Hamburg

Akram Zaatari: Objects of Study

Sfeir-Semler Gallery

January 26–March 17, 2007

There’s something peculiar about the faces of people posing for pictures in a photographer’s studio. Whether smiling or thoughtful, serious or sad, in their expressions the public and the private collide. Standing still before the camera, studio clients are afforded the luxury of pursuing their greatest fantasies (film star; sheikh) — all within the confines of the studio, complete with its own particular codes, customs, and theatrics. You could say that what emerges on the photographic print is a curious amalgam of all of these factors.

It is the complexity of the studio image that Akram Zaatari seeks to investigate in his ongoing Madani Project. For some years already, Zaatari has been working on compiling, structuring, and (re)contextualizing photographic material gathered from the former Studio Shehrazade in Saida, Lebanon, where he was born in 1966. Recently, the prolific Beirut based video artist, photographer, curator, and cofounder of the Arab Image Foundation introduced parts of the project under the title Objects of Study, in the Hamburg gallery spaces of Andrée Sfeir-Semler.

Established in the early 1950s by photographer Hashem el Madani, Studio Shehrazade accumulated a rich store of photographic images over the decades, documenting everyday life in Lebanon — banal and momentous — against the backdrop of the country’s tumultuous war marked history. The complete archive of Studio Shehrazade has been incorporated into the Arab Image Foundation in Beirut — itself an archive devoted to preserving the photographic legacy of the Middle East and its diaspora.

From the photographs taken at Studio Shehrazade, Zaatari grouped images according to various topics or motifs and supplemented them with commentary by the photographer. In Hamburg, viewers encountered five series of black and white prints produced between the 1950s and early 1970s. In one series, based on negatives from 1966, young boys in Madani’s studio enthusiastically embrace a cardboard cutout of a sexy blonde, a Gevaert film advertisement. In another series, eight young men are portrayed frontally and in profile: images used in applications for military training in the early 70s.

