I am hurt when I find a black American fighting the Muslims under the American flag.

— Ayman al-Zawahiri, deputy chief of al-Qaeda, May 5, 2007I am Suleyman Lindh. Eater of much wheat crop, drinker of much buffalo tea.

— John Walker Lindh, madrassa guestbook, Bannu, Pakistan, June 2001The Messenger of Allah, may peace be upon him, was asked: What deed could be an equivalent to Jihad in the way of Allah, the Almighty and Merciful? He answered: You do not have the strength to do that deed.

— Hadith, quoted by John Walker Lindh, e-mail from Yemen, February 24, 2000

It may be difficult to remember now, with the American occupation in Iraq crumbling and the Taliban creeping back into Afghanistan, that at one time the most vexing war-related question facing the United States was, “What the fuck is wrong with John Walker Lindh?” Lindh, you may recall, is the pale-faced California youth who converted to Islam and who, by dint of zeal, bad timing, and other misadventure, found himself pledged to the defense of Taliban Afghanistan on the eve of September 11, 2001. Routed by US airpower in the opening days of the American invasion that November, Lindh’s Taliban contingent marched over fifty miles to surrender to Northern Alliance forces, and the young American was imprisoned along with other “foreign fighters” in a dank fort basement near the town of Mazar-e-Sharif. Within days a POW uprising produced the first American casualty of the Afghan campaign — CIA asset Johnny Michael Spann, the only victim cited during Lindh’s trial for treason — not to mention over 300 functionally nameless Taliban dead. Lindh’s talismanic American-ness was found bleeding amid the rubble, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Lindh became an instant media sensation, and his capture spawned an electric, all-purpose, all-capped, mass-media meme: AMERICAN TALIBAN. The phrase, in all its novelty and oxymoronic giddiness, was a hit. The idea of a so-called American Taliban suggested a bracketing, self-sufficient alpha and omega in which “one of our own” could be both the Muslim maniac and his American victim. Lindh managed to appear as the most evil of turncoats and also the most clueless of post-hippie, Northern California rubes. (Ex-President George H W Bush dubbed Lindh a “misguided Marin County hot tubber,” even as George W. disappeared him into the new American terror gulag.) In classic ugly American fashion, the US had gone tripping off to an exotic locale, and once there, found itself with nothing to talk about except other Americans.

