“I cannot make out a difference between presentation and representation,” says Natascha Sadr-Haghighian, stubbing out her Marlboro Medium in a porcelain ashtray. “Everything you present already represents something at the same time.” If such assertions have become rather commonplace in the contemporary art scene, Sadr-Haghighian is one of the few who have taken them to their logical conclusion in one of the most tenacious highgrounds of authenticity, the artist’s biography.

How to write a profile on an artist whose current intellectual concern is to subvert identity precisely in the “curriculum vitae,” “career profile” sense of the term? Sadr-Haghighian’s project “bioswop.net,” one of many collaborations with the Berlin-based possesst group, is a website offering the possibility to trade in your CV for someone else’s on the “CV market,” or to use a “CV DIY kit.” The idea of the “death” of the creator, most famously defined by Michel Foucault and Roland Barthes, aimed at diverting attention away from the author/artist, towards the reader, and the ideological context in which both writer and reader do their writing and reading. Though such notions have been successfully integrated within literary studies, in the visual arts, the artist’s persona, and, by proxy, her intention, are still routinely upheld as hermeneutic guidelines. If the role of a biography is already a tricky issue when it comes to discussions of homegrown artists in homegrown contexts, it turns rather burlesque, arbitrary and embarrassing when it comes to artists from geographically removed — or indistinct — places. Sadr-Haghighian has now started using biographic data according to shifting criteria. For example, on the website of the Johann König gallery representing her, Sadr-Haghighian’s bio specifies professional activities that have little to do with her artwork (but arguably with the conditions under which it developed); 1988-90: telephone operator at a transport agency, 1990-96 bartender, 2002-2003 unemployed, etc.

Today, Sadr-Haghighian, 29 years of age, is a fake blonde of an impressive height of six feet one, who nonetheless dresses in mercilessly high heels. Sitting in her atelier in Santa Monica, I listen as she elaborates on the bioswop project, quoting Toni Negri, Gertrude Stein and Stéphane Mallarmé, but I cannot concentrate. I’m mesmerized by a black leather collier of metal studs gracing her left wrist, which impeccably complements the purple lighter with which she is lighting a fresh Marlboro, saying “HAVE A GREAT 98” in orange Serpentine font.

“See, it’s a question of whether you can mirror the oil crisis — which, to state the obvious, paralleled the crisis of the “object” in the arts — in present conditions of production.” I realize she hasn’t been talking about bioswop at all, but some project she did at the Kunstverein last summer.

I nod, trying to look sympathetic, and think back to the website explaining how Sadr-Haghighian had documented the oil crisis of ’73, staging a dialogue between two women standing on a German freeway, discussing the neo-Hegelian convictions of Henry Kissinger. She stubs out her cigarette, the filter lined with lipstick (Chanel Crushed Rose, unless I’m very mistaken), reaches for her handbag and starts furiously rummaging through its contents until she finds a DVD. “OK,” she mumbles, “this is where Kissinger and biography meet.”

After making us coffee, Sadr-Haghighian shows me the DVD, a short and unassuming video from 2003. Sure enough, it refers to biography from a more geopolitical angle, light-heartedly pointing out that, according to the copyright specifications for Adobe, and other software, it is against the law to export the programs to “rogue states” such as Cuba, Syria, Iran, Sudan, etc. — but also that any citizen of these countries is automatically barred from using them.

