The 1966 film Poppies Are Also Flowers is an international crime thriller that follows the trafficking of opium from the fields of Iran to the mafia distributors of Europe. Sponsored by the United Nations and shot on location for American audiences, it apparently was intended to raise awareness about the complexity of the global drug trade and the UN’s role in stopping it. Despite being written by Ian Fleming and featuring a surprising number of stars — including Angie Dickinson, Rita Hayworth, Trevor Howard, Omar Sharif, the Princess Grace, and of course, Yul Brynner — the film quickly faded from cultural memory.

In Poppies, Brynner plays Colonel Salem, an Iranian army colonel working alongside the UN. His role is to find the source of a poppy trail deep in the mountains of Iran. Disguised as a tribal leader on horseback with a black fur fez, and backed by a small number of men, Colonel Salem and his party encounter a real tribal gang looking for trouble. Salem faces off with the leader whose beard and white turban say “tough yet reasonable,” while his band of several dozen men with rifles show that he is serious. They exchange words.

“God is always good to the devoted and the deserving. May he look at you and your people with favor and may he grant you long life. If a long life,” Salem says while pulling back his robe to reveal a handgun tucked into his belt, “is what you desire.”

The turbaned leader considers the gesture and cautiously answers. “If it is the will of God.”

“The will of God. Yes.”

“Khoda Hafez.”

“Khoda Hafez.”

And the real bandits charge off without incident in a swirl of orchestral strings. Colonel Salem and his men charge off into the mountains. The landscape is reminiscent of the American west and indeed Brynner plays it like a true cowboy, flexing his signature presence of resolute confidence mixed with gruff justice while demonstrating his knack for assuming ethnicities and condensing genres.