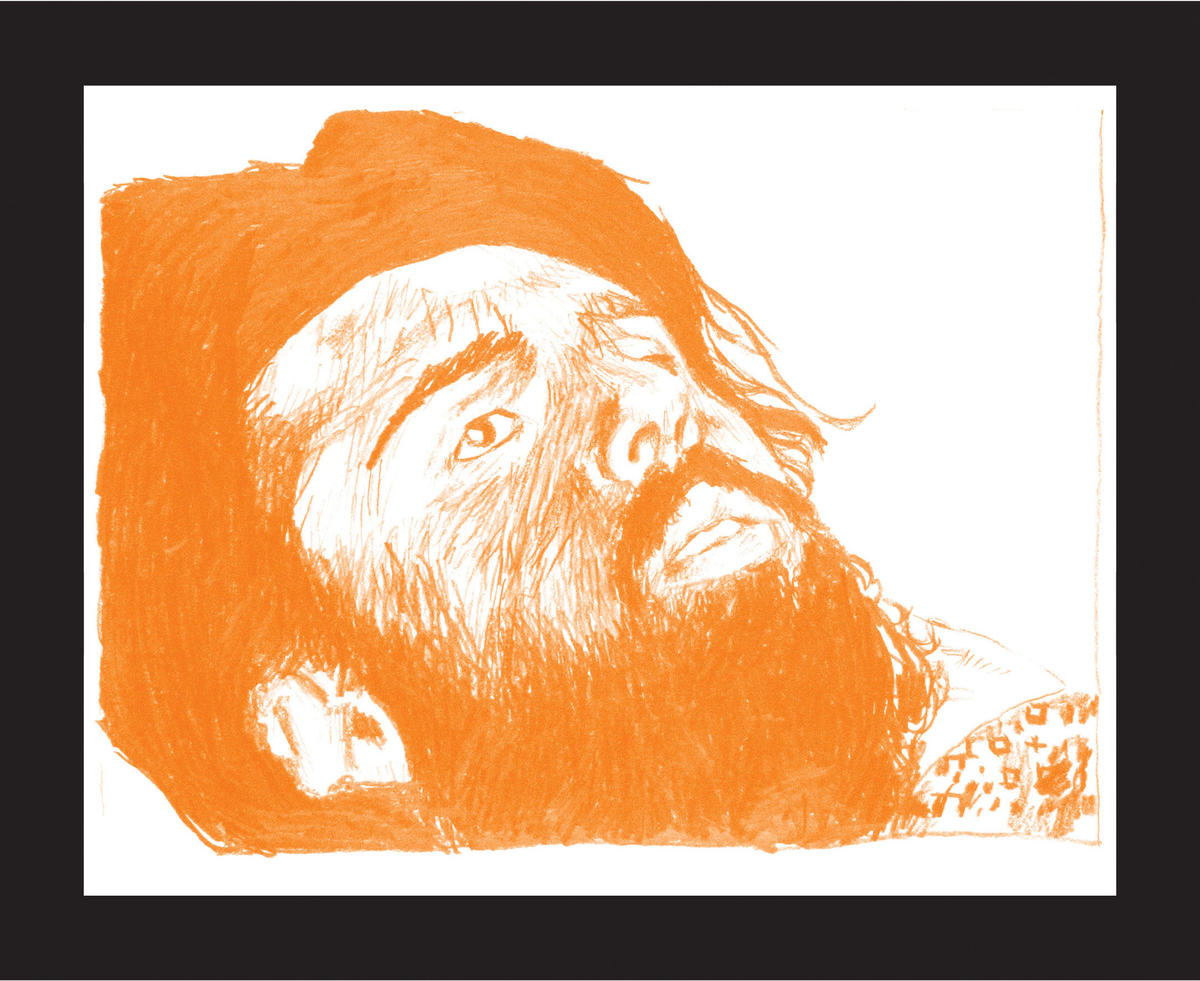

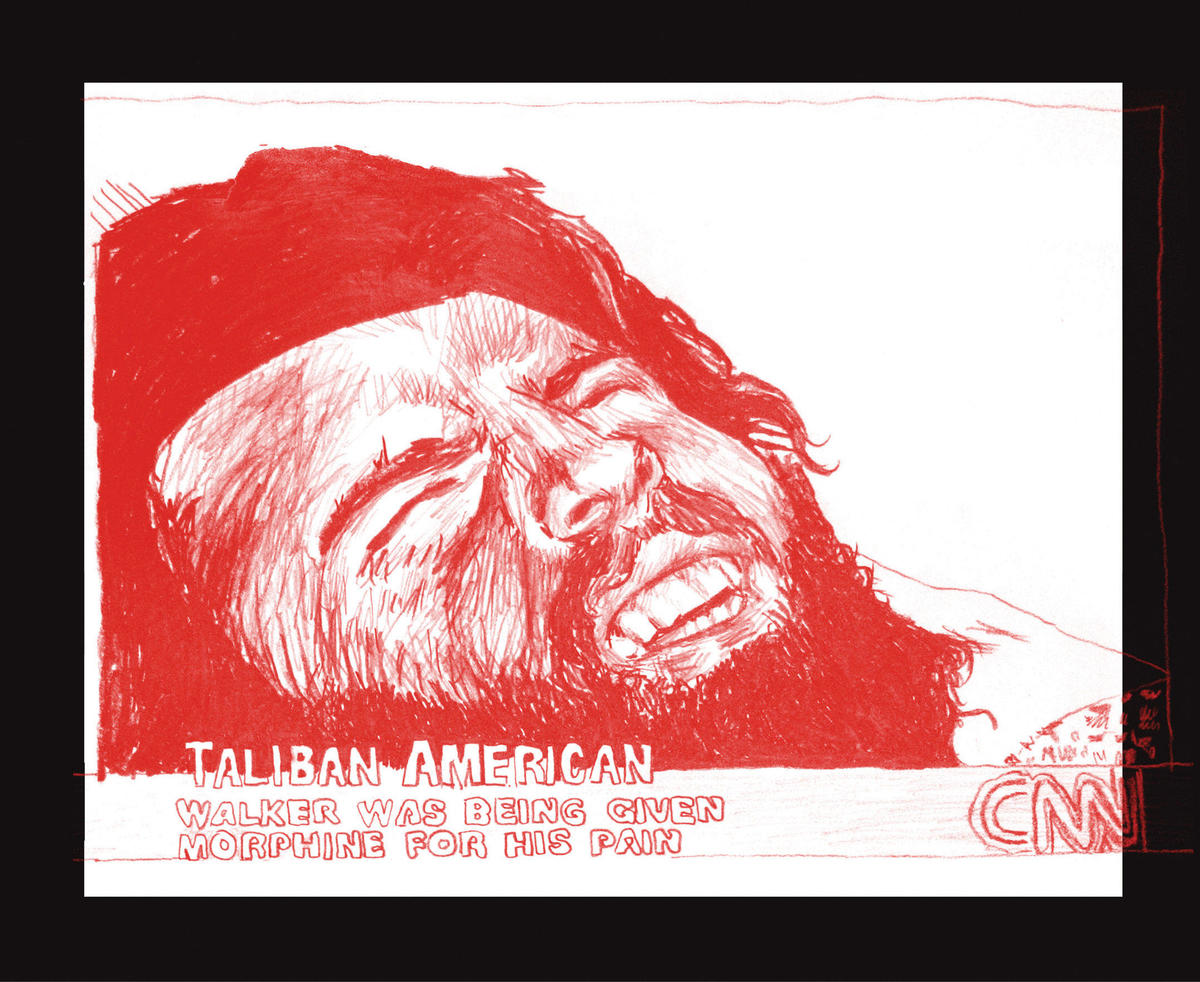

“John Walker Lindh: American Taliban” soon found a set of emblematic images in the form of: a collection of closely cropped vidcaps lifted from a CNN broadcast. Taken just after the dust settled at Mazar-e-Sharif, a recumbent, wounded, curiously interstitial Lindh is interviewed while his mind clearly wanders elsewhere. How did I get here?, he seems to be asking himself, a tragically lonely, vaguely symbiotic echo of the collective question being asked about Lindh by his countrymen. It is also the most torturously rhetorical thing he could possibly be thinking. The cast of Lindh’s features in these images suggests he knows exactly how he got there. How could he not? His own trajectory seems to be playing over and over in his mind’s eye in indelible and excruciating detail.

With these CNN images, Lindh became a bona fide object of American fantasy. He is fixed in our memories as a not unpretty young man, the kind of kid who might have a tough time in a civilian lockup in the States. His captivity and our attendant feeling that the boundaries of a private suffering have been transgressed combine with Lindh’s not unprettiness to lend the scene an overtone of emasculation. Smudged by successive cycles of cropping and enlargement, the images began to seem the product of painterly intention, a study in the psychology of violation. Lindh appeared to have been turned out, rendered thoroughly passive by war, the US Marines, Islamic fundamentalism, or some combination thereof. Or rather, as Lindh’s defense attorney argued in his closing statement, his client had been “overcome by history.”

