Let’s recap. Globalization — this obscure word remains consistently used and misused. Today, anything which includes non-western nationalities/cultures/ethnic or political groupings is defined as being the face of this globalization. On the art front this globalization is rampant; inIVA (London) produces the hit show The Veil; the Fridericianum (Kassel) opts for In the Gorges of the Balkans prepping the art market for the art of the new European states; in the aftermath of September 11, Witte de With (Rotterdam), the Bildmuseet (Umeå) and Fundació Antoni Tàpies (Barcelona) co-host Contemporary Arab Representations; and PS 1 (New York) introduces us to poverty and violence in Mexico City: An Exhibition about the Exchange Rates of Bodies and Values. In this so-called new age of multi-culti/fusion/hybrid everything, globalization rhetoric is not only modish but economically viable as well — a catchphrase for a product line.

In the coming paragraphs, I don’t want to redundantly propose yet another definition of globalization (in 1998 alone, 2822 academic papers on globalization were written and 589 books on the subject were published), but rather I will try to put forward a suggestion of the three most commonly utilized understandings of this term and how they manifest themselves in the culture trade.

Definition One: For the economically-minded, the World Bank explains, “Globalization is the growing integration of economies and societies around the world.” From this definition comes a plethora of theoretical texts and sociopolitical analysis ranging from the hyper-objective writings of Saskia Sassen to the highly reductive statistics of Naomi Klein. Massive amounts of social science and economic research are continuously produced, of which most responsible cultural practitioners are somewhat informed. Art critics, culture theorists and curators make use of this research and incorporate it in their analysis of exhibitions, art works and practices, biennales, and so on and so forth. (See Authentic/Ex-centric [Venice], Unpacking Europe [Rotterdam/Berlin], Unrealized Democracy: Documenta 11 [Kassel], When Latitudes Become Forms: Art in a Global Age [Minneapolis], and the like.)

Definition Two: Globalization is a process that is gnawing away at authenticity, destroying cultures which must be preserved. Here we have the goodwill factor, wherein promoters of cultural exchange discuss preservation in a spirit fueled by a contrived romanticism. In accordance with their position, an affirmative action culture is advocated. Workshops, networks, collaborations are the way to get to know each other, to learn and develop — more often than not the result is condescension in the guise of generosity; cultural-specificity and the local are stagnant prescriptions — difference is celebrated as long as it is maintained. Cultural parasites are the most active under this banner; certainly coming soon, we’ll have Baghdad Blues: Art in a Post-Saddam Iraq curated by whoever got there first.

Definition Three: Any interaction across cultures/borders/ethnic groups constitutes globalization, from elephants parked outside McDonalds in Bangkok and German businessmen drinking Corona to the mysterious all-powerful internet. This view is the outcome of the infectious “other” rhetoric systemically dominating today’s political arena. In this case, McDonald’s is perceived as the original global messenger — ignoring that, McD’s revenues aside, many historical transnational cultural sources like the Bible are still more popular than a Big Mac. Fortunately most exhibitions and projects produced in this language are easily forgotten, although the impact of their underlying assumptions is alarming.

Various combinations of these definitions are constantly at play, and when the word pops up, everyone gives a politically correct nod to indicate that “yes, we are all on board here” — we know that exploiting Malaysian workers is bad but the spread of wonderful Ethiopian restaurants is great, and of course finding a balance is so very complicated. And once again, complex issues are reduced to generic mis/understandings to minimize damage and keep latent conflicts at bay. We are not in the politics industry after all; this is just about art.

“Art cannot change the world” are words spoken nonchalantly day in and day out, and the agency of the arts and culture production industry is comfortably reduced to the mere fetishism of a few privileged practitioners. Discussions of the seminal role of funding agendas, curatorial policies both of private and public institutions, production values, etcetera, are simply engulfed by the standardization machinery. And for those not so easy to appease, well they can chat, complain and theorize about “representation,” and there is funding for that too. And of course, the machinery of standardization also provides the margins for this debate: post-colonialism, exoticism, Orientalism, regionalism and so on.

