As a kid in Saginaw, Michigan, I used to work in the family business, an Army-Navy store. Over time the store went from selling military surplus from the Vietnam war to just about everything you’d find in a department store — from foam rubber and spray mace (the canister was labeled “Chemical Weapon”) to Italian stilettos.

My dad acquired a box of portable radios when I was eight, from a Lebanese dealer down in Detroit, a family friend on my mother’s side. I already had a transistor radio, and my parents had a large tabletop hi-fi, but these were different. These brightly colored radios were about the size of a shoebox, and they had multichannel settings for weather, police, and shortwave bands. The shortwave bands had strange titles — “world,” “maritime,” and “tropical” — and I obsessed over the idea of receiving stations from beyond Saginaw. What little I could pick up on the shortwave, though, was limited to the BBC, Radio China, and the Voice of America’s overseas network—mostly news.

It was on a sultry evening in Marbella, Spain, on a hotel balcony, that I first tuned in to Radio Tangier International. I was twenty-four, and it was my first extended trip abroad. My baggage consisted of a change of clothes, a cheap alto saxophone, a notebook, and a shortwave with a built-in cassette recorder. The first three tracks I heard were by Farid al-Atrache, R. D. Burman, and Miles Davis. This was everything I’d daydreamed about as a kid, without knowing it: a radio station mixing bebop, Arab pop music, and Indian film soundtracks. I started making tapes.

At first the idea was just to document what I was hearing, with the idea of perhaps incorporating some “found sounds” into my own music. But I became fascinated by the juxtaposition of languages and the diversity of audio possibilities. I started recording commercials, DJ bumpers, and other non-musical miscellany: frequency jamming, station IDs, and shards of pure white noise, along with peripheral rhythmic static. Three weeks after arriving in Spain, I was on a boat to Morocco, where I kept at it for two and a half months. I came home with twenty hours of tapes.