There was a second group of emblematic “American Taliban” images, a set of military-produced photos documenting the security measures applied to Lindh during his transport back to the States. In these snapshots, the atrocities at Abu Ghraib in 2003 are literally prefigured. Lindh is bound, blindfolded, stacked like an object waiting for transport. The black metal walls in the background — Lindh spent two weeks bound to a stretcher locked in a shipping container — suggest the American Taliban has been extraordinarily rendered all the way to the Death Star, the precise locale of his torture unknowable.

But torture it clearly was. In one image, SHITHEAD has been scrawled on Lindh’s blindfold. In another his wounds are being meticulously photographed — whether for documentation or as trophies, it’s hard to say. Lindh was the first victim of the torture regime that would later take shape in Guantanamo and Iraq. Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld instructed his agents to “take the gloves off” when interrogating Lindh, and one can imagine the Bush Administration’s rage at an American traitor setting the tone for later assaults on more properly foreign enemies. At the time of his capture, Lindh already seemed to intuit that he would have a special role to play in the historic drama to come. “If you’re concerned about my welfare,” he told the CNN cameraman, “don’t film me.” This was not merely a demand that no images be made; it was also an almost legalistic affirmation that, being of sound mind if not body, Lindh understood the kinds of hell that would soon be raining down on an “American Taliban.”

