By Etel Adnan

A little magazine is like the start of a river. Sometimes you see a river alongside a mountain and it looks like nothing — it’s only trickling. Think of Holderlin’s poem about the Rhine. What I like most about that poem is the beginning — he starts in a little crevice, like a little hole, at the beginning of the Rhine. And that’s what little magazines are. That they rarely last is almost part of their nature. They are not meant to last. They are meant to follow one person’s impulse, to gather bits and pieces, works by poets, writers, and artists, which may become literature much later. In this way, small magazines are full of hope. We don’t know how long they will live, and they often disappear; but better to disappear than to become a bad magazine.

I started out with magazines of this sort both in Beirut and in the US. I was first published in America in a little magazine from New York called The Smith. It later disappeared. When a little magazine comes in the mail, it’s like receiving news of a birth. There is something charming, unpretentious, adventurous about them. As they get bigger, they start to have editorial policies and complications and the more they look for famous names. Well, how can you become famous if you don’t start somewhere? A little magazine is like a little gallery in an obscure, forgotten corner. What a pleasure to know a little place where you might discover one or two or three new things. Twenty years later, you discover that this or that person has become known — and usually less good, by the way.

In Beirut, I remember Antoine Boulad, who had started a little magazine called Mauvais Sang. I gave him some of my poems.

In Beirut, too, there was Shi’ir. Youssef Al Khal, Shi’ir’s editor, changed Arabic literature forever. Shi’ir was the most important literary event of the 1950s and 60s. Thanks to Shi’ir I was encouraged to return to Lebanon. I remember walking in Beirut and encountering what was one of the first galleries in the city. It was called Gallery One and it was run by Youssef and his wife Helen. We talked about poetry, because he was really a poet. He said to me, You write poetry, why don’t you send me some poems? I saw him a second time and he said, What are you doing in America? There’s a movement here! He had such enthusiasm, so I eventually sent him some poems from California, where I was living at the time, and before long I began to see him regularly. He was like a best friend to me.

Eventually, they closed the gallery and rented a basement across the street from his home in the Zarif neighborhood. Simone and I used to go there and very often there were young Lebanese emigres passing by during the summer. We would drink whiskey and wine and at midnight Youssef would say, Let’s see the paintings! He would open up the gallery and everyone would leave with a tableau under their arm.

