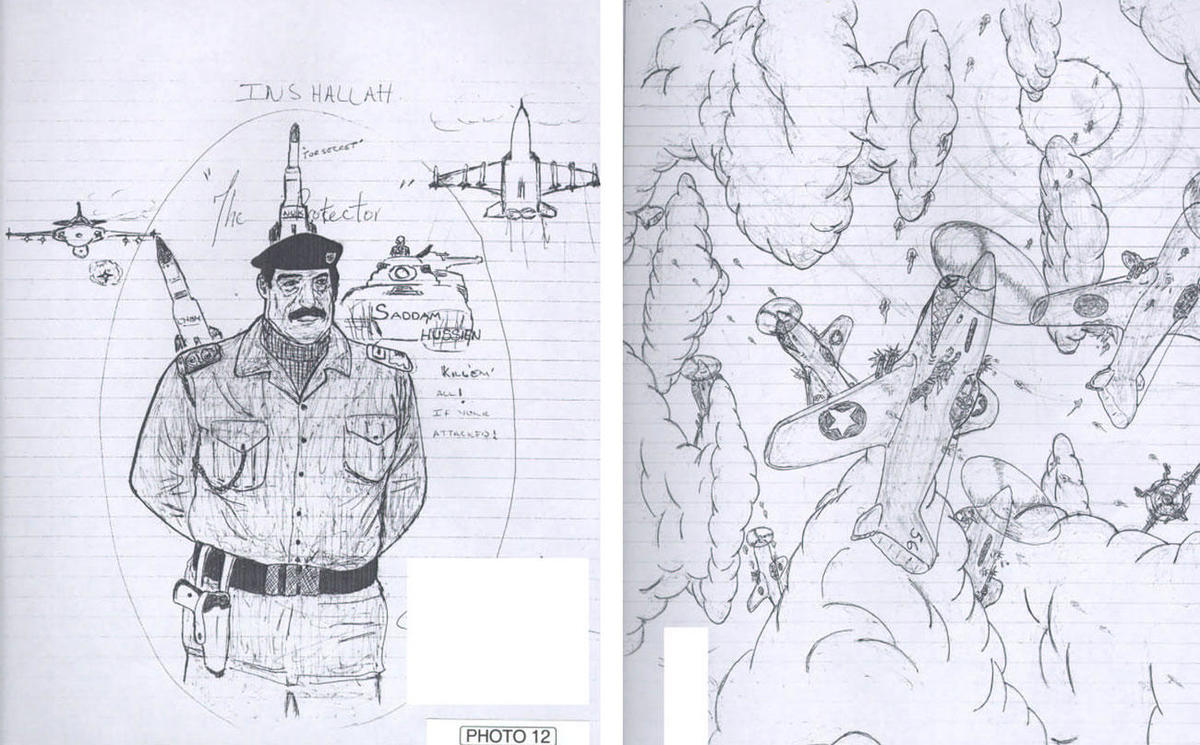

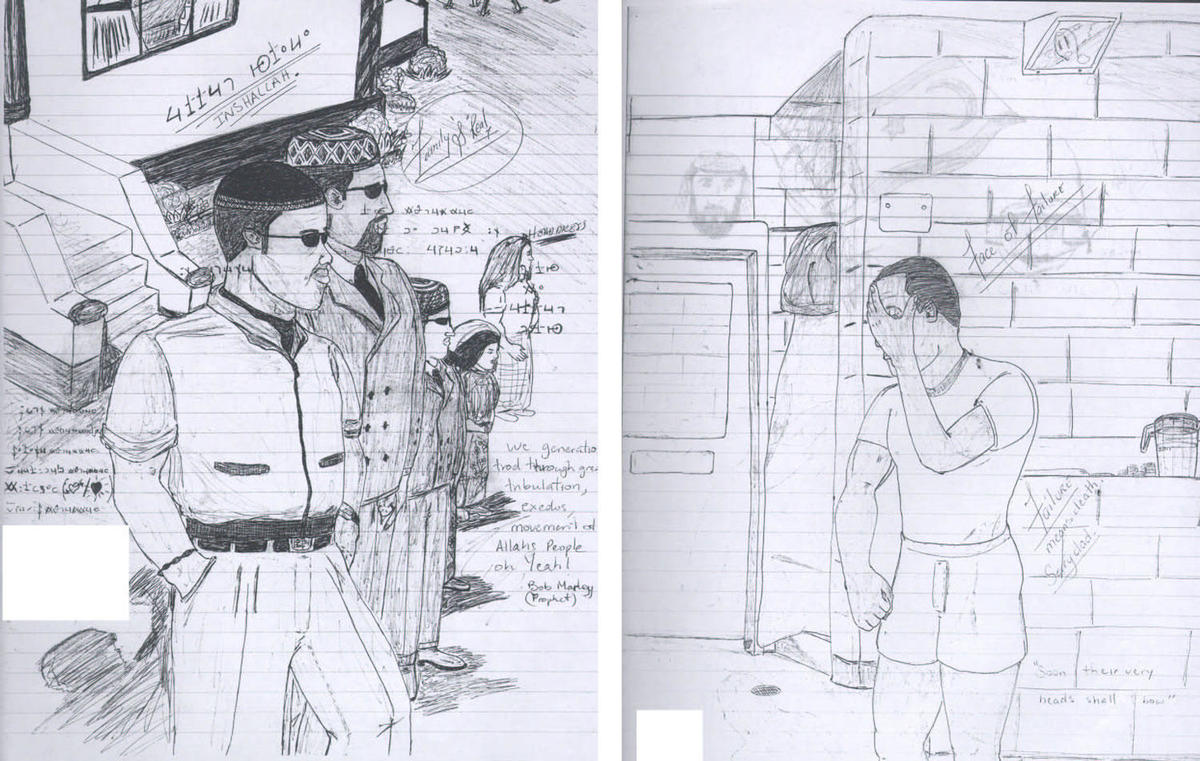

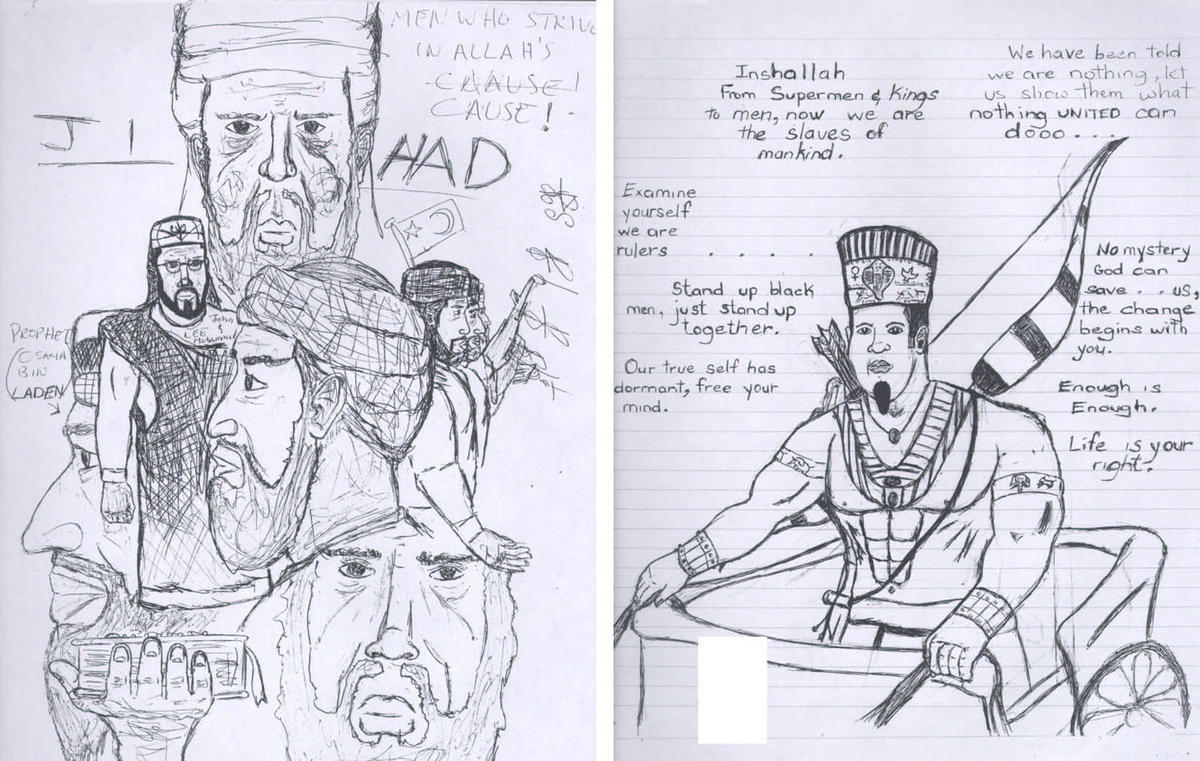

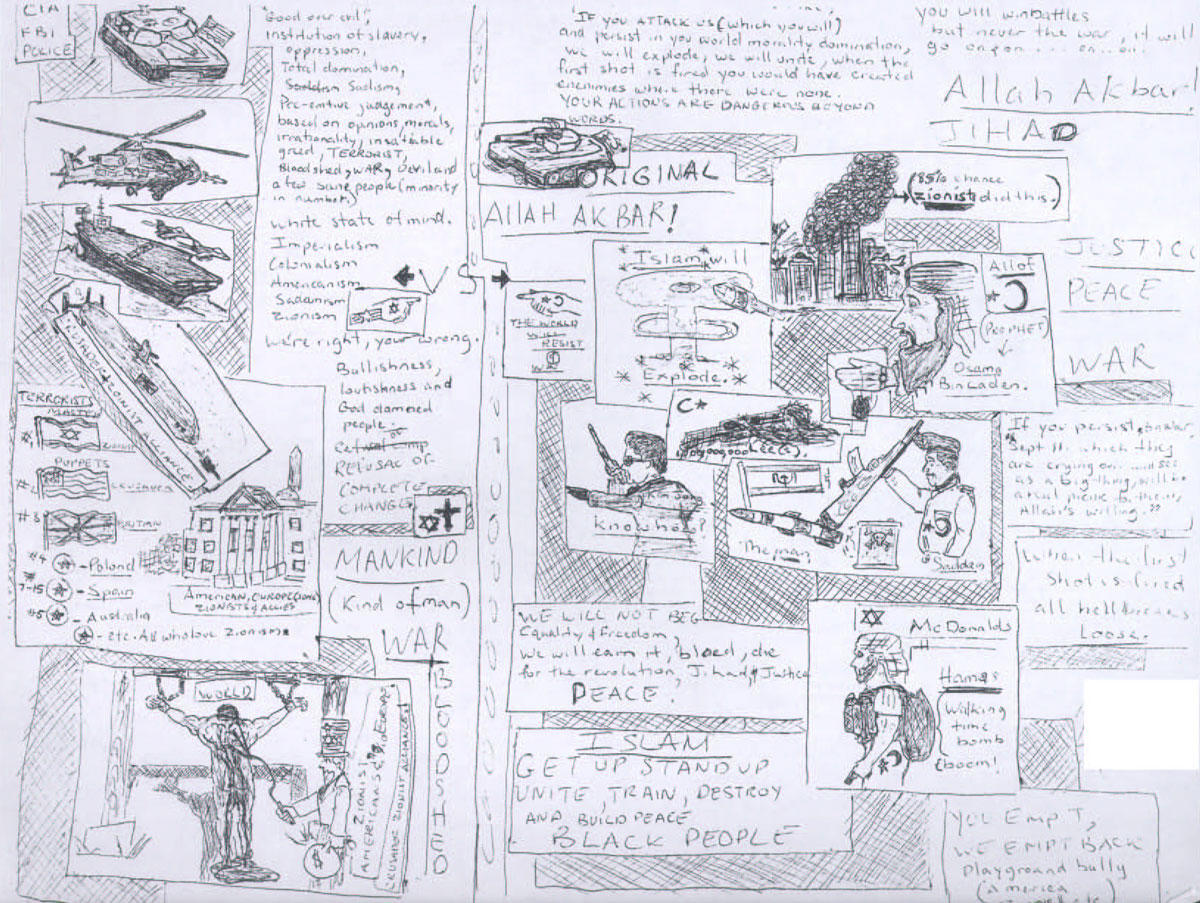

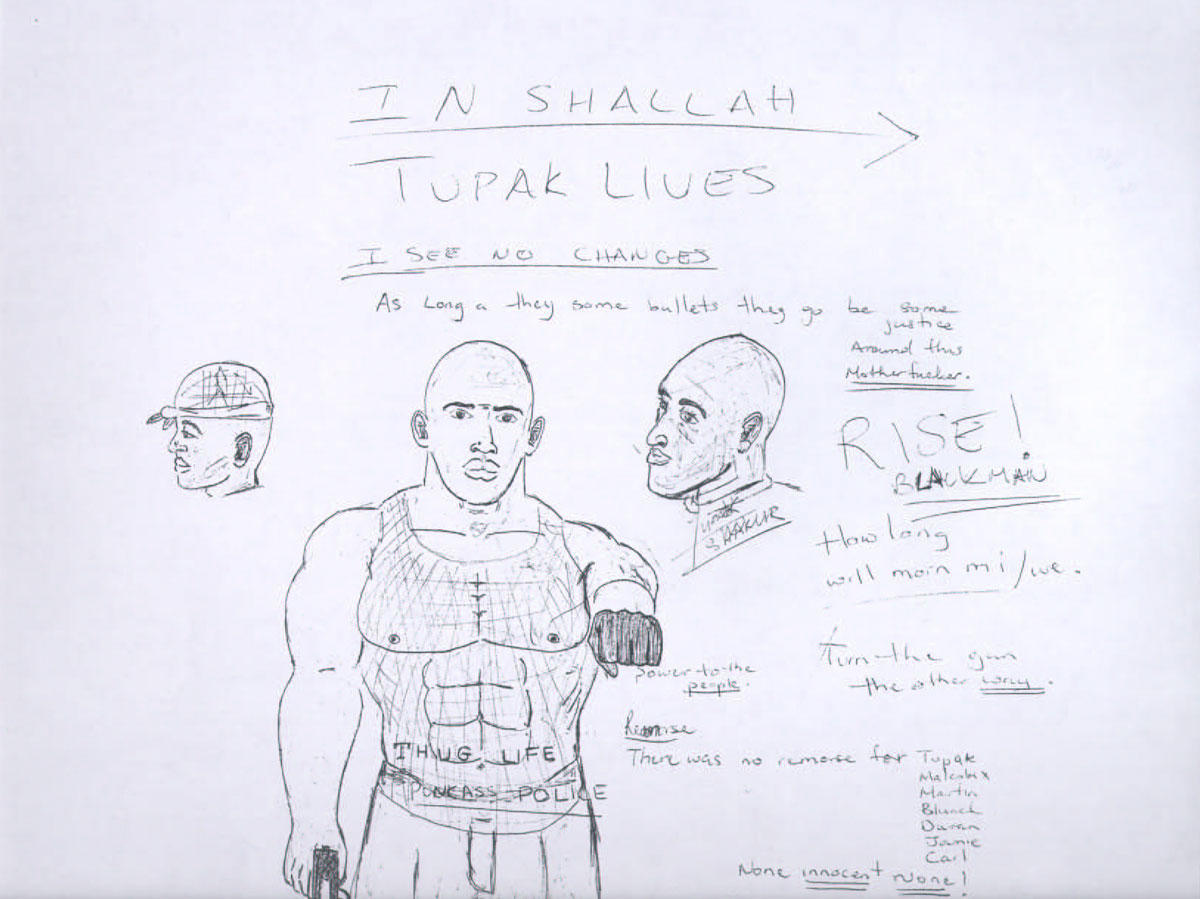

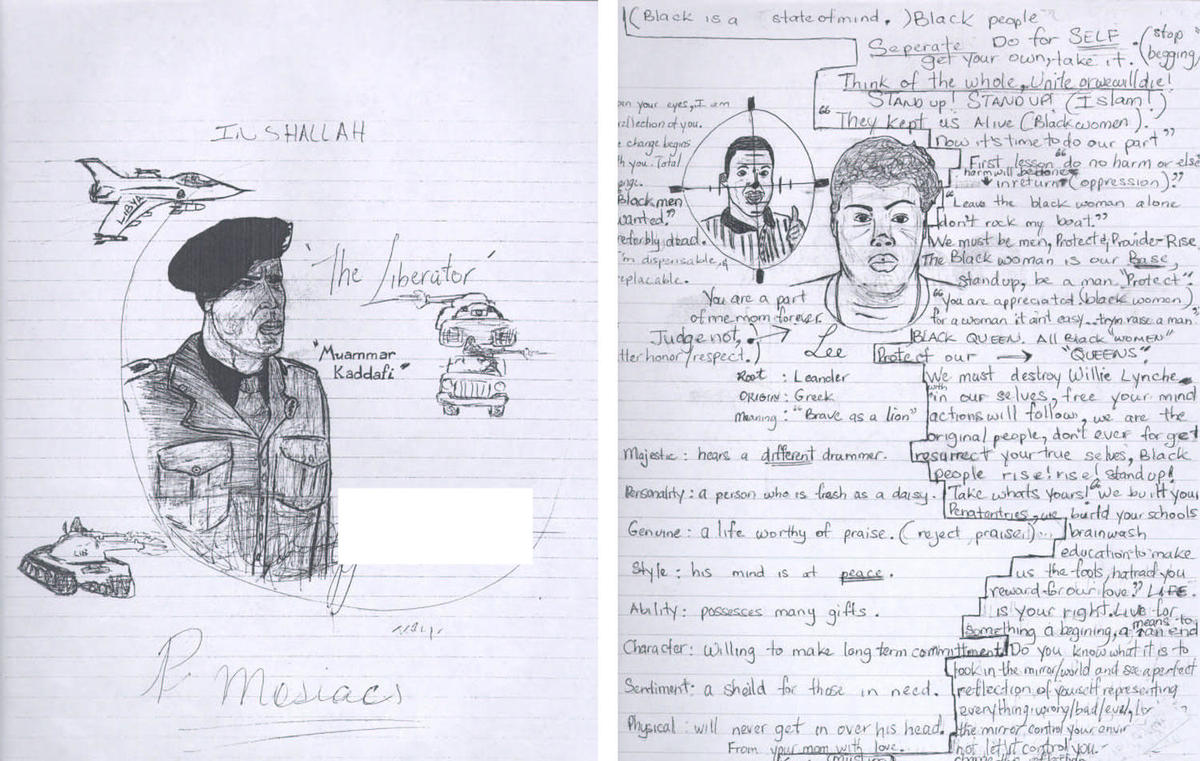

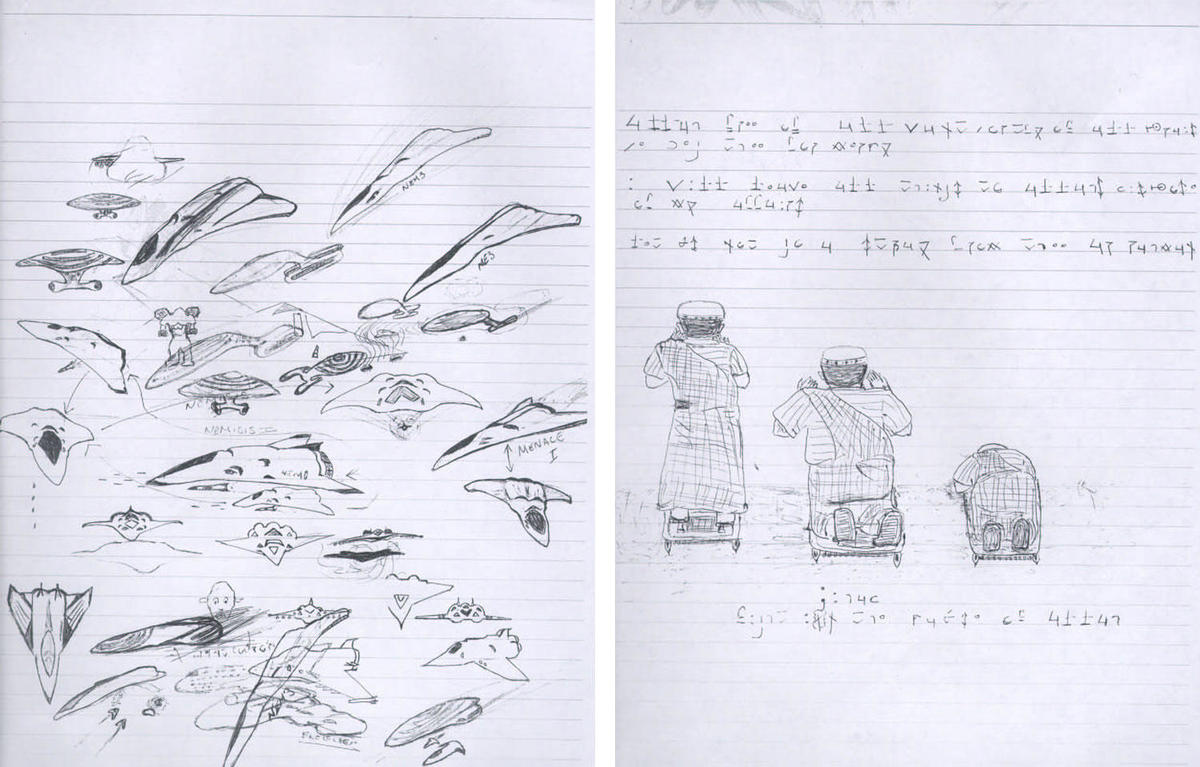

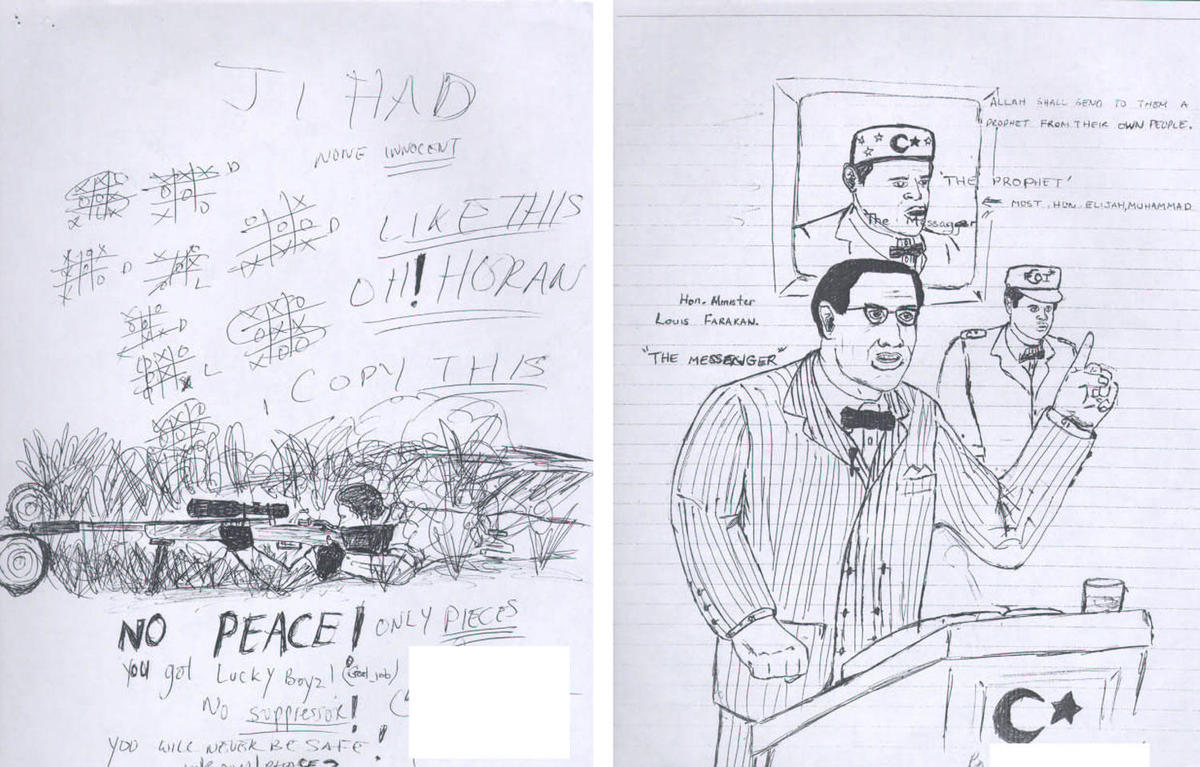

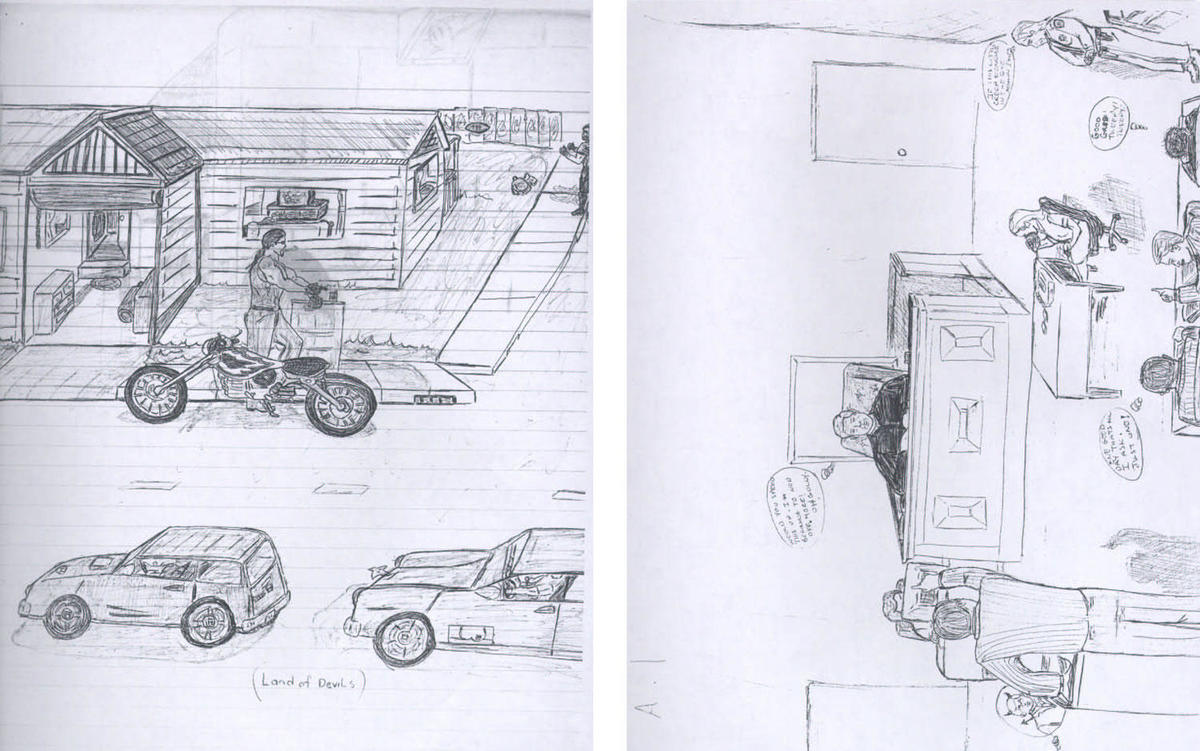

In prison and in the courtroom, Malvo made drawings and penned political tracts on pieces of paper torn from the legal pads provided by his counsel. Nearly a hundred of these pages were found in his cell between January and March of 2003. The pages are populated by characters ranging from Tupac to Hannibal, Osama Bin Laden to Charlie Brown, Trent Lott to Marcus Garvey. They reflect two years of indoctrination from Muhammad and a mind abraded by a lifetime of hardship and deprivation, but they also reveal the stirrings of an imagination much like that of any teenager living in America in the first years of the twenty-first century.