In the interval between these two sets of images, that rain had arrived. The man in the transport shots could be asleep, drugged, or dead; but despite being tied and blindfolded he also seems engaged, expectant even. More torture is in the offing — he will be kicked and spat upon; he will accuse soldiers of trying to kill him during a deliberately clumsy attempt to remove a bullet from his leg — but for now Lindh just seems to be waiting. Of all the awful things he will soon experience, surprise is not among them, not because he believes that he deserves his fate but because the only thing that could possibly surprise John Walker Lindh would be fair treatment at the hands of the US government. He said as much to the CNN correspondent, explaining that the rebellion at Mazar-e-Sharif was broken when the surviving Taliban prisoners realized that, “I mean, if we surrender, the worst that can happen is that they’ll torture us or kill us, right?”

Lindh’s family has argued that young, starry-eyed John didn’t understand what the Taliban actually represented at the time of his enlistment in its irregular army. And yet, although consistently imagined by his family and lawyers as a naive Bay Area liberal, Lindh did not adopt any of the imaginary postures of that classical archetype when confronted with an impending American invasion. Lindh claimed no special American privilege, never sought to interpose himself between his countrymen and his fellows, never attempted to speak power’s language in hopes of cushioning the blow about to land on him or his compatriots, never appealed to America’s better nature. What would be the point? The Americans and their allies were acting exactly as Lindh expected them to act. “The worst that can happen is that they’ll torture us or kill us, right?” He was prescient, to be sure, but he was also experiencing a moment of wish fulfillment. Even the victims of Abu Ghraib have gone on record testifying to being surprised that America, of all countries, could have done such a thing to them, but the son of Marin County expressed no surprise.

Despite his disavowal of America, it is precisely this presumed intimacy with his country’s ways and wherefores that lent the scene of his torture its particular and disturbing ambivalence. For Lindh’s images were always immediately understood to depict an American. Our aghast consideration of his nakedness, frailty, and abjection was easily distracted by the chiaroscuro afforded by the paleness of his skin and the dark, Mansonian luxury of his hair and beard. (Did any prisoner in Abu Ghraib have locks so extravagant, so Californian? If they did, the images of their suffering have yet to surface.) There was an erotic subtext to the images that was entirely absent from the more famous snaps of torture at Abu Ghraib, even accounting for the nudity, simulated sex acts, enforced bondage poses, and homosexual taunting. What happened at Abu Ghraib was in essence political and racial, not sexual. Sadistic, yes — but it was flatly impossible to imagine any form of desire, expectation, or wish fulfillment at play in the experience of any of its victims. Whereas Lindh’s very American-ness, even in its denial — especially in its denial — made possible a more properly Sadean engagement between victim and victimizer. Conservative US talk show host Rush Limbaugh’s comment that the incidents at Abu Ghraib were analogous to “fraternity hazing” found its only plausible referent in the torture of Lindh. In the logic of the American fraternity you are desperate for the man behind you to abuse you: his violence is not just what makes him who he is, it is also what makes you his brother.

By the time the CNN and transport images were out of heavy rotation on American screens and newspapers, the main front in the war to imagine John Walker Lindh had moved back to California. Not six months of invisible captivity had passed before newspapers in his native Bay Area had peeled away enough layers from his strenuously progressive childhood to reveal the inevitable strata of American tabloid scandal: Lindh’s father, his chief spokesman and defender, had apparently left his mother for a man when Lindh was a teenager. The factoid allowed commentators already tut-tutting over his home-schooled hippie upbringing to murmur that the son’s fundamentalist turn might be understood as a form of adolescent rebellion.

Time magazine would mine the same territory to diametrically opposed effect. Mangling the Borat-like statements of a Pakistani acquaintance — “He was liking me very much. All the time he wants to be with me. I was loving him” — the magazine intimated that although Lindh had gone overseas for language instruction, he had also gone in search of carnality (of a sort that had somehow eluded him growing up just outside of San Francisco with a supportive gay father). The gay-Pakistan-idyll storyline was later debunked, but even in disrepute the idea that something was rotten in the Denmark of Lindh’s manhood took hold in the popular imagination, aided and abetted by the limited visual record and as impervious to contrary fact as the belief that Saddam Hussein had colluded with al-Qaeda to take down the World Trade Center.