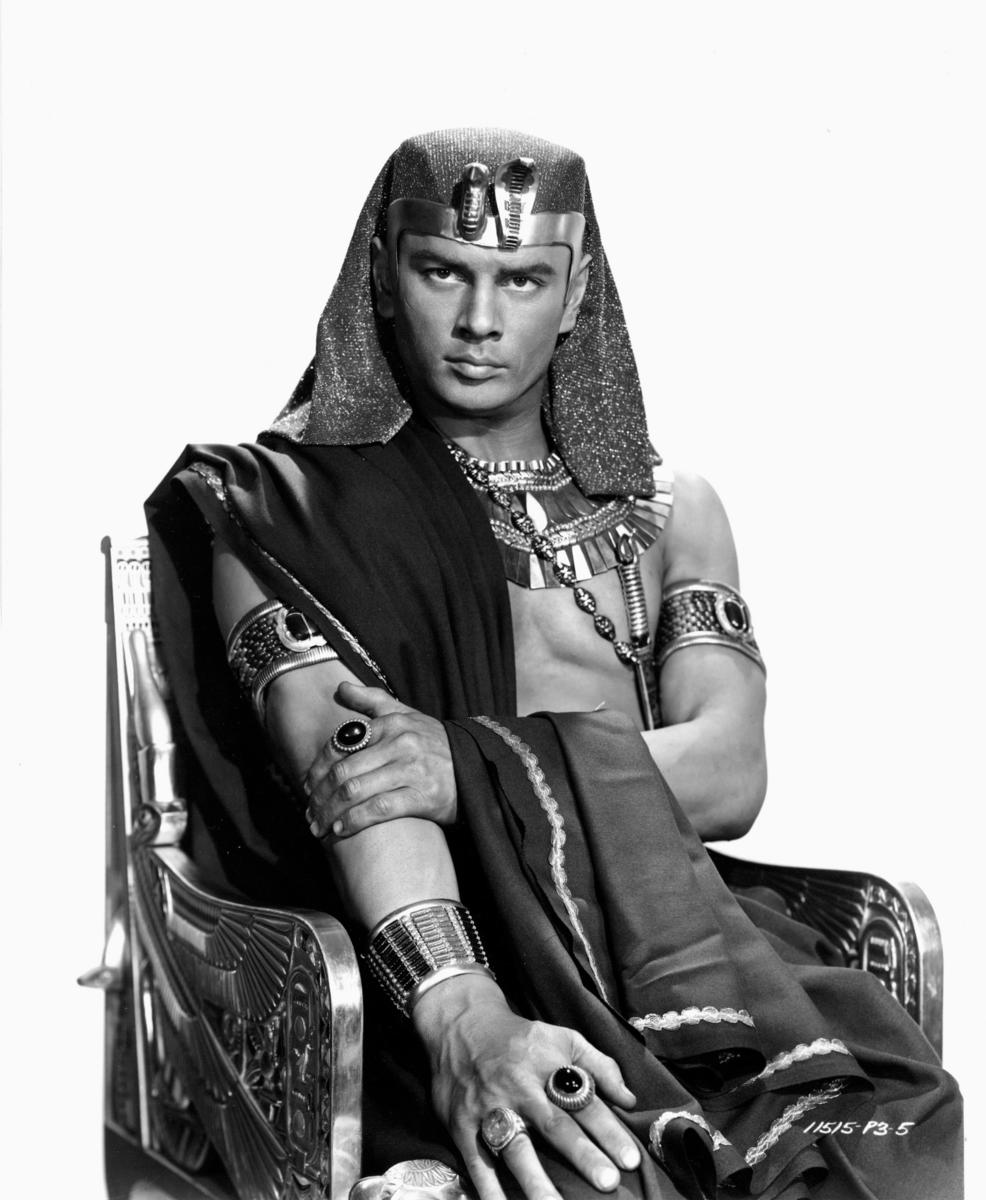

Brynner had broken out with his 1956 role as the King of Siam in The King and I, singing and dancing his way to an Oscar. He followed that up with another character who eschewed shirts, Ramses I, in The Ten Commandments. These characters basically cemented his career as the go-to guy for any role that required non-western features and vaguely accented, broken English. Brynner managed to bring a certain depth to these clunky stock characters. His trademark bald head offered a clean slate suited specifically for many roles, one that did not infer any one ethnicity. Even though it was clear that English was not his native language, he delivered his lines with precise enunciation. His accent was ambiguous and always almost identifiable, which somehow made it a plausible trait for all of the characters he played. He lent an air of sophistication to his characters, which enabled him to instill some sense of dignity in the face of choice dialogue such as:

“Look mother! The prime minister is naked!” (exclaims the teacher’s son in The King and I).

“Don’t be ridiculous!” she replies. “He’s only half naked.”

Brynner, of course, is not the only actor to portray individuals from other cultures. Hollywood always gave actors a chance to try on new accents, especially in the original golden age of epics and espionage, but only Brynner made an entire career out of it. He became American cinema’s Cold War–era ambassador from everywhere, slipping in and out of nationalities and representing the Hollywood worldview. What is particularly intriguing about Brynner, in addition to the diversity of the “exotic” identities he portrayed, is that his own biography is extremely enigmatic. On screen, he covered a staggering range of geographies and social classes, becoming everything from an Indian Sultan to a Mexican revolutionary to a Japanese fighter pilot (for a more complete list see the Yul Log,) while off screen he obscured his own identity by dodging questions or telling outright lies. Simple background facts like his birth date and given name are still difficult to pin down definitively (although his son Rock wrote a “tell all” biography called The Man That Would be King and spoiled all the fun). He often claimed to have been born as Taidje Khan in Japan to Swiss and Japanese parents, when in fact he was born in Vladivostok, Russia and is technically Swiss-Mongolian/Russian. After a brief stop in China, Brynner spent his formative years in Paris, joined the circus as a trapeze artist, played guitar in gypsy bands, hung out with Jean Cocteau, learned English on stage with Michael Chekhov, landed in New York, debuted on Broadway and became a big Hollywood star.