During the trial, Malvo could often be seen in a baggy crewneck sweater, slumped over the defense table, sketching satirical tableaux of the proceedings that depicted all participants as detached, disinterested, or preoccupied with wayward thoughts. In one picture, a lawyer tries to convince the jury of Malvo’s innocence, while reflecting, “On the other hand, he is a lunatic.” Another lawyer looks on, thinking, “I can’t believe this crazy boy wants to die! Not on my watch.”

Meanwhile, Malvo’s avatar whistles and dreams of basketball. “GOOD GRIEF! I gotta sit here and look pretty,” reads one thought bubble. Next to it, a comically inflated Malvo palms a basketball and glides toward the rim in a Michael Jordan pose, his cumbrous sneakers dusting another player’s bald head. A second thought bubble emerges from that scene, a line from a revolutionary ballad by the Steve Miller Band: “Time keeps on slipping into… future. I’m gonna flyyy! Oh yeah!” Three lines dominate the page:

PRETEND COURT

WHACK ME GET IT OVER WITH

GOSH!

In another drawing, a retinue of lawyers confer before the judge, one draping his arm over another’s shoulder. Above their heads, Malvo has identified them as “the guys who wanna save my life. Ha! Ha!” Beneath the scene, seemingly as an afterthought: “Allah is the disposer of my affairs!”

In Antigua, Una James was selling cold drinks outside a bus station, and a friend recommended she see Muhammad about procuring fake documents that would allow her to emigrate. Muhammad had recently moved to the island with his own three children after divorcing his second wife. He and James became friendly, and he immediately took an interest in Malvo, who would often stay at his house. Muhammad taught him about Islam and the oppression of black people; the fifteen-year-old adopted the man’s American accent and began calling him “father.” The two lifted weights and played basketball together.