But how does this globalization hype impact professional practice on an individual level? I am a Muslim, Arab female. Whatever implies tragic inflictions in the real world puts me at great advantage on a politically correct cultural stage eager to flaunt its openness. Professional integrity can only be maintained somewhere in the equilibrium between exploitation and self-serving, reckless opportunism; and to find the balance, one must suffer the curse of acute self-consciousness, a condition which can incite bouts of paralysis — or conversely – might inspire the occasional original thought. How can one situate/frame one’s self either locally or internationally on one’s own terms? Isn’t participation in the representation debate a legitimization thereof? And under what conditions can new paradigms emerge?

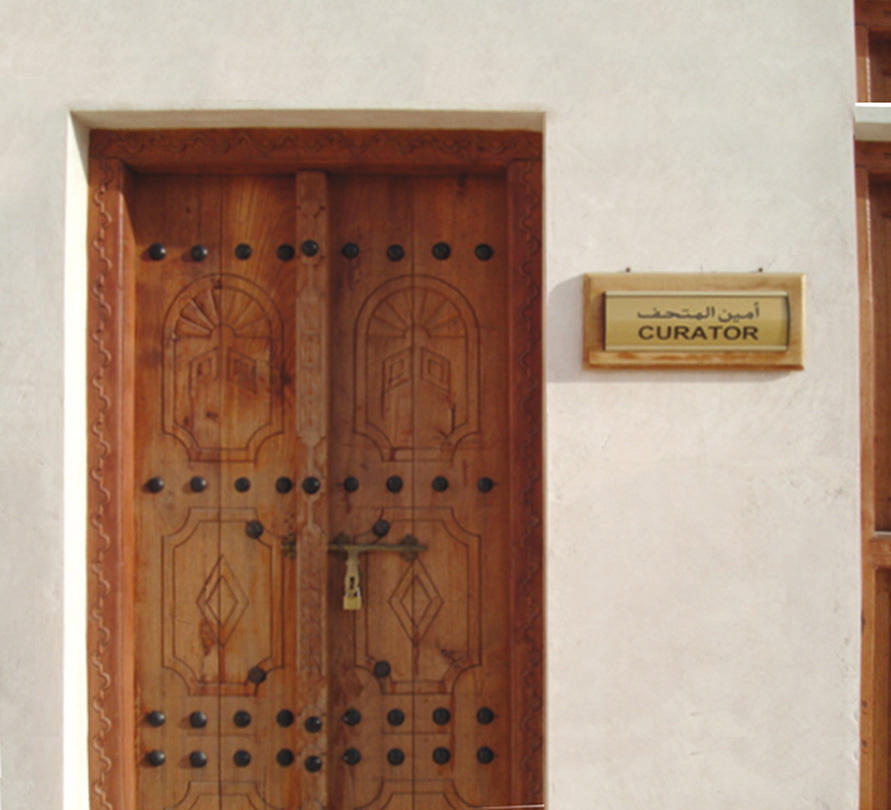

On the local level, the dynamics are different. In Egypt and perhaps the Middle East at large, this luxurious separation of art and politics does not exist. Official instruments and propaganda are the original purveyors of the Bush-esque dictum: “If you are not with us, you are against us!” In this atmosphere, independent curatorship is involuntarily a form of cultural activism mixed with a zeal for art, some administrative skills and a hint of academic savoir-faire that allows for making small talk with the history of twentieth century western art. Contextualization remains the name of the game; but without locally-generated artistic references and sources, where is the backbone of a more inclusive and shared discourse? On what grounds do you build local art critical debates? No wonder the art works easily fall prey to superimposed categorization on the international scene — they keep traveling without any luggage!

The question on everybody’s mind remains: What curatorial strategies work amidst these conditions? What are the criteria for evaluating whether or not a curatorial strategy works anyway?