Jordan

Oraib Toukan: Counting Memories

Darat al Funun

May 8–July 22, 2007

The act of remembering — that is, the act of trying to recall a thing past, and memory itself, namely, the mnemonic imprint and narrative of recalled events — seem to operate on slightly different planes, though they’re inextricably linked. In “Counting Memories,” Oraib Toukan investigated the tension between the process and residue of memory, a tension that exists especially when that memory, whether collective or individual, resists settling effortlessly into the annals of history.

Toukan insistently highlighted the fragility of memory and forgetfulness, tracing how they’re inscribed within a sociopolitical consciousness. The “body” of work here—all produced between 2006 and 2007 — brought memory back into the realm of the corporeal and the material, where it could be breathed, ingested, printed, and even written on the body. With the title “Counting Memories,” however, Toukan seemed to suggest that even if we could transform our memories into quantifiables and do away with their residual aura, we still could barely grasp a sense of truth.

The friction between meaningful amnesia and vacuous memory was enacted obsessively in the three video works Trying to count memories without laughter’s disruption (2006), Remind me to remember to forget (2006), and One donkey and three phrases (2007). Each of these works could be perceived as a momentary snapshot trying to contain history, a history burdened with the Sisyphean task of remembering itself ad infinitum until it could finally make sense.

All three works made strategic use of textual repetition, wherein phrases were written and rewritten at different paces and even in reverse. Past, present, and future blurred into each other, scrambling temporality and rendering time indefinite. This was especially vivid in the looped three-channel video installation One donkey and three phrases, three mirrored boxes each showing footage of a donkey munching away at the phrases “I perceived a past,” “I remembered a present,” and “I witnessed a future.” Standing a few feet away, the audience saw the one image of the donkey eating the phrase, yet a closer look inside the box showed the kaleidoscopic diffraction of the image, splintering the time-space continuum. Whereas a linear reading of each phrase carried a particular historical weight and momentum, the multiplication of the mirrored images contested that. We were invited to be voyeurs to the prism of history.

Memory inscribed on the body was the subject of the series of photographs Man with tattoo (2007). Four photographs depicted a man’s back with a large tattoo comprised of a hand holding a dagger in the shape of Palestine, a pair of eagle wings in the Palestinian national colors, and the Palestinian flag. The word “Palestine” was written in Arabic vertically on the man’s spine, as if subtitling the tattoo and underlining the significance of its symbolism. National pride, the desire for a Palestinian homeland, and a resistance to occupation were literally grafted onto the skin, transforming it into a live site commemorating the situation of the Palestinian people. This plight was a collective one, as emphasized by the anonymity of the photograph’s subject: he was faceless. As the series of photographs progressed, dark shadows fell over the man’s body, obscuring his arms, clipping the wings of the tattoo, so that eventually the only thing we could discern was a tiny Palestinian flag floating in a black void. Functioning as a trope for fading memory and the forgetfulness of the world regarding the Palestinian trauma, the series also correlated the gradual disembodiment and dismemberment of its subject to the gradual territorial loss of Palestinian land.

