“Capitalize on random snippets of sound.”

—The Homosexuals

“The Family of Noise is here and it’s come to save everybody.”

—Adam Ant

“We’re in tune with disoriental philosophy.”

—Charles Gocher, Sun City Girls

Alan Bishop doesn’t care if you like him. When a major British music magazine complained that Bishop’s band, the Sun City Girls, “presents mocking images of the Other,” Bishop went off on the “academic clowns” and “anal-retentive warlords of the keyboard” who take exception to the group’s promiscuous approach to sound-making. On scores of limited-edition or out-of-print recordings, over the course of their twenty-five-year career, the Sun City Girls have fused rock and jazz and a world’s worth of differently tonal music to produce one of the great American avant-garde legacies.

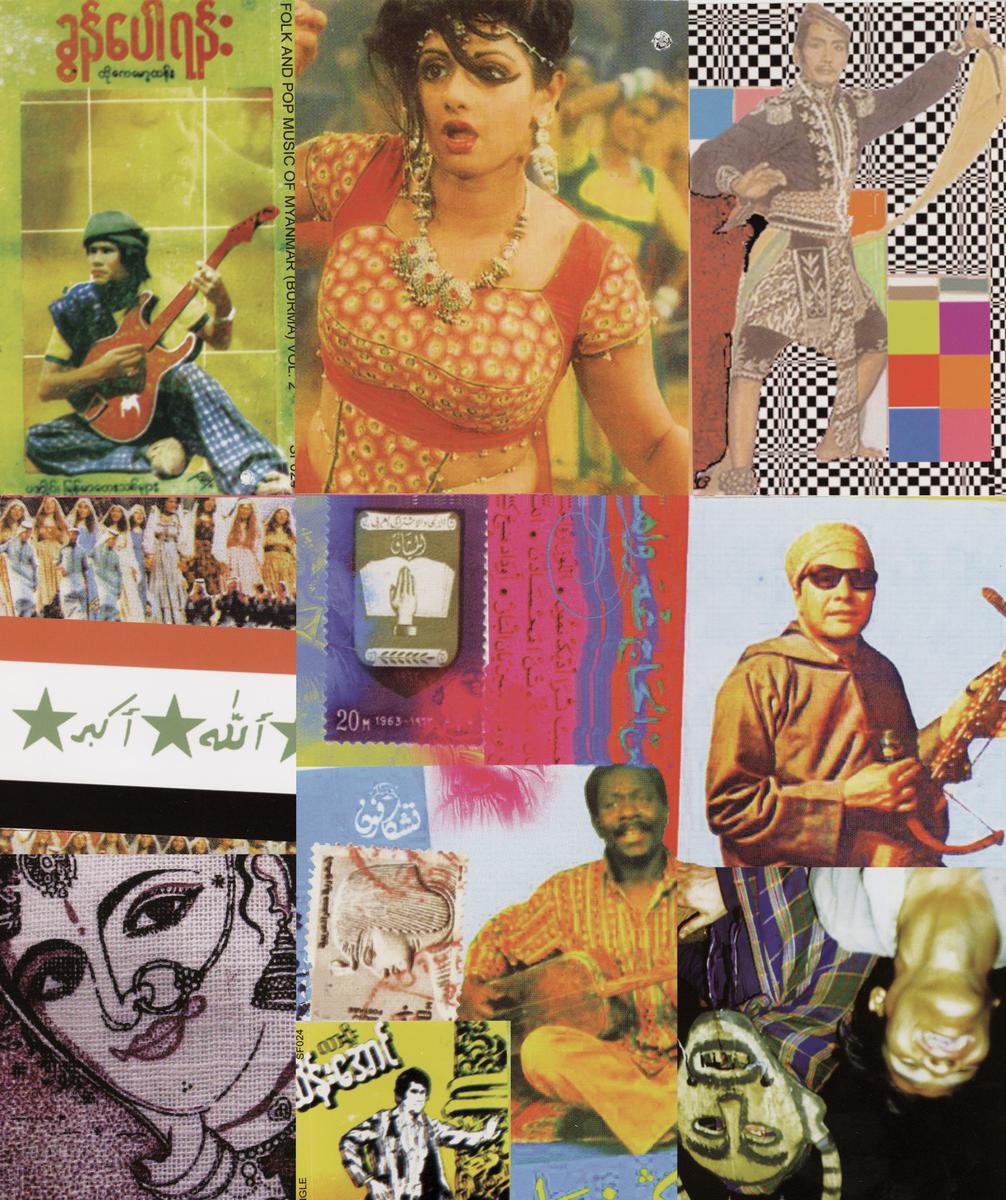

Or maybe two, as Bishop is also the founder of Sublime Frequencies, a loose-limbed collective of Seattle-based ethnographers-without-portfolio. SF has been releasing CDs and DVDs of recordings from some of the world’s less-traveled pop and folkways music since 2003. Choubi Choubi: Folk and Pop Sounds From Iraq and Radio Pyongyang: Commie Funk and Agit Pop from the Hermit Kingdom, for example, document the curious destiny of popular music along the axis of evil. They’re emblematic, as well, in that the sublime radios seem to seek out stations in the Middle and Far East, with occasional dips into North Africa. To the untrained ear — my own, for example — the end result is a sometimes boring but often intoxicating carnival of sounds, splashed and shadowed with ungraspable meanings.

Not surprisingly, many of these sounds have long been part of the Sun City Girls’ psychedelic assemblage. Many of the SF releases were actually recorded a decade or more earlier, during travels in Africa and Asia (including Burma, where Bishop met his wife); listening to them provides an intriguingly skewed perspective on pivotal 1990s SCG recordings such as Torch of the Mystics or 330,003 Cross Dressers From Beyond the Rig Veda. SCG records feature all manner of wordless chants, filtered tones, fake accents, and melodies in borrowed and made-up languages. Sometimes the song titles provide coordinates: “Apna Desh,” “Space Prophet Dogon,” “Esoterica Abyssiania.” Sometimes they don’t: “Archaeopteryx in the Slammer,” “I Knew a Jew Named Frankenstein.” Sometimes the material blends together, as with “Cruel and Thin,” an atmospheric and moving serenade that turns out to be a cover of a song taped off of Moroccan radio.