When James went to find work in Florida, she left Malvo with Muhammad. The two snuck into Miami to join her briefly in 2001, but then took a bus across the country to Bellingham, Washington, where they registered at the Lighthouse Mission shelter as father and son. They got a family membership at the YMCA, and Malvo enrolled in a local high school. Lee’s classmates later claimed that he did well in school, though he didn’t make any friends.

Muhammad had Malvo steal a 223-caliber Bushmaster AR15 rifle from a local gun shop and began subjecting the boy to a rigorous training program: leopard-crawls across the forest floor, calisthenics, revolutionary literature, target practice, and military theory. Each night before he went to bed, Malvo was made to memorize passages from Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. Often the pair would drive deep into the stands of white oak and Douglas-fir to practice marksmanship, using makeshift targets with paper plates for heads. Other times Muhammad would tie Malvo up for hours in the brumous foothills of Mount Baker, where he would go without food, water, or sleep until the older man came back to free him.

There were also video games, predominantly first-person shooters; Malvo’s lawyers later suggested that these inured him to senseless killing and to the prospect of his own death. “If you get hit, you bleed and you die, unless you hit a particular code,” said one attorney, Craig Cooley. “Most of these games have a code where you become invincible, where you become immortal. Game players call it the God mode. When you punch that in on some of those games, it says, ‘I am God.’” Cooley went on to compare the boy to the American soldiers brainwashed by the Chinese during the Korean War.

At his own trial, Muhammad refused representation. When it was time to cross-examine Malvo, Muhammad stood shackled behind the defense table, clutching several sheets of lined yellow paper in his left hand.

“The last time we played basketball, who won?”

“You won.”

“The last time we ran a mile, who ran faster?”

“You.”

“And the last time we ran five miles, who ran faster?”

“You did.”

On December 8, 2003, Malvo’s lawyers showed jurors a particularly violent ten-minute clip of The Matrix. The jurors were informed that Malvo had watched the film over a hundred times, “to prepare his mind for what was going to lie ahead.” Malvo identified with the hero, Neo. Muhammad was his Morpheus — a father figure who chooses a young man to “lead a revolution against an evil government that has people oppressed to the point where they don’t even know they’re oppressed.” The goal of their mission had been to foster “massive societal change.”

“The Matrix is interesting,” CNN reported, “because they think that all of reality is a lie, and that there was no right and wrong, that the government — because the government is a lie, and maybe he seemed to be living in that world, and was searching for a way out of it.”

