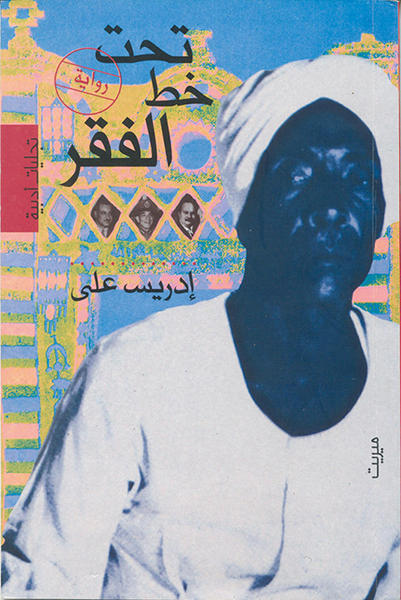

Taht khat al-faqr: riwayah

(Below the Poverty Line: A Novel)

By Idris Ali

Dar merit, 2005

Arabic

A group of ragged villagers in southern Egypt go to their local government official to complain about the flooding of their land, inundated as a result of the building of the monstrous Aswan Dams. The official, a smug Cairo bureaucrat, handily dismisses their objections, telling them that the land is not theirs, but Egypt’s. The villagers retort, “This is Nubian land.” “And what are you?” demands the official. “We’re Nubians,” they answer. The official disagrees. “No, you’re Egyptians, like I am,” he says. They counter, “If we were Egyptians, you wouldn’t have treated us this way.”

This fraught exchange between villagers and government official strikes at the heart of Idriss Ali’s latest novel, Taht khat al-faqr. Though an Egyptian citizen, Ali is foremost a Nubian writer, fiercely proud of his heritage. (Nubians primarily inhabit southern Egypt and northern Sudan; they are descendants of the ancient Nubians.) But if Ali is proud of his heritage, he’s also angry. His new novel is seething with rage, as it documents the travails of a young Nubian Egyptian whose family and village fall prey to poverty after the construction of the Aswan Dams.

The dams (the first, the Low Dam, was finished in 1902 and heightened twice over the next three decades; the second, the High Dam, was built during the 1960s) not only flooded the lands Nubians had been farming for thousands of years, but also led to the forced displacement of many Egyptian Nubians, a large number of whom ended up in Cairo as servants or menial workers. There they would often meet racism and discrimination because of their dark skin and unique cultural identity. As if that weren’t enough, the High Dam also deluged many monuments, artifacts, and archeological sites of ancient Nubia, thereby wiping out, in one fell swoop, a legacy of thousands of years of history, culture, and civilization.

It is against this background of disenfranchisement and displacement that Taht khat al-faqr takes place. The novel opens one afternoon in August 1994, with our protagonist wandering the streets of Cairo, driven by poverty and failure to plan the end of his life that very day. The story then skips back a few decades, to his childhood in a village in southern Egypt after the construction of the dams, chronicling his community’s descent into poverty. From there, it traces his trajectory as he attempts to escape the destitution of his village by fleeing to Cairo. Life in Cairo, however, is no easier. Unable to attend a proper school, forced to take whatever backbreaking work comes his way, at odds with his violent father, and prey to sexual predators, he finds himself trapped in an increasingly vicious cycle of deprivation.

As a testament to the racism that Nubians have suffered at the hands of Egyptians, and as an account of displacement, dispossession, and poverty, Ali’s novel succeeds. As a work of art, however, Taht khat al-faqr falls short of the beauty and form of some of his earlier fiction, particularly his marvelous novel Dongola: A Novel of Nubia. Its very title — Below the Poverty Line — evokes the heading of a standard UN or Oxfam report, and the book in fact often reads like a case study in urban poverty rather than a novel. There is little character development in the work; the first section of the book, a kind of stream of consciousness, runs a bit like a political tirade, so that the protagonist appears as a flimsy, one-dimensional mouthpiece for the author himself. Clearly Ali was venting his own feelings. But even if the novel is a disappointment in certain respects, it still bears traces of the author’s gifts as a writer. Moving seamlessly between standard Arabic and colloquial Egyptian, Ali’s language is at once stark and lyrical, simple and evocative.