The Colonel

By Mahmoud Dowlatabadi

Translated from Farsi by Tom Patterdale

Melville House, 2012

In 2006, I was asked to address an audience in Tehran on the novels of Orhan Pamuk. He had been the recipient of that year’s Nobel Prize for Literature, an award that his detractors in Turkey denounced as being tainted with politics. There was also unease among my audience in Tehran — for reasons of national pride. Many Iranians regard Turkey’s written culture as inferior to their own. Some of my listeners that evening resisted the idea that Pamuk’s qualities as a writer might somehow have qualified him for the prize. “Why,” asked one man, hinting at conspiracy, “has the Nobel Committee never honored an Iranian writer? What has Pamuk got that Dowlatabadi hasn’t?”

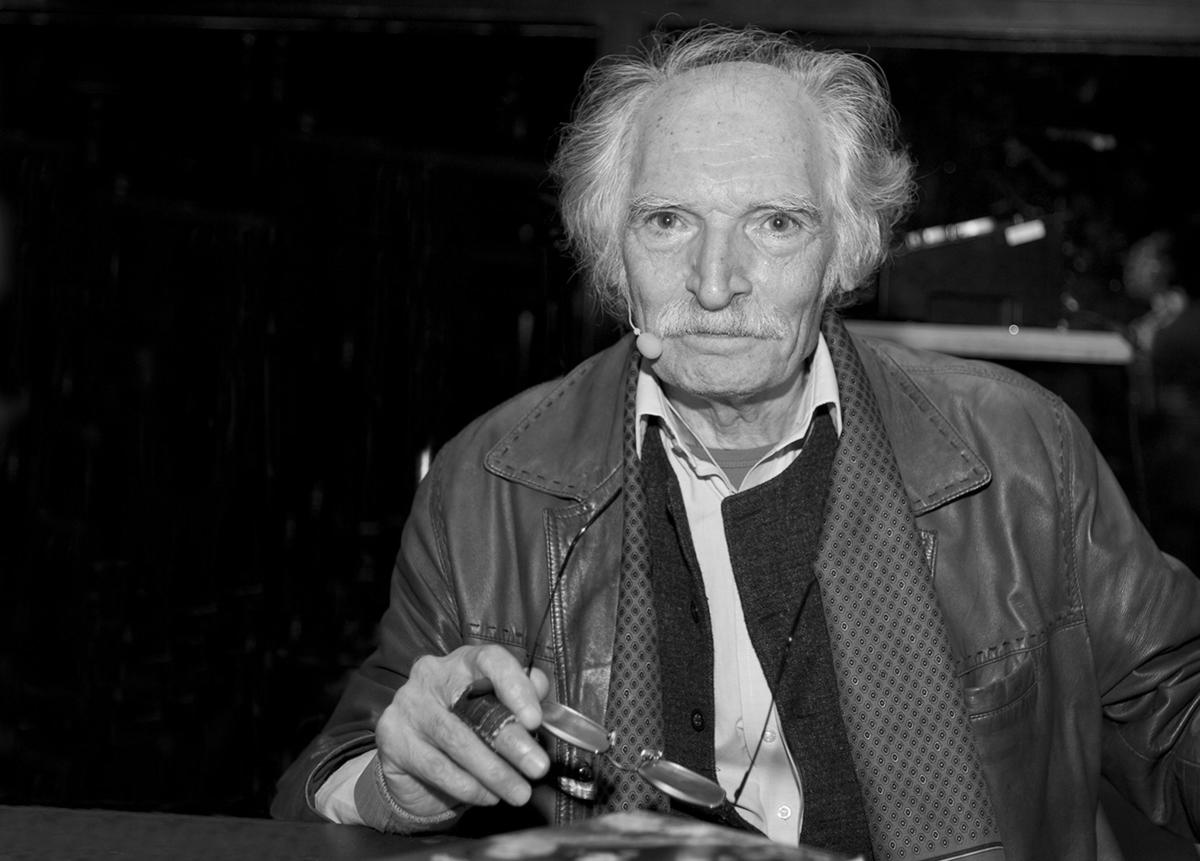

With his domed pate, knotted brows and mustaches heavy with foreboding, Mahmoud Dowlatabadi is the instantly recognizable dean of Iranian novelists. His vast oeuvre — his longest book, Kelidar, is three thousand pages long — aims to restate in poetic terms the agonies of Iran’s modern history. He has been a pioneer in the use of vernacular language in his books, and has consistently shined a penetrating light on the suffering of the marginalized, rural poor in his more than half-century of writing. Despite refusing to emigrate or to remain silent — the lot of many other creative souls — he has survived.

