Liverpool

Documents from the Atlas Group Archive

FACT

November 2005–January 2006

Art from Lebanon hadn’t been on Liverpool’s cultural agenda for a while — eight years in fact, since artist Walid Sadek’s residency in the city — and then, like the proverbial British bus, two exhibitions came along together. In 1998 Sadek commented on the dilemma an artist from the Middle East, or indeed from anywhere, faces in trying to make art about either his current locus or about his homeland: the first option would necessarily be from the perspective of the tourist, while the second might further exoticize Beirut for a Liverpool audience. Doubting art’s capacity for transcendence, Sadek remarked that “the specificity of an art practice cannot be measured in opposition to Globalization’s ravenous mobility. Rather it should operate through the notion of the ‘local’ as an already co-opted terrain.” This problematic of the local — as a context for both art’s production and reception — provides a useful starting point for approaching the two exhibitions.

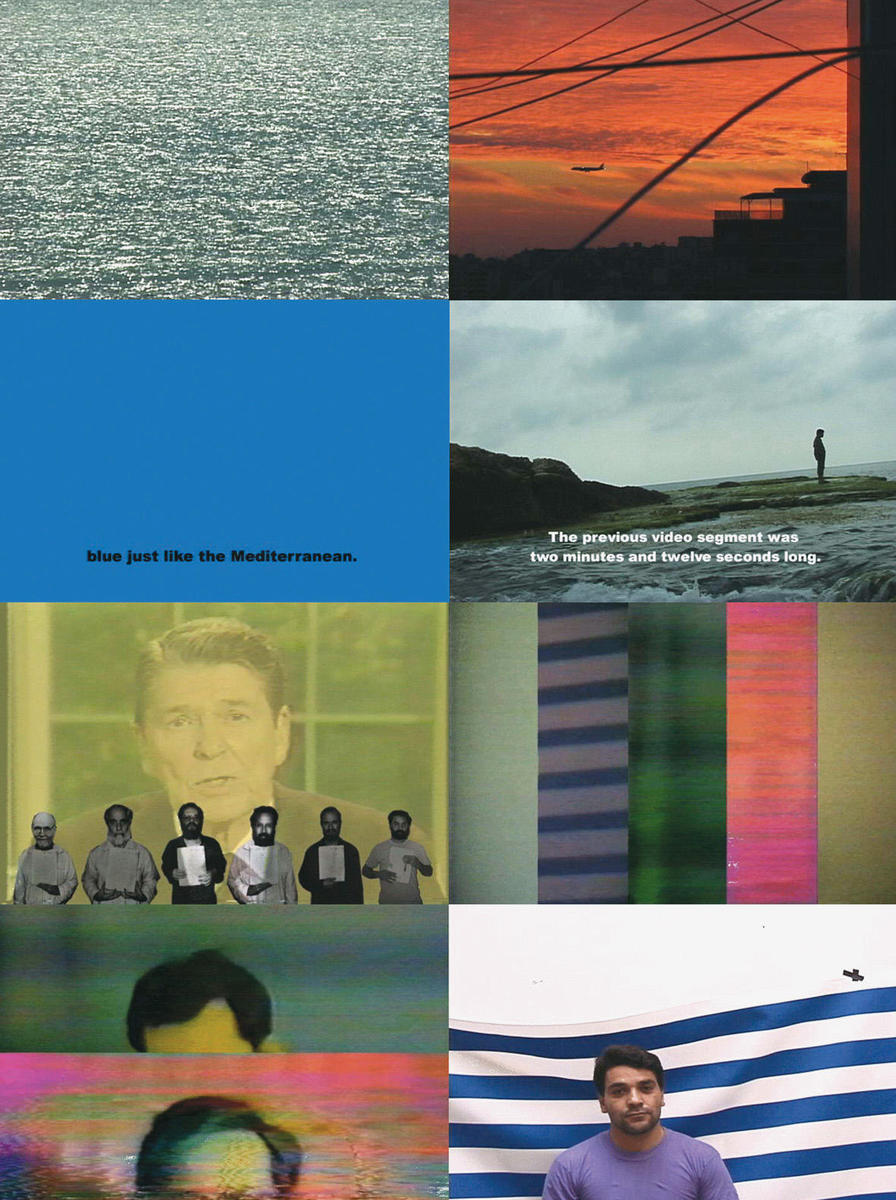

FACT presented a selection of familiar and more recent installations and videos from Walid Raad’s ongoing Atlas Group project, established in 1977 as “an imaginary foundation” to research and document Lebanon’s contemporary history. Ostensibly created from the memories — real or imagined — of Lebanon’s wars, and drawn from archives whose provenance and even existence is questionable, Raad’s claim on the terrain of the local is used as a critical device.