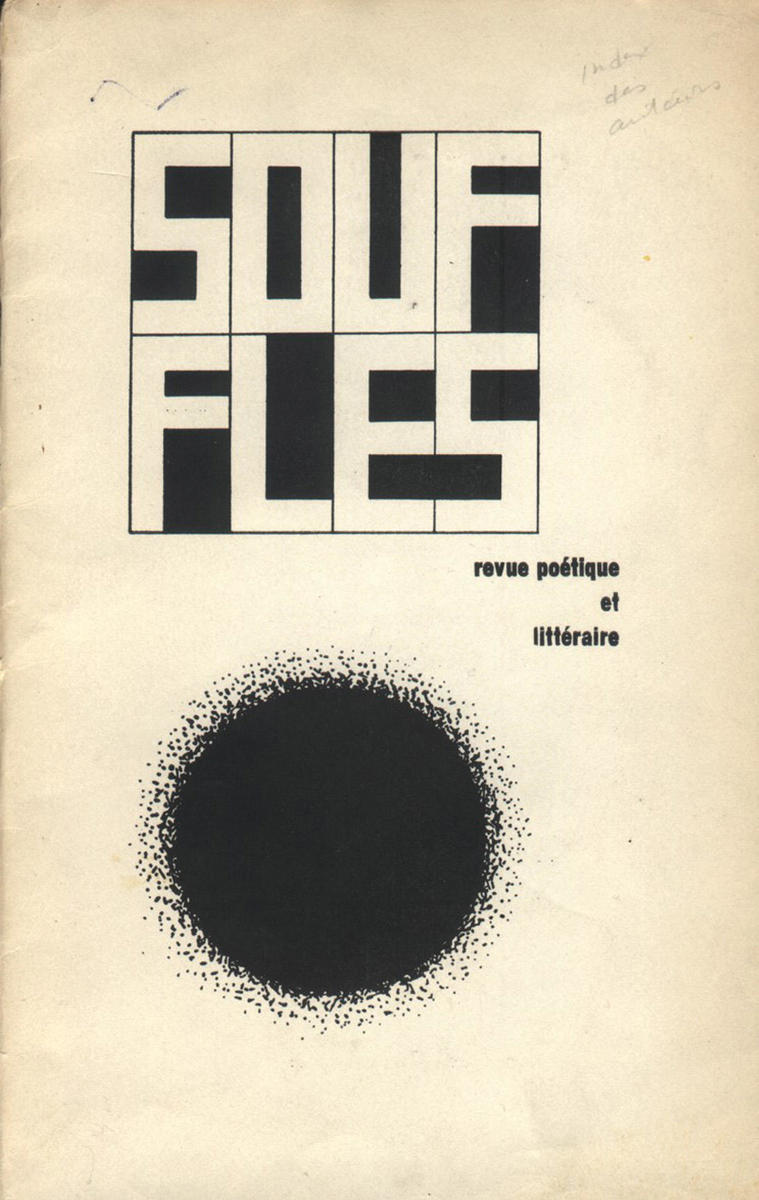

In Morocco, there was a little magazine called Souffles run by Abdellatif Laabi. In July of 1966, I went to North Africa for the first time. I was in Rabat and the night before I had found a magazine in the street under the arcades. It was the fashion in Arab cities to have books spread on the sidewalk and people sitting on the floor looking at them. I looked through this magazine and was reminded of a man who had been a teacher in Beirut — my teacher — a French writer called Gabriel Bounoure. He had left Beirut in 1953 for Cairo, and a few years later, for Rabat. I didn’t see his name anywhere, but I read a few lines and thought, These must be his students. He had been like a guru for poetry, not at all a classic academic person. He had a way to give to poetry its full importance. Like Heidegger did. When I found that issue of Souffles I recognized in the poems the rarefied air, the intensity, the rigor, and the heated quality of the poems that Bounoure would have taught in his classes. Of course, I knew he had been banished from Lebanon by the French government, as he had openly criticized French policies in Algeria during the war.

Inside the magazine there was an address. It was published out of a house. So I looked it up and knocked on Laabi’s door at 8pm and a French woman came out. It was his wife’s mother, who told me that Abdellatif was at the hospital because his first child was about to be born, but she was expecting him home soon. I waited, and at 9pm or later he arrived. I said I am sorry, I am leaving tomorrow and I saw Souffles and I was sure you were one of Gabriel Bounoure’s students. He said Yes, of course I am.

During those years, we still believed in Arab unity, and people like Laabi wanted a United States of Arabia. I said to him that we won’t wait for the government: we will make our own Arab unity. I told him I was going to Beirut soon and I would talk about Souffles there. Later, he invited the Syrian poet Adonis to contribute to his magazine. I suppose I was the first one to make the connection between those two literary universes. Later, I sent him my poem on Palestine, “Jebu” — not the whole poem, but large excerpts. We remained great friends.

Souffles had a fantastic influence. A first generation of French Moroccans had a place to publish. It was a political magazine, too, and they took many risks. One of my favorite North African poets, Mostafa Nissaboury, published in Souffles, as did Tahar Ben Jalloun.

Years later, when Abdellatif was in prison, I wrote to him a lot. I stayed in touch with his wife and I remember her telling me that she had taken him the complete works of Engels to read. I thought, These books were so hard to read, so I sent him some art books to bring color to his jail cell. He would always say that our friendship had the same age as his first daughter.

-September 22, 2015, Paris

Click here to read Issandr El Amrani’s piece about Souffles in Bidoun 13