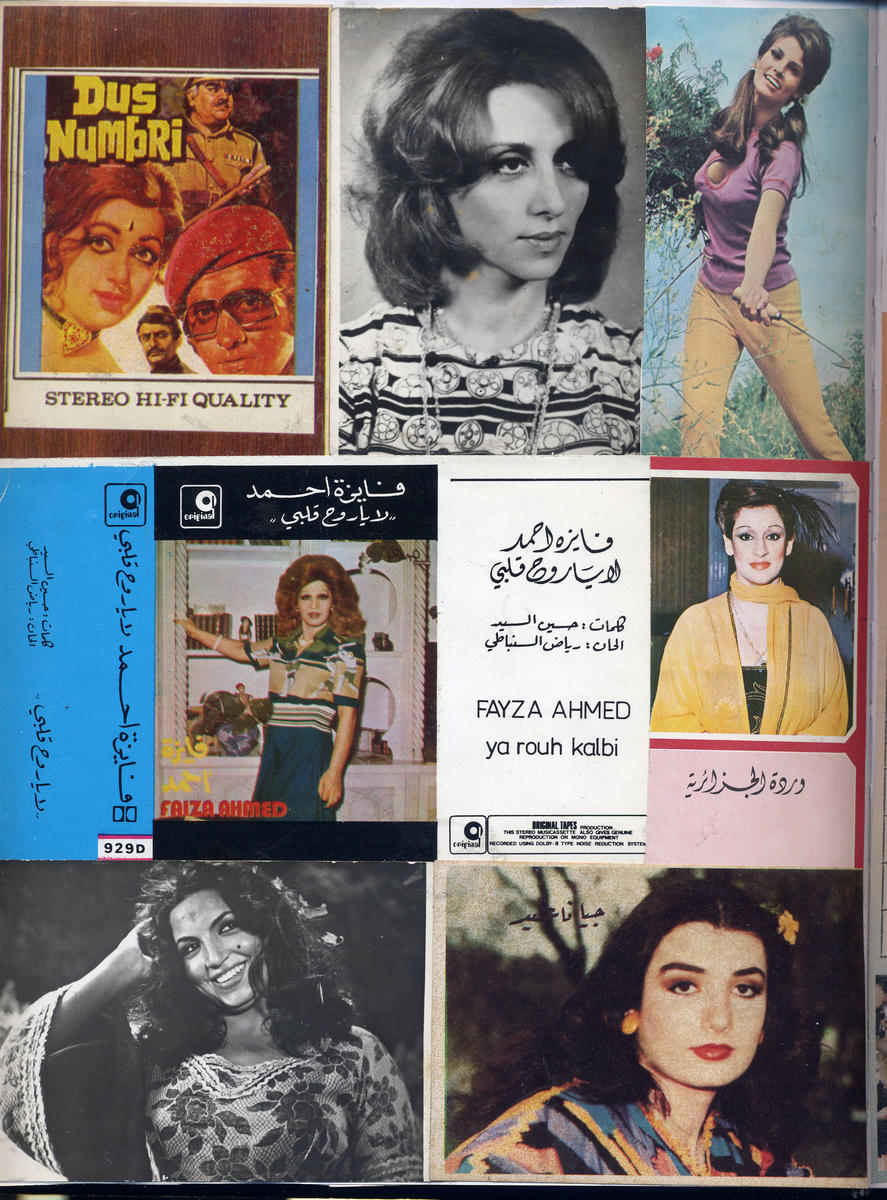

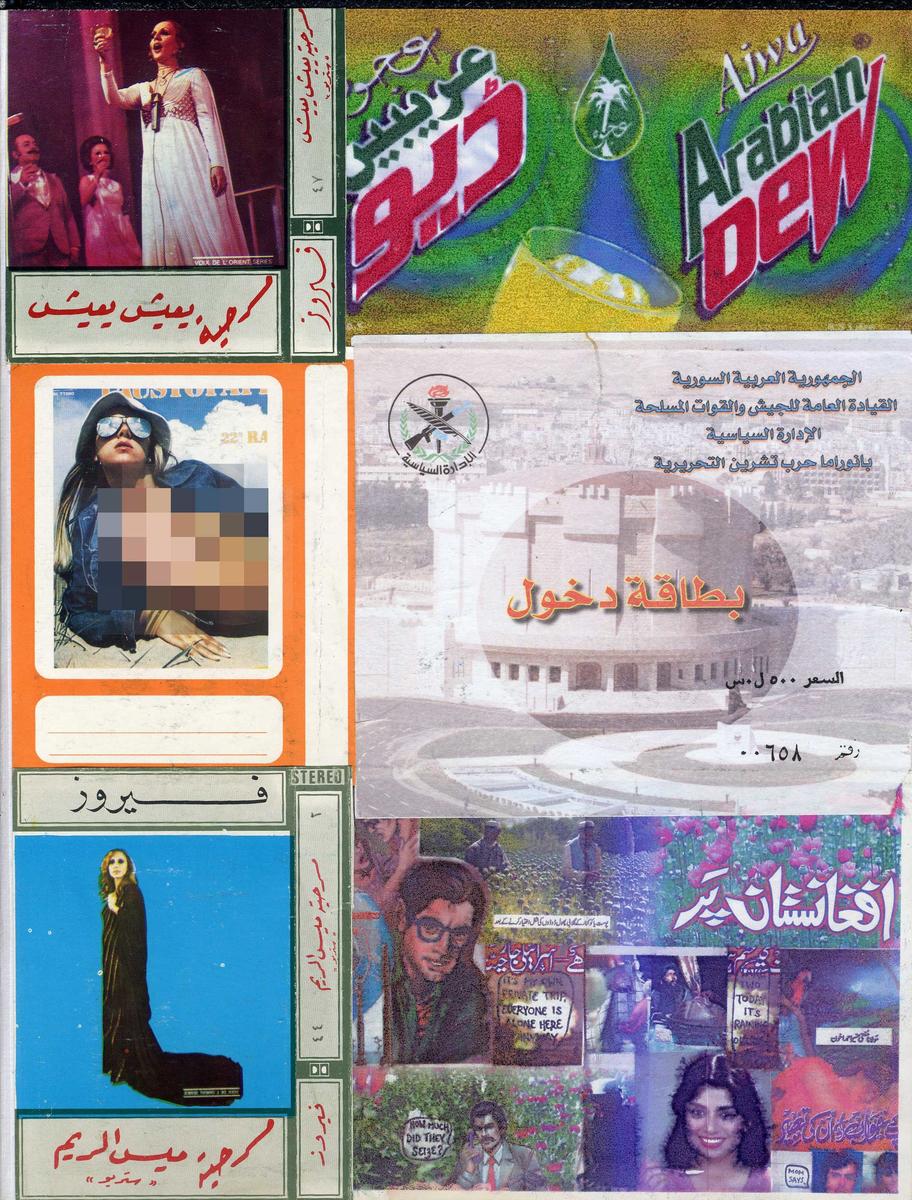

In Morocco I also played with local musicians and recorded those sessions; wrote stories, songs, and poems; and collected local cassettes. I was traveling on a shoestring and had nothing but time on my hands as I drifted from town to town. It was in places like Tétuan, Fes, Essaouira, and Marrakesh that I discovered the template for what would eventually become one of my life’s works: locating, documenting, and collecting music from well beyond Saginaw, wherever the culture interested me — primarily North Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia.