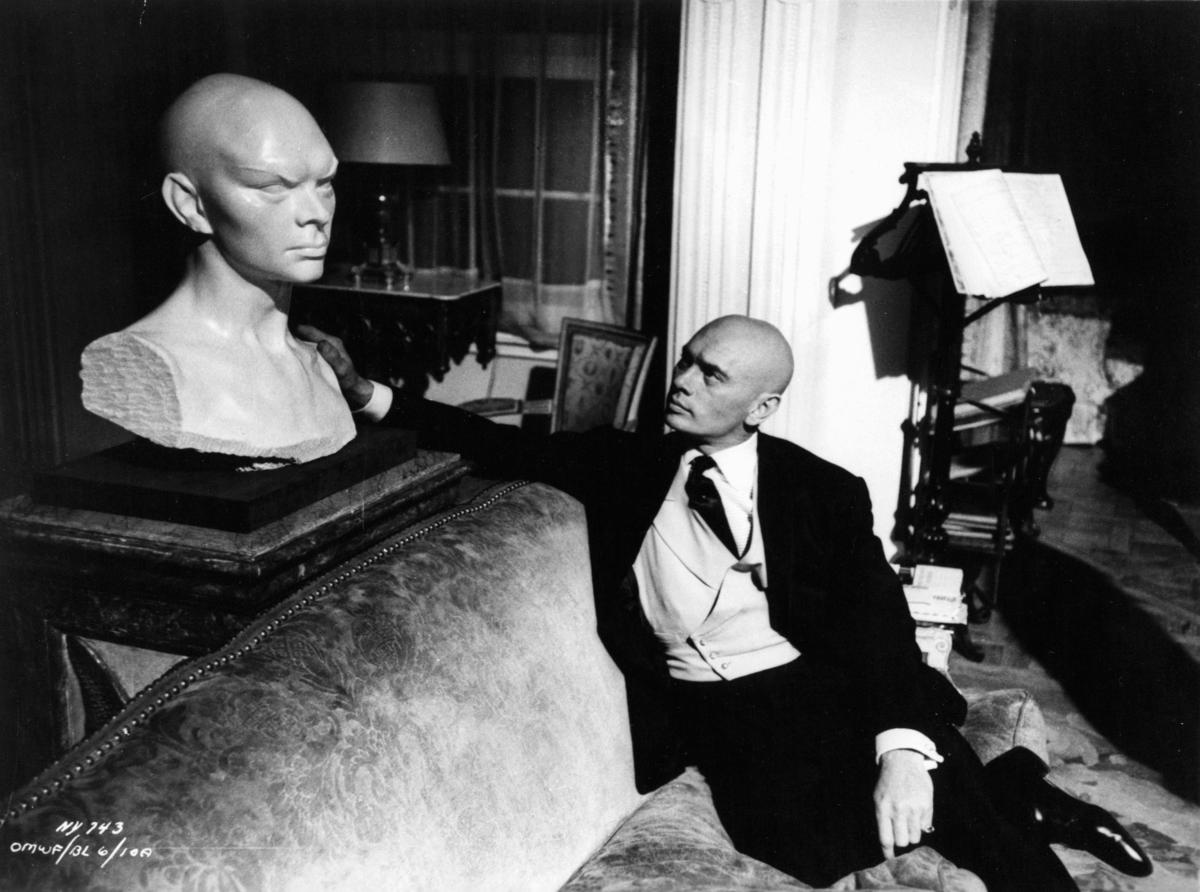

American audiences loved Brynner’s complexities: his Mongolian good looks and European finishing, his steely tough-guy stare and his dapper sensitive-guy dance moves, his affable confidence and guarded identity. They ate it up. After almost two decades of hits, B-movies, foreign action flicks, and a redefining role in The Magnificent Seven, Brynner came back in the sci-fi hit Westworld (1973), an early Michael Crichton film. Westworld is a wild west amusement park where a host of robots interact with guests, acting out scenes from brothels and saloons. In one of his best roles, Brynner channels all of his intensity into the part of a robot gunslinger who duels with guests but is programmed to always take the bullet. The audience of Westworld savors the irony of the recasting of his Magnificent Seven gunslinger as a theme park attraction. Of course, the robot malfunctions, stops playing nice, and a shooting spree ensues. Brynner’s chilling performance takes a lackluster Frankenstein premise and turns it into a very satisfying experience. The insipid sequel attempts to mine the other side of Brynner’s career. In his final acting role, he appears in Futureworld during a dream sequence that takes place in the mind of the leading lady. His gunslinger floats into the smoky scene and twirls her around and around in an elegant ballroom dance.

Ultimately, it was his excessive coolness that killed Brynner; in 1985, at the age of fifty-five (or perhaps fifty), he died of lung cancer after a lifetime of a five-pack-a-day smoking habit. It’s too bad, too, because if he had continued for another ten or fifteen years Brynner might have had the chance to cash in on Hollywood’s latest obsession with big budget spectacles, or perhaps he would have staged a comeback in the indie film world by giving us a smart and funny recasting of his genre characters tinged with irony and cultish in-jokes. Anything would have been better than the string of King and I revival tours that turned out to be his final performances.