One of Malvo’s drawings depicts him in handcuffs, the word “bondage” etched across the baroque musculature of his chest. “The outside force has arrived, free yourself of the Matrix 'control,’” the text reads. “Free first your mind. Trust me!! The body will follow.” Malvo’s prison drawings inspired his interpreter, Albarus-Lindo, to this conjecture:

When Lee began to think that he was destined to remain a child forever, that he could never do without protection against strange powers, he lent those powers the features belonging to the figure of his father. He created for himself the gods whom he dreaded, whom he sought to propitiate, and whom he nevertheless entrusted with his own protection. It seems to me that his longing for a father is a motive identical with his need for protection against the consequences of his human weakness.

Malvo put it more simply. “I was desperate to fill a void in my life, and I was ready to give my life for him.”

In one picture, Lee drew a gallant lion with a heavy, wind-swept mane. It appears to be striding from the right side of the page to the left, its snout leading the way. The lion occupies the bottom third of the page, and above it Lee wrote the following:

Lee

Root: Leander

Origin: Greek

Meaning: brave as a lion

Majestic: hears a different drummer.

Personality: a person who is fresh as a daisy.

Genuine: a life worthy of praise (needs no admonition, give to Allah.)

Style: his mind is at peace

Ability: possesses many gifts.

Character: willing to make long-term commitment

Sentiment: a shield for those in need.

Physical: will never get in over his head.

Alongside the lion, Lee copied some verses of a traditional folk song made famous by Recep Tayyip Erdogan, now Turkey’s prime minister, who had been arrested for uttering them in public in 1999. “Our minarets are our bayonets / Our mosques are our barracks / Our believers are our soldiers.”

“I planned to shoot him in the head,” said the voice on the tape. “Circumstances didn’t allow me to shoot him in the head. He was bobbing.” The voice was casually frustrated, as if recounting a trip to the beach that had been marred by inclement weather. What it was actually describing was a man standing in the pale suburban light of a Ponderosa Steakhouse parking lot as his would-be assassin waited for his shot from the trunk of a Chevy Caprice.

In the courtroom, Lee listened to the voice play back. His voice. He quit drawing, pushed his legal pad aside. His eyes winced with recognition, and he arched his back and lowered his head with the mechanical slowness of a twenty-ton crane until his temple touched the counsel’s table. The arc of prayer, one commentator noticed.

It was the evening of October 19, 2002. As Stephanie Hooper testified, she and her husband Jeffrey had just finished “a very nice dinner” at one of the many Ponderosa Steakhouse locations that cling to the length of I-95 connecting Washington, DC, and Richmond, Virginia. They were on their way home to Melbourne, Florida, after visiting family in Pennsylvania. On account of the snipers, they had circumvented DC as best they could. Now, just north of Richmond, they had finally managed to forget about the news reports and enjoy “some wonderful conversation.” She remembered arguing with her husband as they exited the restaurant — about “who loved each other more.” They held hands on the way to the curb. Before they went to their separate sides of the car, Jeffrey pulled Stephanie close and pressed his lips against hers, and then a bullet tore through his skin and tunneled into his gut.

“I thought it important to lie down,” he remembered, “so I lied down on the pavement there.” He told Stephanie he loved her, and they prayed together, with Stephanie still holding two cookies left over from dessert.

In one drawing, Hannibal Barca, the legendary military commander who led the Carthaginians over the Pyrenees in the Second Punic War, plunges a sword into the chest of a felled “white man/devil”; in another, he bares his rock-hard chest and stares straight ahead. Below his figure, the slogan “We will either find a way, or make one.”

In another, Malvo is crouching close to the ground, arms wrapped around an oversize rifle, eyes trained on an unseen target, the words “Jihad” and “none innocent” and “No peace!” hanging above him. On one corner of the page there are eight games of tic-tac-toe he must have played to pass time during the trial.

Elsewhere, there is a self-portrait: Lee as an ancient African king, decked out in beads and chains, steering a chariot. There are figures from comics and video games, including one with drills for hands and a crescent emblazoned across his chest. There is a character from Street Fighter and an elfin archer straight out of The Lord of the Rings. There is a portrait of Tupac with his right hand gripping a pistol and his left fist extended toward the viewer, anticipating a bump. Inscribed above, “Inshallah, Tupak lives. I see no changes.” The left half of one page is crowded with images of American aircraft carriers, tanks, and helicopters, alongside a list of the country’s traits: “White state of mind. Imperialism. Colonialism. Americanism. Zionism. Sadism. Bullishness. Loutishness and God damned people.” At the bottom of the page, a naked black man stands manacled to a whipping post, Uncle Sam lashing him with one hand and hoisting a sack of money with the other. (“The world is diverse for a reason, people will forever have their own morals and opinions…. If you the majority would travel and do more research, then you would see the affect of American foreign policy…”) On the right half are sketches of Bin Laden, a mushroom cloud, the World Trade Center attacks, a McDonald’s with a Star of David on its facade; “Jihad, Justice, PEACE.”

“You’ve Willie Lynchized us,” he scrawled on another page, moving from cursive to script and back again. “Black people must stand up as one, must be kings”; “Stop begging, get your own, take it”; “Think of the whole, Unite or we will die!”; “Stand Up! Stand Up! (Islam!)”; “Free your mind!”; “Tupak calls them punch ass police. Me too! (Police→poor-leash).” And: “Failure means death. Sorry dad.”

“Hey and just to let you know even if you read this I know you won’t change, because change is complete not partial, and time doesn’t change a thing, time hasn’t changed you. You are the same white man, you have just toned down your opinions, but your actions speak loudly—same old ideology (Trent Lott). (We should separate.)” “Lee, weren’t they innocent?” “An object (the rich whites) at rest stays at rest until moved by an outside force.” “'Many more will have to suffer many more will have to die, don’t ask me why’ Natural mystic (Prophet Bob Marley).” “We must be like nature… when she unleashes a force it is complete, impartial and constant.”