Attempts to queer Lindh were so successful because the rumors indicated something true about him. But it wasn’t Lindh’s heterosexuality that was unstable; it was his whiteness. Long before he was the American Taliban, Lindh had been a member in good standing of a chimerical pop-cult tribe that has, in various permutations, served as an ubiquitous feature of the American imagination for over half a century; that by now pedestrian oxymoron, the White Negro.

First identified by Norman Mailer in his 1957 essay “The White Negro: Superficial Reflections on the Hipster,” the White Negro is defined by his (almost always it is a he) subversive, countercultural intent and by his deep identification with black people or, at least, black music. For the original generation, it was jazz: Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, and bebop as a style. In the late 1960s, free jazz sounded the (blaring, police) siren song that seduced the White Panthers and other revolutionaries. But by the 1980s, the predominating black musical idiom was rap, and in the age of hip hop, the White Negro was often called, mostly disparagingly, the wigger.

Lindh was a white fan of hip hop, a dedicated listener who fantasized about becoming an MC himself and whose identification with “the culture” bordered on the obsessive. As it happens, Lindh’s desire to transcend (or at least, transgress) his racial origins is not completely distinct from the story of his conversion to Islam. Indeed, wheels-within-wheels, it was a transformative encounter with one of the great black narratives that set him on the road to Afghanistan. Lindh saw Spike Lee’s X at the age of twelve. Nearly every witness, feature writer, commentator, and lawyer describes young John as having experienced a kind of roadside conversion in the darkened theater, his boyish mind especially blown by the scene his mother describes as “showing people of all nations bowing down to God.” This was the climactic re-staging of Malcolm X’s first hajj, when the icon of African American self-determination and American self-creation is introduced to a “real” multiracial Islam, quite unlike the thoroughly syncretic, black-only religion he had practiced as a member of the Nation of Islam. (It was after this hajj that Malcolm took his “proper” Islamic name — Al-Hajj Malik al-Shabaaz — and soon after that he was dead. For Lindh, a lifelong fascination with Malcolm began that day. The film’s assertion that Islam allowed Malcolm X to transcendently reconsider (re-reconsider, really) the nature of being a black American clearly spoke to a deep and tumultuous need in Lindh’s own life.

As James Best, writer for the East Bay Express, reported, “[Lindh’s] admiration for Malcolm was channeled into an exploration of the black nationalism and quasi-Islam that saturated much of the hip-hop of the late 80s and early 90s. His posts on the online message boards of the Usenet — particularly the newsgroups rec.music.hip-hop and alt.religion.Islam — are a strange and public window into a young man’s discontent… [T]he Web gave him the space to visibly and coherently remake himself as ‘an intelligent MC smashing empty-minded pimps.’” Most of his posts are still readily searchable using Lindh’s decidedly un-Islamic e-mail address as a parameter: doodoo@hooked.net. They reveal a tellingly banal cross section of earnest, brainy adolescence, from boastful, typo-filled posturing —

I don’t read this newsgroup often, because collectively it’s users are little more than worthless dickriders and overly competitive pretend MC’s trying to prove themselves to the rest of us. However, when I come here I do enjoy your many posts, and the hilarious lyrics. It’s impossible to tell whether your comedy is intentional or sarcastic, but it’s undoubtedly brilliant.

— to touching angst about the permissibility of his various interests:

I’ve heard recently that certain musical instruments are forbidden by Islam. There is nothing in the Qur'an that I can find relating to this matter, and the Hadith that I’ve read were fairly vague. My question is this: are in fact certain musical instruments haram, and if so, which instruments or types of instruments are they? Thanks in advance to anyone who can help.

Most curious were the e-mails wherein Lindh pretended to be black, hectoring his presumptively black correspondents for what he asserted was their betrayal of a deeper, truer hip-hop aesthetic. In many of the postings, Lindh enacted the specter of his own racial unmasking, accusing his correspondents of “acting black” even as he reserved for himself a higher form of black consciousness.