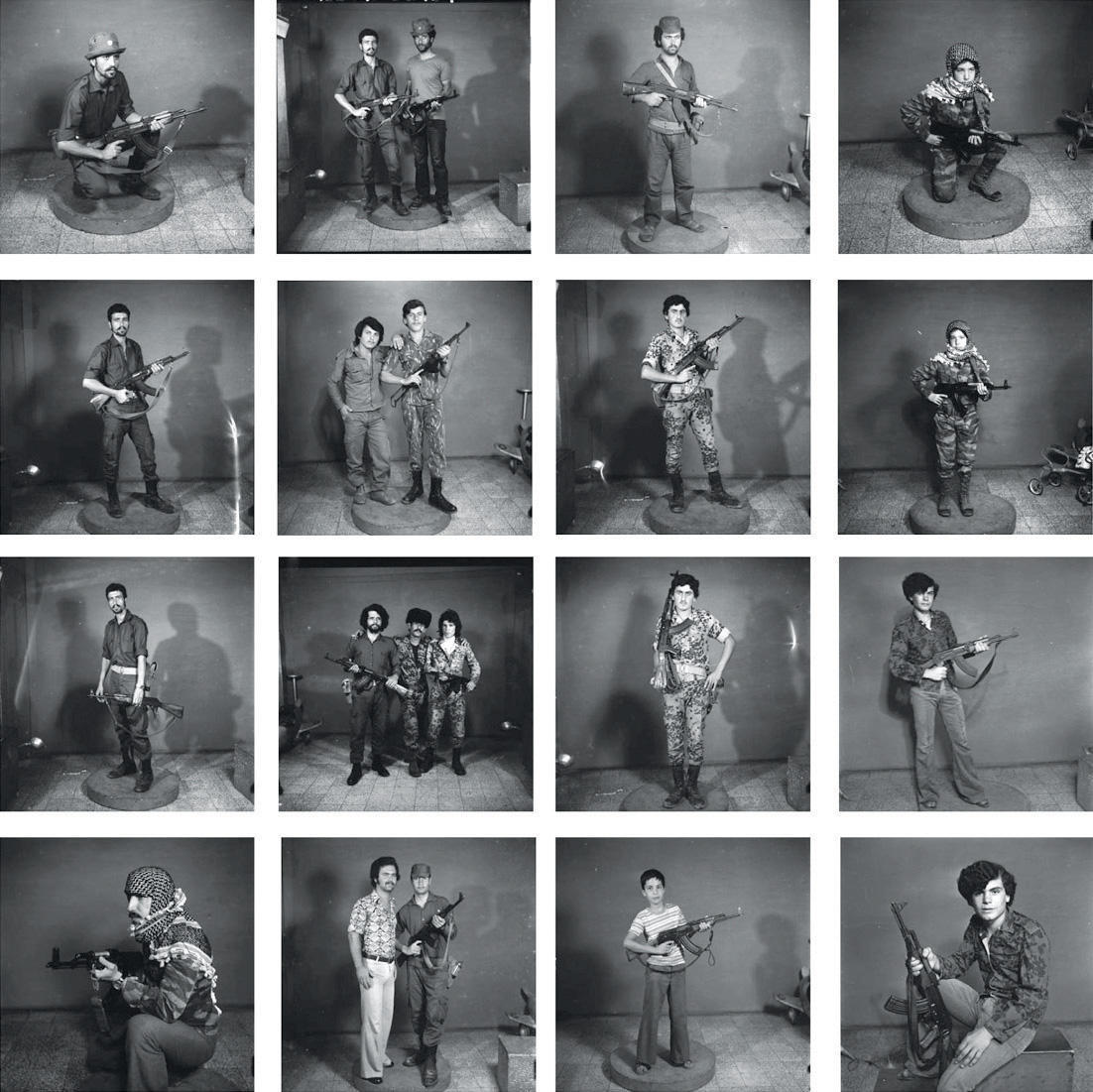

These pictures, in which the individual was transformed into a type, resonated with another series depicting fourteen young men in camouflage under the caption “After they joined the Military Struggle.” Capturing the young men in the stance of heroes proudly brandishing guns, the images conveyed an interesting ambiguity. Posing on the studio pedestal, behind which a toy plane partially revealed itself, the ostentatiously armed subjects of the photographs oscillated between freedom fighter romanticism and the harsh, even ugly, reality of militarism. That ambiguity was further emphasized by their oddly clichéd poses, reminiscent of cinematic renditions of military heroics and revealing a playfulness undermined by the fact that the guns held with such visible fervor were, in fact, the real thing.

One of the other two series presented in the central space of the gallery showed people walking or cycling in varying constellations towards the photographic eye — and thus toward the viewer — on a bridge in Saida. In the other, hung a contact print sequence, the studio photographer’s futile attempts to achieve pictorial results with a defective flash, while on the wall opposite, a triptych drew viewers’ attention to mysterious images isolated from the same series, in which the camera had been directed towards the floor. All of the images were installed in the gallery in the precisely elegant mode of a scientific research series.

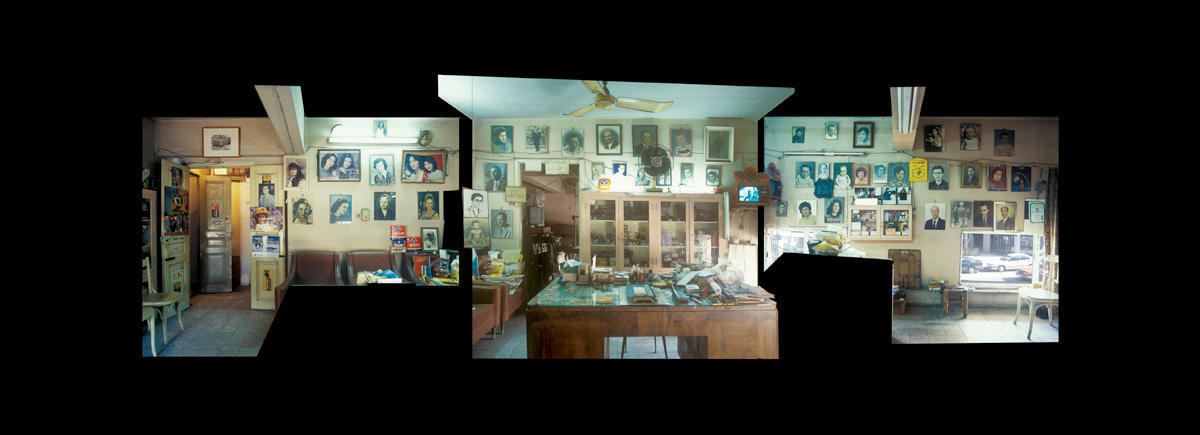

Indeed, it was Zaatari’s declared objective to focus exclusively on documentary material. “I am not interested in fiction,” he claimed. “I am attached to field work.” Still, through the placement of the documentary images within the gallery, a new set of associations was triggered, filtered by the viewer as well as by Zaatari. Upstairs, the various visual threads introduced in the first section of the exhibition were pulled together in a panoramic view of the intriguing reception space of Studio Shehrazade, represented in color, as well as pictures of the items located on the desk of the studio photographer. Zaatari displayed the different time-worn instruments Madani used in his photographic work in generically ordered arrangements, much like specimens found at an archaeological site.

Finally, in Video in Five Movements (2006), a collage based on Super 8 home movie footage filmed by Madani in the 1960s and 70s, Zaatari explored how “a still photographer conceived movement and spontaneously directed his friends and family members, including himself.” The video gradually flowed from singular representations of the studio photographer to the depiction of a larger group of people. Stillness and motion: between those poles, Zaatari’s subtly exciting “excavations” of Studio Shehrazade crystallized moments of contemporary Lebanese history, revealing not only the specific studio practices of Hashem el Madani, but also throwing light on how studio photography can animate an epoch.

By employing quasi-scientific methods and giving the photographic material he works with a new shape through the specific choice and juxtaposition of images, as well as by means of their placement in the sphere of art, Zaatari points to the tension between the “objective” and the “subjective.” Viewers, encouraged to read the images and thus to participate actively in investing them with meaning, become entwined in the dialectical interrelationship that obscures the boundary between the observer and the subject of observation.

In this sense, Zaatari is not only an excavator but also a creator of images, revealing the manifold hidden layers inherent in studio photography as a tool of recording, but also as a way of staging, mirroring, and distorting reality. In the Hamburg show, Zaatari’s carefully chosen images, adopted from the studio archive, had significance far beyond the mere documentation of lives in a certain time and place: the personal stories and histories underlying the photographs comprised, in a way, the story of ourselves.