Not that we know anything about the original — the singer, the name of the song, the year of its recording, etc. This is one of the most controversial things about most SF releases: songs go unnamed, bands go uncredited (and, by the transitive property, unpaid); liner notes are brief or non-existent. “It doesn’t have to be funded,” Bishop says. “You don’t have to go to school to learn how to record or to learn how to interpret a foreign culture or bring it back and spin it for someone. You don’t need to have 500 microphones; you don’t need to gather up these people for recording sessions and pay them 1000 dollars apiece. As far as I’m concerned, it’s open season, and you record what you want to record. It’s disappearing, too. It’s good to get it while you can.”

That last sentiment, of course, is the self-justification for nearly every act of ethnographic appropriation. As Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart notes in his compelling book Songcatchers, a diverse crew of documentarians, ranging from Alan Lomax to Bela Bartok to Mickey Hart himself, spent much of the twentieth century going out to capture the rawest, most authentic songs they could find, whether in Mississippi or Papua New Guinea or the Hungarian countryside. The SF crew, by contrast, go out to capture the rawest, most fucked up songs they can find, including the kinds of hybridized turbo-folk that Bartok dismissed as “gypsy slop.”

And whereas most “songcatchers” today go to great lengths to demonstrate that they, in Hart’s words, “understand that music belongs to the people who make it,” the SF crew are equally interested in the idea that music belongs to the people who hear it. Bishop called Radio India “an encyclopedia without an index.” Hisham Mayet calls his documentaries “interpretations of situations put together in a subjective order.” Many of the SF releases are experimental artworks themselves: mosaics of “field recordings” of radio broadcasts, in which songs or bits of songs are spotted with white noise and advertisements and shock-jock DJ patter. On Radio Thailand or Radio Java, you’re listening to someone listening, spinning the dial, recording at will. Bishop refers to the collages he’s done with the Sun City Girls as “personal talismans,” and one comes away from much of the Sublime Frequencies catalogue with the same feeling.