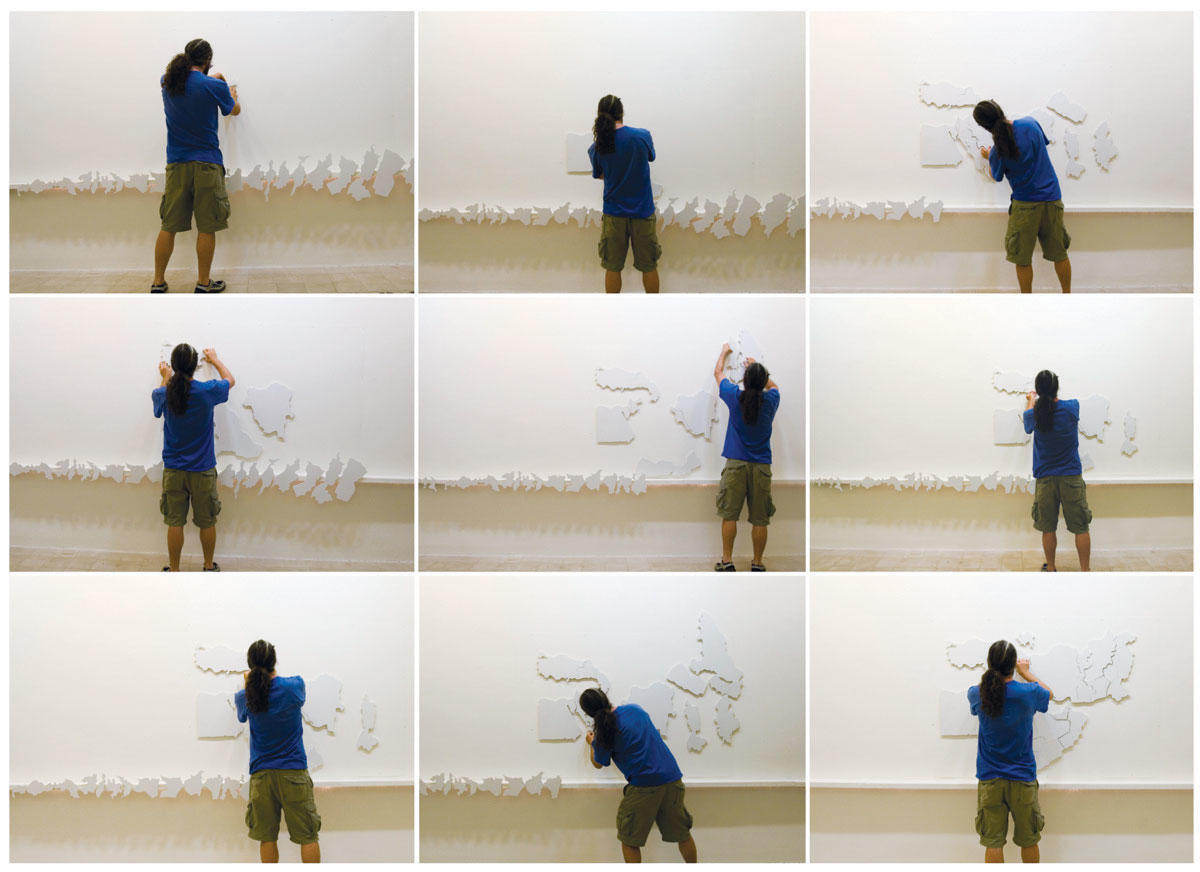

In The New(er) Middle East, Toukan offered a wry and playful critique in the form of an interactive puzzle in which viewers could reorganize the map of the current Middle East. We reshuffled our maps with humor and lightness, since our moves appeared to be inconsequential, yet with every gesture we created an alternative vision and geopolitical blueprint of the Middle East, which in reality remains umbilically linked to its political history. The installation reminded viewers that the topography of our decisions is never innocent, just as no map is ever neutral.

Far less playful and much more solemn, if not monumental, in tone was the installation Good Morning Beirut (2006), which viscerally evoked how history repeats itself. For many who lived through the experience of the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, the 2006 Israeli war on Lebanon conjured up painful memories and imagery.

Here, Toukan simultaneously chronicled the mediation of war (she collected the personal email she received during the first few weeks of the war) and re-mediated what she’d archived, reprinting the messages on a paper roll, fixing the communication in time and preventing its redistribution. In other words, it was as if Toukan wanted to capture the residual memory of 1982 and its 2006 iteration and solidify it in the hope that history might not repeat itself again but instead find closure. For the version at Darat al Funun, almost a year after the war, she grossly exaggerated the paper roll, making it impossible for viewers to consult further messages, and draped its pages across the floor and wall, making the text at times illegible, begging a “reading between the lines” at multiple levels. The aesthetics and the object value of the installation have changed as time has progressed. The object-document of her private correspondence has become part of the public domain, as a sculptural memorial that finds its strength in unwritten pages and histories. The seemingly infinite roll of paper that Toukan lay before us hinted that many rooms and walls still need to be draped if we want to catch a glimpse of the lived experience of war.