The powerful sculptural qualities of I was overcome with a momentary panic at the thought that I might be right (2005), go beyond the dubious background provided to the work’s conception — as a replica of a model supposedly made by a Lebanese army topographer to illustrate all detonations in Beirut between 1975 to 1991, each one represented by a circular hole cut into a large disc of high-density foam — to resemble a mysterious lunar landscape. One wonders if Raad was aware in presenting the Atlas Group in Liverpool of the local irony, even prescience, of using a Liverpudlian actor to provide the voice over to one of the videos in Hostage: The Bachar Tapes (2001). In this we hear the testimony of the only Arab to be taken hostage in Beirut together with a group of Americans in the 1980s. Recorded several years before a Liverpool man, Ken Bigley, was kidnapped in Iraq and subsequently killed, his plight the subject of intense media and public debate (not least about Liverpool’s capacity to wallow in sentiment), there is a poignancy that the actor’s Scouse accent, heard in this local context, brings to the work.

The thin line between fact and fiction referenced in the exhibition’s title could equally be the separation that exists between an elaborate joke and a profound meditation on what constitutes the authentic in our increasingly mediated reality. The extent to which technology invades and shapes our lives, not least through the new realities being wrought in the global language of television, is eloquently explored in this exhibition. The possibility that we might become seduced by the conceptual precision and formal seamlessness of Raad’s enterprise to the exclusion of the work’s overarching political punch is absent in ‘Beirut Out Of War’, an exhibition much rougher round the edges, though it is very much borne out of, rather than about, war.

The show was curated by Mai Ghoussoub, who invited three other Lebanese artists to respond to the reality of contemporary Beirut. Arriving at the top floor flat that is the welcoming if unlikely home of the Museum Man, it was easy to miss Rana Salam’s photo essay of daily life in the Lebanese capital, which was set out like a visitors’ book in the cramped lobby. An impressive procession of architectural arches constructed by Souheil Sleiman out of robust cardboard sheets ran the length of the hall, floor to ceiling. Similar to pit props erected in a mining tunnel to stave off collapse, the installation’s subterranean suggestion works to disorienting effect. It leads to Ghoussoub’s own installation, which similarly turned reality on its head. Fascinated by the decorative beauty of Beirut’s aging cast-iron manhole covers, which are being replaced by nondescript shiny red ones, the artist has photographed them and suspended the images from the ceiling; one was compelled to look up to see what is normally underfoot, or to observe their reflection in mirrors mounted on the floor. Rather than displaying nostalgia for a disappearing feature of the city’s fabric, Ghoussoub suggests that collective memories of a place torn apart by war are as likely to be found in the overlooked utilitarian remnants of the urban environment as in the familiar facades of buildings.

The most remarkable thing about Ara Azad’s paintings is that they arrived at the gallery in one piece. These brightly colored portraits on canvas had been dispatched from abroad by the artist without any protective packing, and the postage stamps and destination address in Liverpool were incorporated into the works — perhaps a comment on the resilience of the diasporic artist’s existence. Ghoussoub had also extended an open invitation to other artists to send postal works about global locations emerging from conflict. Among the responses, Marisa Rueda’s delicate pencil drawing of pious yet militaristic birds of prey was a potent reminder of the wounds inflicted by the junta in her native Argentina. It was appropriate, too, that the arts collective Visible had been invited to present their critique of the post-9/11 War on Terror, Disappeared in America, as part of the FACT show. By embracing other voices in different ways, both exhibitions effectively and generously opened up space to extend the scope of creative discourse from the focus on a specific, localized Middle Eastern history to a broader, critical engagement with the present.