Back in the States, with access to multiple cassette decks, I began assembling sequences from my radio sessions into an audio collage. Elements from that tape began making their way into Sun City Girls songs. Many years later, when a friend and I started the Sublime Frequencies label, one of our earliest releases was Radio Morocco, that first radio collage I’d made back in 1984.

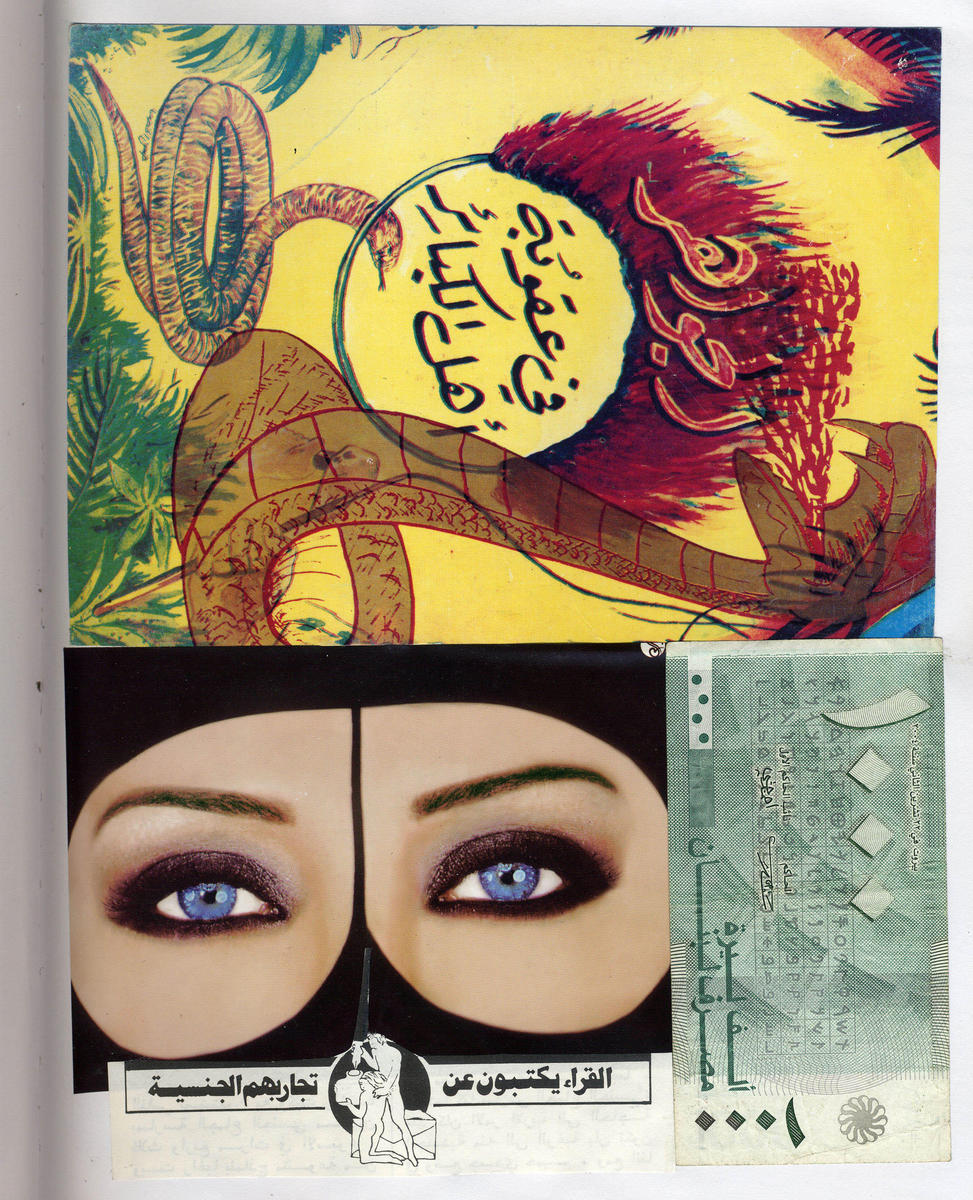

Recording and collaging radio broadcasts became an inseparable part of traveling. A similar impulse led me to create books. Anytime I go anywhere I cram all my ideas onto blank pages. Sometimes the end result is primarily text; sometimes, combinations of found images. Some of them are elaborate and flamboyant; others, quite simple and modest. There are fifty-four of them now, going back twenty-five years, and each remains fully intact and in place, ready to confound any who may care to experience them in the future. Sometimes friends suggest that I publish them or do a gallery show or find some other way to get them out there. But I actually like the idea of digging a hole somewhere and burying my library of unique artifacts. Besides, I have no idea what I’m doing, and I’d prefer to keep it that way.