When I read those rhymes of yours I got the idea you were some 13 year old white kid playing smart. That “Every Black Man Should Read This Rhyme” read like a child’s poetic attempt and deepness, and was further hindered by lines like “Why do these collad greens taste so good?” It was clearly implied that the answer to each of your questions was “because you’re black,” but how does African heritage and a good hearty dose of melanin make greens taste good?

That whole rhyme was saying essentially that all black people should just stop being black and that’d solve all our problems. Our blackness does not make white people hate us, it is THEIR racism that causes the hate. That collad green line alone leads me to believe you’re one of those white kids who thinks that if he eats enough collad greens, watermellon, and fried chicken, and sags his pants low enough, he’ll attain the right to call himself “nigga.”

Lindh’s tone was most often that of what hip-hop aficionados call a backpacker, a hip hop fan of any race who has decided to renounce the genre’s late turn toward bling, bullets, and bitches in favor of a conceptually and aesthetically pure old-school or “true-school” practice. Unlike rappers whose fame depends on ill-gotten wealth, a propensity to violence, physical charisma, and/or hypermasculinity, the backpacker — think Talib Kweli — is ascetic, diligently focused on rigorous rhyme schemes, oppositional politics, black uplift, and a monkish devotion to one or another body of arcana. This tendency to textual geekery can as easily find an outlet in Marvel comics as in the Qur’an; very commonly it involves both. Hence the backpacker’s fascination with the Five Percent Nation, an African American sect that split off from the Nation of Islam in 1964 and whose gods and earths, supreme mathematics, and cryptographical enthusiasms (ALLAH: Arm Leg Leg Arm Head) put the sect well beyond the pale of nearly all Muslim practice and theology.

For a while, all these true-school tendencies were legible in Lindh, his performance a high-wire tightrope walk of identification where aspiration and disavowal constantly threatened to throw the would-be racial daredevil off balance. Lindh’s e-mail expressed a communion with a pure, iconic blackness, even as he vehemently attacked what he viewed as a fallen and polluted black cultural mainstream, a cesspool of market-driven hip hop and bourgeois assimilation. Lindh played a fanciful game of Blacker Than Thou, his rectitude and faithfulness having allowed him to discern something fundamental in hip hop that the vast majority of black fans and artists had either missed or lacked the strength to properly contend with.

The problem, Lindh finally concluded, was with the Negro. In this conclusion, he has not been alone. Blackness is a god that fails as often as it delivers. For blacks, there are time-honored, ritualized ways to respond when iconic darkness fails: you can become a black conservative; embrace black separatism; devote yourself to integration or assimilation; or disappear into the American mosaic, the pools of miscegenation and hybridity. If you’re white, though, and the Negro disappoints you, if the revolution in consciousness that you depended on the Negro to spark fails to ignite, your options are significantly more constrained. You can return to a stable form of whiteness that predates your own untrustworthy racial identity (ie, white supremacy) or you can keep on moving, in search of a new covenant with someone purer still.

John Walker Lindh seems to have decided in 1997 to keep moving. That year, at the age of sixteen, he officially converted, pledging himself to an Arabic, as opposed to Afro-Atlantic, Islam. In one of his last posts to the newsgroups, he launched an attack on Nas, a rapper with well-known links to the Five Percent Nation:

Is Nas indeed a “god”? If this is so, then why is he susceptable to sin and wrongdoing? Why does he smoke blunts, drink moet, fornicate, and make dukey music? Why is it if he is a “god” that one day he will die? That’s a rather pathetic “god” if you ask me. …Perhaps one day the members of the 5% will wake up and see who is in fact the slave and who is indeed The Master.

Gone is the pretense of one African American trying to save or teach another. Lindh’s smug, self-satisfied sneer now bespeaks fundamental elevation, a moral vantage point from which the benighted African American, perennially mired in his classic vices of drinkin’, druggin’, fuckin’, and dancin’, can be perceived in all his debauched entirety. It is as if Lindh, having misunderstood the lesson of Malcolm X’s hajj, finds in himself the strength (or, more accurately, the freedom) to do something Malcolm quite literally died rather than do: abandon the misbegotten American Negro to his lot.