For all that, as the man at my Pamuk talk implied, Dowlatabadi is curiously underappreciated. The conditions under which he works partly explain this. Iran’s politics, recent history, and cultural temperature militate strongly against literary output of any kind. The book-buying public is small; there is censorship, capriciously applied; financial returns are a joke. In an interview in 2008 with the BBC’s Persian service, Dowlatabadi advised his fellow novelists to set aside all hopes of worldly reward. The novelist’s life, he said, is one of “pure idealism.”

In the same interview, Dowlatabadi spoke bitterly of the near-silence that had greeted another of his big novels, The Vanished Lives of the Old, published in installments a couple of decades ago. “Fifteen years — the time of a child’s life until adolescence — I spent on this book, and I waited two or three years for the permit to publish it, and even then it was as if nothing had happened. What is this place? A bog? A swamp? I put my maturity as a writer into this book. And I’m sure I acquitted myself well enough. Where’s the result?”

Dowlatabadi’s perspectives as a writer are too deliberately cramped and his characters too ethereal for him to be called a historical novelist. But his new book, The Colonel, nonetheless gives imaginative shape to one of the seminal events of the last century, the Islamic Revolution of 1979. Dowlatabadi started his career writing for the stage in the turbulent mid-1970s (when he himself was jailed for his activism), and one can imagine The Colonel being dramatized — with its dramatically highlighted central figure, the eponymous colonel, soliloquizing mordantly amid the ruins of his family life.

Dowlatabadi directs all the violence of revolution onto a single family, starting with the corpse of the colonel’s counterrevolutionary daughter, whose laborious burial forms the main action, and going on to two more children, one killed during the uprising that toppled the Shah, the other at the front in the Iran-Iraq war. Just two offspring survive: Amir, a leftist who has been released from prison and leads a troglodyte existence in his father’s basement; and a girl, Farzaneh, who is protected by her opportunistic husband, an Iranian vicar of Bray. Death first touched the colonel when he killed his adulterous wife years before. By the end of the novel, it will consume him, too. No particle of humor lightens Dowlatabadi’s depiction of the totalitarian nightmare. The tone is phantasmagorical, reminiscent of the father of the modern Iranian novel, Sadegh Hedayat. Putrefaction and obscenity reflect the moral malaise; no one is exempt. A familiar archetype, the secret policeman, haunts the family home in a rainswept provincial town, parasitical, by turns domineering and wheedling, adopting the cause of whoever happens to be in power. All this is well rendered in Tom Patterdale’s sensible translation.

The Colonel is also a funeral for history — from which lessons might be drawn, and “what if’s” asked. Revolutions like a tabula rasa, so, at the end of the book, in the colonel’s fevered mind, there is a show trial of honest patriots who tried to reform Iran. Among the defendants is Muhammad Mossadegh, who nationalized the oil industry in 1951 and was overthrown in a coup organized by the CIA and MI6, and an earlier modernizing prime minister, Amir Kabir, murdered by the autocratic Nasser El Din Shah in 1852.

The colonel feels closest to his namesake, Colonel Muhammad-Taqi Pesyan, whose portrait he has kept for the past half-century, and whose combination of culture and political will seemed briefly, in 1921, to offer an alternative to absolutism. (In the event, Pesyan was killed at the behest of his political enemies). The verdict of the trial is, of course, foregone. One by one, Iran’s finest sons are sentenced to death.

In The Colonel, Dowlatabadi has left an important memorial to the early years of the revolution — and, perhaps, another clue as to why he himself is more respected than loved. “Whatever we might or might not have done,” the colonel’s son Amir observes, “the end result is that we are all to blame.” The bleakness of this vision pervades The Colonel. Some readers may yearn for signs of redemption.

Dowlatabadi’s book is unlikely to be the subject of much debate in the land of its birth. Rarely has the revolution been so brutally dissected by an artist working in Iran. Publication there seems a distant prospect. As the translator notes, “the manuscript remains in the hands of the censor, who has demanded a number of deletions and revisions, which the author has refused to make.”