Also, a five-panel cartoon titled “What dogs do when you go to work.”

The Malvo case was a shock, a sensation, not an event that altered the life of the country, nor one that had much to say about it. As the effect wore off, as the plot was revealed to be the work of a deranged man and a screwed-up kid, our flitting attention moved elsewhere. Now, there are the Michelle Malkin blog entries preserved as if caked in ash, the increasingly dutiful Court TV reports, the images of the victims’ faces arranged in a perfect grid courtesy of the Washington Post.

And the journals. The first thing I thought of when I saw Malvo’s letters and drawings in news reports were my own high-school journals. As a teenager in Tucson, Arizona, I had carried around a couple of beat-up leather-bound notebooks as a point of pride, casually deploying them in coffee shops, at shows, and between classes. I filled them with what are surely some of the most contrived attempts at poetry ever committed to paper; caricatures of disciplinarian teachers and loathsome politicians (I reserved particular opprobrium for Tipper Gore and a school administrator named Ms. Shackman, who had suspended me for throwing a seatbelt buckle out the bus window, hitting a pedestrian); the logos and lyrics of punk and hardcore bands and lines from Beat poets; paeans to whichever dissident I had pledged allegiance to that month.

My sophomore year, every student in Writing in Society class was required to make a “commonplace book,” which the teacher described as “a place for your thoughts and dreams and frustrations and reflections, a place where your mind can live free.” I remember one girl presenting her book two weeks later: it was already full, an accordion of Polaroids, dried flowers, movie tickets, magazine clippings, feathers, locks of hair, friendship bracelets, notes passed in class. I remember asking during her presentation if there was anything from the previous two weeks that she had not put in her commonplace book, and relishing the laughter that ensued.

For my part, I cut out pages from skateboarding magazines, pasted in photocopied fliers, excised slogans from pamphlets distributed at meetings of the University of Arizona’s Young Marxists club, which I had been attending with considerable pride and overwhelming confusion. (I quit after I learned that the leaders were planning on dropping out of school to get factory jobs and “agitate from the inside.” That was too much for me.) After the school day ended, my Spanish teacher, an old Marxist, donned a skullcap woven by an indigenous community in the Bolivian Andes and opened his library of radical literature to about fifteen of us who were hoping to find some set of data or gestures or symbols — anything, really — with which to identify ourselves before high school passed us by and we were marooned. The day before, we had chosen an acronym for ourselves and gathered for a two-hour lecture on The Communist Manifesto. I remember our class “free write” that day, and the mess that came out of it: the workers having nothing to lose but their chains, the I-Ching having everything to teach us; choice lines from Dead Prez, the Dead Kennedys, Leonard Peltier, and Jack Kerouac, all alloyed with my own substantial sexual and social frustrations. The pages teemed with vague feelings of injustice perpetrated by everyone from my parents to the school’s principal to Newt Gingrich, such that an upside-down American flag and a Bad Brains lyric somehow qualified as a response to one of the teacher’s prompts: in Richard Wright’s Native Son (which we had just finished reading) what led Bigger Thomas to kill Mary Dalton?

Malvo’s letters and drawings didn’t seem crazy to me. They still don’t. The more I look at them, the more typical they appear: the teenager’s attempt to work through complex questions about the way the world is and the way it should be. This, before one has the proper tools to find sufficient answers, at a time when parental authority is anathema but guidance is essential; perhaps most importantly, before such questions become so familiar as to no longer seem insistent, or even to register. Malvo, I thought, was enchanted by the world and battered by it, as I was, as most teenagers are.

Albarus-Lindo said of Lee, “I recognized something was amiss with this Jamaican boy who had not been in this country three years and is speaking as if he had lived here his whole life and suffered years of social injustice.” But this is life as a teenager. The world seems infinitely strange, seems to be constantly eluding your grasp, thwarting your attempts to comprehend it, much less inhabit it. For Malvo, circumstances turned these more or less natural feelings into something deeply pathological; the outside world became a mere projection of his inner life, with Muhammad as its architect, creating order and purpose where there had been none.

Malvo is currently serving a life term in Virginia’s Red Onion State Prison, a maximum-security facility where he spends twenty-three hours a day in his cell. Shortly before being sentenced, he wrote a note anticipating the death penalty: “I think I’ve said enough… to fill a tiring ear so! Long! But The Change begins with you!… I’ll be back and next time whatsoever my endeavor is ‘I will not fail.’ You control your environment don’t let it control you…. Change! You have a CHOICE! You CHOOSE TO BE CONTROLLED! FREE YOUR MIND!” But after four years in prison, a world more fixed and, in many ways, less perplexing than any Lee had experienced, he had resigned himself to that control, put his mind — and his pen — to rest.

One day he made a phone call to Cheryll Witz. He and Muhammad had killed Cheryll’s father, Jerry, on March 19, 2002, as he hit chip shots on the practice green at the Fred Enke Golf Course in Tucson. It had been a test run for the shootings in DC. Cheryll, a large woman in her mid-forties with sheer curls of blond hair, was shopping for a birthday cake at Costco with her best friend at the time, and she picked up her cellphone after three rings. Lee introduced himself and told her he wanted to apologize. “I tried to write a letter,” he told her, fighting back tears. “But I couldn’t. I didn’t know what to say.”