This radical disappointment with the African American’s refusal to play his appointed role in white fantasies of absolution and purity has a long history. Michael Taussig writes in Mimesis and Alterity: A Peculiar History of the Senses about the late nineteenth century fascination with phantasmagoric “white Indians.” Even as African Americans agitated for equal rights (or, at least, freedom from fear of lynching), individuals and institutions became obsessed with reports of blond, blue-eyed Indians roaming the interior of Central America. Having effectively done away with the North American native, and having remade the African as the troublingly in-between African American, the white unconscious seized upon the White Indian as its last best chance at a meaningful encounter with nothing less than authenticity itself.

The White Indian was, of course, not just non-African, but also non-Oriental and non-Hindoo — a creature imagined as unspoiled, nomadic, and antagonistic to every aspect of the modern. Their (largely imaginary) blondness was as shocking to the nineteenth century as blond, blue-eyed Muslims were to Malcolm X on the hajj. And what better way to describe how “traditional” Arab Muslims must have appeared to John Walker Lindh than as “White Indians?” For an isolated California teen whose entire connection to the Arab world was a Spike Lee movie and the internet, an ex-White Negro disappointed by his chosen race’s fall into sloth, faithlessness, and (ultimate irony) irreducible American-ness, Islamic fundamentalism must have been a bracing, nearly inevitable tonic. The African in America will always disappoint the white American; it is why he exists. But the righteous, energized, clean-living foreigner? That is another matter altogether.

Lindh threw himself into his new religion with impressive vigor. He visited a nearby mosque in Redwood, only to decide that the place was too lax to meet his needs. He preferred the Mill Valley Islamic Center, nine miles away from the his parents’ house, which required Lindh to take the bus or ride his bicycle. Within weeks of converting, he was wearing flowing white robes and a small round hat, a sartorial choice that earned him stares and worse from the general public but also the grudging respect of his new coreligionists, many of whom favored Western clothing. His best friend at the mosque made a point of introducing Lindh to other Muslims, hoping that the convert’s zeal might prove infectious.

When he began researching foreign places to go to study Arabic, Lindh gravitated to Yemen, where the spoken language was purported to be more lyrical, closer to the Arabic of the Qur’an, than the lesser dialects spoken across the Gulf. Upon arriving at language school in Sana’a, Yemen, a disappointed Lindh berated his hosts for their integrated (that is, male and female) classes and tried (unsuccessfully) to wake them at dawn each morning to answer the first call to prayer.

He was, in other words, a true-school backpacker for Allah, dismayed to discover that being in a Muslim country, even a conservative Muslim country, was no guarantee that real, flesh-and-blood, born-not-made Muslims would match his devotion. Restless, he moved on to Pakistan, where he traveled the storied Northwest Frontier in search of an amenable madrassa. He found one at Bannu, near the Afghan border, with a headmaster who spoke passable English. Lindh spent nine months there, devoting himself to the project of memorizing the Qur’an. By now reasonably fluent in Arabic, Lindh — or Suleyman, as he called himself — learned about the great battles taking place in Palestine, Kashmir, and Afghanistan.

The Afghan story seems to have struck a particularly resonant chord. Afghanistan under the Taliban seemed to represent the oldest-school interpretation of Islam in the world, a place where the orthodox Muslim true-school had taken power and instituted the most ascetic form of Islamic governance imaginable. It was a vision that inspired his teacher at the madrasa, and it spoke to every fantasy of exactitude and rigor the young Lindh had ever had. At about this time, Lindh read Join the Caravan, a book by Shaykh Abduallah Azzam, a Jordanian-born fighter and theorist whose central theme was the importance of jihad — not merely in the sense of “striving to overcome one’s personal faults,” which Lindh had described in his statement to the court, after his trial — but in the taking up of arms to defend Muslims wherever they are under attack. Azzam had died fighting the Soviets in Afghanistan, and many believed that the Taliban’s struggle against the Northern Alliance was a continuation of that fight. For Azzam, jihad was as fundamental to Muslim practice as fasting for Ramadan or praying five times a day or making the hajj. It was the ultimate test of faith; if necessary, it would entail making the ultimate sacrifice. (Azzam famously called the jihadist movement a “caravan of martyrs.”) One day in May 2001, Lindh decided he was ready. He left the madrasa, received several weeks of military training, and finally arrived in Kabul. Six months later, he would have his encounter with history.