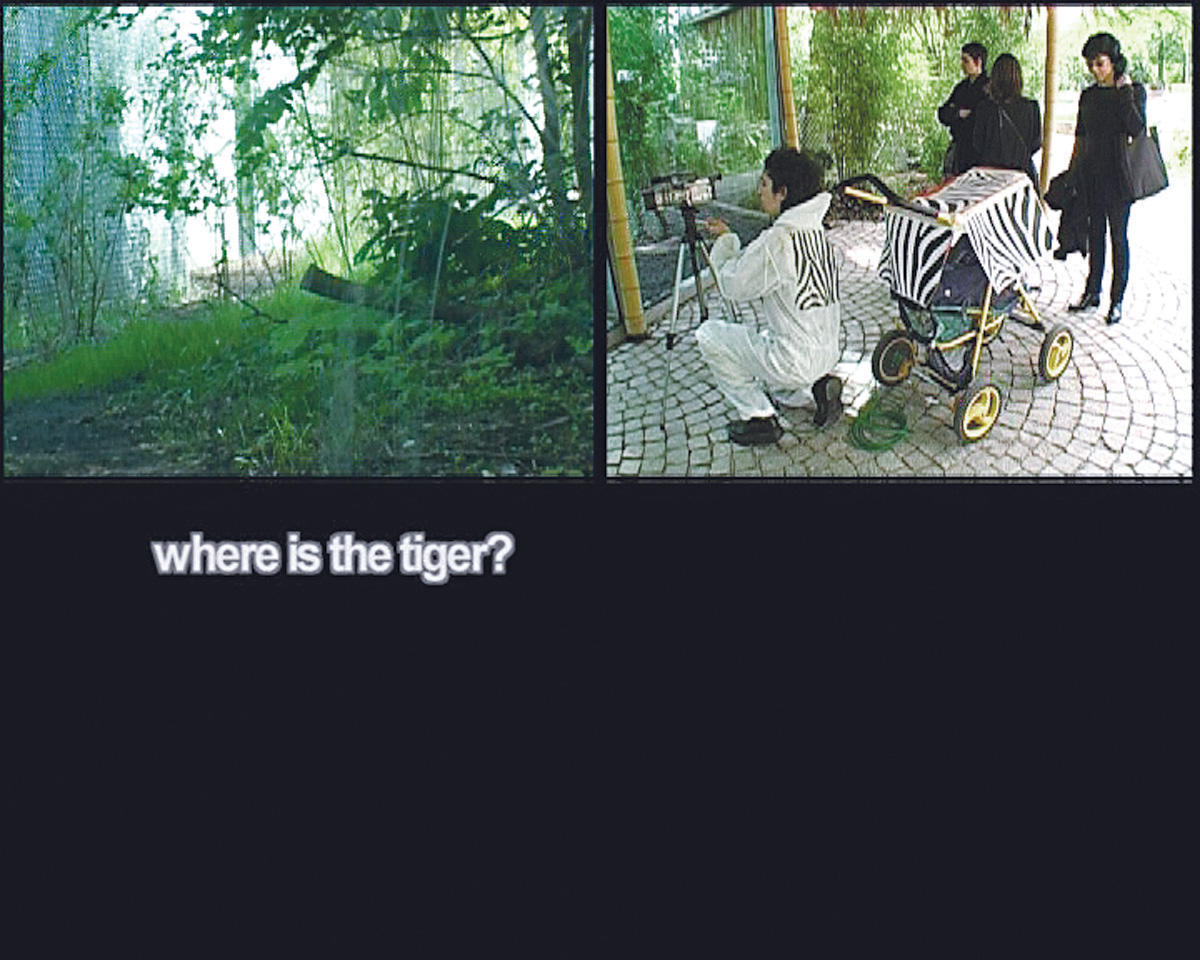

The first time I met Sadr-Haghighian, at the Istanbul Biennial 2001, she was presenting the video Present but not yet Active, (which is the dictionary definition of latency), a commentary on the 1999 Manifesta. Instead of accepting the invitation to the Manifesta, Sadr-Haghighian in turn invited the three curators to a visit to the famous Frankfurt zoo. The zoo in question is based on the theories of zoologist Bernard Grzimek, who began his illustrious career during a time of decolonization, when Africa and its wildlife resorts was being left to people he could not trust. Grzimek was very intent on modernizing the zoos in the West.

His suggestion was a new and more authentic mode of display, with painstaking reconstructions of the animals’ surroundings. The problem, of course, is that if you stick a tiger in dense jungle foliage, people can no longer see what they’ve just paid 10 Euros to see. Not only does this raise good questions regarding authenticity and visibility, the images, in Sadr-Haghighian’s film, of the three curators — hiding behind their shades as they wait by a Grzimekian jungle setting with Sadr-Haghighian, dressed in a zebra-striped camouflage outfit, standing by — are among the most gripping I’ve ever seen.

“So did you ever meet Grzimek?” She looks pained by my question, and frowns grimly out the window into the Santa Monica sunset. But then she smiles, and changes her mind. “Actually, I attended one of his workshops on spectator psychology. Harare, 1995. Such a charming man. A true gentleman in every sense of the word.” I have a feeling she’s mocking me. Not all of Sadr-Haghighian’s work so clearly hails from an artistic tradition of institutional critique, or sociopolitical reflection, at least not at first glance. Her practice is too engaged with convoluted questions of form and structure, of performance and ceremony, to be as predictable as so many political artists, and other compagnons de route.

A number of installations, such as Schnitte (Cuts, 1998), operating with little more than furtive slices of shadow, or Trigger (1999), a superposition occurring every two hours of two urban images shot in Munich, are inquiries that in many ways stick close to the mechanical medium of the slide projector, even as they probe into larger questions of representation. A third piece involving slide projectors, fast moving consumer goods (1999), uses images of three different types of spaces — abandoned spaces, artspaces, business offices. The more visitors walked into the gallery, the faster the slide projector was activated. The activity accelerated the change of images, making the piece a witty allegory of gentrification.

Through Sadr-Haghighian’s selection of particular visual elements, be they curators, biographies, or shadow slices, the chosen entities become decontextualized objects of observation and projection, and are “individualized, hooked to their new host — the system that they were chosen by,” she says, pensively pouring some Nutrasweet into her coffee.

“Its place within reality, its state of being becomes completely dependent on the evaluation and further observation by the system. Any method of creating an image of someone, or something, is ultimately a technique of isolation. It begins with pointing a spotlight at the object, which becomes brighter than its surroundings, more detailed, easier to observe. To be more sophisticated, you can exchange the spotlight with a camera, or a microscope, but the mechanism stays the same.”

“Same goes for an interview, right?” I ask, trying to sound suave and self-reflexive. She smiles a tired smile, obviously bored by the question. Punctuating the hushed silence of her studio, her studded wristcollar gleams and flickers in the fading auburn sunlight pouring through her windows. “So how tall are you exactly?”

She sighs. “Five foot ten.” I know she’s lying.