Listeners may find it difficult to be angry with SF; for musicians, it’s not such a stretch. Jayce Clayton, a writer and DJ who has worked extensively with Moroccan musicians, was shocked to find well-known songs by well-known bands presented as mysterious tokens of Arab genius on Radio Morocco. (One person’s sublimity is another person’s livelihood.) One of those bands, Nass El Ghiwane, was a pioneering, genre-bending, psychedelic jam-rock band (not unlike the Sun City Girls themselves). There is a sense in which Nass El Ghiwane seem like secret sharers in the whole SF enterprise: in Hisham Mayet’s forthcoming film, Trans-Saharan Musical Brotherhoods, one of the most mind-blowing performances features the audience singing, dancing, and swaying along as a cover band pounds its way through an old Nass El Ghiwane song. Viewers of the film, however, or at least of the cut I saw, learn nothing about the song, its performers, or its authors (save for the not unimportant fact that they are fucking awesome).

Critics of the SF modus operandi have a way of getting under Bishop’s skin. Complain about a lack of context or compensation, and he’ll attempt to smother you with a surrealistic pillow, denouncing “hipster progressives… squirming on the rump of an epileptic unicorn, attempting to decipher which buttons to push to claim their fifteen minutes of fame.” What Bishop and company desperately want to preserve about this music is the experience of mystery. The sound-images they produce are the opposite of mocking; what they reveal is a kind of longing.

It’s hard not to find a clue to the defensiveness in the biographies of the SF crew. Alan Bishop and his brother Richard, half-Lebanese, grew up in Flint, Michigan, down the street from their grandfather, an oud player whose house served as a kind of meeting place for musicians, businessmen, and Freemasons (often the same people). Mark Gergis, whose releases include the amazing two-disc set I Remember Syria and a collection of Cambodian pop culled from moldering cassettes at the Oakland Public Library, Asian Branch, is a half-Iraqi American from Detroit. All three have talked about the formative experience of feeling embedded in something they couldn’t quite comprehend; of not quite understanding their mothers’ native tongues; of growing up in the shadow of something magical and foreign. It’s an old and storied predicament, being torn between two worlds, and it has many possible outcomes. For the SF crew, one answer is to safeguard that essentially mysterious experience of intimate connection — in the case of the Sun City Girls, to recreate that experience by singing in languages not only foreign but nonexistent, to insist on the privacy of experiences — like hearing music at shows — that are also public. Many of the best songs and collages made by the group acquire an extra poignancy precisely by dint of their obscurity. Like a lullaby for the lost.

That deliberate obscurity is lovely in its way, but it is not necessary. The Libyan-born filmmaker Hisham Mayet’s work here is instructive. My favorite of his SF projects, Niger: Magic and Ecstasy in the Sahel, set out to capture a spirit possession ritual and other instances of “pure folklore.” It’s easy to quibble with the liner notes, but it’s impossible not to marvel at the hot Pentecostal funk Mayet managed to capture on film, the captivating drone of Group Inerane (the Toureg Velvet Underground?), and the awesome spectacle of remote people acting totally normal in front of a camera-shy and awkward and graceful and weird.

In any case, if SF’s latest releases are any indication, forced mysticism may be on its way out. Omar Souleyman: Highway to Hassake and Group Doueh: Guitar Music From the Western Sahara are direct collaborations with musicians. There’s still plenty of room here for epiphany, but there’s less in-your-face otherworldliness. (There are still no translations of lyrics provided, however, so for those of us who don’t speak Arabic or Tamasheq, the voices we hear will be mere instruments.) A few more moves like this could defang even the “squirmiest” of hipster progressives. Perhaps a compendium of Nass El Ghiwane covers?