Since its diagnosis in Mailer and other mostly white male Jewish writers of the Beat Generation, the White Negro has been obsessively concerned with the question of his own manhood. For Mailer’s generation, the dangerous game of transracial identification required one to keep cool at any cost, for fear of appearing “impotent in the world of action and so closer to the demeaning flip of becoming a queer.” Eager to cast off the slur of Jewish weakness by valorizing a connection to a rough-and-ready black masculinity, these writers echoed the German Zionist’s striving for clear heads, solid stomachs, and hard muscles, with blackness standing in for physical labor and outdoorsmanship. In the iconography of the White Negro, these white men had tested themselves through immersion in one or another black-male-identified context: the playing field, the bandstand, the street corner, or (most iconically) the criminal underworld and the prison house. Those who passed their test were afforded the presumption of manliness, the removal of a stain as foundational to their identity as the presumption of their racism.

In order for such tests to have any power or meaning, there has to be an element of risk. No catharsis is possible without the possibility of failure, and for the White Negro the arbiters of this failure — the judge, jury, and, if necessary, exacter of punishment — are black men. Against the backdrop of this fantasy of black hypermasculinity, anyone who fails the test of manliness is revealed to be the black man’s opposite, which, in the way of such things, is not the white or the female but the homosexual. And the ultimate penalty for failure — for doing the crime without doing the time — is rape.

This penalty of rape for manly failure is so fixed and overdetermined that it is not merely white men who have to fear it. For black men like Malcolm — that is, for the vast majority of black men who convert in jail — Islam (syncretic or otherwise) brings with it a restoration of dignity, the recovery of a lost or debased manhood. This is a reflection of Islam’s emphasis on moral rectitude, to be sure. But it is also a function of the pragmatic benefit that comes with group membership inside the American prison system. The brotherhood of black Muslims serves as a bulwark against both predatory sexual assault and the ever-present lure of male intimacy during decades of incarceration. For the convert, Islam is the guarantee that he has neither violated nor been violated — or if he has, that that failure has been washed away, along with all the others, in the course of his remaking.

Is it any wonder, then, that the photographs of John Walker Lindh at the end of his long journey from Marin Country to Mazar-e-Sharif have the air of the prison house rape to them? His expression suggests a soft American boy who has decided to ride the wrong whirlwind. He is depicted as utterly alone, with no Taliban and no Malcolm to protect him, his only brothers the American soldiers who will surely abuse him. After Lindh returned to the States, after he had been tried and sentenced to twenty years — stiffer punishment than any other American citizen accused of post-9/11 crimes — the American narrative about the American Taliban would focus exclusively on the persistence of his faith in prison despite near-constant harassment. But on that late November day in Afghanistan, Lindh appeared as a man who had failed some or another well-imagined test. Whether betrayed by non-martyrdom on the battlefield or the softness of his convictions or by the memory of his violation by men or armies or history, he now seemed to be asking himself whether he had engineered this test in order to fail it. This was, after all, a man who’d styled himself a black man once, and if the logic of “asking to be raped” has any currency, it will be found in the scorn heaped upon men who assert for themselves reserves of masculinity they turn out not to possess. There are hundreds of rap lyrics that talk about this exact dynamic, including some of the oldest rhymes in the genre, like in “The Message” (1982) by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five:

You’ll admire all the number book takers

Thugs, pimps, pushers and

the big money makers

Driving big cars,

spending twenties and tens

And you wanna grow up to be

just like them, huh,

Smugglers, scrambles, burglars, gamblers

Pickpockets, peddlers even panhandlers

You say: “I’m cool, I’m no fool!”

But then you wind up

dropping out of high school

Now you’re unemployed, all non-void

Walking ‘round like you’re

Pretty Boy Floyd

Turned stickup kid,

look what you’ve done did

Got sent up for a eight year bid

Now your manhood is took

and you’re a may tag

Spend the next two years

as a undercover fag

Being used and abused to serve like hell

John Walker Lindh must have heard those lyrics dozens of times during his backpacker years. He may even have quoted them approvingly in his struggle to save hip hop from itself, before he he set out for the lands of Islam. Did he remember them that day in Mazar-e-Sharif? Did he think about his father?